YUAN ART

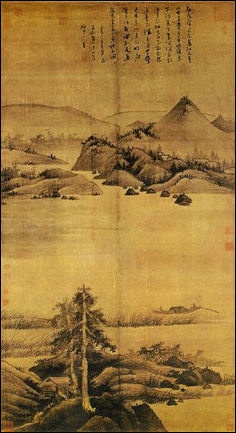

Fisherman by Wu Zhen

According to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art: “The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) was founded by Kublai Khan (1215–1294) who moved the capital from Khara Khorum in Mongolia to Dadu (modern Beijing) in China. This transference brought about a shift in focus as Kublai sought to strike a balance between traditional Mongol customs and Chinese culture. For example, although the Mongols practiced shamanism (in which a shaman mediates between humans and the spirit world), they maintained an open policy toward religion. Kublai restored Confucian ritual at the court and supported his mother’s Nestorian Christian sect, while he and his successors favored Buddhism. Muslims also attained positions of power and wealth under the Yuan. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

“As rulers of China and in accordance with a more sedentary lifestyle, the Mongols constructed buildings and patronized art. Kublai erected a magnificent marble palace in his summer capital Shangdu (Xanadu), celebrated in Marco Polo’s account (“the halls and rooms and passages are all gilded and wonderfully painted…”). The Mongol’s sponsorship of art and international trade—both largely a matter of self-interest—helped to propel Chinese forms, motifs, and techniques westward to Iran, where they contributed to the formation of a new visual language.” ^\^

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Many of the techniques used in arts and crafts during the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties were established in the previous Yuan dynasty under the Mongols. For example, designs painted in underglaze blue and underglaze red rose in the Yuan dynasty and flourished in the Hung-wu, Yung-lo, and Hsuan-te reigns of the following Ming dynasty. The import of "Tadjik ware" from the Middle East greatly influenced the aesthetics of cloisonne enamelware in the Hsuan-te and Ching-t'ai reigns. Chinese lacquer ware was renowned in foreign lands during the Yuan dynasty and inspired the famed carved lacquer wares produced in the Yung-lo reign. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

“The culture of the Mongols is characterized by its multi-faceted, pluralistic features. Gold works, Buddhist sculptures, ritual objects and certain patterns on ceramics exhibition all reveal a strong affinity to Tibet and Islam. That porcelains of some of the major kilns of China have been discovered in Inner Mongolia serves to confirm that trade between the north and south was common during the Mongol Empire and Yuan Dynasty. \=/

Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; GENGHIS KHAN AND THE MONGOLS factsanddetails.com; YUAN (MONGOL) DYNASTY (1215-1368) AND THE MONGOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; YUAN DYNASTY CULTURE, THEATER AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; YUAN CRAFTS AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com; KUBLAI KHAN AND CHINA'S YUAN DYNASTY (1215-1368) factsanddetails.com; MARCO POLO'S DESCRIPTIONS OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; YUAN-MONGOL INVASIONS OF BURMA, JAVA AND VIETNAM factsanddetails.com; MARCO POLO AND KUBLAI KHAN factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty” by James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com; “Housing, Clothing, Cooking, from Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion 1250-1276" by Jacques Gernet Amazon.com ;“The Urban Life of the Yuan Dynasty” by Shi Weimin, Liao Jing, Zhou Hui Amazon.com; “Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com ; “The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties” by Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368" by Herbert Franke and Denis C. Twitchett Amazon.com; Painting: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Masterpieces of Chinese Painting 700-1900" by Hongxing Zhang Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Yuan Art and the Scholar-Official Class

Kyujozu

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Yuan dynasty was a period of diverse ethnic groups co-existing in China. Officials divided people in China into four major categories: Mongols, Central Asians, Chinese, and Southern Chinese. Cultural and social interaction between them became quite common, and exchange often took place in the form of relations based on marriage, studies, and government office. The Mongol Yuan dynasty is thus distinguished by an unprecedented multiethnic group of scholar-officials. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

Works of painting and calligraphy by literati of different ethnic backgrounds are on display in this section. They reflect the unique scholar-official environment of the Yuan dynasty and the new manner in art that it fostered. In the early Yuan dynasty (mid-13th century), some scholars of the former Sung dynasty, such as Cheng Ssu-hsiao (1241-1318) and Ch'ien Hsuan (ca. 1235-before 1307), rejected the Yuan and expressed their grief and longing through writing, painting, and calligraphy. Other Chinese literati, however, accepted the call to service by the Mongol government, and they included the influential Chao Meng-fu (1254-1322) and Hsien-yu Shu (1256-1301). Through their advocation of revivalism in art, they helped to give life to ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy in this new era. \=/

“By the middle Yuan (early 14th century), literary gatherings and the practice of presenting and inscribing works of painting and calligraphy reached a peak among both Chinese and non-Chinese groups. For example, Ts'ao Chih-po (1272-1355) did "Mountain Peaks Covered in Snow" for the Tibetan Hsi-ying (A-li-mu-pa-la) and Chao Yung (1289-ca. 1360) did "Five Horses" for the Central Asian scholar Pei-yen-hu-tu. Through the support of foreign scholars and officials in China, traditional painting and calligraphy reached a diverse audience as its influence became widespread. Many non-Chinese artists joined ranks, including Kuan Yun-shih (1286-1324), K'ang-li Nao-nao (1295-1345), Sa Tu-la (ca. 1300-ca. 1350), Yu Ch'ueh (1303-1358), and Po-yen Pu-hua (Bayan Buga tegin, ?-1359). Using traditional art forms of the Chinese, they created a new approach in painting and calligraphy that was both unadorned and straightforward. \=/

