EURASIAN ANIMALS WHEN THE FIRST HUMANS EMERGED

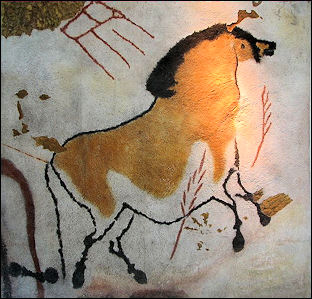

Lascaux horseAnimals that lived in Ice Age Europe around 40,000 years ago at same time modern humans and Neanderthal roamed the continent included wooly mammoths, cave bears, mastodons, saber tooth tigers, cave lions, wooly rhinoceros, steppe bison, giant elk, and the European wild ass.

In recent years major discoveries of mammoths, woolly rhinos, Ice Age foal, several puppies, cave bears and cave lion cubs as the permafrost melts across vast areas of Siberia due to climate change. [Source: Associated Press, September 15, 2020]

The largest primate ever was a Pleistocene ape that lived in southern China and Vietnam and had inch-wide teeth and is thought to have subsisted, like pandas, mainly on bamboo. A gigantic ape, standing over three meters (10 feet) tall and weighing up to 545 kilograms (1,200 pounds) lived roughly 2 million years ago to 300,000 years ago in Southeast Asia and China. This animal, Gigantopithecus blackii, was the largest primate ever. It may have co-existed with early homo species but unlikely lived at the same time modern men (homo sapiens). See Gigantopithecus Under PRIMATES — MONKEYS, MACAQUES, GIBBONS, AND LORISES—IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Gigantopitjecus may have lived as recently as 100,000 years ago, a time when humans were also thought to have inhabited the region. Jack Rink, a Canadian palaeontologist from McMaster University who is studying the creature, told the Times of London, “Probably the creature lived in the caves and fed in bamboo forests, while people were living lower in river valleys. It is quite likely that humans came face to face with the ape.”

See Separate Articles: ICE AGE ANIMALS IN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com ; WOOLLY MAMMOTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ; WOOLLY RHINOS europe.factsanddetails.com ; CAVE BEARS europe.factsanddetails.com AUROCHS europe.factsanddetails.com For Information on Gigantopithecus, the Largest Primate Ever SeeUnder PRIMATES — MONKEYS, MACAQUES, GIBBONS, AND LORISES—IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mammoths, Sabertooths, and Hominids: 65 Million Years of Mammalian Evolution in Europe” by Jordi Agustí and Mauricio Antón (2002) Amazon.com;

“Megafauna: First Victims of the Human-Caused Extinction by Baz Edmeades (2021) Amazon.com;

“Mega Meltdown: The Weird and Wonderful Animals of the Ice Age by Jack Tite Amazon.com;

“Animal World: Ice Age” by Camelot Editora, Francine Cervato, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Vanished Giants: The Lost World of the Ice Age” by Anthony J. Stuart (2024) Amazon.com;

“End of the Megafauna: The Fate of the World's Hugest, Fiercest, and Strangest Animals” by Ross D E MacPhee (Author), Peter Schouten (Illustrator) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History, from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us” by Steve Brusatte (2023) Amazon.com;

“Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age” by Adrian Lister and Paul G. Bahn (2015) Amazon.com;

“Smilodon: The Iconic Sabertooth” by Lars Werdelin, H. G. McDonald, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Giant Sloths and Sabertooth Cats: Extinct Mammals and the Archaeology of the Ice Age Great Basin by Donald Grayson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Clan of the Cave Bear: Earth's Children, Book One” by Jean M. Auel Amazon.com

Last Ice Age and Animals

Ice Age periods have occurred about 100,000 years or so for the last 2 million years. Around 125,000 years ago, in the middle of major warm, interglacial period, sea levels were 20 to 30 feet higher than they are today. Areas of Africa, the Middle East and West Asia that are desert today were covered by tropical deciduous forests and savanna dotted with numerous lakes.

