ROMAN HOUSES

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “When one thinks of Roman housing, images of the houses of Pompeii and Herculaneum typically come to mind. Exquisitely preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D., these architectural remains provide us with stunning insight into the domestic patterns of Romans in Italy in the first century A.D. However, the archaeological remains of the Roman empire are rich with domestic spaces, stretching from the western edge of Spain to the far eastern extremes of the empire....The Roman house was, as is true today, where the nuclear family lived. However, in addition to that, the household included servants for all members of the family. Many look for traces of servants within the remains of houses, but often the slaves slept in the doorways of their master's bedroom, or in rooms so simple that their functions cannot easily be reconstructed today. [Source: Ian Lockey, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “When one thinks of Roman housing, images of the houses of Pompeii and Herculaneum typically come to mind. Exquisitely preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D., these architectural remains provide us with stunning insight into the domestic patterns of Romans in Italy in the first century A.D. However, the archaeological remains of the Roman empire are rich with domestic spaces, stretching from the western edge of Spain to the far eastern extremes of the empire....The Roman house was, as is true today, where the nuclear family lived. However, in addition to that, the household included servants for all members of the family. Many look for traces of servants within the remains of houses, but often the slaves slept in the doorways of their master's bedroom, or in rooms so simple that their functions cannot easily be reconstructed today. [Source: Ian Lockey, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The term "Roman housing" can encompass many kinds of living spaces. Poorly built and maintained tower blocks in cities known as insulae housed the lower echelons of society in hazardous and overcrowded conditions. In the countryside, the poor lived in small villages or farms, in stone-built structures. The exploitation by the elite of hired and slave labor in agricultural endeavors and animal husbandry provides a more unusual category of Roman housing—rooms within industrial complexes such as olive oil factories, where a workforce lived during the production season. At the other extreme of the social scale, the elite had their impressive townhouses, and usually in addition their large villas or rural retreats with expansive floor plans, numerous entertainment spaces, and rich marble decoration, reflecting the importance for the elite of the domestic space for the creation of their public persona.” \^/

Mary Beard told Smithsonian magazine: Perhaps my favorite “little known fact” about Roman life is that when they wanted to talk about the size of a house, they didn't do it by floor area or number of rooms, but by the number of tiles it had on its roof! The magnificence of some of the great houses at Rome, even in Republican times, may be inferred from the prices paid for them. Cicero paid about $140,000, the consul Messala the same price, Clodius $600,000, the highest price known to us. All these were on the Palatine Hill, where ground, too, was expensive.

Many Roman and Greek homes, whether they belonged to rich city dwellers or poor farmers, were built around a courtyard. The openings of the house faced inward towards the courtyard rather than outward towards the street and other buildings. Families often lived in fairly cramped space with their slaves and servants, They often processed crops at home. Excavations of homes often reveal evidence of the threshing of cereals to make grains edible.

Vitruvius (80–70 to 15 B.C.), the famed military engineer and architect of the time of Caesar and Augustus, “says that the house should be suitable to the station of the owner, and that different styles of houses are appropriate in different parts of the world, according to the climate. At the same time it must be understood that the Roman house as we find it does not show as many distinct types as does the American house of the present time. The Roman was naturally conservative—he was particularly reluctant to introduce foreign ideas—and his house preserved in general certain main features essentially unchanged. The proportion of these might vary with the size and shape of the lot at the builder’s disposal, and the number of rooms added would depend upon the means and tastes of the owner, but the kernel, so to speak, was always the same. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

BUILDING MATERIALS IN ANCIENT ROME: CONCRETE, BRICKS AND MARBLE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROOMS AND PARTS OF AN ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSE factsanddetails.com ;

FEATURES OF ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSES: WALLS, DOORS, ROOFS, HEATING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FURNITURE IN ANCIENT ROME: BEDS, COUCHES, TABLES, CHAIRS, FRIDGES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN POSSESSIONS, TOOLS, KITCHEN STUFF, AND PERSONAL OBJECTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ARCHITECTURE: EMPERORS, ARCHES AND CONCRETE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Houses, Villas, and Palaces in the Roman World” by Alexander Gordon McKay (1975) Amazon.com;

“The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.- A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration” by by John R. Clarke Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Villas: The Essential Sourcebook” Ancient Roman Villas: The Essential Sourcebook” by Guy P. R. Métraux (2025) Amazon.com;

“Hadrian's Villa and Its Legacy” by William L. MacDonald, John A. Pinto (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Jane F. Gardner, Thomas Wiedemann Amazon.com;

“The Roman House and Social Identity” by Shelley Hales Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (1996) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in the Later Roman” by Kim Bowes, Richard Hodges Amazon.com;

