MONKEYS AND PRIMATES IN CHINA

Yunnan snub-nosed monkey China is home to 21 primate species including snub-nosed monkeys, gibbons, macaques, leaf monkeys, langurs and lorises. The monkey is one of the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac. Apes and monkeys, particularly gibbons and macaques, are fixtures of traditional Chinese folk religion, culture art and literature. Wukong — the Monkey King, from “Journey to the West” — is one China’s most beloved literary and folklore characters. Most of China's primate species are endangered. Despite they are sometimes hunted for food and monkey brain is eaten as a delicacy some places in Guangxi and Guangdong as well as Taiwan. Many monkeys used in laboratory work originate in China. [Source: Wikipedia]

Monkeys found in China include the François' langur, white-headed langur, Phayre's leaf monkey, capped langur and Shortridge's langur, which are collectively categorized as lutungs and the Nepal gray langur, which is considered a true langur. Lutungs, also called leaf monkeys, have relatively short arms, longer legs and long tails along with a hood of hair above their eyes. François' langur is found only in southwest China and northern Vietnam. Phayre's leaf monkey is native to Yunnan and a large area of Indochina. The capped and Shortridge's langurs live along the Yunnan-Myanmar border. The Nepal gray langur is found in southern Tibet. All of these species are endangered.

The most commonly found primates in China are macaques. The only apes native to China are the gibbons. Some lorises are found in China. The pygmy slow loris and Bengal slow loris are both found in southern Yunnan and Guangxi and are Class I protected species. (See Below).

In June 2003, AP reported: “Four monkeys escaped from a zoo in northeastern China and attacked a woman and her baby before three of the animals were shot to death by police, the official Xinhua News Agency said Wednesday. The three adult monkeys and one baby escaped Monday from a zoo in Changtu county in Liaoning province, Xinhua said. It did not say what species they were. The monkeys took refuge in a grove of trees and resisted attempts to recapture them, the report said. "One of the monkeys pounced on a woman holding a child, biting her arm before leaping back into the tree," Xinhua said. It said police shot the adult monkeys "to prevent further attacks." The baby monkey escaped and is still at large, Xinhua said.- Monkeys from Chinese zoo attack woman and baby, are killed by police. [Source: AP, June 25, 2003]

ANIMALS AND PLANTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com Golden Monkey Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Primate Info. Net pin.primate.wisc.edu; On Wild Animals in China: Living National Treasures: China lntreasures.com/china ; Animal Info animalinfo.org Animal Picture Archives (do a Search for the Animal Species You Want) animalpicturesarchive Animals Asia Campaign to Help Animals animalsasia.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Biology of Snub-Nosed Monleys, Douc Langurs, Proboscis Monkeys, and Simakobus by Cyril C. Grueter Amazon.com; “Tales of the Golden Monkeys” by Yong Yange Amazon.com; “Chinese Wildlife” ( Bradt Travel Wildlife Guides) by Martin Walters Amazon.com; “Guide to the Wildlife of Southwest China” by William McShea, Sheng Li, et al. Amazon.com; “Wild China: Natural Wonders of the World's Most Enigmatic Land by Phil Chapman, George Chan, et al. Amazon.com; “Wildlife of China” by China Wildlife Conservation Association Amazon.com; “Wildlife Wonders of China: A Pictorial Journey through the Lens of Conservationist Xi Zhinong” by Zhinong Xi, Rosamund Kidman Cox, et al. Amazon.com; “Mammals of China (Princeton Pocket Guides” by Andrew T. Smith and Yan Xie Amazon.com; “China Red Data Book of Endangered Animals: Mammalia” by Wang Song Amazon.com; “Rare Wild Animals” (Culture of China) by Yang Chunyan, Zhang Cizu, et al. Amazon.com

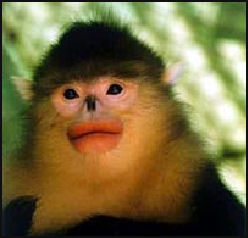

Snub-Nosed Monkeys

Yunnan snub-nosed monkey Snub-nosed monkeys (also known as snub-nosed langurs) are able to survive in cold temperatures better than any other primate. They live in areas that are covered in snow as much as half of the year; endure winters with sub zero temperatures; and live at elevations up to 4,500 meters, although during the winter they usually descend to lower elevations.

have a head and body length between 51 and 67 centimeters and a tail length of 51 to 97 centimeters. They spend most of their time in trees but come to ground for some feeding and social activities. If threatened they can race through the upper levels of the canopy at great speeds.

