HADRIAN (A.D. 117-138)

18th century bust of Hadrian

Hadrian (born A.D. 76, ruled A.D. 117-138) was the emperor of Rome during the golden age of the Roman Empire. He distinguished himself as a visionary leader, military strategist, poet, artist and architect. He and Trajan oversaw an exceptional period of peace and prosperity. He protected Roman citizens from hostile tribes in Scotland by overseeing the construction of Hadrian's Wall and made peace in Mesopotamia by pulling back from the Euphrates and making peace with the Parthians. Hadrian also designed several monuments in Rome and may have even been the chief architect of the Pantheon.

Hadrian, whose full name was Publius Aelius Hadrianus, was Trajan's adopted heir. He was born in Rome but, like Trajan, grew up in Spain. Hadrian is famous for his stunning accomplishments in Rome and Athens, but his personality is a puzzle. Tom Dyckoff wrote in The Times: “He was both an imperial paper-pusher of the most anally retentive kind – infamous for controversially ditching his predecessors’ policies of war and expansion in favour of a slightly unsexy combination of peace, consolidating territory and increasing administrative efficiency – and an aesthete, perhaps the most erudite, sensitive and sophisticated of all Roman emperors, well versed in poetry and painting, and a virtuoso in his greatest love of all – architecture. Hadrian’s historical detractors claim that so bitter was he at Trajan’s posthumous reputation he had Apollodorus killed after the architect mocked one of Hadrian’s own designs. All myth, alas – indeed, one of the first acts Hadrian undertook as emperor was to honour Trajan and his sister with temples. Under his patronage, vast swaths of the city were restored. [Source: Tom Dyckoff, the Times, July 2008]

Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: “A cultured scholar, fond of all things Greek, Hadrian travelled all over the empire. He was attentive to the army and the provincials, and left behind him spectacular buildings such as the Pantheon in Rome and his villa at Tivoli. But his greatest legacy to the empire was his establishment of its frontiers, marking a halt to imperial expansion. He was truly a pivotal emperor, in that he divided what was Roman from what was not. Apart from minor adjustments, no succeeding emperor reversed his policies. [Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

HADRIAN (RULED A.D. 117-138): HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND REIGN AS EMPEROR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FIVE GOOD EMPERORS: ADOPTIONS, NERVA AND ANTONINE DYNASTY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TRAJAN (RULED A.D. 98-117): HIS CONQUESTS, TRAJAN'S COLUMN, AND LETTERS ABOUT HOW HE GOVERNED europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MARCUS AURELIUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Hadrian and the Cities of the Roman Empire”by Mary Taliaferro Boatwright (2002) Amazon.com;

“Hadrian and the City of Rome” by Mary Taliaferro Boatwright Amazon.com;

“The Pantheon: Design, Meaning, and Progeny”, Illustrated, by William L. MacDonald (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Pantheon” Reprint Edition by Tod A. Marder Amazon.com;

“Hadrian's Villa and Its Legacy” by William L. MacDonald, John A. Pinto (1997) Amazon.com;

“Hadrian's Wall AD 122-410" by Nic Fields, Donato Spedaliere (Illustrator) (2003) Amazon.com;

“Memoirs of Hadrian” by Marguerite Yourcenar (1951) Amazon.com

“Beloved and God: The Story of Hadrian and Antinous” by Royston Lambert (1996) Amazon.com;

“Hadrian: Empire and Conflict” by Thorsten Opper (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Triumph of Empire: The Roman World from Hadrian to Constantine” by Michael Kulikowski (2016) Amazon.com;

Roman Construction in Italy from Nerva Through the Antonines” by Marion Elizabeth Blake (1973) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C. - A.D. 476" by Michael Grant (1997) Amazon.com;

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World”

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Hadrian, the Master Builder

Hadrian was well known for building monuments across the Roman Empire, which was at its largest when he was emperor. Hadrian’s Wall in Britain “and a host of other monuments, attest to his taste, activity, and power.” Tom Dyckoff wrote in The Times: Hs monuments include "the Pantheon, that Temple of the Divine Trajan, the vast Temple of Venus and Roma, the only building for certain designed by Hadrian, his country estate at Tivoli and, to cap it all, his mausoleum – its ruins now assimilated into Rome’s Castel Sant’ Angelo. His wall in northern England was no exception, either. In the provinces, Hadrian bolstered defences, improved cities and built temples, along the way revolutionising the construction industry and securing jobs and prosperity for the plebs. Hail Hadrian, patron saint of hod-carriers. [Source: Tom Dyckoff, the Times, July 2008 ==]

“Hadrian’s architectural passions were the high point of the “Roman Architectural Revolution”, 200 years during which a genuinely Roman language of architecture emerged after several centuries of slavish copying of the Ancient Greek originals. At first the use of such novel materials as concrete and a newly rigid lime mortar was driven by the empire’s expansion, and the consequent demand for new large, practical structures – warehouses, record offices, proto-shopping arcades – easily and quickly put up by unskilled labour. But these new building types and materials also provoked experimentation – new shapes, such as the barrel vault and the arch – acquired from Rome’s expansion to the Middle East. ==

Tivoli

“Hadrian was, in architectural matters, both conservative and audacious. He was infamously respectful of Ancient Greece – comically so to some: he wore a Greek-style beard, and was nicknamed Graeculus. Many of the structures he put up, not least his own Temple of Venus and Roma, were faithful to the past. Yet the ruins of his estate at Tivoli, with its technical feats, its pumpkin domes, its space, curves and colour reveal a theme park of experimental structures that are still inspirational.” ==

Aelius Spartianus wrote: “In almost every city he built some building and gave public games. At Athens he exhibited in the stadium a hunt of a thousand wild beasts, but he never called away from Rome a single wild-beast-hunter or actor. In Rome, in addition to popular entertainments of unbounded extravagance, he gave spices to the people in honour of his mother-in-law, and in honour of Trajan he caused essences of balsam and saffron to be poured over the seats of the theatre. And in the theatre he presented plays of all kinds in the ancient manner and had the court-players appear before the public. In the Circus he had many wild beasts killed and often a whole hundred of lions. He often gave the people exhibitions of military Pyrrhic dances, and he frequently attended gladiatorial shows. He built public buildings in all places and without number, but he inscribed his own name on none of them except the temple of his father Trajan. [Source: Aelius Spartianus: Life of Hadrian,” (r. 117-138 CE.),William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“At Rome he restored the Pantheon, the Voting-enclosure, the Basilica of Neptune, very many temples, the Forum of Augustus, the Baths of Agrippa, and dedicated all of them in the names of their original builders. Also he constructed the bridge named after himself, a tomb on the bank of the Tiber, and the temple of the Bona Dea. With the aid of the architect Decrianus he raised the Colossus and, keeping it in an upright position, moved it away from the place in which the Temple of Rome is now, though its weight was so vast that he had to furnish for the work as many as twenty-four elephants. This statue he then consecrated to the Sun, after removing the features of Nero, to whom it had previously been dedicated, and he also planned, with the assistance of the architect Apollodorus, to make a similar one for the Moon.