“At Home in Roman Egypt: A Social Archaeology” by Anna Lucille Boozer (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Spread of the Roman Domus-Type in Gaul” by Lorinc Timar (2011) Amazon.com;

“Multisensory Living in Ancient Rome: Power and Space in Roman Houses”

by Hannah Platts Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins (1986) Amazon.com;

“Life in Ancient Rome: People & Places”, 450 Pictures, Maps And Artworks,

by Nigel Rodgers (2014) Amazon.com;

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Domus Versus Insula

In Rome, the urban poor tended to live in communal housing known as insula. Single-family houses known as domus were primarily for the wealthy and are at least the upper middle class and upwards. These large, comfortable dwellings were often big enough to accommodate the owner’s business, library, kitchen, pool, and garden. The oldest known domus dates to the end of the 4th century B.C. A major structural change was the introduction of the peristyle garden around the 2nd century B.C. Much of what is known about Roman houses comes from the study of dwelling at Pompeii.

The Roman domus turned a blind, unbroken wall to the street and all its doors and windows opened on its interior courts. The insula, on the other hand, opened always to the outside and when it formed a quadrilateral around a central courtyard, its doors, windows, and staircases opened both to the outside and to the inside. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The domus was composed of halls whose proportions were calculated once for all and dictated by custom in advance. These halls opened off each other in an invariable order : fauces, atrium, alae, triclinium, tablinum, and peristyle. The insula combined a number of cenacula, that is to say, distinct and separate dwellings like our "flats" or "apartments," consisting of rooms not assigned in advance to any particular function. The plan of each story was apt to be identical with that above and below, the rooms being superimposed from top to bottom of the building. The domus, influenced by Hellenistic architecture, spread horizontally, while the insula, begotten probably in the course of the fourth century B.C. of the necessity of housing a growing population within the so-called Servian Walls, inevitably developed in a vertical direction.

In contrast to the Pompeian domus, the Roman insula grew steadily in stature until under the Empire it reached a dizzy height. Height was its dominant characteristic and this height which once amazed the ancient world still astounds us by its striking resemblance to our own most daring and modern buildings. As early as the third century B.C. insulae of three stories (tabulata, contabidationes, contignationes) were so frequent that they had ceased to excite remark. In enumerating the prodigies which, in the winter of 218-217 B.C., preluded the invasion of Hannibal, Livy mentions without further comment the incident of an ox which escaped from the cattle market and scaled the stairs of a riverside insula to fling itself into the void from the third story amid the horrified cries of the onlookers. By the end of the republic the average height of the insulae indicated by this anecdote had already been exceeded.

Insulae

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “One’s neighborhood pretty much depended on how high up the totem pole you were. Insulae were apartment buildings, but the kind that would make a modern safety inspector hit the roof. The majority of the Roman population lived in these seven-story-plus buildings. They were ripe for fire, collapse, and even flooding. The upper floors were reserved for the poor who had to pay rent daily or weekly. “Eviction was a constant fear for the families living in a one-room affair with no natural light or bathroom facilities. The first two floors of an insulae were reserved for those who had a better income. They paid rent annually and lived in multiple rooms with windows.” [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016]

Pompeii street

Before the end of the Republic, in Rome and other cities only the wealthy could afford to live in private houses. By far the greater part of the city population lived in apartment buildings and tenement houses. These were called insulae, a name originally applied to city blocks. They were sometimes six or seven stories high. Augustus limited their height to seventy feet; Nero, after the great fire of his reign, set a limit of sixty feet. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“They were frequently built poorly and cheaply for speculative purposes; and Juvenal speaks of the great danger of fire and collapse. Except for the lack of glass in the windows they must have looked rather like modern buildings of the sort. Outside rooms were lighted by windows. There were sometimes balconies overhanging the street. These, like the windows, could be closed by wooden shutters. The inner rooms were lighted by courts if, indeed, they were lighted at all. |+|

“The insulae were sometimes divided into apartments of several rooms, but were frequently let by single rooms. At Ostia remains of insulae have been found in which each of the upper apartments has its own stairway. The ground floors were regularly occupied by shops. The superintendent of the building, who looked after it and collected the rents, was a slave of the owner and was called the insularius.”|+|

Materials Uses to Make Roman Houses

Houses were usually built of sun-dried brick on a stone foundation. The roofs were often flat and were sometimes covered with hardened mud, but tile roofs were also common. Marble for columns and other decorative features was introduced into Rome in the later part of the Republican period and colored marbles were used freely by the rich Romans of the Empire. Walls were covered with stucco, which was frequently painted. There was no wall-paper, of course, and pictures were painted directly on the walls. Fashions in decoration changed as they do at present, though more slowly. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Roman bricks were long and thin, much larger than modern bricks, requiring approximately six courses for a 30 centimeters wall-height, but this varies. Floors in early times were of hardened earth, paving stones, or plaster. In the fifth century pebbles set in cement came into use in Greece, and from this kind of floor mosaic, plain and patterned, was derived. Pictures or decorative designs made of fine glass mosaic were also used as wall decorations.