Snub-nosed monkeys are among the most endangered primate species in Asia. They have been hunted for centuries for their pelts and body parts, for Chinese medicine. The Manchu valued their pelage which was believed to ward off rheumatism. There are only a few hundred or a few thousand left of each species.

See Separate Article SNUB-NOSED MONKEYS AND GOLDEN MONKEYS factsanddetails.com ;

Macaques in China

The most commonly found primates in China are macaques. They sometimes live in large troops and include the rhesus or common macaque, who range extends from as far north as the Taihang Mountains of Shanxi to Hainan Islands. Stump-tailed macaques have distinctive red faces and are found in southern China. Tibetan macaques can be seen at tourist sites such as Mount Emei and Huangshan. The Formosan rock macaque lives in Taiwan. The northern pig-tailed macaque is endemic to Yunnan. Assam macaques are found in higher elevation areas of southern Tibet and the Southwest. The Monpa and Lhoba people of southern Tibet eat Assam macaques [Source: Wikipedia]

The rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatto) is mainly distributed in the broadleaved forest, the theropencedrymion, the bamboo forest and bare rocks with sparse trees in the Wolong Natural Reserve. Making its home in caves or cliffs, they may also sleep in the tree at night. A group of rhesus macaques has no certain number, but often 40 to 50 members. With acute hearing and vision, it is also good climber and agile jumper among the trees. It can swim through rivers. At daytime, rhesus macaques often search for food among the trees or frolicking on the ground. Its sundry diet consists of wild fruits, wild vegetables, tender shoots and leaves, blossoms, and bamboo shoots, sometimes even small birds, bird eggs, and insects. At harvest time, they may also take crops for food. The mating season of the macaque is uncertain. After about 150 to 165 days' pregnancy, a pregnant female macaque often gives birth to one cub or two cubs occasionally, mostly in summer. On China’s National List for Specially Protected Wild Animals, the rhesus macaque is listed as a threatened species. [Source: Science Museum of China kepu.net.cn]

Assamese macaques (Macaca assamensis) have a body length of 50-66 centimeters and a tail length of 17-23 centimeters. Their preferred habitats are tropical and sub-tropical forests. They catch prey or pick fruit with their hands in treea and eat wild fruits, young leaves of trees and bushes and insects. They live in groups and mostly spend their time in trees. Compared with other types of macaques, their faces are longer and their anused are more protruding. They can be found in Southern Yunnan and Southern Southwest China. They are regarded as an endangered species.

Pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) have a body length of 50-66 centimeters and a tail length of 17-3 two centimeters. They live in tropical and sub-tropical forests and pick fruit and leaves in trees or catch small living creatures on the ground and eat leaves of trees and bushes, insects and small birds. They live in groups and often spend their time on the ground. The top of their head is flat with some whorls of hair. The tail is like that of a pig; hence their names "flat-headed macaque" or "pig-tailed macaque".

(Presbytis phayrei) have a body length of 55-71 centimeters and a tail length of 60-80 centimeters. Their preferred habitats are tropical or sub-tropical forests. They pick flowers, fruit and young leaves on trees with their hands and catch small birds and eat various kinds of vegetation of various kinds and small birds. They seldom come down to the ground. Group consists 10 to 60 macaques. Phayre's Leaf Macaques can be found only in scattered groups in southwest Yunnan. They are regarded as an endangered species.