“By the late Yuan (mid-14th century), however, civil order disintegrated and the path to office became closed for scholars. They did what was necessary to survive in these times of trouble, and reclusion became an increasingly viable and popular choice among scholars. Needless to say, exchange between ethnic groups was curtailed considerably. Consequently, scholars such as Huang Kung-wang (1269-1354), Wu Chen (1280-1354), Ni Tsan (1301-1374), and Wang Meng (ca. 1308-1385) used painting to express the ideal of seclusion to a select group of friends. The result was that the Yuan dynasty became the defining period in Chinese literati painting and had a profound effect on later generations of scholar-artists.” \=/

Mongol Symbols in Chinese Art

Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ In the creation of luxury textiles and objects for the Mongol elite, Chinese artists developed a visual language that was an effective means of establishing their rule and consolidating their presence throughout the vast empire. A number of motifs that were part of the existing artistic repertoire were adopted as imperial symbols of power and dominance—the dragon and the phoenix, for example, two mythical beasts that integrated the ideas of cosmic force, earthly strength, superior wisdom, and eternal life. The Mongol versions of the creatures are the highly decorative sinuous dragon with legs, horns, and beard and the large bird with a spectacular feathered tail floating in the air. In Iran, these motifs were often paired and became so popular with the Ilkhanids that they eventually lost their original meaning, becoming part of the common artistic repertoire in the first half of the fourteenth century. [Source: Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee, Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Other motifs of this period that were familiar throughout the Asian continent are the peony, the lotus flower, and the lyrical image of the recumbent deer, or djeiran, gazing at the moon. The flowers, often seen in combination and viewed from both the side and top, provided ideal patterns for textiles and for filling dense backgrounds on all kinds of portable objects. The djeiran became widespread in the decorative arts because of the well-established association of similar quadrupeds with hunting scenes."^/

Goosehunt

“For the semi-nomadic Mongols, portable textiles and clothing were the best means of demonstrating their acquired wealth and power, so it is reasonable to assume that the main mode of transmission of motifs such as the dragon and peony was through luxury textiles. The most prominent clothing accessories were belts of precious metal (gold belt plaques, The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art). Many of the textiles illustrated here prove transmission from east to west, yet in some instances, exemplified by the Chinese silk with addorsed griffins (cloth of gold: winged lions and griffins, The Cleveland Museum of Art), the origin of the image is clearly Central or western Asia. The Mongol period is unique in art history because it permitted the cross-fertilization of artistic motifs via the movement of craftsmen and artists throughout a politically unified continent."^/

Yuan Painting and Calligraphy

Painting, compared to other art forms, remained relatively free from alien influence, with the exception of the craft painting for the temples, and reached a very high level. Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The Song and Yuan periods are considered by many the high point of painting in China.” During the Yuan Dynasty painters worked at capturing their own feelings and ideas and the qualities of their ink and brush rather than qualities of their subjects. Scholar artists were the leading figures in the arts, and their painting were characterized by simplicity, understatement and transcendent elegance.

The most famous painters of the Yuan era were Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), a relative of the deposed imperial family of the Song dynasty, and Ni Zan (1301-1374). According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Painting: The art of painting also flourished under Mongol rule. One of the greatest painters of the Yuan Dynasty, Zhao Mengfu, received a court position from Kublai Khan, and along with Zhao's wife Guan Daosheng, who was also a painter, Zhao received much support and encouragement from the Mongols. Kublai was also a patron to many other Chinese painters (Liu Guandao was another), as well as artisans working in ceramics and fine textiles. In fact, the status of artisans in China was generally improved during the Mongols' reign. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Mongols originally did not have a tradition of painting and calligraphy. With the establishment of the Golden Clan in China proper, however, the Mongols adopted the custom of collecting and connoisseurship in painting and calligraphy — their collection seals serve as testimony to a new form of high culture. For example, Huang T'ing-chien's calligraphy "Poem on the Hall of Pines and Wind" and Liu Sung-nien's painting "Lohan", both from the previous conquered Sung dynasty, bear the ranking princess' prominent seal "Huang-mei t'u-shu". "Early Snow on the River" by the Five Dynasties painter Chao Kan and the Sung dynasty "Ting-wu Rubbing of the Lan-t'ing Preface" also bear the impression of Emperor Wen-tsung's seal "T'ien-li chih pao". Furthermore, "Hsiao-i Stealing the Lan-t'ing Preface" by the Five Dynasties artist Chu-jan bears the seal of Emperor Hsun-ti that reads "Hsuan-wen ko pao".Through collecting, connoisseurship, and impressing seals, the Golden Clan expressed a new form of refined cultivation in China. Furthermore, officials of various ethnic backgrounds mingled and wrote inscriptions at imperial elegant gatherings and the imperial library, thereby creating a new court culture. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Primordial Chaos by Zhu Derun

Yuan Dynasty paintings in collection at National Palace Museum, Taipei include: 1) "Kublai Khan Hunting" by Liu Kuan-tao; 2) "Meeting Friends in a Pavilion Among Pines" by Wang Yuan. Works of calligraphy from the same period in the museum include: "Regulated Verse in Seven Characters" by Chang Yu.