Roman House Design: Public vs. Private, Open vs. Closed

Roman architecture was oriented towards practical purposes and creating interior spaces. Roman buildings looked heavy on the outside. One of the main goals was to create large interior spaces.

Roman house design has been described a balance of enclosed versus open spaces, or public versus private spaces. Andrew Wallace-Hadrill of the University of Reading has argued that Roman houses are not private spaces as defined in opposition to public spaces, but rather private spaces within public spaces serving their interests. He argues that it makes sense that members of the elite engaged in public life would more likely need more public areas in their home, while people of humbler origin need more privacy. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “While modern-day houses often function as more of an escape from the pressures of the public world, opened generally only to friends, in the Roman world, the house of an elite was both a private retreat and a center for business transactions. As a result of this public function, decoration and architectural elaboration were of especial importance and the collection of Roman art at the Metropolitan Museum reflects this elite domestic adornment.’” [Source: Ian Lockey, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org]

Development of the Roman House

Early Roman huts

Ancient houses, for the most part, were made of sun dried bricks placed on a stone foundation, like dwelling in the modern developing world. The walls and roofs were probably supported and reinforced by timbers and beams, but we can't say for sure because wood and mud bricks decompose rapidly, which is also why there are hardly ever any houses at archaeological sites. Generally only temples and monuments were built of marble and stone. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum ||]

The primitive Roman house goes back to the simple farm life of early times, when all members of the household, father, mother, children, and dependents, lived in one large room together. In this room (atrium) the meals were cooked, the table spread, all indoor work done, and the sacrifices offered to the Lares; at night a space was cleared in which to spread the hard beds or pallets. The primitive house had no chimney; the smoke escaped through a hole in the roof. There were no windows; all natural light came through the hole in the roof. There was but one door; the space opposite it seems to have been reserved as much as possible for the father and mother. Here was the hearth, where the mother prepared the meals, and near it stood the implements she used in spinning and weaving; here was the strong box (arca) in which the master kept his valuables, and here the bed was spread. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The earliest house was a round or oval hut with thatched roof such as was reproduced in the traditional hut of Romulus on the Palatine.1 The round shape was retained in the form assigned to the Temple of Vesta, whose worship began at the hearth in such huts. The later huts were oval. Later still came a rectangular form. The outward appearance of such a hut is shown in the Etruscan cinerary urns, found in various places in Italy. The ground plan was a simple rectangle without partitions. This may be regarded as historically and architecturally the kernel of the Roman house. Its very name (atrium), which originally denoted the whole house, was also preserved; it appears in the names of certain very ancient buildings in Rome used for religious purposes, the Atrium Vestae, the Atrium Libertatis, etc. In later times, however, atrium was applied to a single characteristic room of the house. The origin of the name atrium is still a mystery, The funerary urn from Chiusi, often illustrated, has a square opening in the top. This has been taken to show that the early house of the rectangular type had such an opening in the middle of the roof for the escape of smoke. It has been shown, however, that this particular urn has lost the top-piece that completed its roof. Urns of this type have regularly one door, and occasionally windows. |+|

“A feature of the later house, so commonly found in connection with the atrium that one is tempted to suppose it an early addition, is the tablinum, the wide recess opposite the entrance door. The origin of the tablinum, and the uses to which it was put, alike in earlier and in later times, are still matters of dispute. It may have been intended at first for merely temporary purposes, being built of boards (tabulae), and having an outside door and no connection with the atrium. It could not have been long, however, until the wall between was broken through. When this was once done and its convenience demonstrated, the partition wall was removed. Varro explained the tablinum as having been a sort of balcony or porch, used as a dining-room in hot weather. |+|

“Later, the atrium received its light from a central opening in the roof, the compluvium,2 which derived its name from the fact that rain, as well as air and light, could enter here. Just beneath this a basin, the impluvium, was hollowed out in the floor to catch the water for domestic purposes. As more space and privacy were demanded, the house was enlarged by small rooms opening out of the atrium at the sides. The atrium at the end next the tablinum had the full width between the outside walls, and the additional spaces, or alcoves, one on each side, were called alae. The appearance of such a house as seen from the entrance door must have been much like that of an Anglican or Roman Catholic church. The atrium corresponded to the nave, the two alae to the transepts, while the bay-like tablinum resembled the chancel. So far as we know, the outside rooms received light only from the atrium. From this ancient house we find preserved in its successors all that was opposite the entrance door, the atrium with its alae and tablinum, the impluvium and compluvium. These are the characteristic features of the Roman house, and must be so regarded in the description which follows of later developments under foreign influence. |+|