See MACAQUES AND RHESUS MONKEYS factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Macaque

Tibetan Macaques (Macaca thibetana) have a body length of 55-67 centimeters and a tail length of 6-10 centimeters and weigh 10-25 kilograms. They live in tropical and sub-tropical forests and pick foods on the ground or pick fruit and young leaves with their hands and eat fruits, young leaves of trees and bushes, insects and small birds. They can be found in Northeast of Yunnan. Central China, Eastern China and Southern China. They are regarded as threatened not endangered species. [Source: Science Museum of China kepu.net.cn]

Tibetan Macaques are an endemic species of China. They live in groups in high mountains or forests and tend to spend their time on the ground rather in trees. In Sichuan they are mainly found in evergreen broad-leavedforest or the mixed deciduous forest, as well as shrub forest along river valleys. Diurnal in its habits, Tibetan macaque have has no fixed territory. Divided into several groups, a big family of Tibetan macaques often sleep in a circle — with the young macaques in the center — when they are next a rock wall. A small family of Tibetan macques may consists of 20 to 40 members while a big one may have 50 to 70 or even more. The strong male macaques lead the whole family; but when those "monkey kings" become old, they live in solitude away from the family.

Vertical migration is a common trait of the Tibetan macaque. The diet of the Tibetan macaque mainly consists of vegetarian foods: tree leaves, seeds and fruits, bamboo shoots; but sometimes it may also eat some lizards and small birds. In autumn, the macaques may take corn and other crops for food. The mating season of the Tibetan macaque can be all through the year. After about six months' pregnancy, a female macaque gives birth to one cub or two cubs mostly in April or May.

There are large groups of Tibetan macaques on Emei Mountain in Sichuan and Huangshan Mountain in Anhui. They are familiar with tourists and don't fear people at all. The Tibetan macaques of Emei Mountain can be particularly naughty. Because so many tourists have given them food, they have cultivated many bad habits. The macaques often hang around on the mountain paths to force tourists to give them food. If the tourists refuse to give them food, they can bite or scratch them. Sometimes they steal tourists' bags and rummage through the bags in trees and tourists' cameras, wallets or glasses into deep valleys. Some tourists, scared by the macaques, have fallen down from the mountain or were even pushed down to deep valleys by the them. Some articles have suggested tourists should give more food to the macaques to prevent them from being aggressive. But actually the opposite is true. Giving them food just encourages them. It is best not to feed them to encourage them restore their normal behavior.

See SOUTH OF CHENGDU: MT. EMEI, DINOSAURS, THE GIANT BUDDHA AND THE ROCKET-LAUNCHING ANCIENT TOWN factsanddetails.com

Gibbons in China

Gibbon

Gibbons are tree-dweller apes that use their long arms to swing from tree branch to tree branch. Gibbons are known for their loud calls and mating pairs who often sing together in duet. Two species of gibbon have disappeared in China and all surviving Chinese specie are classified as Critically Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Hoolock gibbons (Hylobates hoolock) have a body length of 45-58 centimeters. Similar to black gibbons, they live in old growth tropical forests or secondary tropical forests and pick young leaves, fruit or catch small animals with hands and eat young leaves of trees and bushes, fruits, insects and small birds. They can be found in southwest Yunnan. They are regarded as an endangered species. [Source: Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net]

White-cheeked gibbons (Hylobates leucogenys) have a body length of 42-52 centimeters. Their preferred habitats are low-elevation tropical forests. They pick young leaves and fruit and catch small animals with hands. They eat young leaves of trees and bushes, fruits, insects and small birds. They can be found in Xishuangbanna of Yunnan. They are regarded as an endangered species.

About 100 cao vit gibbons still live along the Vietnam-China border. It was once thought to have been hunted to extinction. Concolor gibbons have had their numbers reduced by poaching and loss of habitat resulting from farming. Males are black and females are golden or tawny brown. They survive in isolated areas of Laos, Vietnam and China. There could be as few as 10,000 left. Animal behaviorist Janine Benyus wrote: "Females can be picky and, because the world's captive community is so limited, finding a compatible mate can be like dating in a very small town."

