LORISES

slender loris

Lorises are squirrel-size primates with large close-set eyes and movements that resemble those of a chameleon. Relatives of bush babies and lemurs, they live India and Asia and are nocturnal, eating insects, shoots, leaves, fruits with hard skin and birds' eggs.The name loris comes from the Dutch word for clown. [Source: K.A.I. Nekaris, Natural History, February 2002]

Whereas apes and monkeys are grouped as haplorhine or "dry nose" primates, lorises are strepsirrhine or "wet nose" primates. Lorises have big eyes, tiny ears, live in trees and are active at night. Lorises are a very old monkey species. They belong to the Lorisidae family, which includes nine genera, 18 species and 44 taxa and is divided into two subfamilies — Lorisinae (lorises) and Galaginare (galagos). They live in sub-Sahara Africa, India, Southeast Asia and Indonesia. All are small and nocturnal.

Loris eyes are eaten by some Indians who believe they are aphrodisiacs. Lorises are sometimes used by fortunetellers to pick cards with their long arms. They are also used in Ayuverdic medicine. The animal’s eyes are believed to be a potent love charm. Their bones are used to ward off the evil eye. In Sri Lanka some people fear the call of the loris and kill any of the animals they see. Sometimes they are killed while walking on power lines or are run over by vehicles. It is not known how many lorises there are.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SLENDER LORISES factsanddetails.com

GRAY SLENDER LORISES factsanddetails.com

SLOW LORISES factsanddetails.com

PYGMY SLOW LORISES factsanddetails.com ;

PRIMATES: HISTORY, TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com ;

MAMMALS: HAIR, CHARACTERISTICS, WARM-BLOODEDNESS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

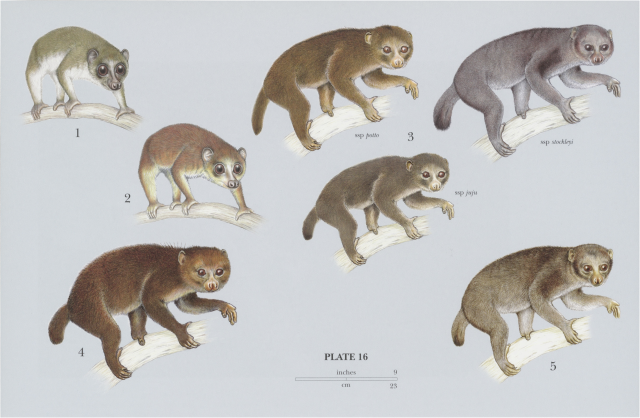

Loris Species

There are five to 25 species of loris in three genuses, with the species number depending on what is considered a species or subspecies. The two main types and names are slender lorises and slow lorises. The most common is the slender loris, which is native to southern India and Sri Lanka. Listed below is bold are the species recognized in the Wikipedia article. The others are recognized as subspecies

Genus Loris:

Gray slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus)

Highland slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus grandis)

Mysore slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus lydekkerianus)

Malabar slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus malabaricus)

Northern Ceylonese slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus nordicus)

Red slender loris (Loris tardigradus)

Dry Zone slender loris (Loris tardigradus tardigradus)

Horton Plains slender loris (Loris tardigradus nyctoceboides)

Genus Xanthonycticebus

Pygmy slow loris (Xanthonycticebus pygmaeus)

Genus Nycticebus

Bangka slow loris (Nycticebus bancanus)

Bengal slow loris (Nycticebus bengalensis)

Bornean slow loris (Nycticebus borneanus)

Sunda slow loris (Nycticebus coucang)

Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus)

Kayan River slow loris (Nycticebus kayan)

Philippine slow loris (Nycticebus menagensis)

Sumatran slow loris (Nycticebus hilleri)

Nycticebus linglom (fossil, Miocene)

Lorises and Lemurs

Lemurs and lorises are prosimians. By one definition a prosimian is a primate with a brain too small to qualify as a monkey. The prosimian classification is regarded as out of date. Scientists now use the classification Strepsirhini instead.

Ancient prosimians are believed to have originated in the Northern Hemisphere (North America or Europe) 65 million years ago. Many of the traits they developed — sterosciopic vision, grasping hands, large brains and superior muscular coordination and dexterity — grew out of the fact they lived in trees. The first primates appeared in the early Eocene period, which began 54 million years ago. It is widely believed that at around this time primates divided onto two major lineages: one that led to anthropoids and the other that led to modern prosimians.

Strepsirhini characteristics include procumbent lower incisors, a “grooming claw” on the second digit of the feet, a moist nose, and reflective layer behind the retina that aids night vision. Nearly three quarters of Strepsirhini are nocturnal. They rest during the day in nests or tree hollows. Adaption for nocturnal life include relatively large eyes; sensitive nocturnal division; large, independently movable ears; elaborate tactile hairs; a well developed sense of smell; and large olfactory bulbs. The social relations and communication methods used by nocturnal creature is very different than the diurnal ones. Most communicate with scent markings and vocalizations such as trills, “kiks” and whistles. Most are social only when the gather at sleeping sites. There they engage in behavior such as grooming. a characteristic of many primates.