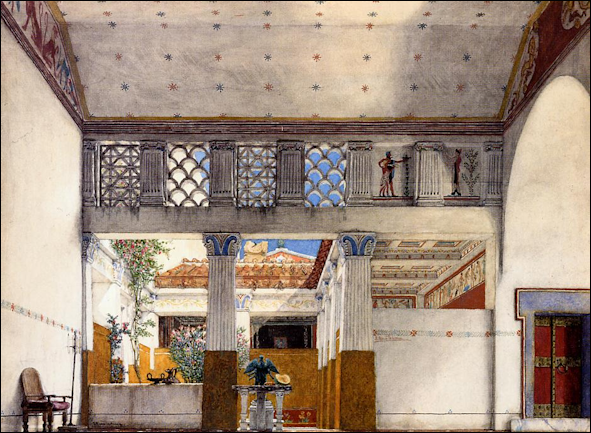

Coriolanus House by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

“The Greeks seem to have furnished the idea next adopted by the Romans, a court at the rear of the tablinum, open to the sky, surrounded by rooms, and set with flowers, trees, and shrubs. The original house is combined with the peristyliumThe open space had columns around it and often a fountain in the middle. This court was called the peristylium or peristylum. According to Vitruvius its breadth should exceed its depth by one-third, but we do not find these or any other proportions strictly observed in the houses that are known to us. Access to the peristylium from the atrium could be had through the tablinum, though this might be cut off from it by folding doors, and by a narrow passage (andron) at one side. The latter would naturally be used by slaves and by others when they were not privileged to pass through the tablinum. Both passage and tablinum might be closed on the side of the atrium by portières. The arrangement of the various rooms around the peristylium seems to have varied with the notions of builder or owner; no one plan for them can be laid down. According to the means of the owner there were bedrooms, dining-rooms, libraries, drawing-rooms, kitchen, scullery, closets, private baths, together with the simple accommodations necessary for a varying number of slaves. But, whether these rooms were many or few, they all faced the court, receiving from it light and air, as did the rooms along the sides of the atrium. There was often a garden behind the peristylium. |+|

“The next change took place in the city and town house only, because it was due to conditions of town life that did not obtain in the country. In ancient as well as in modern times business was likely to spread from the center of the town into residence districts, and it often became desirable for the owner of a dwelling house to adapt it to the new conditions. This was easily done in the case of the Roman house on account of the arrangement of the rooms. Attention has already been called to the fact that the rooms all opened to the interior of the house, that few windows were placed in the outer walls, and that there was frequently only one door, and that in front. If the house faced a business street, it is evident that the owner could, without interfering with the privacy of his house or decreasing its light, build rooms in front of the atrium for commercial purposes. He reserved, of course, a passageway to his own door, narrower or wider according to the circumstances. If the house occupied a corner, such rooms might be added on the side as well as in the front, and, as they had no necessary connection with the interior, they might be rented as living-rooms, as separate rooms often are in our own cities. It is probable that rooms were first added in this way for business purposes by an owner who expected to carry on some enterprise of his own in them, but even men of good position and considerable means did not hesitate to add to their incomes by renting to others these disconnected parts of their houses. All the larger houses uncovered in Pompeii are arranged in this manner. One occupying a whole block and having rented rooms on three sides. Such a detached house was called an insula.” |+|