Styles and Themes in Yuan Painting

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Hunting was one of the most important activities of traditional Mongol steppe culture. In Yuan dynasty paintings, the appearance of hunting activities not only increased dramatically, but animal subjects also became quite popular. Horses were an especially important, and hawks and falcons (often used on the hunt) appeared more often. For example, "Falcon" was originally considered a Sung dynasty (960-1279) painting, but the style suggests a late Yuan dynasty date and the inscriptions were all done by late Yuan scholars. In their writing, they praised the hunting abilities of the falcon, which also served as a metaphor for success and heroism in human society. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

“"Auspicious Grain" represents exceptionally tall rice plants with each stalk bearing two ears of rice, symbolizing a particularly abundant harvest. Documentation refers to the rice plants in "Auspicious Grain" as having a unique habitat allowing all the "grains to come together", referring to unification of many different ethnic groups in China under one emperor. Indeed, the tall and dense rice stalks here indeed suggest abundance through unity. The dark color of the rice not only indicates imminent harvest, but also serves as a metaphor for imperial unity of China and ethnic harmony. The simple and straightforward style of this work complements the direct visual presentation of the subject. Traditional brush mannerisms have been reduced to a minimum, reflecting an innovation in painting style for the time. \=/

“"Ruled-line" painting refers to a detailed style using a ruler for depicting buildings and other structures, and it was favored by the Mongol Yuan leaders. Their interest in structures may be related to their patronage of temple and palace construction in the capital of Ta-tu (present-day Peking). Representative ruled-line paintings include Wang Chen-p'eng's "A Dragon Boat Regatta" and Li Jung-chin's "A Han Dynasty Palace". Both reveal a sense of opulence that does not depend on beautiful colors. Rather, the great variation in ink tones and brushstrokes reflects to an even greater degree the artists' consummate skill. Furthermore, precise inkwork in monochrome bamboo paintings, such as Li K'an's "Bamboo of Peace Through the Year", also became popular in the Yuan dynasty.” \=/

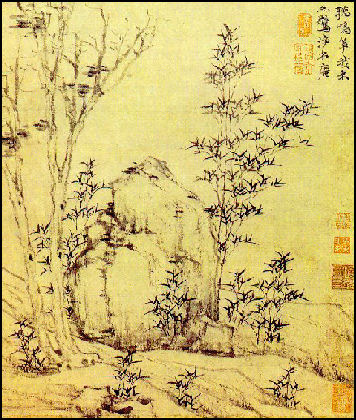

by Zhao Mengu

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Yuan dynasty was the first time in Chinese history that the entire land was ruled by non-native ethnic groups. Some Chinese subjects from the previous Sung dynasty refused to accept this new reality and expressed in their painting and calligraphy a form of nostalgia for the old days. Ch'ien Hsuan (ca. 1235-1307) is a typical example. A Sung civil service candidate, he came to enjoy the elegant life of upper-class society in the Southern Sung capital of Hangchow. With the destruction of the Sung by the Mongols, however, he burned his Confucian robes and his writings, and he settled in Wu-hsing (Zhejiang province) as a professional painter. On the surface, the subject of his "Autumn Melons" has auspicious undertones — the buyer of the painter wishing for many descendants (just as a melon has many seeds). However, Ch'ien's poem on the work contains a reference to growing melons by the Marquis of Jang, a famous recluse in the Eastern Han period (25-220). Thus, behind the fine and attractive style lies a scholar-artist "left over" from the Sung who rejects the new dynasty in favor of the ideals of reclusion and antiquity. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Yuan Dynasty: A Transitional Time in Chinese Painting

According to the Shanghai Museum:“The Yuan dynasty is an important transitional period in the history of Chinese painting. In the early Yuan period, Zhao Mengfu, Gao Kegong, as representatives of the scholar-official painters, rejected the Art Academy style to continue the tradition of the Tang and Northern Song dynasties. By advocating the use of calligraphic traits in painting, they ushered in the Yuan style characterized by its unique mood and freedom from conventions. In the middle and late Yuan, the literati Xieyi paintings became the prevailing trend. These used the subject of paintings to express the feelings of the artist. Plum blossoms, orchids, bamboo and rocks were the symbols of a lofty and strong personality while isolated mountains and rivers symbolized passive and reclusive feelings. The ‘Four Masters of Yuan’ shaped the stylistic traits of the literati landscapes. Flower-and-bird painting continued the style of realistic representations with heavy colors and developed a style of clear ink and wash technique, similar to line drawings. This fresh, delicate style was the forerunner of the late Xieyi ink flower-and-bird painting. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ Although Chinese literati ultimately learned how to live with Mongol rule and many members of the educated class cooperated in continuing government along the "Confucian" lines of the traditional Imperial state, many members of the elite were alienated from the government, and sought ways to avoid service. In effect, this freed a substantial number of educated men — many exam graduates from the late Song — from burdens of government responsibilities. A certain number of these men turned for fulfillment to artistic achievement, and it was the portion of these who devoted themselves to painting who truly established a tradition of literati visual art. Lacking the type of technical training that had characterized earlier academic painters, the Yuan literati applied their control of brushwork, derived from calligraphy, to the development of a new perspective on what art could achieve. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

In a handscroll by the Yuan artist Zhao Mengfu the effort at "verisimilitude" (making things look realistic) has completely vanished. Mountains, trees, and grass are now rendered very simplistically, without any real care for relative size. Even more, the sky is now covered with writing (the red seals of ownership were added later by collectors, including some self-important emperors). The interest has shifted from the landscape to the painter — it's his act of reinterpretation of nature which is now the focus. This is a fundamental shift and it is central to literati painting. This enormous region of Chinese landscape art is not devoted to Nature — it is devoted to man's response to Nature. Nature — and painting — has become a means for expressing the artist's unique self and perspective. Although this is a very Neo-Daoist idea, most literati artists "Confucianized" it by laying emphasis on the notion that the aspect of the self that was expressed also reflected one's moral self-cultivation and stance towards society. /+/

Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters

Autumn Wind by Ni Zan

The Four Masters of the Yuan dynasty were Huang Gongwang (1269-1354), Wu Zhen (1280–1354), Ni Zan (1306-1374), and Wang Meng (1308 – 1385). They were active during the Yuan dynasty but given their designation in the Ming dynasty, during which and after they were deeply revered as promulgates the “literati” tradition of painting”, which valued individual expression and learning over outward representation and immediate visual appeal. [Source: Wikipedia]

Huang Gongwang and Wu Zhen belonged to the early generation of artists in the Yuan period. They consciously emulated the work of ancient masters, especially the pioneering artists of the Five Dynasties period, such as Dong Yuan and Juran, who rendered landscape in a broad, almost Impressionistic manner, with coarse brushstrokes and wet ink washes. The two younger Yuan masters, Ni Zan and Wang Meng respected by the the work of their predecessors their styles were very different as well as different from each other. Ni Zan's style has been called "restrained thinness" while Wang Meng is known for his "embroidered richness". The work of the Four Masters encouraged experimentation and the use of novel brushstroke techniques.