After that the climate began getting colder. By around 100,000 years a new Ice Age had begun. About 65,000 years, in the middle of the ice age, glaciers covered nearly 17 million square miles, including much of northern Europe and Canada, and sea levels were more than 400 feet lower that they are today. Many islands and land masses that are now separated by ocean water were connected by land bridges. Among the land masses that were connected were Australia and Indonesia, and Alaska and Siberia. Around 40,000 years ago glaciers began to melt and sea levels rose again.

Northern Hemisphere Ice Age glaciation

Predation by early men and the shrinking of Ice Age grasslands are both believed to have led to the sudden extinction of wooly mammoths, cave bears, mastodons, saber tooth tigers, cave lions, wooly rhinoceros, steppe bison, giant elk, and the European wild ass. . Other species such as the musk ox and saiga antelope managed to survive in only small pockets. The mass extinctions are believed to have been partly the result of these animals having never been hunted by humans and having little fear of them.

Ice Age megafauna, including the woolly mammoth and the cave bear, became extinct around the same time around 10,000 years ago.. It is believed that these animals were driven to extinction by a mix of environmental factors, which may have also included competition for resources with modern humans, who were spreading throughout Europe and the Americas at this time.

The end of the large-game hunting cultures marked the end of the early stone age (Paleolithic period) and the beginning of the middle stone age (Mesolithic period) when early man derived his protein from fish, shellfish and deer instead of large animals like mammoth and buffalo.

See Separate Article ICE AGES AND ICE AGE GLACIERS factsanddetails.com

Was Tibet the Birthplace of Ice Age Animals?

Some scientists think Tibet is the source of Ice Age mammals. Fossil evidence indicates that woolly rhinos, may have evolved in the frigid highlands of the Tibetan Plateau 3.7 million years ago, more than 1 million years before global cooling allowed their descendants to spread throughout much of northern Eurasia. It had previously been that cold-adapted creatures such as mammoths and whooly rhinos evolved in the Arctic.

Stephanie Pappas wrote in LiveScience: “High on the Tibetan Plateau, paleontologists have uncovered the skull of a previously unknown species of ancient rhino, a woolly furred animal that came equipped with a built-in snow shovel on its face. This curiosity, a flat, paddle-like horn that would have allowed it to brush away snow and find vegetation beneath, suggests the woolly rhinoceros was well-adapted for a cold, icy life in the Himalayas about 1 million years before the Ice Age. Those adaptations may have left the rhino perfectly poised to spread across Asia when global temperatures plummeted, ushering in the Ice Age. "We think that the Tibetan Plateau may be a cradle for the origins of some of the Ice Age giants," said study author Xiaoming Wang, a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. Such large, furry mammals ruled the world during Earth's cold snap from 2.6 million to about 12,000 years ago. "It just happens to have the right environment to basically let animals acclimate themselves and be ready for the Ice Age cold." [Source: Stephanie Pappas, LiveScience, September 2, 2011]

Wang is researching where mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats and woolly rhinos originally evolved, which is still largely a mystery Sid Perkins wrote in Science: ““Previous studies suggested that 3.7 million years ago global average temperatures were as much as 3°C warmer than they are today. Also, Wang says, northern continents weren't covered with massive ice sheets that characterized the ice ages. Despite the warmth of the era, however, the Tibetan Plateau was about as cold and snowy as it is today, with an average temperature around 0°C and wintertime extremes sometimes dropping below -10°C. [Source: Sid Perkins, Science, September 1, 2011 ^|^]

“The researchers unearthed the fossils of more than two dozen species at the Tibetan field site, including extinct species such as three-toed horses and modern-day species such as the snow leopard and the chiru, also known as the Tibetan antelope. Because several of these creatures were known across a larger area during the recent ice ages, the researchers suggest that the Tibetan Plateau may have been their evolutionary cradle. Nevertheless, Wang notes, none of the fossils unearthed represent the woolly mammoths or mastodons so familiar to many, which suggests that those creatures may have evolved elsewhere. [Source: Sid Perkins, Science, September 1, 2011 ^|^]