Construction of a Roman House

Hadrian's Villa The buildings of Rome were far too lightly built. While the domtis of Pompeii easily covered 800 to 900 square meters, the insulae of Ostia, though built according to the specifications which Hadrian laid down, were rarely granted such extensive foundations. As for the Roman insulae, the ground plans recoverable from the cadastral survey of Septimius Severus, who reproduced them, show that they usually varied between 300 and 400 square meters. Even if there were no smaller ones (which is extremely unlikely) of which all trace has been buried for ever in the upheavals of the terrain, these figures are misleading: a foundation of 300 square meters is inadequate enough to carry a structure of 18 to 20 meters high, particularly when we remember the thickness of the flooring which separated the stories from each other. We need only consider the ratio of the two figures given to feel the danger inherent in their disproportion. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The lofty Roman buildings possessed no base corresponding to their height and a collapse was all the more to be feared since the builders, lured by greed of gain, tended to economise more and more at the expense of the strength of the masonry and quality of the materials.Vitruvius ( states that the law forbade a greater thickness for the outside walls than a foot and a half, and in order to economise space the other walls were not to exceed that. He adds that, at least from the time of Augustus, it was the custom to correct this thinness of the walls by inserting chains of bricks to strengthen the concrete. He observes with smiling philosophy that this blend of stone-course, chains of brick and layers of concrete in which the stones and pebbles were symmetrically embedded, permitted the convenient construction of buildings of great height and allowed the Roman people to create handsome dwellings for themselves with little difficulty: "populus romanus egregias habet sine impeditione habitationes." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Twenty years later Vitruvius would have recanted. The elegance he so admired had been attained only at the sacrifice of solidity. Even after the brick technique had been perfected in the second century, and it had become usual to cover the entire facade with bricks, the city was constantly filled with the noise of buildings collapsing or being torn down to prevent it; and the tenants of an insula lived in constant expectation of its coming down on their heads. We may recall the savage and gloomy tirade of Juvenal: "Who at cool Praeneste, or at Volsinii amid its leafy hills, was ever afraid of his house tumbling down?... But here we inhabit a city propped up for the most part by slats : for that is how the landlord patches up the crack in the old wall, bidding the inmates sleep at ease under the ruin that hangs above their heads." The satirist has not exaggerated and many specific cases provided for in the legal code, the Digest, take for granted precisely the precarious state of affairs which excited Juvenal's wrath.

Houses at Pompeii

Casa Di Octavio Pompeii houses are usually named after prominent paintings or sculptures or other artefacts. The House of the Surgeon is so no named, for example, because a bunch of doctor instruments were found there. The House of Chaste Lovers features a fresco of, yes, chaste lovers. Many frescoes can be viewed at Pompeii. It is worth wandering around aimlessly for a while on your and checking out the frescoes in the villas off the main tourist circuit.

The House of Faun (nearby on V. della Fortuna) is named after a bronze of a dancing faun that was found here along with a large floor mosaic that reads Have (Welcome). The famous Alexander the Great mosaic was also found here. Near the House of Faun off of V. della Fortuna are the House of the Labyrinth, the House of the Ancient Hunt and an ancient bakery.

The House of the Vetti (on V. della Fortuna) is one of the most popular villas at Pompeii. The Ixon Room in the villa looks a small art gallery. There are delightful murals with cherubs performing tasks like forging, goldsmithing and making weapons. The biggest draw are the erotic frescoes and statues. A fresco beside the entrance to the villa shows the god of fertility Priapus, whose penis is so large it is held up by a string. Off in a side room to the right of the Priapus entrance is statue of Priapus with his penis erect and erotic frescoes of couples having sexual intercourse sitting down and in other positions.

In Roman times, rooms with erotic art were generally only for men and their concubines. This was also true in modern times until recently when the frescoes used to be shown only to men tourists. Women and children needed to bribe a guard to get let in. In the early 1800s, the outcry over the finding of erotic art at Pompeii led to the "excommunication" of Pompeii. House Marcus Lucretius Fronto (several blocks east of the House of Vetti) features a garden mural that depicts a hunt scene with bears, boars, and snakes in addition to a lion attacking a bull and a tiger pursuing a deer.

The House of Chaste Lovers was opened the late 2000s. It is named after a fresco of a couple in a gentle embrace. In antiquity the house was both a residence and a commercial enterprise for a wealthy entrepreneur. A bakery has been identified by the presence of ovens. Pollen analysis revalued that reed trellises separated geometrically-shaped beds of roses, juniper and ferns. The triclinium (dining room) was painted with banqueting scenes, including the lovers. A depiction of a drinking game in The House of Chaste Lovers in Pompeii shows one person still drinking while another is slumped over a couch, defeated.

The House of the Moralist at Pompeii is so named because the owner wrote rules of etiquette for his neighbors and visitors on the walls of his house, including “Let water wash your feet clean” and “Take care of our linens." The House of the Tragic Poet (on Via dell'Abbondanza near the Amphitheater) features a fine entrance mosaic with a snarling dog and a sign that says "Cave Canem" (“Beware of the dog”). The House of Venus (on Via dell'Abbondanza near the Amphitheater) features wonderful frescoes and modern gardens planted like Roman gardens.

The Villa of Mysteries (outside of Pompeii) is regarded as the best preserved villa from the ancient world. The best-preserved frescoes show a bride's initiation into the forbidden cult of Dionysus. The magnificent work of art features satyrs and Silenis honoring Dionysus and naked, flute-playing little girls entertaining a young man and a demon hiding in the closet. The magnificent painting is alive with color. There is also a checkered tile floor and layers of colored marble underneath the painting. The villa is often roped and a separate admission has to be paid to get in.