“Most democratic in his conversations, even with the very humble, he denounced all who, in the belief that they were thereby maintaining the imperial dignity, begrudged him the pleasure of such friendliness. In the Museum at Alexandria he propounded many questions to the teachers and answered himself what he had propounded. Marius Maximus says that he was naturally cruel and performed so many kindnesses only because he feared that he might meet the fate which had befallen Domitian.

“Though he cared nothing for inscriptions on his public works, he gave the name of Hadrianopolis to many cities, as, for example, even to Carthage and a section of Athens; and he also gave his name to aqueducts without number. He was the first to appoint a pleader for the privy-purse.

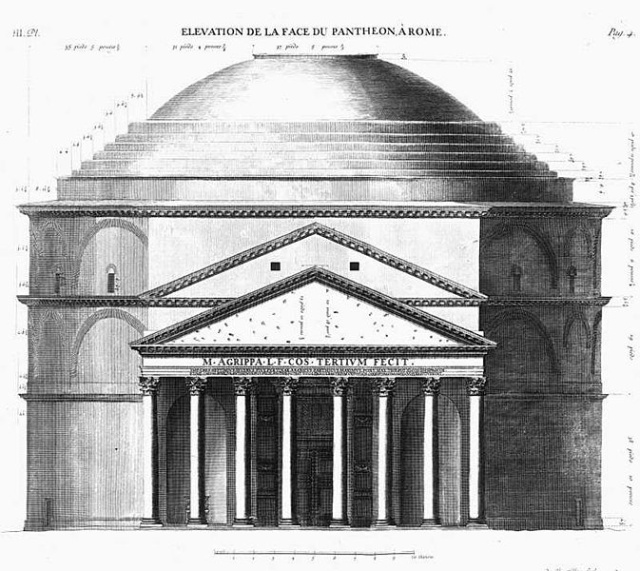

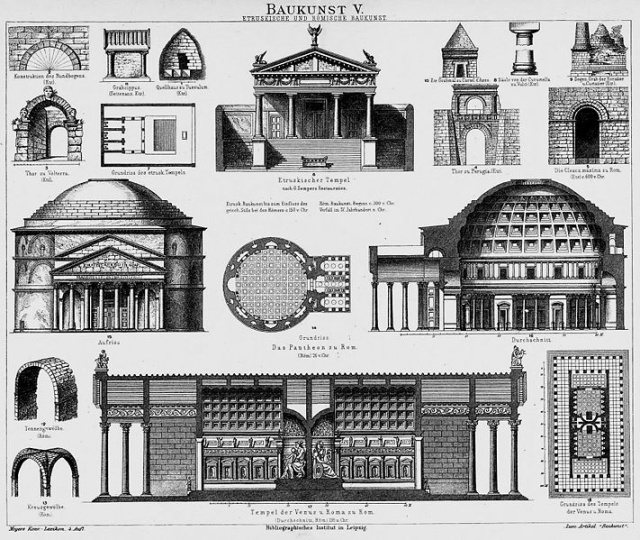

The Pantheon

The Pantheon is crowned with a massive brick and concrete dome that was the first great dome ever built and an incredible achievement at the time. It originally housed images of Roman gods and deified emperors. The huge dome is supported on eight thick pillars arranged in a circle underneath it, with the entrance occupying one of the spaces between the pillars. Between the other pillars are seven niches, each of which was originally occupied by a planetary god. The pillars are out of view behind the wall of the interior. The thickness of the dome increases from 20 feet at the base to seven feet at the top.

While the exterior looks like a linebacker the interior soars like a ballerina, as one writer put it. The only source of light is a 27 foot wide window at the top of the 142 foot-high coffered dome. The hole lets in an eye of light that moves across the interior during the day. Around the round window are coffered panels and below them are arches and pillars. Slits have been place in the marble floor to drain off the rainwater that pours in through the hole.

Nine tenths of the Pantheon is concrete. The dome was poured over "hemispherical dome of wood" with negative molds to impress the shape of the coffer. The concrete was carried up by laborers on ramps and bricks were lifted with cranes. This was all supported on "a forest of timbers, beams, and struts." The eight walls that supported the dome consisted of brick walls filled in with concrete. "Modern architects," the historian Daniel Boorstin, “are awed by the ingenuity that uses an intricate scheme of concrete reinforced arches to overarch so vast an opening and for eighteen hundred years for the dome's enormous weight."

Studies have shown that concrete was strengthened near the foundation with large heavy rocks or aggregate and lightened with pumice (light weight volcanic rock) at the top. Medieval architects could not figure out how the building was made. They believed the dome was poured over a huge mound of earth which was removed by laborers looking for pieces of gold that the "ingenious Hadrian" had scattered in the dirt. The roof of the Parthenon at one time had gilded bronze roofing tiles, but these were taken by a Byzantine emperor whose Constantinople-bound ship in turn was robbed off the coast of Sicily. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Described by Michelangelo as "an angelic not human design," the Parthenon avoided being destroyed like other Roman temples because it was consecrated as the church Sancta Maria ad Martyrs church in A.D. 609. Around the walls today are Renaissance and Baroque designs, granite columns and pediments, bronze doors, and a lot of colored marble. In the seven niches of the rotunda that once held Roman deities are altars and the tombs of Raphael and other artists and two Italian kings. Raphael painted the monuments popular cherubic angels in the 16th century.

Hadrian and The Pantheon

The Pantheon was built under Hadrian. First dedicated in 27 B.C. by Agrippa and torn down and reconstructed beginning in A.D. 119 by Hadrian, who may have designed it, the Pantheon was dedicated to all gods, most notably the seven planetary gods. It's name means "Place of all the Gods" (in Latin pan means "all" and theion means "gods"). The Pantheon was the most impressive buildings of its time. It's dome was the largest the world had ever seen. See Pantheon, Architecture.