“The new fossils "are quite fantastic," says Pierre-Olivier Antoine, a paleomammologist at the University of Montpellier 2 in France. A Tibetan origin of the woolly rhino "is quite surprising," he adds. Previously, scientists had suspected that the closest kin of woolly rhinos lived on the southern slopes of the Himalayas in Pakistan and India, but the newly described C. thibetana is obviously a much closer relative, he says. ^|^

“Scientists have previously suggested that many Ice Age-adapted mammals arose in the high Arctic, especially in the harsh conditions of a land bridge that joined northeastern Asia to what is now Alaska during ice ages, when sea levels were as much as 100 meters or so lower than they are today. However, "[a]n origin for the woolly rhino in Tibet, where high altitude imposed a regime of cold climate and open vegetation, makes perfect sense," says Adrian Lister, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London. "We know from today's species that they move up and down mountains in accordance with climate change and that many are now moving upwards to escape global warming," he notes. "It seems perfectly reasonable that a similar thing could have happened in reverse, over longer time scales, in the past."” ^|^

See Separate Article: WOOLLY RHINOS europe.factsanddetails.com

Oldest Big Cat Fossil Found in Tibet

Panthera blytheae

In November 2013, scientists announced they had discovered the oldest big cat fossils ever found — from a previously unknown species "similar to a snow leopard" — in the Himalayas in Tibet. The skull fragments of the newly-named Panthera blytheae have been dated between 4.1 and 5.95 million years old. The discovery, described by US and Chinese palaeontologists in an article published in the Royal Society journal Proceedings B supports the theory that big cats evolved in central Asia — not Africa — and spread outward. [Source: James Morgan, BBC, November 11, 2013]

The BBC reported: The scientists “used both anatomical and DNA data to determine that the skulls belonged to an extinct big cat, whose territory appears to overlap many of the species we know today. "This cat is a sister of living snow leopards — it has a broad forehead and a short face. But it's a little smaller — the size of clouded leopards," lead author Dr. Jack Tseng of the University of Southern California said. “This ties up a lot of questions we had on how big cats evolved and spread throughout the world>

“"Biologists had hypothesised that big cats originated in Asia. But there was a division between the DNA data and the fossil record." “The so-called "big cats" — the Pantherinae subfamily — includes lions, jaguars, tigers, leopards, snow leopards, and clouded leopards. DNA evidence suggests they diverged from their cousins the Felinae — which includes cougars, lynxes, and domestic cats — about 6.37 million years ago. But the earliest fossils previously found were just 3.6 million years old — tooth fragments uncovered at Laetoli in Tanzania, the famous hominin site excavated by Mary Leakey in the 1970s. Fossil skull of Panthera blytheae It is rare for such an ancient carnivore fossil to be so well preserved

Oldest Big Cat Fossil Found in Tibet See PREHISTORIC MAMMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Woolly Mammoths

Woolly mammoths lived from 400,000 to 3,900 years ago and for a while lived at the same time as American mastodons (who lived from 3.75 million to 11,500 years ago) and African elephants and Asian elephants (who first appeared about 4 million years ago). Woolly mammoths were like elephants adapted for cold weather. They had thick skin and a heavy Woolly coat. Reaching a height of 14 feet at the shoulder and possessing upward curving tusks, considerably larger than those of an elephant, they lived in North America and Eurasia.

Scientists have a good idea what woolly mammoths looked like based on the discovery of frozen woolly mammoth carcasses in Alaska and Siberia as well as bones and other remains found over a large area. In 2013, scientists found a baby woolly mammoth entombed in ice in Russia. Many woolly mammoth teeth and tusks have been discovered, some with human engravings on them. well. Early humans killed Woolly Mammoths for a number of reasons. They ate the meat, but they also made art, homes and tools out of the bones and tusks. [Source: extinct-animals-facts.com]

The ancestors of woolly mammoths and modern-day elephants originated in equatorial Africa. But between 1.2 and 2.0 million years ago, members of the mammoth lineage migrated to higher latitudes. Mammoths differ from elephants in a number of ways, such as having long and gracefully curved tusks instead of straight tusks and a domed skull instead of a flat head.