Wu Zhen (style name Zhongkui; sobriquets Meihua daoren, Meishami) was a native of Weitang within Jiaxing, Zhejiang. He was good at poetry, cursive script, and painting landscapes, bamboo and rocks, and ink flowers. In landscape painting, he followed the Five Dynasties artist Juran and and, in ink bamboo, Wen Tong of the Song dynasty,absorbing the styles of previous masters to establish his own personal manner and creating marvelous works to become one of the Four Yuan Masters.

Wang Meng, a native of Wu-hsing (modern Hu-chou, Zhejiang), was a grandson of the famous artist Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322). he also was taught by Huang Gongwang while learning from such figures as Ni Zan. He also stood on his own, becoming one of the Four Yuan Masters. In the early Ming, Wang Meng was implicated in the case of Hu Wei-yung and subsequently died in prison. His painting followed the styles of Wang Wei (701-761), Tung Yuan (fl. 1st half of 10th century), and Chu-jan (10th century), and he established a style of his own, becoming one of the Four Great Masters of the Yuan along with Huang Kung-wang (1269-1354), Wu Chen (1280-1354), and Ni Zan (1301-1374). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Even though he wasn't one of the Four Yuan Masters, Zhou Mengfu was perhaps the greatest painter in the Yuan Dynasty. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ In the Yuan dynasty Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters highlighted the spirit harmony and a new sense of brush and ink in their works, firmly establishing literati painting as one of the unwavering stalwarts of Chinese art. Zhao Mengfu, a member of the Sung imperial clan, resided in Wu-hsing, Zhejiang. His style name was Tzu-ang, and his sobriquet was Sung-hsueh tao-jen. In the following Yuan dynasty, he also served as a scholar in the Han-lin Academy, and was enfeoffed as Duke of Wei. His poetry and prose are pure and lofty, while his great achievements in calligraphy and painting have served as models for generations., He was famed as a revivalist in painting, which he often did with a calligraphic touch. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The tradition begun by men like Zhao Mengfu was enlarged through the rest of the Yuan Dynasty, and a number of exemplary literati painters developed simple but distinctive styles that were so admired that they came to be regarded as models for later painters (much the way that earlier, exemplary calligraphers had been models for later men). Great literati painters of the next 500 years would begin by adapting their calligraphic skills to the styles of these Yuan models of visual art as they learned how to paint. Settling on one or more as their primary models, they then would, if they were men of talent, develop original ways to enlarge on or depart from those styles, in paintings that were essentially new innovations, though always firmly within traditions of the past. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The goal of literati painters in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), including Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters (Huang Kung-wang, Wu Chen, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng), was in part to revive the antiquity of the Tang and Northern Song as a starting point for personal expression. This variation on revivalism transformed these old "melodies" into new and personal tunes, some of which gradually developed into important traditions of their own in the Ming and Qing dynasties. As in poetry and calligraphy, the focus on personal cultivation became an integral part of expression in painting.

Ni Zan

Ni Zan (1301-1374) is a great painter who lived in the turbulent shift from the Yuan to the Ming Dynasty. He was sometimes on the run and lived on a houseboat to elude tax collectors. About 50 of his paintings remain today. New York Times art critic Holland Carter wrote, "No artist more distinctively transformed landscape into a state of mind...His paintings are houseboat-size: small, neat as a pin images of slender trees...set against immaculate expanses of water and sky...He's a 'personality' painter of the most engaging kind (cranky, melancholic, funny)." Wang Meng was a contemporary of Ni Zan. He was accused of treason and died in a Ming prison. "The febrile tuning-fork quiver that his work sets up vibrates...sometimes amplified to a volcanic pitch." He "piled up mountains creased with deep, soft folds that resemble a beast on the throes of a convulsion.”

Ni Zan (style name Yuanzhen, sobriquets Yunlin and Yuweng), a native of Wuxi in Jiangsu, came from a wealthy family and had built the Qingbi Pavilion, amassing a collection of ancient painting and calligraphy. He excelled at landscapes and was the most austere of the Yuan masters. His paintings have spare ink style and empty landscape. On his hanging scrolls he dramatically reduced the ink and detail compared to the hanging scrolls of the Northern Song masters. Dr. Eno wrote: How little ink Ni Zan uses to create a hauntingly chill landscape! Beneath Ni Zan's work is a section from a handscroll by Wu Zhen, a hermit-artist who often celebrated lone fishermen in his work. Wu Zhen painted in several basic styles, using a dry brush sometimes, one wet with ink other times, but always creating scenes that conveyed the attraction of Nature, usually with only one or two isolated people lodged within it. /+/

Patricia Buckley Ebrey wrote: Ni Zan, stripped down his technique to all but the most essential brushstrokes. “Still Streams and Winter Pines” by Ni Zan was painted 1366, just two years before the fall of the Yuan dynasty, this painting represents the villa of a relative of the painter, Wang Meng (ca. 1309-1385). His inscription of a poem, by contrast to the painting itself, is rather lengthy. In it he states that he did the painting as a present for a friend leaving to take up an official post, to remind him of the joys of peaceful retirement. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“Zizhi Mountain Studio” by Ni Zan is an ink on paper hanging scroll, measuring 80.5 x 34.8 centimeters. “In this monochrome ink painting is a riverbank, scattered trees, bamboo, and a small pavilion. On the opposite bank, rounded mountains rise to form a composition simple and pure with a sense of expansiveness. The ink is light and elegant, a slanted brush used to render the outlines of rocks and mountains to create a sense of force and weight. The brushwork for the bamboo is especially powerful, making this a masterpiece by Ni. Though undated, the style here suggests a late work from around the age of 70.