See Separate Article:

POMPEII VILLAS europe.factsanddetails.com

Country Houses in the Roman Era

Country estates might be of two classes, countryseats for pleasure and farms for profit. In the first case the location of the house (villa urbana, or pseudourbana), the arrangement of the rooms and the courts, their number and decoration, would depend entirely upon the taste and means of the master. Remains of such houses in most varied styles and plans have been found in various parts of the Roman world, and accounts of others in more or less detail have come down to us in literature, particularly the descriptions of two of his villas given by Pliny the Younger. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Some villas were set in the hills for coolness, and some near the water. In the latter case rooms might be built overhanging the water, and at Baiae, the fashionable seaside resort, villas were actually built on piles so as to extend from the shore out over the sea. Cicero, who did not consider himself a rich man, had at least six villas in different localities. The number is less surprising when one remembers that there were nowhere the seaside or mountain hotels so common now, so that it was necessary to stay in a private house, one’s own or another’s, when one sought to escape from the city for change or rest. |+|

“Vitruvius says that in the country house the peristyle usually came next the front door. Next was the atrium, surrounded by colonnades opening on the palaestra and walks. Such houses were equipped with rooms of all sorts for all occasions and seasons, with baths, libraries, covered walks, gardens, everything that could make for convenience or pleasure. Rooms and colonnades for use in hot weather faced the north; those for winter were planned to catch the sun. Attractive views were taken into account in arranging the rooms and their windows. |+|

Roman Villas

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The villa holds a central place in the history of Western architecture. On the Italian peninsula in antiquity, and again during the Renaissance, the idea of a house built away from the city in a natural setting captured the imagination of wealthy patrons and architects. While the form of these structures changed over time and their location moved to suburban or even urban houses in garden settings, the core design tenet remained an architectural expression of an idyllic setting for learned pursuits and spiritual withdrawal into a domestic retreat from the city. After the Renaissance, the villa appears beyond an Italian context as an architectural form revived and reimagined throughout western Europe and in other parts of the world influenced by European culture. [Source: Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, Independent Scholar, Geoffrey Taylor, Department of Drawings and Prints, Metropolitan of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The term villa designates several types of structure that share a natural setting or agrarian purpose. Included in the architecture of a villa may be working structures devoted to farming, referred to as villa rustica, as well as living quarters, or villa urbana. The villa is therefore most aptly understood as a label or identity capturing several distinct parts, sometimes interrelated or dependent on one another and in other cases divorced from a larger architectural complex. Rather than embodying a concrete form, the term villa exhibits mobility as the application of an idea to architecture. In place of a fixed image is an architectural environment that embodies an ideal of living, or villeggiatura. \^/

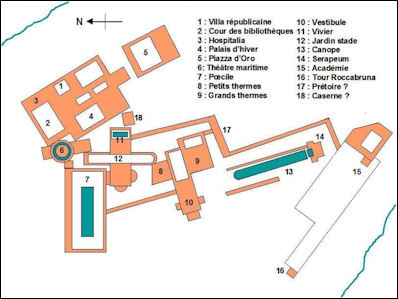

Hadrian Villa map“The form and organization of villa architecture depend upon literary descriptions provided by the authors of ancient Rome. Particularly, the writings of Columella (4–70 A.D.) in De re rustica and Cato (234–149 B.C.) in De agricultura elaborate on the features of their villas in the Campagna, the low-lying area surrounding Rome. Common among ancient writings, the villa enjoys from the natural setting restorative powers, or otium, in opposition to the excesses of city life, or negotium. Horace (65–8 B.C.) extolled the simple virtues and pleasures of ancient villa life in his poetry (for example, Odes I.17, Epistles I.7 and 10). \^/

“However, Pliny the Younger (ca. 61–112), in his Letters (Epistle to Gallus 2.17; Epistle to Apollinaris 5.6), persuaded later patrons and architects of the beauty afforded by his Laurentine and Tuscan villas. His descriptions constructed images of the general appearance of the villas and unfolded the experience with intertwined interior and exterior architectural features. Pliny's retreats slipped into the landscape with terraced gardens and opened outward to natural surroundings through colonnades, or loggias, which replaced solid enclosing walls. The author retired to the gardens, or horti, to appreciate the abundance of flora and fauna. The cultural life of poetry, art, and letters unfurled in a setting that was distinctly different from the urban experience of Rome. Relying on initial reconstructions by Vincenzo Scamozzi (1552–1616), later architects would turn to Pliny's descriptions to imagine the spaces and experience of the ancient villa. \^/