The Pantheon today (in central Rome between Trevi Fountain and Piazza Navona) is the best preserved building from ancient Rome and one of the few buildings from the ancient world that looks pretty much the same today as it did in its time (nearly 2,000 years ago). Based on the profound effect it had on buildings that were built after it, the Parthenon is regarded by some scholars as the most important building ever built. The reason it survived and other great Roman buildings did not is that the Parthenon was converted into a church while other building were scavenged for their marble.

"The effect of the Pantheon," wrote the English poet Shelly, "is totally the reverse of that of St. Peter's. Though not a fourth part of the size, it is, as it were, the visible image of the universe; in the perfection of its proportions, as when you regard the unmeasured dome of heaven...It is open to the sky and its wide dome is lighted by an ever changing illumination of the air. The clouds of noon fly over it, and at night the keen stars are seen through the azure darkness, hanging immovably, or driving after the driven moon among the clouds." Tom Dyckoff wrote in The Times: “Hadrian began work on the Pantheon as soon as he became emperor, in A.D 117. Endowing the city with monuments to butter up the citizens had been a well-honed policy since Augustus. It was perhaps also driven by a need to escape the shadow of his predecessor and adoptive father, Trajan, who guaranteed popularity with the usual bread and circuses – wars, imperial expansion and a monument-building programme of then unprecedented scale with his architect, Apollodorus of Damascus. [Source: Tom Dyckoff, the Times, July 2008 ==]

A sinkhole that opened up near the Pantheon in 2020 in Rome’s Piazza della Rotonda exposed a section of Roman paving dating back 2,000 years. Archaeology magazine reported: Seven travertine stone slabs were revealed lying 8 feet below the modern cobblestone street surface. The slabs were part of the original Pantheon building project, carried out between 27 and 25 B.C. by the emperor Augustus’ right-hand man Marcus Agrippa. Only the facade of Agrippa’s temple remains visible today, as the structure was later rebuilt by the emperor Hadrian, who commissioned its famous dome. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-November 2020]

“But it was the Pantheon that stole the show. By now, the Roman construction industry was so sophisticated, with its mass production, standardised dimensions and prefabrication, this immense structure was put up in just ten years. It is a technical masterpiece. No dome this size had been built before – or for centuries afterwards. On deep concrete foundations, its drum rose in poured concrete layers in trenches faced with brick walls. The dome was poured on top of a vast wooden support, in sections that get lighter and thinner – though imperceptibly so to the visitor – as you ascend. Imagine the moment when the support was removed. Imagine then walking in for the first time. ==

“Much has been written on the meaning of the Pantheon, its proportional or numerical symbolism – the pleasing harmony, for instance, of the dome’s height being the same as that of the drum on which it sits. Is the oculus, open to the sky, letting light pour in, a surrogate sun? Is the dome an immense orrery (model of the solar system)? All guesswork. Though it seems safely certain that this was meant as the centrepiece of Rome’s now united and peaceful universe, a temple to all the gods. ==

“The mystery, combined with the building’s sublime simplicity, secured its reputation. Indeed the Pantheon has become the most emulated building in the world, its shape echoing in buildings from Jerusalem’s 4th-century Holy Sepulchre, through the Renaissance to the domed pavilions at Chiswick House, Stowe and Stourhead Gardens, to Smirke’s British Museum Reading Room – where the exhibition is housed. ==

“At the back of its porch, there is an inscription put there by Pope Urban VIII in 1632: “The Pantheon, the most celebrated edifice in the whole world.” Hadrian’s edifice was beyond ordinary human reputation – dedicated to gods, but also, for the first time, to architectural pleasure for its own sake. He was rare among emperors for not inscribing his structures with his own name. He didn’t need to.”

Pantheon and Concrete

The Pantheon represents the pinnacle of concrete construction. Alex Fox of the BBC wrote: Inside the Pantheon's rotunda, the distance from the floor to the very top of the dome is virtually identical to the dome's 43 meter diameter, inviting anyone inside to imagine the huge, perfect sphere that could be housed within its interior. When trying to appreciate the Pantheon's dome, "unreinforced" is really the key word. [Source: Alex Fox, BBC, December 20, 2021]

Renato Perucchio, a mechanical engineer at the University of Rochester in New York. Perucchio, said that if an architect tried to build the Pantheon today, the plans would be denied because without reinforcement, such as the steel bars commonly used in modern concrete structures, the dome would violate modern civil engineering code "The dome creates very high tensile stresses, yet it's been standing for 19 centuries," said Perucchio. "From this you can draw one of two conclusions: either gravity worked differently in Roman times; or there is knowledge that we have lost."

Apart from the unique chemistry of their concrete, the Roman architects behind the Pantheon deployed innumerable tricks to achieve their vision. Two such tricks were aimed at making the dome's walls as light as possible. During construction, the concrete that makes up the building's half-spherical ceiling had to be poured from the bottom up into wooden frames that formed successive concentric rings. But to ease the immense tensile stresses Perucchio mentioned, the builders used progressively lighter volcanic rocks as aggregate as they got closer to the dome's apex as well as making the walls themselves thinner.

At the lowest, widest part of the dome, the concrete contains large blocks of heavy basalt for strength and is about 6m thick. By contrast, the last layer surrounding the oculus uses airy pumice stone, which is so light it floats in water, as aggregate and is roughly 2m thick. The second trick can be seen all over the inside of the dome. The curved interior of the ceiling is covered in hollowed out rectangles known as coffers. These geometric coffers are mesmerising, but they're not simply there for aesthetics. They also reduced the amount of concrete required to build the dome and made it lighter, which reduced stress on the materials.

I consider it one of the most extraordinarily beautiful structures ever built "The Pantheon is a magical place," said Perucchio. "I've been there countless times, but every time I am filled with enormous admiration for the architecture and engineering involved. I consider it one of the most extraordinarily beautiful structures ever built."