GIBBONS: TREES, SONGS, MOTHERS AND DIFFERENT SPECIES factsanddetails.com

White Headed Langur

White-headed langurs (Trachypithecus leucocephalus, Tan, 1957) are gray in color. They live in Southern China. They are 40–76 centimeters (16–30 inches) long, with a 57–110 centimeter (22–43 inch) tail. They live in and eat leaves, flowers, and fruit. They are critically endangered. There are only 230–250 of them. Their population is declining.

The white-headed langur lives main in an area of karst mountains in Guanxi Province. Adults are black with white heads and black faces. Infants are yellow. Infanticide — in which a male takes over a group and kills all the newborns presumably so females can start ovulating and bear the male’s offspring — is practiced.

Adult white-headed langur are black with white heads and black faces. Infants are yellow. Their head and body length of the is 47 to 62 centimeters; Their weight is 6.7 to 9.5 kilograms. White-headed langur spend a majority of their time on rocky surfaces, sleeping in caves and crevices in limestone cliffs. In the winter they like to sunbathe on the rocks. In the summer they seek shade under the rocks. They mostly forage on leaves, with leaves constituting 92 percent of their diet in some months. They are victims of poaching and survive in 16 isolated habitat fragments. .[Source: Canon advertisement]

The white-headed langur is a critically endangered langur. The golden-headed or Cat Ba langur — regarded as a subspecies — lives on Cat Ba Island, Vietnam (T. p. poliocephalus). Both are blackish, except for their crown, cheeks and neck which are yellowish in the golden-headed variety but are white in the golden-headed langur. As is the case with all members of the Trachypithecus francoisi species group, these primates are social and diurnal and found in limestone forests. The golden-headed Ba langur is among the rarest primates in the world, and possibly the rarest primate in Asia. [Source: Wikipedia]

The surviving number of white-headed langur in 2002 was 580-620 The population of white-headed langur dropped from around 2,000 individuals in the late 1980s to fewer than 500 in the mid 1990s to due mainly to poaching by non-locals to supply wildlife food market. Since then their numbers have increased mainly by encouraging local villagers to help the monkeys by preserving the forest where they live and driving away poachers. Conservationists achieved these gains by providing clean water to the villagers to earn their trust and cooperation and building biogas convertors to keep them from cutting down trees. The programs has been so successful it has been held up as a model for saving endangered animals in other localities. Pan Wenshi, a conservationist known for his work with pandas, has been the leader in the drive to save the langurs. He helped set up a 24-square-kilometer nature reserve where most the langurs live and initiated the programs to get villager involved in saving them.

LANGURS factsanddetails.com; LANGURS OF SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

Gigantopithecus

Gigantopithecus

Gigantopithecus blacki was the largest primate ever. It stood three meters tall (10 feet) and weighed up to 300 kilogrammes (660 pounds). It ate fruit, bamboo, bark and other vegetation and lived roughly from 2 million years ago to 200,000 years ago in the forests of Southeast Asia and China. Gigantopithecus may have co-existed with early homo species but unlikely lived at the same time modern men (homo sapiens).

Gigantopithecus blacki was discovered in the 1930s by German scientist who stumbled on one of its teeth at a Hong Kong apothecary. The molar was so massive it was being sold as a "dragon's tooth". "It was three to four times bigger than the teeth from any great ape," Renaud Joannes-Boyau,a researcher at Australia's Southern Cross University, told AFP. All that has been found of the Gigantopithecus since are four partial jawbones and around 2,000 teeth, hundreds of which were discovered inside caves in southern China's Guangxi province. [Source: Juliette Collen with Peter Catterall in Beijing, AFP, January 11, 2024]