Tivoli and Hadrian’s Villa

Tivoli (25 kilometers northeast of Rome) is the home of Villa Adriana, a huge sprawling villa built by the Roman Emperor Hadrian. Completed after 10 years of work, Tivoli contains 25 buildings built on 300 acres of land, including an elaborate bath house fed by water piped in from the Apennines. The buildings are now ruins. Tivoli has been a popular retreat since Roman times. It embraces the ruins of several magnificent villas including Villa Adriana, a lavish complex built by Emperor Hadrian, and Villa d' Este, known for its lavish gardens and plentiful cascading fountains. A pool at the banquet hall is surrounded by columns and statues of gods and caryatids.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The architecture and landscape elements described by Pliny the Younger appear as part of the Roman tradition of the monumental Villa Adriana. Originally built by Emperor Hadrian in the first century A.D. (120s–130s), the villa extends across an area of more than 300 acres as a villa-estate combining the functions of imperial rule (negotium) and courtly leisure (otium).” [Source: Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, Independent Scholar, Geoffrey Taylor, Department of Drawings and Prints, Metropolitan of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

part of Hadrian's villa

Hadrian's villa was completed in A.D. 135. The temples, gardens and theaters are full of tributes to classical Greece. Historian Daniel Boorstin it "still charm the tourist. The original country palace, stretching a full mile, displayed his experimental fantasy. There, on the shores of artificial lakes and on gently rolling hills groups of buildings celebrated Hadrian's travels in the styles of famous cities he had visited with replicas of the best he had seen. The versatile charms of the Roman baths complemented ample guest quarters, libraries, terraces, shops, museums, casinos, meeting room, and endless garden walks. There were three theaters, a stadium, an academy, and some large buildings whose function we cannot fathom. Here was a country version of Nero's Golden House."

Villa Adriana is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. According to UNESCO: “The Villa Adriana (at Tivoli, near Rome) is an exceptional complex of classical buildings created in the 2nd century A.D. by the Roman emperor Hadrian. It combines the best elements of the architectural heritage of Egypt, Greece and Rome in the form of an 'ideal city'. The Villa Adriana is a masterpiece that uniquely brings together the highest expressions of the material cultures of the ancient Mediterranean world. 2) Study of the monuments that make up the Villa Adriana played a crucial role in the rediscovery of the elements of classical architecture by the architects of the Renaissance and the Baroque period. It also profoundly influenced many 19th and 20th century architects and designers. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website]

One of the most interesting features in the Vatican's Egyptians Museum is a the recreation of an Egyptian-style room found in the palace of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. Among the many Egyptian-style Roman pieces here is a Pharaoh-like rendering of Hadrian's male lover Antinoüs.

See Separate Article: HADRIAN'S BUILDING PROJECTS, TOURS AND DEFENSES europe.factsanddetails.com

Villa at Boscotrecase

Le nymphee of Hadrian's Villa

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In antiquity, numerous Roman villas dotted the coast along the Bay of Naples. One of the most sumptuous must have been the villa at Boscotrecase built by Agrippa, friend of Emperor Augustus and husband of his daughter Julia. In 11 B.C., the year after Agrippa's death, the villa passed into the hands of his posthumously born infant son, Agrippa Postumus. As the child was only a few months old, Julia would have overseen the completion of the villa. The frescoes, which are among the finest existing examples of Roman wall painting, must have been painted during renovations begun at that time. Most of the panels feature delicate ornamental vignettes and landscapes with genre and mythological scenes set against richly colored backgrounds. On the basis of their remarkable similarity to paintings in the Villa Farnesina in Rome, the Boscotrecase frescoes most likely were executed by artists from the capital city. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The frescoes from Boscotrecase are masterpieces of the Third Style of Roman wall painting, which flourished during the reign of Augustus. While earlier artists focused on creating an illusion of architectural depth with solid architectural forms, the artists at Boscotrecase presented the idea with whimsical, attenuated, and highly refined elements. At Boscotrecase, spindly canopies rest on improbably thin columns that seem to be made of alternating vegetal and metal drums. These almost weightless columns embellished with jewel-like decorations support pavilions, candelabra, and tripods. Other frescoes from the villa depict mythological scenes and Egyptianizing panels, ensembles that are at once colorful and complex. The occupants and those who visited the villa at Boscotrecase were not greeted by grand vistas of architectural splendor, but by slender, elegant, and especially decorative architectural forms, playfully alluding to contemporary cultural and political concerns. \^/