Tivoli

Philosopher's Hall at Hadrian VillaTivoli (25 kilometers northeast of Rome) is the home of Hadrian's Villa, a huge sprawling villa built by the Roman Emperor Hadrian. Completed after 10 years of work, Tivoli contains 25 buildings built on 300 acres of land, including an elaborate bath house fed by water piped in from the Apennines. The buildings are now ruins. Tivoli has been a popular retreat since Roman times. It embraces the ruins of several magnificent villas including Hadrian's Villa, a lavish complex built by Emperor Hadrian, and Villa d' Este, known for its lavish gardens and plentiful cascading fountains. A pool at the banquet hall is surrounded by columns and statues of gods and caryatids.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The architecture and landscape elements described by Pliny the Younger appear as part of the Roman tradition of the monumental Hadrian's Villa. Originally built by Emperor Hadrian in the first century A.D. (120s–130s), the villa extends across an area of more than 300 acres as a villa-estate combining the functions of imperial rule (negotium) and courtly leisure (otium).” [Source: Vanessa Bezemer Sellers, Independent Scholar, Geoffrey Taylor, Department of Drawings and Prints, Metropolitan of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, known during the imperial period by the Latin name Tibur. Elena Castillo wrote in National Geographic History: The relocation of Hadrian’s permanent palace to Tibur, about 20 miles northeast of Rome, had a clear rationale behind it. Various members of the emperor’s inner circle had already built villas there. Good logistical reasons also recommended the site: The four main aqueducts that provided Rome with water passed through the town, guaranteeing the new villa’s water supply, and nearby quarries provided the main building materials. [Source: Elena Castillo, National Geographic History, January-February 2017]

“In and around its gardens, and lakes adorned with fountains and nymphs, the complex is brimming with breathtaking structures: porticoes, theaters, thermal baths, banqueting rooms, a library, and even an artificial island, all decorated with exquisite mosaics, busts, and sculptures of gods and heroes modeled on the best examples of Greek statuary.

“The entry on Hadrian in the Augustan History, a fourth-century series of imperial biographies, describes a ruler fascinated by the philosophy and architecture of the empire’s eastern provinces. The whole villa reflected the ideas and sensibilities of a highly cultured ruler. Among its many astonishing features is the elaborate portico known as the Canopus, where nighttime banquets were held. Its roof was supported by Corinthian columns, and caryatids, sculpted female figures like those of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis of Athens.

Hadrian’s Villa

Hadrian's Villa was completed in A.D. 135. The temples, gardens and theaters are full of tributes to classical Greece. Historian Daniel Boorstin it "still charm the tourist. The original country palace, stretching a full mile, displayed his experimental fantasy. There, on the shores of artificial lakes and on gently rolling hills groups of buildings celebrated Hadrian's travels in the styles of famous cities he had visited with replicas of the best he had seen. The versatile charms of the Roman baths complemented ample guest quarters, libraries, terraces, shops, museums, casinos, meeting room, and endless garden walks. There were three theaters, a stadium, an academy, and some large buildings whose function we cannot fathom. Here was a country version of Nero's Golden House."

Hadrian's Villa, also known as Villa Adriana, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. According to UNESCO: Hadrian's Villa "is an exceptional complex of classical buildings created in the 2nd century A.D. by the Roman emperor Hadrian. It combines the best elements of the architectural heritage of Egypt, Greece and Rome in the form of an 'ideal city'. Hadrian's Villa is a masterpiece that uniquely brings together the highest expressions of the material cultures of the ancient Mediterranean world. 2) Study of the monuments that make up the Hadrian's Villa played a crucial role in the rediscovery of the elements of classical architecture by the architects of the Renaissance and the Baroque period. It also profoundly influenced many 19th and 20th century architects and designers. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website]

Construction of Hadrian's Villa began in A.D. 118, a year after Hadrian became emperor, and was completed a decade later. Many parts of the estate, which once covered 600 acres, were designed by Hadrian himself, and were based on famous buildings in Egypt and in Greece. The site is organized like a city, complete with palaces, libraries, thermal baths, theaters, courtyards, and landscaped gardens watered by canals and fountains [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2013]

Awesomeness of Hadrian's Villa

Elena Castillo wrote in National Geographic History: French romantic writer Chateaubriand noted in 1803 on a visit to the emperor’s villa at Tivoli near Rome. Hadrian’s Villa’s size, opulence, and design touches from the far-flung corners of the empire are “entirely becoming for a man who once possessed the world. Although more carefully preserved since Chateaubriand wandered through its crumbling ruins, Hadrian’s Villa astounds visitors with its sheer size. Starting around A.D. 125, he oversaw the creation of 31 structures and extensive gardens, spread across a terrain of some seven square miles.

Constructing elaborate rural houses away from the heat and bustle of Rome was nothing new among members of the imperial aristocracy. Their villas were designed for the all-important Roman activity of otium — leisure — encompassing eating and reading, as well as that quality preserved in modern Italian as la dolce far niente: the sweetness of doing nothing. [Source: Elena Castillo, National Geographic History, January-February 2017]

“Hadrian’s Villa would not fill the standard role of the villa as a mere vacation home. The indefatigable Hadrian envisioned it as a place to unite business and pleasure, contemplating the beautiful hilly landscape while buckling down to the work of empire. Later emperors made use of the villa as a kind of Roman “Camp David,” but the decline of the empire left it vulnerable to looters. The complex was sacked by the Ostrogoth King Totila in A.D. 544, its massive monuments abandoned and later purloined for their stones.

“Thanks to its sheer size, however, many treasures passed unnoticed at the site for centuries. Pope Alexander VI found artworks there in the late 1400s, objects that inspired the great artists of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. It was not until 1736 that the marble sculptures known as the Furietti Centaurs were discovered. As Roman replicas of a Greek original, they symbolize the fusion of Hellenist and Latin cultures that became the guiding spirit in the building of Hadrian’s perfect palace.

Features of Hadian’s Villa

Hadrian border stone in Bulgaria

Elena Castillo wrote in National Geographic History: Most important of all, he wanted to surround himself with reminders of his astonishing travels through Spain, Egypt, the eastern provinces of the empire, and — of particular interest to this most Hellenist of emperors — Greece. He was, in the words of the scholar Tertullian, omnium curiositatum explorator, “an explorer of everything interesting,” and his villa in Tivoli reflected his restless curiosity in the vast territories under his rule. [Source: Elena Castillo, National Geographic History, January-February 2017]

“Named for the ancient city near Alexandria in Egypt, the Canopus’s 390-foot-long pool is believed to represent the Nile, a river with bittersweet associations for the emperor, as this was where his lover, Antinous, had drowned during Hadrian’s tour of Egypt in 130. The city of Canopus was home to a temple of the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis, of personal importance to Hadrian, who constructed his own Serapeum at the head of the pool.