Bjorn Carey wrote in in Live Science: “Since the original discovery, scientists have been able to piece together a description of Gigantopithecus using just a handful of teeth and a set of jawbones. It may not be much, but the unusually large size of these teeth indicates they belonged to one big ape. Jack Rink, a geochronologist at McMaster University in Ontario, said: "The size of these specimens – the crown of the molar, for instance, measures about an inch across – helped us understand the extraordinary size of the primate." [Source: Bjorn Carey, Live Science, November 7, 2005 ^]

“Further studies of the teeth revealed that the ape was an herbivore, and bamboo was probably its favorite meal. Researchers do not have a full skeleton for Gigantopithecus. But they can fill in the gaps and estimate its size and shape by comparing it to other primates – those that came before it, coexisted with it, and also modern apes. Currently, scientists are debating over how Gigantopithecus got around – was it bipedal or did it use its arms to help it walk, like modern chimpanzees and orangutans? The only way to answer this is to collect more bones.” ^

Gigantopithecus and Orangutans

Genetic material extracted from a 1.9 million-year-old "Giganto" fossil tooth from southern China shows was a cousin of today's orangutans. Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: “Scientists were able to obtain genetic material — dental enamel proteins — from a broken molar with thick enamel discovered in Chuifeng Cave in China's Guangxi region. The researchers concluded the tooth may have belonged to an adult female. "Our data, for the first time, provides independent molecular evidence that the closest living relative of Gigantopithecus is the modern orangutan," said University of Copenhagen molecular anthropologist Frido Welker, lead author of the study published in the journal Nature. "Not only do proteins survive, but they survive in sufficient quantities to enable resolving the evolutionary relationships between Giganto and extant great apes," Welker added, referring to the group that includes orangutans, gorillas, bonobos and chimpanzees. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, November 13, 2019]

“The orangutan and Gigantopithecus evolutionary lineages split about 12 million years ago, the researchers said. "A long-unresolved issue comes to a solution," said paleoanthropologist and study co-author Wei Wang of Shandong University in China. "Its origin and evolution have puzzled paleoanthropologists for more than half a century." It marked the first time that genetic material this old has been recovered from a fossil found in a warm, humid environment — conditions usually inhospitable to such preservation. The researchers expressed hope the same technique can be used on other fossils, perhaps including species in the human evolutionary lineage.

Wang said Gigantopithecus may have had an orangutan-like appearance and most likely was a ground-dweller, unlike orangutans, which spend most of their time in trees. It likely had a plant-based diet, perhaps eating sweet foods like fruit in forested environments, judging from the cavities seen in its teeth, Wang said. The reasons for its extinction are not fully understood. Wang said environmental and climate changes may be to blame Our species, Homo sapiens, first appeared about 300,000 years ago in Africa, only later reaching Southeast Asia, meaning it is unlikely the two species met. Wang saw no evidence of other now-extinct human species playing a role in the Gigantopithecus demise.

Gigantopithecus’s Huge Size Eventually Sealed Its Doom

Exactly why Gigantopithecus died off has perplexed palaeontologist since the great ape was discovered. In a study published in the journal Nature in January 2024 by Joannes-Boyau, a researcher at Australia's Southern Cross University, and Yingqi Zhang of China's Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Gigantopithecus went extinct because it could not adapt to its changing environment and was reduced to living off bark and twigs before dying out. [Source: Juliette Collen with Peter Catterall in Beijing, AFP, January 11, 2024]

AFP reported: Seeking to establish a timeline of the animal's existence, the team of Chinese, Australian and US scientists collected fossilised teeth from 22 caves. The team used six different techniques to determine the age of the fossils, including a relatively new method called luminescence dating which measures the last time minerals were exposed to sunlight. The oldest teeth dated back more than two million years, while the most recent were from around 250,000 ago. Now the researchers can tell "the complete story about Gigantopithecus's extinction" for the first time, Zhang told AFP in his office in Beijing.

They established that the animal's "extinction window" was between 215,000 and 295,000 years ago, significantly earlier than previously thought. During this time, the seasons were becoming more pronounced, which was changing the local environment. The thick, lush forest that Gigantopithecus had thrived in was starting to give way to more open forests and grassland.