Lorises and Pottos

pygmy slow loris

Pottos (Perodicticus potto) are slow-moving, nocturnal tropical African primates that live rainforest trees from Sierra Leone eastward to Uganda. The animals have a strong grip and cling tightly to branches, but when necessary they can also move quickly through the branches with smooth gliding movements that make them hard to detect. Pottos and lorises are probably closely related to galagos (bushbabies, the the Galagidae) and sometimes that family is considered to be a subfamily within the Lorisidae. If so, the terms Lorisinae and Galaginae are used for these groups. The fossil record of lorises and pottos extends back to the Early Miocene (23 million to 16 million years ago).

According to Animal Diversity Web: Lorises and pottos are small (85 grams — 1.5 kilograms), arboreal (live mainly in trees), primates of Africa and Asia. As of the early 2010s, six species placed in four genera made up the family (previously known as Loridae). In the wild they stealthily stalk insects or seek fruit at night and spending the day in hollow trees or clinging to branches. Lorises and pottos climb with deliberate, hand-over-hand movements, never leaping between branches. While their actions are usually slow and deliberate, they are capable of moving rapidly if necessary. The hands and feet of lorids are capable of powerful grasping, and these animals travel along the underside of branches as easily as along the top. Their tails are very short, seemingly absent in some species. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)] /=\

Lorises and pottos have thick, wooly fur, darker on the back than the venter. Their eyes are large and directed forward. They have strongly constructed skulls with well-defined temporal ridges. The braincase is rounded and the anterior (rostral) parts of the skull reduced. Their orbits are directed forward. Postorbital processes are present and wide, and the zygomatic arches are broad. The bullae are only moderately inflated, and the external auditory meatus is continuous with the zygomatic branch of the squamosal. The palate ends behind the last molar. /=\

The teeth of lorises and pottos are diverse and variously specialized. As in other strepsirhines, the lower incisors and canines form a comb-like structure. The most anterior lower premolars are canine-like. Upper canines are long and well-developed, and the molars have three or four cusps. The dental formula is 2/2, 1/1, 3/3, 3/3 = 36. /=\

The postcranial anatomy of lorises and pottos is also rather highly specialized. Their wrists appear modified for "armswinging" locomotion, similar to hominoids. Fore and hind limbs are approximately equal in length. On the feet, the big toe and thumb are well developed and strongly opposed to the remaining digits, more so than in the related galagos. All digits have nails except the second of the hind foot, which has a typical strepsirrhine " toilet claw." The arterial and venous circulation of the arms and legs is much subdivided to form networks of intertwining vessels (retia mirabilia), which facilitate the exchange of oxygen and waste materials and help the muscles remain contracted over long periods. /=\

Loris Characteristics

Lorises generally live until their mid teens. Their close-set eyes give them good stereoscopic vision. Their long, odd-looking arms allow them to move very quietly. According to Indian and Sri Lankan legend they move so quietly they are the only animals that can approach the peafowl, a bird that sleeps on the tops of trees, rear to rear, for protection from predators. In the legend the loris catches a peafowl it wrings its neck and eats it brains. The lifespan of lorises has not been widely researched. Slender lorises have a maximum lifespan of 16.4 years and Sunda slow lorises have a maximum lifespan of 26.5 years. Despite the high-sugar diet and small body mass of Sunda slow lorises, they have a very low metabolism. This may be due to a need to detoxify the toxic secondary compounds in their food matter.

Lorises appear lazy and slow. But don’t let appearances fool you. They are skilled hunters with extraordinary senses of sight, smell and hearing. Lorises feed almost exclusively on insects. They sneak up quietly on their prey and quickly grab it with their long, slender arm the same way a chameleon does with its tongue. They eat lots of locusts, occasionally eat slugs and are particularly fond of certain kinds of stinging ant and they cover themselves with their own urine as protection from the sting. Lorises and tarsiers are the only primates that eat mostly animal prey.

slow loris

David Attenborough wrote: “The loris's hands are remarkable. Its thumbs are greatly enlarged but the second finger, the index, is reduced to a small stub. This means that the span of its grasp is very wide, enabling it to get a firm grip on quite stout branches. Its feet are modified in a similar way though the second toe on each foot, while very small, carries a claw that the animal uses for cleaning its fur.” They “move through the branches slowly. Their method of hunting relies on this. Having spotted an insect it moves slowly towards it, while holding on firmly with its hind legs it lifts it hands and only at the last minute, makes a sudden lunge. They actively mark their territories by dragging their rumps on branches and also by depositing a few drops of urine.”

“The slender loris moves slowly and with great deliberation, seldom letting go with one limb unless its other three are firmly attached to something. And its grip is spectacular. If we grip something for more than a minute or so, our muscles tire and begin to ache. The loris, however, has a special mesh of blood vessels in its wrists and ankles that ensure that the muscles in its hands and feet are kept lavishly supplied with oxygen. As a result, the energy within the muscles is continually renewed and a loris can maintain a firm grip on a branch for 24 hours continuously. If you are by yourself, you will find it almost impossible to detach one from its branch if it is disinclined to leave. As fast as you remove one limb it will reattach itself with another.”