Yuan Landscape Painting

Forest Grotto by Wang Meng

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “During the Yuan period, after the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty, many of the leading landscape painters were literati who did not serve in office, either because offices were not as widely available as they had been under the Song, or because they did not want to serve the conquerors. Scholars' landscapes, like the paintings they did of other subjects, were designed for a restricted audience of like-minded individuals. It was not uncommon for scholars to use the allusive side of paintings to make political statements, especially statements of political protest.[Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“It became quite common among literati artists of the Yuan to allude to earlier painting styles in their paintings. They were creating, in a sense, art historical art, as their paintings did not refer only to landscapes, but also to the large body of earlier paintings that their contemporaries collected and critiqued. Another trait of Yuan literati landscapists is that they did not hide the process of their painting, but rather allowed the traces of their brushes to be visible, going considerably further in this direction than painters of the Song. Wang Meng (ca. 1308-1385), the painter of Orchid Chamber, is one of the best-known Yuan landscape painters.

The Yuan court did not commission as many narrative paintings as the Southern Song court had, but the tradition continued. Yuan narrative painting may have appealed to the Mongol rulers not just for its story, but also for its depiction of animal combat. Horses were a popular subject for painters supported by the Khans. Gong Kai (1222-1307?), the painter of “Emaciated Horse”, was an extreme loyalist, who had held a minor post under the Song but lived in extreme poverty after the Mongol conquest, supporting his family by occasionally selling paintings or exchanging them for food. A slightly later painter, Ren Renfa, agreed to serve the Yuan court and even painted on official command, making him not that different from a court painter. /=\

Landscape Paintings by Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters

“Thatched Pavilion Under Rustling Pines” is a painting by Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322).According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The shapes of the pines and mountain forms all derive from those of the Li Cheng and Guo Xi tradition. The peaks were first outlined and then textured. Ochre was applied as a base for the coloring, to which blue and green were added. This complementary color scheme of warm and bright hues creates an archaic elegance that brings out the majestic silence and antiquity of the land. Sound is created by the suggestion of a breeze whispering through the pines. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Sparse Trees and Elegant Rock: by Zhao Mengfu is an ink on paper album leaf, measuring 54.1 x 28.3 centimeters. The painting depicts new bamboo growing near a rock beside three old trees. The rock was painted with a single brushstroke; the twisting and turning of the brush being accomplished with great skill. Dilute ink used for the texturing, providing a broad visual concept. The beautiful yet strong strokes for the branches reveal the force of the brushwork, being light as clouds with a calm manner.

“Bamboo and Rock” by Wu Zhen (1280-1354) is an ink on paper hanging scroll, measuring 90.6 x 42.5 centimeters. This work by Wu Zhen at the age of 68 by Chinese reckoning depicts a rock and two stalks of bamboo. Though using little ink, he attained a masterful spirit unsurpassed by a more complex composition. With refinement and skill, the brush flowed naturally in free variations. The famous Tang dynasty poet Du Fu once wrote, "Read a thousand books and the brush becomes divine," echoing the sentiment here.

“River Scene on a Spring Dawn” by Wu Zhen is an ink and light colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 114.7 x 100.6 centimeters. In his landscapes, Wu Zhen was much influenced by the tenth-century master Juran. "Hemp fiber" texture strokes define the mountain rocks here using strong and vigorous brushwork. The washes are done mostly in pale ink, lending a pure and elegant lightness to the work. Wu also employed a coarse brush to depict the trees, buildings, and figures. Though the strokes do not overlap, the results are quite satisfying. Perhaps this is a painting style that has "more than meets the eye," giving this work a commanding presence.,

“Fishing in Reclusion on an Autumn River” by Wu Zhen is an ink on silk hanging scroll, measuring 189.1 x 88.5 centimeters. “In this painting, a waterfall plummets between the layers of a precipitous cliff. Houses in a village are scattered amongst thick trees and rocky slopes, while in the far distance stretches an expanse of water, where a small, solitary fishing boat is adrift. A centered worn brush was used throughout the work, the artist combining forceful texturing with thick layers of semi-translucent ink washes to render the cliff. The sturdy pine trees also add a sense of strength and solidity.

Landscape Paintings by Wang Meng

“Thatched Cottage in Autumn Mountains” by Wang Meng (1308-1385) is an ink and light colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 123.3 x 54.8 centimeters. “This work from 1343 depicts the banks of a river, where reeds grow and a boat drifts. Trees intersect and in the fore- and middleground are buildings with ridges going up and into the distance. The piling of mountains and waters creates a dense and complex composition, the tangled texture strokes expressing the lushness of forests and land. The light and elegant brush and ink with exceptionally refined colors give bright clarity to the archaic heaviness, making this a masterpiece of Wang Meng's painting.

“Fishing in Reclusion on a Flowering River” by Wang Meng is an ink and light colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 124.1 x 56.7 centimeters. “A total of three works in the National Palace Museum, Taipei collection go by the title of this painting, with scholarship pointing to the one with the seal "Treasure Imperially Viewed by Jiaqing" as the finest. This is the one with the seal "Treasure Imperially Viewed by Qianlong" and has a poem inscribed by the Qianlong Emperor dated to 1754, the brushwork being slightly lower in quality. The work depicts river scenery with gently rolling slopes. Judging from the artist's inscribed poetry, this work appears to depict scenery on the Zha River. Buildings and peach trees appear hidden here and there, suggesting imagery of the Peach Blossom Spring.