This increasingly deprived the ape of its favourite food: fruit. The huge animal was bound to the ground, unable swing into the trees for higher food. Instead, it "relied on less nutritious fall-back food such as bark and twigs," said Kira Westaway, a geochronologist at Australia's Macquarie University and co-lead author.

Zhang said this was a "huge mistake" which ultimately led to the animal's extinction. The primate's size made it difficult to go very far to search for food — and its massive bulk meant that it needed plenty to eat. Despite these challenges, "surprisingly G. blacki even increased in size during this time," Westaway said. By analysing its teeth, the researchers were able to measure the increasing stress the ape was under as its numbers shrunk.

They also compared Gigantopithecus' fate to its orangutan relative, Pongo weidenreichi, which handled the changing environment far better. The orangutan was smaller and more agile, able to move swiftly through the forest canopy to gather a variety of food such as leaves, flowers, nuts, seeds, and even insects and small mammals. It became even smaller over time, thriving as its massive cousin Gigantopithecus starved.

Lorises in China

slow loris

Slow Lorises (Nycticebus coucang) have a body length of 32-35 centimeters and weigh about 1000 grams. Their preferred habitats are tropical and sub-tropical forests and catch their prey or pick fruit with their hands and mouth in tree trunks or in branches and eat wild fruits, insects, small birds or eggs of birds. They can be found in southern Yunnan and southern Guangxi. They are regarded as endangered species.

Slow lorises are primates who live in trees and are generally solitary . They curls up like a ball in the holes of trees or in-between dense branches and twigs during the daytime and go out to seek food in the night and usually move around slowly. In China they are sometimes called he "lazy macaque". Their movements are quick and accurate when they catch insects, which are quite different from their usual behaviors. Their gestation period is 5 to 6 months. Females give birth to one young at a time. Young slow lorises climb on the back of their mothers to seek food.

Intermediate Slow Lorises (Nycticebus intermedous) have a body length of 20-25 centimeters and weigh about 250 -300 grams. They live in tropical and sub-tropical forests. They catch their prey or pick fruit with their hands in tree trunks or in branches and eat leaves of trees and bushes, insects and small birds. Their habits are similar to those of the slow loris. Since they are smaller in size, they are commonly called "small lazy macaque" in China. They were not found in China until 1978. They can be found in only in Southern Yunnan. They are regarded as an endangered species.

See Separate Article LORISES factsanddetails.com

Old Fool: Elegy for a Monkey (Loris)

Hu Fayun wrote: Old Fool is a tiny monkey. He’s not a kind of monkey we commonly see, but one that’s on the verge of extinction....Early last winter, my wife returned from the wet market and reported seeing a peddler selling two tiny monkeys; they were caged in a wire rattrap, curled up pitifully into little balls and huddled together to escape the cold. Each time my wife returned from the wet market she brought back a few of these heartrending stories: about a wounded muntjac deer with melancholy eyes; about a few small hedgehogs fighting fruitlessly to break free from a nylon net bag; about a row of brilliantly plumaged golden pheasant corpses; about a small squirrel struggling in the scorching sun for its final dying breath; about a clowder of cats crushed together and yowling piteously in chorus. There were also small squawking quail bouncing frenziedly in a basket, bare and bloody from being plucked featherless while alive. There were frogs, tortoises, soft-shelled turtles, and snakes—all of which, as recipes prescribe, had been skinned alive. There were also those docile and adorable pigeons, rabbits, and lambs. For these small creatures, every wet market is their Auschwitz concentration camp.[Source: "Old Fool: Elegy for a Monkey" by Hu Fayun, MCLC Resource Center, translated by Paul E. Festa, August 2017

“But this time it was the two monkeys. Monkeys have much in common with humans; it’s said we share a common ancestry. The monkeys merely live according to their instincts and stay up in the trees. Humans, by contrast, climbed down from the trees and became bipedal plains inhabitants; we learned how to make the javelin and stone axe, the broadsword and long spear, and eventually guns and rockets capable of slaughtering all life on the planet, including ourselves.