“The Villa lacked for nothing: It even included an exercise area, known as the Pecile, where the athletic emperor could carry out the Roman equivalent of the daily workout. It was equipped with a 330-foot-long rectangular pool. The court doctors had advised the emperor that he should walk two miles every day after lunch, which he could achieve by completing six circuits of the portico surrounding the pool. After exercising, Hadrian retired to his private baths, the Heliocaminus. The oldest bath complex in the villa, it was equipped with a large sauna as well as the usual frigidarium, tepidarium, and caldarium (cold, warm, and hot rooms).

“The vast residential complex was almost always teeming with people: members of the court, guests, and, of course, an army of servants. The servants’ lodgings, and the way they moved around the complex, were ingeniously designed so that the villa’s residents barely noticed they were there. Staff lived in hidden rooms, and moved around the site through a series of service tunnels, in order to distribute food or access the ovens that heated the hypocausts for the baths.

One of the most interesting features in the Vatican's Egyptians Museum is a the recreation of an Egyptian-style room found in the palace of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. Among the many Egyptian-style Roman pieces here is a Pharaoh-like rendering of Hadrian's male lover Antinoüs.

Underground Tunnels at Hadrian’s Villa

Rossella Lorenzi wrote in Archaeology magazine: “A group of Italian caving enthusiasts, investigating a small hole in the ground concealed by bushes, discovered surprising information about the inner workings of Hadrian’s Villa. Some time ago, archaeologists realized that there was a network of roads under the estate, says Marco Placidi, director of Underground Rome, the group that made the discovery. “As we explored the roads, we discovered another world,” he says. “The villa’s grandeur is reflected underground.” [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2013]

In its day, the villa’s subterranean world would have bustled with the activity of people charged with running the sprawling imperial palace as smoothly and quietly as possible. Tunnels and passageways allowed thousands of slaves to move discreetly from the basement of one building to that of another, enabled the movement of ox carts loaded with food and goods destined for underground storage, and accommodated sewers and water pipes. “These underground passageways have long been known,” says Benedetta Adembri, the director of the site. But Placidi’s team has discovered a new tunnel double the width — an astonishing 19 feet wide — of any previously found. This roadway would have allowed for two-way traffic.

Hadrian’s Defenses

Hadrian ended the wave of conquest and expansion that occurred under his predecessor Trajan and enclosed the empire within clearly-defined frontiers. Hadrian did not believe that the mission of Rome was to conquer the world, but to civilize her own subjects. He therefore voluntarily gave up the extensive conquests of Trajan in the East, the provinces of Armenia, Mesopotamia, an Assyria. He declared that the Eastern policy of Trajan was a great mistake. He openly professed to cling to the policy of Augustus, which was to improve the empire rather than to enlarge it. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Hadiran's Wall

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “From around 500 B.C., Rome expanded continually for six centuries, transforming itself from a small Italian city-state in a rough neighborhood into the largest empire Europe would ever know. The emperor Trajan was an eager heir to this tradition of aggression. Between 101 and 117, he fought wars of conquest in present-day Romania, Armenia, Iran, and Iraq, and he brutally suppressed Jewish revolts. Roman coins commemorated his triumphs and conquests. When he died in 117, his territory stretched from the Persian Gulf to Scotland. He bequeathed the empire to his adopted son—a 41-year-old Spanish senator, self-styled poet, and amateur architect named Publius Aelius Hadrianus. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, September 2012]

“Faced with more territory than Rome could afford to control and under pressure from politicians and generals to follow in the footsteps of his adoptive father, the newly minted emperor—better known as Hadrian—blinked. “The first decision he made was to abandon the new provinces and cut his losses,” says biographer Anthony Birley. “Hadrian was wise to realize his predecessor had bitten off more than he could chew.” The new emperor’s policies ran up against an army accustomed to attacking and fighting on open ground. Worse, they cut at the core of Rome’s self-image. How could an empire destined to rule the world accept that some territory was out of reach?

“Hadrian may simply have recognized that Rome’s insatiable appetite was yielding diminishing returns. The most valuable provinces, like Gaul or Hadrian’s native Spain, were full of cities and farms. But some fights just weren’t worth it. “Possessing the best part of the earth and sea,” the Greek author Appian observed, the Romans have “aimed to preserve their empire by the exercise of prudence, rather than to extend their sway indefinitely over poverty-stricken and profitless tribes of barbarians.”

“The army’s respect for Hadrian helped. The former soldier adopted a military-style beard, even in official portraits, a first for a Roman emperor. He spent more than half of his 21-year reign in the provinces and visiting troops on three continents. Huge stretches of territory were evacuated, and the army dug in along new, reduced frontiers. Wherever Hadrian went, walls sprang up. “He was giving a message to expansion-minded members of the empire that there were going to be no more wars of conquest,” Birley says.

“By the time the restless emperor died in 138, a network of forts and roads originally intended to supply legions on the march had become a frontier stretching thousands of miles. “An encamped army, like a rampart, encloses the civilized world in a ring, from the settled areas of Aethiopia to the Phasis, and from the Euphrates in the interior to the great outermost island toward the west,” Greek orator Aelius Aristides noted proudly, not long after Hadrian’s death.”

Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's WallEmperor Hadrain (A.D. 76-138) ordered and oversaw the building of Hadrian’s Wall near the present-day border between Scotland and England to protect the unstable British provinces from fierce tribes such as the Caledonians, Picts and "Raiding Scots" in present-day Scotland. Hadrian's Wall was a Roman frontier built between A.D. 122 and 130. Running for 117 kilometers (73 miles) between Wallsend-on-Tyne in the east to Bowness on the Solway Firth in the west, it makes use of ridges and crags, particularly Whin Sill, and offers goods view to the north. A deep ditch reinforced some parts of it. Other parts were built on the top of cliffs.

Built by largely by Roman troops, Hadrians Wall is the most lasting and famous monument left behind by the Romans in Britain and remains a powerful symbol of Roman rule. Stretching from the North Sea near the east coast town of Newcastle to the Irish Sea near Carlisle in the west, the 2000-year-old wall snakes through treeless valleys and over bluffs in a land as big as the sky. The 12 best preserved miles of the wall are located in Northumberland National Park where hills gently rise and fall like waves in a calm sea.

Hadrian’s Wall was built to keep the tribes northern tribes from invading Roman Britain. It was not formidable enough to keep determined individuals out, but it was obstructive enough to halt an invading army, with its requisite supply wagons and horses. The wall also signified the limit of Roman expansion. By building it from sea to sea, the Romans admitted they did not have the resources to pacify the tribes in Scotland. The goal was to keep them at bay. In the A.D. 2nd century, the Roman Empire reached its limit and one of Hadrian’s major contributions was saying enough was enough: lets focus on keeping the existing empire together rather being compelled to constantly expand it.