“Forest Chamber Grotto at Chu-ch'u” by Wang Meng (1308-1385) is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 68.7 x 42.5 centimeters. This painting represents the scenery around the Forest Chamber Grotto at Lake T'ai. The fascinating grotto, layers of twisting landscape forms, dense trees, scattered buildings, and waves fill the surface of the painting, presenting a bold interpretation that goes beyond the appearance of the natural scenery. The composition is so dense that it appears almost claustrophobic. However, Wang Meng cleverly manipulated the areas of form and void to create a visual passage in the upper right corner. Thus, the view extends into the background and opens the composition to prevent a closed atmosphere. Wang used "ox-tail" texture strokes to delineate the landscape forms and long "hemp-fiber" strokes for the tree trunks. Combined with the dense "moss" dots, the brushwork is notable for its variety and finesse. Layers of ink washes were also added to create a distinction between light and dark. Finally, Wang Meng used touches of ochre and red to provide this painting with an aura of autumn.

"Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains" by Huang Gongwang

“Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” by Huang Gongwang (1269-1354) is one of the most famous Chinese paintings. Regarded as a masterpiece, it is one of the few surviving works by the painter Huang Gongwang, one the "Four Great Yuan Masters”. He spent his last years in the Fuchun Mountains near Hangzhou and completed this long handscroll in 1350. Rendered in black ink on paper, it vividly depicts the beautiful landscape on the banks of Fuchun River, with its mountains, trees, clouds and villages. Unfortunately, the painting was damaged by fire and split into two pieces in 1650. The first piece, 51.4 centimeters long and 31.8 centimeters wide, is kept in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou. The second piece, 636.9 centimeters long and 33 centimeters wide, is kept in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. [Source: Xu Lin, China.org.cn, November 8, 2011]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “''Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains'' is not only the greatest surviving masterpiece by Huang Gongwang, it is also a work renowned in the history of Chinese painting. The style of this handscroll traces back to Dong Yuan and Juran of the Five Dynasties and more recently to Huang's contemporary, Zhao Mengfu. It reflects the development of infusing calligraphic techniques into painting and the spirit of literati art with an emphasis on expressing ideas and freehand brushwork to create a new realm of monochrome ink painting. It also came to influence landscape painting of the Ming and Qing dynasties, having crucial value for drawing from the past and inspiring future generations in the tradition of Chinese literati painting [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw].

''Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains'' by Huang Gongwang

''Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains'' was completed in the equivalent of 1350, when Huang Gongwang was 82 years old by Chinese reckoning. Huang Gongwang(style name Zijiu, sobriquet Dachi) was born in 1269 during the late Southern Song in Changshu, Jiangsu. Of humble origins, he struggled to achieve an education, extensively studying traditional subjects to complement his numerous talents. In his youth he came to serve as a clerk handling documents in the Jiang-Zhe Branch Secretariat and by his middle years was even recommended for service in the capital. However, he became implicated in a case and was sentenced to prison. After serving time, he abandoned further thought of attaining official rank and returned to home, becoming a Taoist by profession and also developing his art of painting. At that time he often traveled around Suzhou, Hangzhou, Songjiang, and Fuchun, taking in sights from his travels and transforming them into landscapes of the mind, with paintings such as ''Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains'' having a major impact on later generations. Huang Gongwang died around 1354 and was buried in his hometown, having reached the Chinese age of 86.

“Huang Gongwang did not begin painting until around the age of fifty, though it is said that a text records him as being involved in painting in his early years. Not a painter by profession, he left behind few works. “''Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains,'' done by Huang Gongwang between the ages of 80 and 82, depicts the landscape in the area around the Fuchun River where he was traveling and residing. From right to left, the scroll follows the riverbank as hills and mountains rise and fall repeatedly with lush and dense trees. The scenery is sometimes deep and remote and at other times clear and expansive. The scroll throughout is rendered in a ''sketching-ideas'' type of freehand brushwork using monochrome ink. The application of the brush is quite calligraphic, at times gentle and serene, while at others free and untrammeled. The ink tones are rich and varied in the texturing and washes, tracing back to the simple and innocent style of Dong Yuan and Juran in the Five Dynasties and inspiring a tradition of literati painting in the following Ming and Qing dynasties. Other famous works by Huang Gongwang include “Search for the Tao” and “Autumn Clouds in Layered Mountains”

Yuan Figure and Landscape Painting

“Strumming the Zither Under Trees” is by Zhu Derun (1294-1365), a native of Henan province, who excelled at landscape and figure painting. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Shown in this painting is a group of three scholars sitting under a cluster of trees along the shore. One of them is strumming the zither as a fisherman in a skiff seems to paddle closer in order to listen to the music. An attendant at the stream’s edge turns his head and gazes back at the scholars. The composition is centered around these figures under the massive trees. A diagonal line of birds in flight echoes the angle of the shore extending into the distance, where the roof of a building emerges from the mist. The mist-drenched scene extends even further, evoking the sense of a pure and elegant atmosphere. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Lofty Scholars in the Shade of Pines”, attributed to Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 208 x 84.7 centimeters. This painting depicts a pure stream flowing among rocks with tall pines shading a slope. Two scholars sit there on mats, one playing a ruan lute as the other pauses playing a qin zither to listen; an attendant to the side with a fruit platter waits on them. Though the signature in the upper right indicates the artist is Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan, it is probably a spurious later addition. The theme of pausing the qin to listen to a ruan became popular in the Ming dynasty, with both blue-and-green and monochrome ink styles seen here. The arrangement of figures is also more or less similar, as if a Ming artist had composed it and added the name of a famous previous painter. Though ascribed to Zhao Mengfu, the style suggests this work was done around the 17th century.