“My wife said she wanted to buy those two monkeys right then and there. Even if she bought them, what would be accomplished? The next day there’d be four more monkeys for sale. What’s more, could we offer them happiness and wellbeing? Could we give to them the life they require? Our home already had a half-dozen cats and dogs; would they get along with the monkeys? Over the last few years, we’ve raised a Noah’s ark of animals: cats, dogs, tortoises, frogs, hedgehogs, pigeons, parrots, grasshoppers, goldfish, tadpoles, loaches . . . not a one didn’t reach a tragic end, or won’t reach a tragic end. The longer they remain alive, the deeper grows our attachment to them, and so the more tragic is their ending. We’ve already buried a bunch of our animals in our downstairs flowerbed, a patch of which is a cemetery with no gravestones. It’s as if we’re atoning for humanity’s crimes against animals. My wife often remarks that people are the most evil creatures on the planet.

“The next day, my wife went back to the wet market. She found remaining only one monkey, which she said looked even more miserable (we don’t know if the other monkey was sold or if it died). She was bent on buying that monkey, so I told her to go ahead with it. She thereupon went and invited the monkey peddler back to our house. The peddler held in his hand a small wire cage with the monkey inside. The monkey was motionless and curled up tightly into a ball, with its head buried deep in its bosom. The peddler reached into the cage and grabbed the monkey; its head was still down and buried, while its hands and feet clung tightly to the cage’s iron mesh. By the time the peddler finally yanked the monkey free from the cage, the monkey’s fingers and toes were bloody where the iron wire sliced into them. The monkey was truly Lilliputian, only five or six inches tall; including its long and slender arms and legs, it was still under a foot. It was also exceedingly slight, couldn’t weigh more than a jin; holding it in your palm you could feel discretely on its back each one of its thin and fragile ribs. Its appearance was also rather different from that of ordinary monkeys. It had large round eyes that were soft and timid; each socket had a black ring around it so that, in this regard, it resembled a panda bear. Its nose was long and pointy, with its delicate little mouth concealed beneath it. Protruding perpendicularly from its round head were two small dark oval ears. A fine layer of golden yellow down overlaid its brown fur. A black stripe ran along its spine from its neck to the tip of its barely discernible tiny tail. Its hands and feet, each with five long and lithe fingers and toes, were extremely human-like; a sheer round nail formed at the tip of each digit.

“I asked the peddler what kind of monkey it was. He called it a sleeve monkey, explaining that in ancient times people played with the monkey by tucking it up their sleeve. I also inquired about the monkey’s diet. The peddler replied that it eats fruit, adding that it also eats whatever humans eat. I asked about the monkey’s price, to which the peddler responded, “300.” He enumerated the price components: the original purchase price in Yunnan, the transportation cost and travel expenses, plus a small profit margin. We looked at the tiny fellow—ice-cold from head to toe, all skin and bones, on the verge of death, forlorn and helpless. We decided to buy it. We paid the peddler 270 yuan.

“After he settled into his new home we came up with a name for him, “Old Fool.” The name was meant to call attention, by contrast, to his daintiness and cleverness, and, as is customary with children from humble families, to shield him from jealous gods...“A few days later, the CCTV Midday News broadcast a story on the illegal sale of rare animals. The instant we saw the report, we both yelled, “Old Fool!” The report pictured two animals whose faces looked identical to Old Fool’s, but whose stature was larger. The broadcaster explained that recently in Guangzhou there were discovered two officially designated ‘critically endangered’ slow lorises that authorities suspected may have been abandoned following a failed attempt to smuggle them out of the country. We were stunned to discover that we were raising a nationally protected rare animal.

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see Old Fool: Elegy for a Monkey, MCLC Resource Center u.osu.edu/mclc/2017; See Separate Article LORISES factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: 1, 2, 3) Chinese Science Museum ; 4, 5) CBCF Primate info; 6) Animal info file; 7, 9) Kostich ; 8) CNTO, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025