During Roman times Hadrian’s Wall was 10 feet wide and 13 and 15 feet high— high enough so that a man standing on the shoulders of another man still couldn't reach the top. Signal stations were set up every mile and every five miles or so there was a castle. As a testimony of how much the Scots were feared 13,000 soldiers and 5,500 horsemen were positioned along the wall. To put these numbers in perspective William the Conqueror captured England with a force of only 7,000 men.

During Roman Times, a traditional fighting ditch stood on the north side of the wall. On the south side was a 10-foot-deep, 20-foot-wide ditch intended to keep smugglers and local inhabitants at bay. Causeways were built across these ditches at the forts. The largest fort enclosed nine acres and housed 1000 men. Each fort had a central headquarters, a chapel for storing sacred weapons, rows of slate-roofed barracks, storage granaries, cookhouses and latrines with running water large enough to accommodate 20 men at one time.

Hadrian's wall was made from 25 million lunch-box-size stones. In the interior of the wall was poured mortar, and tons of rubble, dirt and gravel. The wall was built at a rate of five wall miles and one fort a year per legion. Although the wall wasn't finished until A.D. 122 most of the work was complete in three years.

See Separate Article: ROMAN MILITARY IN BRITAIN: SOLDIERS, HADRIAN’S WALL AND VINDOLANDA europe.factsanddetails.com

RELATED ARTICLES: HADRIAN’S WALL europe.factsanddetails.com

Hadrian Tours in the Provinces

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: After consolidating his power, in 122 he set about a grand tour of his empire, starting in his Iberian homeland and working his way east. Writing in the third century, the North African theologian Tertullian described Hadrian’s urge “to be an explorer of everything.” His travels combined a shrewd military eye with a scholar’s avid interest. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, December 4, 2020]

Hadrian spent more than half (maybe as much a two thirds) of his 21-year reign on the road outside Italy, primarily overseeing the construction of new cities and fortifications along the frontier. He originally set out from Rome with the purpose of studying the many tribes and cultures in his vast empire. "He marched on foot and bareheaded over the snows of Cledonia and the sultry plains of Egypt," wrote 18th century historian Edward Gibbons. During his rule Hadrian’s Wall was erected in northwest England, Hadrian's Gate was built in southern Turkey and Hadrian's Theater was constructed in Carthage. Hadrian united Greece into a confederation with a headquarters in Athens. He codified Athenian Law, finished the Temple of Zeus in Olympia (one of the seven wonders) and rebuilt the shrines in Delphi. Hadrian also outlawed circumcision which lead to a Jewish revolt.

Hadrian coin from Africa

Hadrian showed a stronger sympathy with the provinces than any of his predecessors, and under his reign the provincials attained a high degree of prosperity and happiness. He conducted himself as a true sovereign and friend of his people. To become acquainted with their condition and to remedy their evils, he spent a large part of his time in visiting the provinces. Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: “Trajan’s reign had been one of warfare and territorial expansion, when the empire reached its greatest extent. By contrast, Hadrian’s reign was one of peace and consolidation, except for a serious revolt in Judaea in 132 AD. In Africa he built walls to control the transhumance routes, and in Germany he built a palisade with watch towers and small forts to delineate Roman-controlled territory. In Britain, he built the stone wall which bears his name, perhaps the most enduring of his frontier lines. [Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Hadrian made his temporary residence in the chief cities of the empire,—in York, in Athens, in Antioch, and in Alexandria—where he was continually looking after the interests of his subjects. In the provinces, as at Rome, he constructed many magnificent public works; and won for himself a renown equal, if not superior, to that of Trajan as a great builder. Rome was decorated with the temple of Venus and Roma, and the splendid mausoleum which to-day bears the name of the Castle of St. Angelo. Hadrian also built strong fortifications to protect the frontiers, one of these connecting the head waters of the Rhine and the Danube, and another built on the northern boundary of Britain. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The general organization of the provinces remained with few changes. There were still the two classes, the senatorial, governed by the proconsuls and propraetors, and the imperial, governed by the legati, or the emperor’s lieutenants. The improvement which took place under the empire in the condition of the provinces was due to the longer term of office given the governors, the more economic management of the finances, and the abolition of the system of farming the revenues. \~\

The good influence of such emperors as Hadrian is seen in the new spirit which inspired the life of the provincials. The people were no longer the prey of the taxgatherer, as in the times of the later republic. They could therefore use their wealth to improve and beautify their own cities. The growing public spirit is seen in the new buildings and works, everywhere erected, not only by the city governments, but by the generous contributions of private citizens. The relations between the people of different provinces were also becoming closer by the improvement of the means of communication. The roads were now extended throughout the empire, and were used not merely for the transportation of armies, but for travel and correspondence. The people thus became better acquainted with one another. Many of the highways were used as post-roads, over which letters might be sent by means of private runners or government couriers. \~\

The different provinces of the empire were also brought into closer communication by means of the increasing commerce, which furnished one of the most honored pursuits of the Roman citizen. The provinces encircled the Mediterranean Sea, which was now the greatest highway of the empire. The sea was traversed by merchant ships exchanging the products of various lands. The provinces of the empire were thus joined together in one great commercial community.” \~\

Hadrian in Gaul and Britain

Hadrian visiting a Romano-British pottery manufacturer

Aelius Spartianus wrote: “After this he travelled to the provinces of Gaul, and came to the relief of all the communities with various acts of generosity; and from there he went over into Germany. Though more desirous of peace than of war, he kept the soldiers in training just as if war were imminent, inspired them by proofs of his own powers of endurance, actually led a soldier's life among the maniples, and, after the example of Scipio Aemilianus, Metellus, and his own adoptive father Trajan, cheerfully ate out of doors such camp-fare as bacon, cheese and vinegar. And that the troops might submit more willingly to the increased harshness of his orders, he bestowed gifts on many and honours on a few. For he re-established the discipline of the camp, which since the time of Octavian had been growing slack through the laxity of his predecessors. He regulated, too, both the duties and the expenses of the soldiers, and now no one could get a leave of absence from camp by unfair means, for it was not popularity with the troops but just deserts that recommended a man for appointment as tribune. [Source: Aelius Spartianus: Life of Hadrian,” (r. 117-138 CE.),William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“He incited others by the example of his own soldierly spirit; he would walk as much as twenty miles fully armed; he cleared the camp of banqueting-rooms, porticoes, grottos, and bowers, generally wore the commonest clothing, would have no gold ornaments on his sword-belt or jewels on the clasp, would scarcely consent to have his sword furnished with an ivory hilt, visited the sick soldiers in their quarters, selected the sites for camps, conferred the centurion's wand on those only who were hardy and of good repute, appointed as tribunes only men with full beards or of an age to give to the authority of the tribuneship the full measure of prudence and maturity, permitted no tribune to accept a present from a soldier, banished luxuries on every hand, and, lastly, improved the soldiers' arms and equipment. Furthermore, with regard to length of military service he issued an order that no one should violate ancient usage by being in the service at an earlier age than his strength warranted, or at a more advanced one than common humanity permitted. He made it a point to be acquainted with the soldiers and to know their numbers.Besides this, he strove to have an accurate knowledge of the military stores, and the receipts from the provinces he examined with care in order to make good any deficit that might occur in any particular instance. But more than any other emperor he made it a point not to purchase or maintain anything that was not serviceable.