“Fishermen Returning on a Frosty Bank” is by Tang Ti (ca. 1287-1355, a native of Zhejiang, initially studied the landscape style of Zhao Mengfu, but later also turned to the styles of Wei Yen, Li Cheng and Guo Xi. His greatest achievements, however, were as a follower of the Guo Xi tradition. In this painting three fishermen carry their gear as they converse while walking along a frosty bank. The crab-claw branches of the trees and cloud-head texturing of the slope in the foreground both derive from the style of Guo Xi. The flat distance composition, however, is from that of Li Cheng. The artist's inscription at the middle left dates the work to 1338, making it mature work. This is one of Tang Ti's masterpieces marked by a powerful brush and composition.

Yuan Portraits and Court Painting

Emaciated horse by Gong Kai

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “During the years of Mongol rule in the Yuan dynasty, court sponsorship of painting continued, but at nowhere near the levels of the previous dynasty. The Mongol rulers did continue the tradition of official imperial portraits, however. Except for their Mongolian clothing style, the portraits of Kublai Khan and his empress-consort Chabi follow the same conventions of pose and idealized likeness as their Han Chinese counterparts of the Song dynasty. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “As opposed to "leftover" painters and calligraphers who avoided or discriminated against the new "foreigners", some Chinese scholars chose to accept the Mongol Yuan court, in part as a way to perpetuate traditional Chinese culture. Chao Meng-fu (1254-1322), descendant of the Sung imperial clan, accepted the Yuan court's call to office, and he served in Confucian education and as a literary advisor to the emperor. Along with Hsien-yu Shu (1256-1302), who traveled from Hebei in the north to Hangchow to serve as an official, they dedicated themselves to revivalism in painting and calligraphy. They found new life in art through the practice and interpretation of ancient models. Their "Album of Calligraphy" reveals their enthusiastic discussion of painting and calligraphy by the ancients. Chao Meng-fu's painting of "Autumn Colors on the Ch'iao and Hua Mountains" for his friend Chou Mi uses a simple composition and calligraphic lines to portray a contemporary yet archaic landscape where reality and imagination fuse for a dream-like rendering of Chou's ancestral land. The painting, furthermore, serves as a vehicle for Chao's own desire to retreat to an idyllic life of reclusion. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei ]

“A Han Palace” is by Li Jung-chin (fl. ca. 14th century), who studied the ruled-line manner and landscape style of the Yuan artist Wang Chen-p'eng. “According to Miscellaneous Notes on the Western Capital, Councilor-in-Chief Hsiao had the Eternal Palace built in 200 B.C.. The buildings in this painting are grand and impressive, giving some idea of the form and structure of a Han palace. In addition to the fine and meticulous ruled-line manner for the architecture, the forms of the mountains and trees in the landscape setting as well as the moist brushwork all originated in the Li Cheng and Guo Xi tradition. Similar to that of Tang Ti, Li's contemporary in the Li-Kuo tradition, this work shows how popular and widespread the Li-Kuo style was in the Yuan dynasty. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Portraits of Emperors Taizu (Genghis Khan), Shizu (Kublai Khan) and Wenzong (Temur) were made by an anonymous artist. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The precious albums of Mongol Yuan imperial portraits in the collection of the National Palace Museum include eight leaves of emperors and fifteen leaves for consorts. Both albums were once in the former collection of the Nanxun Hall at the Qing court. The portraits in these album leaves were probably done on imperial order by Yuan court painters as small renderings of imperial visages. Painstaking brushwork was used to render facial hair with delicate washes of color for the eye sockets, highlighting the round full faces of these members of the Mongol aristocracy. The three Yuan emperors here have facial hair and wear monochrome robes, with Emperors Taizu (Genghis Khan) and Shizu (Kublai Khan) having a leather warming cap and Emperor Wenzong (Toq-Temur) a "seven-treasure layered hat." The thickness of the drapery lines varies slightly as well. These paintings of Mongol Yuan imperial visages might have been used as models for producing larger portraits or weaving tapestries, reflecting the tendency of Mongol rulers to adopt traditional Chinese culture at the time. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei ]

Dynastic rituals involving ancestral homage were major ceremonies in imperial China, and ruling clans often commissioned imperial portraits. Although the Mongols of the Yuan dynasty were not native Chinese, they also continued this practice. The imperial Yuan portraits are products of this functional need. In "Portrait of Emperor Shih-tsu (Kublai Khan)" and "Portrait of Kublai Khan's Consort (Chabi)", the eye sockets and cheeks were done using washes and rubbing, which differs from the traditional Chinese manner of single lines to delineate forms. Rather, it is closer to the artistic heritage of the Nepali and Tibetan region. Since the Mongols brought artists to court from different areas, the works that they had made at court therefore came to reflect a new style through the addition of non-native methods to traditional Chinese painting.

Paintings of Horses and Kublai Khan Hunting

Kublai on the Hunt

“Kublai Khan Hunting” by Liu Kuan-tao (fl. 13th century) is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 182.9 x 104.1 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Hunting was important in the lifestyle of steppe peoples, and the Great Khan in the Yuan dynasty held a large-scale fenced hunt every year. The grounds for the early spring hunt were set up in Liu-lin to the southeast of the capital Ta-tu (Peking). This work, done in 1280, is a representation of this important Mongol activity. Done by the court artist Liu Kuan-tao, he carefully described the clothes and accessories of Kublai Khan, his consort Chabi, and the figures attending them. This work thereby documents the high level refinement of objects used by the Mongols at court then. In addition to the meticulous and individual treatment of each figure, the features of hairstyle and skin color distinguish their ethnicity, providing a glimpse into the open multicultural atmosphere of the Yuan dynasty. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Liu Kuan-tao, a native of Hebei province, was a celebrated court painter of the early Yuan. His figure paintings were in the style of the early Chin and T'ang masters, while his landscapes followed the styles of Li Ch'eng and Kuo Hsi. His animal and bird-and-flower paintings combined the virtues of the old masters to become famous at the time. Appearing against a backdrop of northern steppes and desert is a scene of figures on horseback. The one sitting on a dark horse and wearing a white coat is most likely the famous Mongol emperor Kublai Khan with his empress next to him. They are accompanied by a host of servants and officials; the one to the left is about to shoot an arrow at one of the geese in the sky above. The figure wearing blue has a hawk famous for its hunting skills, and a trained wild-cat sits on the back of the horse in front. The dark-skinned figure is perhaps from somewhere in the Near East or Central Asia. In the background, a camel train proceeds slowly behind a sandy slope, adding a touch of life to the barren scenery. “Every aspect of this work has been rendered with exceptional detail. Appearing quite realistic, even the representation of Kublai Khan in this painting corresponds quite closely to his imperial portrait in the Museum collection. Though few of Liu Kuan-tao's paintings have survived, this work serves as testimony to his fame in Yuan court art. The artist's signature and the date (1280) appear in the lower left.” \=/