Loris Behavior

Most nocturnal primates live a solitary life, generally avoiding one other except for raising offspring. But this is not true with the slender loris. They generally hang out in pairs or small groups. They tend to gather outside the sleeping sites and groom each other, play and feed. Loris often sleep together on thorn trees for protection from predators such as fish owls, civets, jungle cats and house cats.

Females generally dominate males and dominant females are the most pronounced members of a loris community. They have access to the largest and most appetizing insects, chose when it is appropriate to groom and are strong enough to fend off unwanted advances by males. A typical group is made up of one or two adult males, one or two adult females, and two or three juveniles. Mature males often visit young unrelated female in the night.

Studies of Sunda slow lorises, a closely related species, suggest slow lorises maintain friendly relationships with members of their own species that share their home range, forming "spatial groups." It is unclear how they might benefit from these social groupings, as slow lorises rely on crypsis for protection from predators, do not assist others in finding food, and do not engage in alloparenting. [Source: Reyd Smith, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Loris Mating and Parenting

Female lorises reach sexual maturity at about age two and are capable of mating only a couple of days once or twice a year. The gestation period is about six months. About half the time twins are born. At other times a single infant in born. The demands of raising offspring usually limits the female from mating any more than about once a year.

Because the females don’t give birth all that often, the competition is fierce among males to mate with receptive females. Once their offspring are born the males share in the child rearing duties. Often the males most sought after by females hang around several females.

Loris copulate while hanging upside down from a branch. It is not known why they do this but in captivity if no branch is available they don’t mate. Lorises can copulate several times in a few hours and have sex for up to 15 minutes. While a couple is having sex there is often group of males hanging around, watching. Often there is a lot of hissing and growling between the male who is getting some and those that don’t. If a fight breaks out they are usually occur between two individuals and often can be quite nasty.

Young loris cling to their mothers the first few weeks of their life. After that mother the places them on a branch a while she forages. Reyd Smith wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Slow lorises practice ‘infant parking,’ where they leave their young hanging from a tree while they go off to feed. Infants are able to be parked on the day of birth. Young are covered in exudates from their mother's brachial gland in order to protect them from predators. If an infant calls to the mother while parked, the mother will immediately return. Slow loris mothers and their infants have a close attachment from the time of birth, sometimes continuing through their lifetimes. They carry their young on their backs for as long as three months after birth. They spend a large amount of time play-wrestling and socializing with their mothers as well as other adults once a few months old. Fathers are absent after copulation and do not contribute to parental care. Infants can be weaned at six months, but will continue nursing until they reach sexual maturity. [Source: Reyd Smith, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Story About a Loris Sold in a Chinese Market

Hu Fayun wrote: Old Fool is a tiny monkey. He’s not a kind of monkey we commonly see, but one that’s on the verge of extinction....Early last winter, my wife returned from the wet market and reported seeing a peddler selling two tiny monkeys; they were caged in a wire rattrap, curled up pitifully into little balls and huddled together to escape the cold. Each time my wife returned from the wet market she brought back a few of these heartrending stories: about a wounded muntjac deer with melancholy eyes; about a few small hedgehogs fighting fruitlessly to break free from a nylon net bag; about a row of brilliantly plumaged golden pheasant corpses; about a small squirrel struggling in the scorching sun for its final dying breath; about a clowder of cats crushed together and yowling piteously in chorus. There were also small squawking quail bouncing frenziedly in a basket, bare and bloody from being plucked featherless while alive. There were frogs, tortoises, soft-shelled turtles, and snakes—all of which, as recipes prescribe, had been skinned alive. There were also those docile and adorable pigeons, rabbits, and lambs. For these small creatures, every wet market is their Auschwitz concentration camp.[Source: "Old Fool: Elegy for a Monkey" by Hu Fayun, MCLC Resource Center, translated by Paul E. Festa, August 2017]

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see Old Fool: Elegy for a Monkey, MCLC Resource Center u.osu.edu/mclc/2017

Loris Clings to Underside of Car for 70 Kilometers

In 2004, AFP reported, a slender loris clung to the underside of a car on a 70-kilo meter journey in India, surviving with little more than sooty limbs. An animal rights group says the three-year-old monkey latched onto the chassis after the driver had braked to avoid running it over near Shetgere village west of Bangalore. [Source: AFP, March 2004]

The founding trustee of People for Animals, Alpana Bhartia said: "The driver assumed that the animal had been run over and checked underneath the car but found nothing," Bhartia said. "So he continued his journey to Bangalore. "The next day, a huge crowd had gathered in front of his house as they had found a loris amid the small plants in the car-parking area."

The car owner informed Bhartia's group, which took the monkey to a wildlife centre and plans to release it into the jungle this week. "It is a miracle that she survived," Bhartia said. "She is absolutely fine except for the black soot on the fore and hind limbs and excessive stress."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024