“And so, having reformed the army quite in the manner of a monarch, he set out for Britain, and there he corrected many abuses and was the first to construct a wall, eighty miles in length, which was to separate the barbarians from the Romans. He removed from office Septicius Clarus, the prefect of the guard, and Suetonius Tranquillus, the imperial secretary, and many others besides, because without his consent they had been conducting themselves toward his wife, Sabina, in a more informal fashion than the etiquette of the court demanded. And, as he was himself wont to say, he would have sent away his wife too, on the ground of ill-temper and irritability, had he been merely a private citizen. Moreover, his vigilance was not confined to his own household but extended to those of his friends, and by means of his private agents he even pried into all their secrets, and so skilfully that they were never aware that the Emperor was acquainted with their private lives until he revealed it himself. In this connection, the insertion of an incident will not be unwelcome, showing that he found out much about his friends. The wife of a certain man wrote to her husband, complaining that he was so preoccupied by pleasures and baths that he would not return home to her, and Hadrian found this out through his private agents. And so, when the husband asked for a furlough, Hadrian reproached him with his fondness for his baths and his pleasures. Whereupon the man exclaimed: "What, did my wife write you just what she wrote to me?" And, indeed, as for this habit of Hadrian's, men regard it as a most grievous fault, and add to their criticism the statements which are current regarding the passion for males and the adulteries with married women to which he is said to have been addicted, adding also the charges that he did not even keep faith with his friends.”

Hadrian in Spain and Egypt

Hadrian coin from Egypt

Aelius Spartianus wrote: “After arranging matters in Britain he crossed over to Gaul, for he was rendered anxious by the news of a riot in Alexandria, which arose on account of Apis; for Apis had been discovered again after an interval of many years, and was causing great dissension among the communities, each one earnestly asserting its claim as the place best fitted to be the seat of his worship. During this same time he reared a basilica of marvellous workmanship at Nimes in honour of Plotina. After this he travelled to Spain and spent the winter at Tarragona, and here he restored at his own expense the temple of Augustus. To this place, too, he called all the inhabitants of Spain for a general meeting, and when they refused to submit to a levy, the Italian settlers jestingly, to use the very words of Marius Maximus, and the others very vigorously, he took measures characterized by skill and discretion. At this same time he incurred grave danger and won great glory; for while he was walking about in a garden at Tarragona one of the slaves of the household rushed at him madly with a sword. But he merely laid hold on the man, and when the servants ran to the rescue handed him over to them. Afterwards, when it was found that the man was mad, he turned him over to the physicians for treatment, and all this time showed not the slightest sign of alarm. [Source: Aelius Spartianus: Life of Hadrian,” (r. 117-138 CE.),William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“During this period and on many other occasions also, in many regions where the barbarians are held back not by rivers but by artificial barriers, Hadrian shut them off by means of high stakes planted deep in the ground and fastened together in the manner of a palisade. He appointed a king for the Germans, suppressed revolts among the Moors, and won from the senate the usual ceremonies of thanksgiving. The war with the Parthians had not at that time advanced beyond the preparatory stage, and Hadrian checked it by a personal conference.

“During a journey on the Nile he lost Antinous, his favourite, and for this youth he wept like a woman. Concerning this incident there are varying rumours; for some claim that he had devoted himself to death for Hadrian, and others -- what both his beauty and Hadrian's sensuality suggest. But however this may be, the Greeks deified him at Hadrian's request, and declared that oracles were given through his agency, but these, it is commonly asserted, were composed by Hadrian himself.”

Hadrian in Greece and Asia Minor

Hadrian Temple in Ephesus, present-day Turkey

Aelius Spartianus wrote: “After this Hadrian travelled by way of Asia and the islands to Greece, and, following the example of Hercules and Philip, had himself initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries. He bestowed many favours on the Athenians and sat as president of the public games. And during this stay in Greece care was taken, they say, that when Hadrian was present, none should come to a sacrifice armed, whereas, as a rule, many carried knives. Afterwards he sailed to Sicily, and there he climbed Mount Aetna to see the sunrise, which is many-hued, they say, like a rainbow. Thence he returned to Rome, and from there he crossed over to Africa, where he showed many acts of kindness to the provinces. Hardly any emperor ever travelled with such speed over so much territory. [Source: Aelius Spartianus: Life of Hadrian,” (r. 117-138 CE.),William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“Finally, after his return to Rome from Africa, he immediately set out for the East, journeying by way of Athens. Here he dedicated the public works which he had begun in the city of the Athenians, such as the temple to Olympian Jupiter and an altar to himself; and in the same way, while travelling through Asia, he consecrated the temples called by his name. Next, he received slaves from the Cappadocians for service in the camps. To petty rulers and kings he made offers of friendship, and even to Osdroes, king of the Parthians. To him he also restored his daughter, who had been captured by Trajan, and promised to return the throne captured at the same time. And when some of the kings came to him, he treated them in such a way that those who had refused to come regretted it. He took this course especially on account of Pharasmanes, who had haughtily scorned his invitation. Furthermore, as he went about the provinces he punished procurators and governors as their actions demanded, and indeed with such severity that it was believed that he incited those who brought the accusations.

“In the course of these travels he conceived such a hatred for the people of Antioch that he wished to separate Syria from Phoenicia, in order that Antioch might not be called the chief city of so many communities. At this time also the Jews began war, because they were forbidden to practise circumcision. As he was sacrificing on Mount Casius, which he had ascended by night in order to see the sunrise, a storm arose, and a flash of lightning descended and struck both the victim and the attendant. He then travelled through Arabia and finally came to Pelusium, where he rebuilt Pompey's tomb on a more magnificent scale.