“Hunting on Horseback”, a attributed to an anonymous Yuan dynasty artist is an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 39.4 x 60.1 centimeters. Figures on horseback are shown entering autumn woods. The barren, sloping hills and the figures' clothing and equipage closely resemble those related to peoples north of China, a subject popular in painting since the Northern Song. Examples include "Lady Wen-chi's Return to China" attributed to the Song artist Ch'en Chu-chung and "Kublai Khan Hunting" by the Yuan artist Liu Kuan-tao. Though this work is attributed to an anonymous Yuan artist, details of the faces and style are quite close to "Portrait of Emperor Hsuan-tsung on Horseback" in the Museum collection. According to scholars, this is probably one of a number of works depicting the amusements of the Ming dynasty emperor Hsuan-tsung (1398-1435), here depicting him with his beloved Empress Sun and two female attendants on an autumn outing.

"“Six horses” is late 12th–early 13th century ink and color on paper handscroll, measuring 46.2 x 168.3 centimeters. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. "The disparities in paper, pigment, and style between the two halves of this painting make it clear that they are by different hands and from different periods. In the first half of the painting, the horses and figures are well drawn and there is a rough vigor in the depiction of the landscape and trees. The shading of the land forms and the bold modulated outlines defining the figures, who wear typical Khitan costumes, most closely resemble murals done in the eleventh and twelfth centuries in north China, then ruled by the Khitan Liao dynasty (907–1125). In the second half, the unmodulated, "iron-wire" lines used to describe the drapery folds of the rider, the heavy outline of the rock, and the dry calligraphic texture of the tree suggest a fourteenth-century date.

Yuan Buddhist and Taoist Art

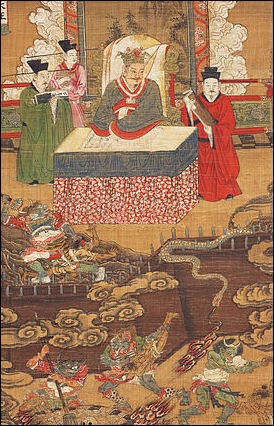

Ten Kings of Hell

Yuan period artists also produced their share of Buddhist and Tibetan Buddhist art. “The Buddha Preaching the Law”, according to the National Palace Museum, Taipei, is a woodblock print that reflects the new "Tibetan-Chinese" style of the Yuan dynasty. The main figures (the Buddha and bodhisattvas) are Tibetan in style, but the others (disciples, donors, etc.) are all Chinese in manner. Two major changes are also seen in terms of composition. First, the main Buddha is not placed in the center, but rather off to one side preaching the Buddhist law. Second, before the frontal Tibetan style pedestal is a diagonal donor table. It indicates that the Chinese printing of the south (which originally reflected Tibetan influences) is gradually returning to Southern Sung Chinese traditions. The sketchy manner of carving suggests that this print dates from the late Yuan.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

In "Reading Sanskrit in a Rain of Blossoms" a Buddhist monk from India is reading a scripture written in the Indian language of Sanskrit. He has dark skin as well as prominent facial features and body hair, indicating that he indeed is probably of Indian origin. Indian monks with exaggerated facial features were often seen in earlier paintings of lohans (arhats, disciples of the Buddha). However, in this work, the distinctive eyes and nose as well as the delicate portrayal of the hair seem to reflect an actual figure of the time, much like a portrait. In the Mongol empire, interaction between different ethnic groups increased rapidly and dramatically. Compared to previous periods, Yuan artists had a much greater opportunity of actually seeing monks and figures for other lands, such as India. Thus, this work may in fact be the product of cross-cultural experiences between ethnic groups in China at the time. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

On painting by Taoists and recluses, “Civil unrest erupted in the Kiangnan area of east-central China after the mid-1350s, and many scholars chose or were forced into reclusion or devoted themselves to Taoism. Of like mind, they formed close-knit circles in the Soochow, Hangchow, and Sungkiang areas. "Dwelling in the Fu-ch'un Mountains" by Huang Kung-wang (1269-1354) records the scenery in the artist's life of countryside reclusion. "Twin Pines (Junipers)" and "Bamboo and Rock" by Wu Chen (1280-1354) reflect the lofty and secluded nature of this scholar. Ni Tsan (1301-1374) used barren and lonely landscapes, such as in "Riverside Pavilion by Mountains", as a statement of psychological state at the time. "Spring Plowing at the Mouth of a Valley" and "Fishing in Reclusion at Cha-hsi" by Wang Meng (?-1385) both praise his friends' life of reclusion. Such Taoist painters and calligraphers as Fang Ts'ung-i (ca. 1302-1393) and Chang Yu (1283-1350) used either a simple and direct or a free and liberated approach, much in the Taoist philosophy of following nature. These artists did not seek to please others with their art, but instead focused on expressing their own emotions to create the definitive mode of literati painting and calligraphy. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated November 2021