See Separate Article: WOOLLY MAMMOTHS europe.factsanddetails.com

Aurochs, A Favorite Stone Age Meat Source

Aurochs, wild Eurasian oxen with large curved horns, were larger than their descendants, modern domesticated cattle. They were a favored meat source. Some of the early people that ate its first consumed the bone marrow and then the ribs. Jennifer Viegas wrote in Discover News: ““Aurochs must have been good eats for Stone Age human meat lovers, since other prehistoric evidence also points to hunting, butchering and feasting on these animals. A few German sites have yielded aurochs bones next to flint tool artifacts. Aurochs bones have also been excavated at early dwellings throughout Europe. [Source: Jennifer Viegas, Discover News, June 27, 2011 ***]

.png)

auroch

“Bones for red deer, roe deer, wild boar and elk were even more common, perhaps because the aurochs was such a large, imposing animal and the hunters weren't always successful at killing it. At a Mesolithic site in Onnarp, Sweden, for example, scientists found the remains of aurochs that had been shot with arrows. The wounded animals escaped their pursuers before later dying in a swamp. ***

Today there are over 1.5 billion cows in the world and all — or at least nearly all — of them are believed to be descended from the aurochs. Members of the even-toed ungulate family and cousins of buffalo, musk oxen, wild oxen and yaks, aurochs were huge animals, standing two meters at the shoulder, with long horns. Bulls were black with a white stripe running down their back. Cows were slightly smaller and reddish brown in color. Domesticated cattle are much smaller than aurochs.

Reindeer and Caribou

Reindeer and caribou are the same animal ( Rangifer tarandus). The main difference is that reindeer are domesticated and found in Scandinavia and Siberia and caribou are wild and found in North America. There are two main kinds of caribou: woodland caribou and barren ground caribou (about a third smaller than woodlands caribou). Mountain reindeer are found in the ranges of Russia and northern Europe. [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perenial Library, Harper and Row, "Nomads" 99-108]

The reindeer that live today are pretty much the same as those that lived in Paleolithic times. Male reindeer and caribou are called bulls (or stags in some places). Females are called cows and youngsters, calves. Males often have whites clumps of hair that hang from their throats. Caribou and reindeer live primarily in the Arctic tundra, where the temperature average 23 degrees F throughout the year and can drop as low -76 degrees F. They are thought to have originated in North America. Up until 12,000 years ago they shared the Arctic tundra with wooly mammoths and mastodons.

Caribou and reindeer are the world's most widely distributed large land animals. As of the 1990s there were four million wild caribous in 200 herds: 102 in North America, 55 in Europe, 24 in Asia and 3 introduced herds on South Georgia Island in the southern Atlantic. Three fourths of these animals occur in just nine herds (eight in North America and one in Russia). In Alaska, there is a single herd with 600,000 caribou.

Woodlands caribou used to live as far south as Minnesota and Maine in the United States. Attempts to reintroduce them to these places have been thwarted in some places by a snail-bourne meningeal worm carried by white tail deer, who roam all over the United States. This parasite is relatively harmless to them but eats at the brain of caribou, moose, elk and other kinds of deer

Reindeer and Humans

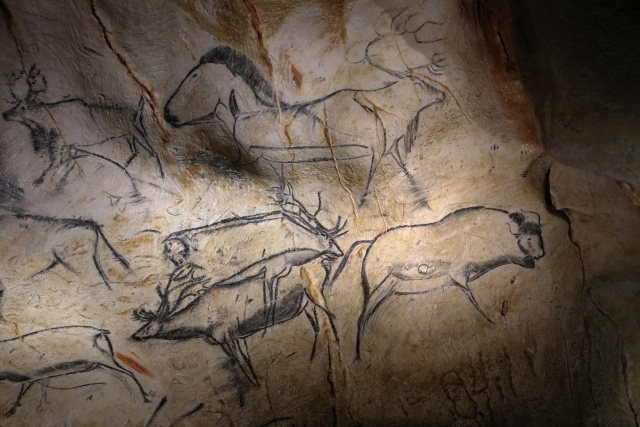

Mankind is believed to have stalked and hunted reindeer herds for at least 270,000 years. Archeological digs have revealed that Neanderthals ate reindeer for food 40,000 years. Images of reindeer have been found on 15,000-year-old cave paintings.