Hadrian's Love of the Greeks

Hadrian loved ancient Greece and ancient Greek culture. And, what he absorbed he gave back. He transformed Athens into a new cultural center and was worshipped there as a god, which was made clear when he visited Athens.Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Any city awaiting a visit from a Roman emperor would have thrummed with anticipation, but for Athenians in A.D. 124, the expectation was even greater. Hadrian, whose realm stretched from Britain to Babylonia, had a well-known passion for Greece, which he had cultivated since he was a child. Out of all the cities under Rome’s control, Hadrian selected Athens as his intellectual home, a city on which he would lavish funds on building monuments. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, December 4, 2020]

Hadrian’s relationship with the city of Plato and Pericles was reciprocated by the Athenians, who came to regard the emperor as their city’s new founder and a deity in his own right. The monuments he built in Athens reflected not just its ancient glory but its modern importance too: Hadrian knew that his exaltation and improvement of the city would help stabilize the fractious eastern part of the sprawling Roman Empire he had come to rule.

Athenians showered honors and plaudits on their returning son. In March 125 he presided over the Greater Dionysia, the city’s ancient dramatic festival. But the emperor was not content with merely a passive role and set himself a monumental challenge: to finish the city’s Olympieion, a temple dedicated to Olympian Zeus. A temple had stood on the site since the sixth century B.C. In the second century B.C., the Seleucid kings, successors of Alexander the Great, attempted to rebuild it, without success. Emperor Augustus had toyed with restoring it to glory, but never did—and so Hadrian set out to succeed where others had failed. (The Greeks changed the idea of the afterlife.)

Hadrian wanted the Olympieion to exceed the Parthenon in splendor. It was to have more than a hundred Corinthian columns, the most ornate variety. They would be adorned with acanthus leaves, a symbol of the regeneration of Greece brought about by himself as the “Roman Pericles.” In his bold architectural vision, he pictured the Olympieion as the nerve center of a new district stretching along the Ilissos River. Immediately, local elites became caught up in the emperor’s enthusiasm and joined forces to support the project, amid a jubilant expectation that glorious years lay ahead for Greece.

For the emperor’s third visit in 128, Hadrian was accompanied on his grand tour by his lover, Antinous, then in his late teens, and renowned for his beauty. The two were invited to attend the Eleusinian Mysteries, a secret rite practiced by the city’s elite, which centered on the myth of Demeter and Persephone. After taking their fill of Athenian hospitality, Hadrian continued toward Egypt. In 130 Antinous drowned under mysterious circumstances while being conveyed by boat along the Nile. A year later, still grieving, Hadrian began his last imperial visit to Athens for the consecration of the Olympieion.

It had been a busy few years for the city. Awash with imperial money, the Athenians were embarking on huge building projects, including the just completed Arch of Hadrian to welcome their returning patron. The inauguration ceremony in the newly completed Olympieion was held in the presence of envoys from all over the Roman world. According to second-century historian Pausanias, the temple housed a colossal ivory and gold statue of Zeus, exceeding in size “all others except the Colossi of Rhodes and Rome.” The temple’s dedication to Zeus was nominal: It was essentially a center for the cult of Hadrian himself.

During this visit, the emperor was no less prolific in his efforts to build up Athens. He established the Panhellenion, a Greek federation drawn from seven Roman provinces, which would hold annual assemblies and games. Historians consider the league as essentially cultural and symbolic. The sense of Panhellenic (“All the Greeks”) is questionable, as Hadrian’s own notions of what constituted Greekness were highly romanticized. He also ordered of the construction of a new library, the largest Athens had ever seen. On completion it included upper galleries for storage and an arcaded courtyard with gardens and a pond.

Hadrian: Propaganda. Commonwealth and Consolidation

Dr Neil Faulkner wrote for the BBC: “At first, the principal audience for Roman imperial propaganda had been only a minority of the empire's population - mainly soldiers, the inhabitants of Rome and Italy, and Roman citizens living in colonies and provincial towns. |At this time, the empire was still expanding, and the role of the emperor as generalissimo was emphasised. But from the time of the emperor Hadrian (117 - 138 AD), aggressive wars all but ceased, and the empire was consolidated on existing frontiers. “As well as stressing the role of the emperor as civil ruler, Roman propagandists henceforward developed a more rounded and inclusive view of what it meant to be part of the empire. [Source: Dr Neil Faulkner, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Greek culture was embraced more wholeheartedly than before, and the resultant blending of themes and motifs produced a distinctive Graeco-Roman or 'classical' culture during the second and third centuries AD. Hadrian and his successors actively promoted the idea that the empire, while embracing a diversity of peoples and religions, was united by an overarching set of values and tastes - and therefore by loyalty to the imperial state which safeguarded these. This conception of empire as a commonwealth of the civilised - in contradistinction to both barbarians beyond and subversives within - was monumentalised in stone on the frontiers and in the cities. |::|

“Hadrian's Wall was not a defensive structure. The Roman army at the time did not fight behind fixed defences. 'He set out for Britain', Hadrian's biographer tells us, 'and there he put right many abuses and was the first to build a wall 80 miles long to separate the barbarians and the Romans.' Equally, if it was intended as a line of customs and police posts - a controlled border - it was an extraordinarily elaborate and expensive one. So what was is for? |::|

“There seems little doubt that the wall, like other great Roman frontier monuments was as much a propaganda statement as a functional facility. It was a symbolic statement of Roman grandeur and technique at the empire's furthest limit, and a marking out of the point in the landscape where civilisation stopped and the barbarian wilderness began. |::|

Roman provinces in the AD 2nd century

“Hadrian's travels took him across the empire. Everywhere - in Rome, France, Spain, Africa, Greece, Turkey, Egypt - he raised great monuments. Instead of battles, he gave the empire bath-houses. Instead of trophies, temples and theatres. Most of the ruins we see today visiting the great classical cities of the Mediterranean are of public buildings erected in the second century golden age of imperial civilisation inaugurated by Hadrian. Each one made a set of statements. In its functionality, it helped define the Roman lifestyle and what it meant to be 'civilised'. In its towering size and richness, it spoke of the wealth and success of empire. |Through images on fresco, mosaic and sculpted panel, it promoted a cultural identity and shared values. And in the very fact of its existence, it redounded to the credit of the regime whose guiding hand had made it possible.” |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024