The wall-paintings from a villa near Boscoreale, in the Eighth Room, illustrate several types in use in Italy in the first century A.D. The earliest style imitated columns, marble panels, or other ornamental features employed in buildings. Arabesques and fanciful combinations of foliage, birds, animals, and masks came into use later. Mythological and genre scenes, as the lady with the kithara and the group of a man and a woman seated side by side, required a skilful painter and were naturally reserved for the principal rooms. In the cubiculum another style has been employed, in which buildings, arches, porticoes, and gardens are combined in a way which, while of course somewhat fanciful, still probably represents the general appearance of the streets and houses of Pompeii and other cities of the time. Stucco reliefs, of which there are several graceful examples in the Museum, were used in Greek houses of the Hellenistic period as well as in Italy. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Romans Villas Resurrected in Renaissance Italy

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Fallen into ruin, the vast archaeological site” that included Hadrian’s Villa “was recovered in the fifteenth century and many architects—including Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439–1501), Andrea Palladio (1508–1580), and Pirro Ligorio (ca. 1510–1583)—excavated and recorded firsthand the details of Hadrian's design while consulting descriptive passages of the emperor's life at the villa from the text Historia Augusta. Most notably, the architect-antiquarian Ligorio employed sculptural remains of the Villa Adriana in the Vatican gardens and as architectural spolia in his design of the nearby Villa d'Este (begun 1560). Built as one of the most splendid garden ensembles in Renaissance Italy, Ligorio's design for Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este (1509–1572) remains celebrated for its festive waterworks and terraced gardens. Like the descriptions of ancient villas consulted by Renaissance architects, the Villa d'Este commands spectacular vistas over the Roman campagna from its position high in the hills of Tivoli above the Villa Adriana. [Source: Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, Independent Scholar, Geoffrey Taylor, Department of Drawings and Prints, Metropolitan of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The imagined grandeur of the ancient Roman villa-estate depended not only on written descriptions but developed from the rediscovery of painted frescoes on the walls of antique ruins. The painter-architect Raphael (1483–1520) and his workshop reinterpreted the highly ornamental stucco details from their archaeological studies for the monumental Villa Madama in Rome (begun 1517). The painted and sculpted relief grotesques portray narratives from ancient authors and follow antique examples from the Villa Adriana and the Domus Aurea. Similarly, for Pope Julius III del Monte, several architects—including Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (1507–1573), Bartolomeo Ammanati (1511–1592), and Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574)—created ornate surfaces within the courtyard, loggia, and grotto at the retreat in suburban Rome known as the Villa Giulia (1551–53). \^/

“Inspired by ancient precedent, Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola adapted an enormous pentagonal-shaped fortified structure in his design for the Villa Farnese (begun 1556), which integrated the concepts of the Roman garden and villa within an invented form featuring a circular courtyard. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, as the Roman elite looked to build country retreats, other architects began to specialize in villa architecture with increasing latitude from historical examples. Skillfully blending principles of classical form with the Baroque ideas of unity, grandeur, and the spectacular, their designs unified the architecture of the surface, interior, and landscape setting into a carefully arranged decorative whole. \^/

“Beautiful ornamental facades, elaborate entrance gates, and gardens, replete with fantastic water displays and antique statues, formed the stage for the grand theatrical entertainments of the day. Noteworthy examples include the immense villa gardens on the Pincio and Gianiculum hills associated with the powerful families of Rome such as the Villa Pincian (now Villa Borghese, 1612–13), the Villa Medici (1540/1574–77), and the Villa Doria Pamphilj (1644–52) on the Gianiculum. Equally vast estates were laid out in the Alban hills outside Rome at Frascati, including the Villa Aldobrandini (1598–1603) and the Villa Mondragone (1573–77). In and around Florence during the sixteenth century, the Medici family developed a series of villas integrated with the garden setting, such as the magnificently situated Villa Medici at Fiesole (1458–61), the inventive villa-park at Pratolino (now Villa Demidoff, 1569–81), and the delightful Villa La Petraia (1575–90), with its central belvedere overlooking the Arno River valley. \^/

Getty Villa museum based on the Villa de Papyri at Herculaneum

“A variation of the Roman villa ideal developed on the mainland, or terra firma, of the Venetian republic in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The result of noble families improving their estates, the villa designs in the Veneto responded to Renaissance ideas promoted by humanist scholars and illustrated in the pages of architectural treatises printed in Venice by Italy's most prolific presses. The 1511 edition of Vitruvius' De architectura, prepared by the Franciscan friar and architect Giovanni Giocondo da Verona (ca. 1433–1515), added woodblock images of ancient buildings to visually describe the notoriously difficult first-century B.C. text. With nearly equal importance given to words and images, Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554) amended ancient models with contemporary Roman examples on the pages of Regole generali di architettura (1537) and Il terzo libro, de le Antiquita (1540), the first two published books of his multivolume treatise.” \^/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024