Reindeer were domesticated from wild reindeer (caribou) in northern Eurasia. When this took place is unknown. Reindeer are believed to have been domesticated between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago. Two forms of reindeer husbandry evolved. One on the open tundra where reindeer are gathered into large herds and moved between winter and summer pastures and other in the forest, where the animals are more difficult to supervise and herders manage smaller herds and supplements their diet with fish and other game.

Reindeer are difficult animals to ride but they can be harnessed and used to pull sleds or sledges. If you try to ride a reindeer, sit on the shoulders. If you sit on the back the animal will collapse under you. In Arctic regions and places with snow on the ground for long periods of time, reindeer are used to pull sleighs. They are strong enough to pulls sleighs with loads of 140 kilograms over frozen ground or snow for nine or ten miles an hour for several hours. Castrated reindeer are used as draft animals. Reindeer are often more efficient as transport animals in rugged country than horses.

Clothing, blanket, harnesses and other items are made from reindeer hide. Tight sinews are used for thread. Early autumn skins are prized for inter parkers consisting of an inner parka with the hair inside and an outer parka with the hair outside. Eskimos wore caribou-skin loincloths and caribou-skin socks with hair inside and caribou-skin boots with hair outside.

Reindeer are raised mainly for meat, hides, transportation and ability to pull loaded sleds. They are not good milk producers. While their milk is sweet ad creamy it is low in butterfat. Plus, a female reindeer produces only a pint of milk a day at most. White reindeer are greatly prized. They are regarded as a sign of wealth.

Ice Age Caribou Hunters

In the late 2000s, University of Michigan archaeologist John O’Shea read a book about modern-day reindeer herders living in the Subarctic and some of the elaborate stone structures they used to herd and manage their animals. He then wondered if Ice Age hunters in North America used similar devices 10,000 years ago around Lake Huron between Canada and the U.S. when the Alpena-Amberley land bridge existed and receding glacial ice sheets were just a few hundred kilometers to the north, making the area was ideal for caribou (reindeer). O’Shea then decided to survey areas underwater in Lake Huron that would have been above water 10,000 years, looking for caribou hunting structures. [Source: Jason Daley, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2018]

Jason Daley wrote in Archaeology magazine,: During one pass in the survey, a bright line of rocks stood out. The team sent an ROV down and found, to their surprise, that it was a man-made drive lane, a long stone alignment used to herd caribou into a corral, and a hunting blind where Paleoindians [Ice Age American Indians] would have waited to kill the animals. After that, over almost a decade of field seasons, O’Shea’s team identified more than 60 drive lanes and hunting blinds, as well as structures that were possibly caribou meat caches, all across the Alpena-Amberley Ridge.

O’Shea said. “There’s only a 2,000-year window where it was dry land. Then it was submerged and didn’t reemerge again.” Dating of the remains of ancient trees on the ridge based on wood samples and ancient pollen has shown that the land bridge would have indeed been a subarctic environment, said University of Texas at Arlington archaeologist Ashley Lemke, who has worked on the project for six seasons. She points out that while they moved across the ridge, Paleoindians would have encountered a rocky landscape with thin soils, covered in bogs and marshes. While the landscapes on the mainland were slowly developing into the grassland, savannah, and forest ecosystems that exist there today, the land bridge was covered in sparse clumps of trees such as spruce, tamarack, and aspen. “It was an Ice Age — like environment,” says Lemke. “That’s why caribou would be there. This is a place where the Ice Age lasted a little longer.”

“During the winter months, the ridge would have been brutally cold, leading O’Shea and his team to believe that the Paleoindians would not have lived there year-round. In the autumn, when caribou herds were healthiest, with the best meat and hides, O’Shea believes small family groups would camp on the land bridge as the animals migrated across it toward the southeast. The families would hunt in small groups, processing hides and drying and storing the meat in stone caches on the ridge for the winter. Because the cold winters froze the lake solid, O’Shea believes the caribou hunters would have been able to travel over the ice to the ridge in the winter and collect meat when they needed to.

“In the spring, as the herds of caribou headed up the ridge to the northwest, the hunters would have engaged in a different style of hunting, working in larger groups to herd the caribou down through stone drive lanes and processing large amounts of meat. “Spring is the direst time in northern climates,” says O’Shea, who notes that after enduring a harsh winter, the undernourished Paleoindians would have needed a way to get large amounts of meat quickly. “They used more complex hunting methods that took a lot of people to operate,” he says. “Then they would sit around for a couple of weeks eating caribou.”

Lemke, who is the primary ROV pilot for the team, explains that while the structures on the ridge were almost certainly built for hunting caribou, there is still scant evidence that the animals actually existed there — just one piece of burned caribou bone and a single tooth collected thus far. This can be explained by the fact that the hunting structures they’ve been able to study, she says, would have been kept meticulously clean of bone and animal debris, since the scent of blood would scare off other caribou. Butchering and processing the animals would have taken place at other sites or at the camps where the hunters lived. These should be full of bones and evidence of the presence of caribou. “We’ve gotten good at finding out where they were hunting,” says Lemke. “Now we’re curious where they were living.”While watching video collected from an ROV exploring a drive-lane site called Drop 45, O’Shea noticed two stone circles, similar to tepee rings found in the western United States. A preliminary excavation found remnants of a fire hearth in the middle of the ring, a good indication that this was one of the long-sought habitation sites. The stone circles will be a major focus next season.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Where the Ice Age Caribou Ranged”, Archaeology magazine archaeology.org

Did Prehistoric Worms Frozen in Siberian Permafrost Come Back to Life After 40,000 Years

A widely-shared November 2, 2021 Facebook post read: “"Russian scientists defrosted several prehistoric worms, which were frozen in Arctic permafrost for around 40,000 years," A graphic of an animal that looks like a worm but with a monstrous gaping mouth and many sharp teeth claimed two of the worms collected "began moving and eating" after being left out to thaw.

According to USA TODAY: In 2015, Russian scientists did uncover two worms that were estimated to be around 32,000 years old and 41,700 years old based on dating of the soil samples they were found in. Both worms were revived after being thawed at warm temperatures for several weeks. The image accompanying the post predates the finding and is a 3D sculpture created by a Poland-based illustrator. [Source: Miriam Fauzia, USA TODAY, November 16, 2021]

“The worms mentioned in the Facebook post were discovered in a region of northeastern Siberia called Yakutia. Other ancient, preserved animals have been found in the area, including the frozen remains of a 50,000-year-old, extinct cave lion cub.“In collaboration with Princeton University, Russian scientists isolated the worms after analyzing over 300 soil samples collected from the Arctic permafrost, Live Science reported in 2018. “The two worms — both female — came from two known species called Panagrolaimus detritophagus and Plectus parvus.

“Scientists estimated one specimen was around 32,000 years old and the other was around 41,700 years old. These estimates were based on radiocarbon dating of the sites where the worms were recovered, according to a 2017 paper by the Russian research group. After spending several weeks thawing in a petri dish at 68 degrees, the resurrected worms reportedly moved around, ate food and even cloned new family members, Gizmodo reported.

“Worms, known scientifically as nematodes, and their close relative the tardigrade have been known to weather severe environmental conditions. Some have previously been revived after being dormant for 30 to 39 years, Science Alert reported. But there have been no records of these worms surviving over several millennia. This has had some scientists concerned over whether the creatures are actually tens of thousands of years old, or if there had been potential contamination with contemporary samples. “"Okay so: I was understandably incredulous to read this; 41,000 years is unheard of in terms of organisms surviving deep freeze, by orders of magnitude," tweeted Jacquelyn Gill, a paleoecologist at the University of Maine, in 2019.

“Gill noted that while 32,000-year-old plant seeds have successfully bloomed into flowers, it was trickier to confirm the nematodes originated that long ago. She pointed out that the Russian scientists had dated the permafrost samples — not the nematodes themselves — and that the samples weren't sieved for eggs or adult worms. "They took 1-2 grams of frozen soil, added liquid nematode food, and heated (it) to room temperature for several weeks," Gill said. "This is crucial, because from what I can tell reading this paper, we have no supporting evidence that the nematodes originated in the sediment and aren't modern contamination."

“Tatiana Vishnivetskaya, a microbiologist at the University of Tennessee who co-authored the 2018 study, said contamination was unlikely because the samples came from a type of permafrost that is syncryogenic — when freezing and sediment accumulation happen at the same time. "By definition, it was assumed that nematodes were frozen along with sediment deposition, so we used the sediments to obtain radiocarbon age," Vishnivetskaya said in an email to VICE in 2019. "Our team is very cautious about sterility and aseptic techniques especially when we collect samples for microbiology and molecular biology studies," she added. "We are pretty sure no contamination with upper soil happens during sampling."

Plants Grown from Fruit Stashed Away 30,000 Years Ago by Squirrels

Scientists in Russia have grown plants from fruit — found in the banks of the Kolyma River in Siberia, a top site for people looking for mammoth bones — stored away in permafrost by squirrels over 30,000 years ago. Richard Black of the BBC reported: “The Institute of Cell Biophysics team raised plants of Silene stenophylla – of the campion family – from the fruit. Writing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), they note this is the oldest plant material by far to have been brought to life. Prior to this, the record lay with date palm seeds stored for 2,000 years at Masada in Israel. [Source: Richard Black, BBC News, February 20, 2012 |::|]

“The leader of the research team, Professor David Gilichinsky, died a few days before his paper was published. In it, he and his colleagues describe finding about 70 squirrel hibernation burrows in the river bank. “All burrows were found at depths of 20-40 million from the present day surface and located in layers containing bones of large mammals such as mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, bison, horse, deer, and other representatives of fauna from the age of mammoths, as well as plant remains,” they write. “The presence of vertical ice wedges demonstrates that it has been continuously frozen and never thawed. Accordingly, the fossil burrows and their content have never been defrosted since burial and simultaneous freezing.” |::|

“The squirrels appear to have stashed their store in the coldest part of their burrow, which subsequently froze permanently, presumably due to a cooling of the local climate. The fruits grew into healthy plants, though subtly different from modern examples of the species Back in the lab, near Moscow, the team’s attempts to germinate mature seeds failed. Eventually they found success using elements of the fruit itself, which they refer to as “placental tissue” and propagated in laboratory dishes. “This is by far the most extraordinary example of extreme longevity for material from higher plants,” commented Robin Probert, head of conservation and technology at the UK’s Millennium Seed Bank. “I’m not surprised that it’s been possible to find living material as old as this, and this is exactly where we would go looking, in permafrost and these fossilised rodent burrows with their caches of seeds. “But it is a surprise to me that they’re finding viable material from this placental tissue rather than mature seeds. |::|

“The Russian team’s theory is that the tissue cells are full of sucrose that would have formed food for the growing plants. Sugars are preservatives; they are even being researched as a way of keeping vaccines fresh in the hot climates of Africa without the need for refrigeration. So it may be that the sugar-rich cells were able to survive in a potentially viable state for so long. |::|

“Silene stenophylla still grows on the Siberian tundra; and when the researchers compared modern-day plants against their resurrected cousins, they found subtle differences in the shape of petals and the sex of flowers, for reasons that are not evident. The scientists suggest in their PNAS paper that research of this kind can help in studies of evolution, and shed light on environmental conditions in past millennia. But perhaps the most enticing suggestion is that it might be possible, using the same techniques, to raise plants that are now extinct – provided that Arctic ground squirrels or some other creatures secreted away the fruit and seeds. “We’d predict that seeds would stay viable for thousands, possibly tens of thousands of years – I don’t think anyone would expect hundreds of thousands of years,” said Dr Probert. “[So] there is an opportunity to resurrect flowering plants that have gone extinct in the same way that we talk about bringing mammoths back to life, the Jurassic Park kind of idea.”“ |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024