PARTS OF A ROMAN HOUSE

Parts of a domus (an ancient Roman house)

The roof of a typical house was covered by pottery tiles and designed so it directed water into a storage basin. During Roman times, when urban areas became crowded and concrete construction was developed, houses with several stories were built for the first time on a large scale. Rural houses were surrounded by sheep pens, small orchards and gardens that varied in size depending on how rich the owner was. Many families kept bees in pottery hives. ||

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Roman “houses were in some ways similar to those of today. They had two stories, although the second story rarely survives. They contained bedrooms, a dining room, a kitchen, but there were also spaces specific to Roman houses: the atrium was a typical early feature of houses in the western half of the empire, a shaded walkway surrounding a central impluvium or pool, which served as the location for the owner's meeting with his clients in the morning; the tablinum was a main reception room emerging from the atrium, where the owner often sat to receive his clients; and finally, the peristyle was an open-air courtyard of varying size, laid out as a garden normally in the West, but paved with marble in the East.” [Source: Ian Lockey, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org]

The uncovered ruins of Pompeii show to us a great many houses, from the most simple to the elaborate “House of Pansa.” The ordinary house (domus) consisted of front and rear parts connected by a central area, or court. The front part contained the entrance hall (vestibulum); the large reception room (atrium); and the private room of the master (tablinum), which contained the archives of the family. The large central court was surrounded by columns (peristylum). The rear part contained the more private apartments—the dining room (triclinium), where the members of the family took their meals reclining on couches; the kitchen (culina); and the bathroom (balneum).” [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSES factsanddetails.com ;

FEATURES OF ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSES: WALLS, DOORS, ROOFS, HEATING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FURNITURE IN ANCIENT ROME: BEDS, COUCHES, TABLES, CHAIRS, FRIDGES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN POSSESSIONS, TOOLS, KITCHEN STUFF, AND PERSONAL OBJECTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ARCHITECTURE: EMPERORS, ARCHES AND CONCRETE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.- A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration” by by John R. Clarke Amazon.com;

“Houses, Villas, and Palaces in the Roman World” by Alexander Gordon McKay (1975) Amazon.com;

“Style and Function in Roman Decoration: Living with Objects and Interiors”

by Ellen Swift (2018) Amazon.com;

“Domus: Wall Painting in the Roman House” by Donatella Mazzoleni , Umberto Pappalardo, et al. (2005) Amazon.com;

“Water Displays in Domestic Spaces across the Late Roman West: Cultivating Living Buildings” by Ginny Wheeler (2025) Amazon.com;

“Roman Gardens” by Anthony Beeson (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Jane F. Gardner, Thomas Wiedemann Amazon.com;

“The Roman House and Social Identity” by Shelley Hales Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (1996) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in the Later Roman” by Kim Bowes, Richard Hodges Amazon.com;

“At Home in Roman Egypt: A Social Archaeology” by Anna Lucille Boozer (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Spread of the Roman Domus-Type in Gaul” by Lorinc Timar (2011) Amazon.com;

“Multisensory Living in Ancient Rome: Power and Space in Roman Houses”

by Hannah Platts Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins (1986) Amazon.com;

“Life in Ancient Rome: People & Places”, 450 Pictures, Maps And Artworks,

by Nigel Rodgers (2014) Amazon.com;

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Vestibulum and Ostium

The city house was built on the street line. In the poorer houses the door opening into the atrium was in the front wall, and was separated from the street only by the width of the threshold. In the better sort of houses those described in the last section, the separation of the atrium from the street by the row of shops gave opportunity for arranging a more imposing entrance. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Pompeii street

“Sometimes a part, at least, of this space was left as an open court, with a costly pavement running from the street to the door, the court was adorned with shrubs, flowers, statuary even, and trophies of war, if the owner was rich and a successful general. This courtyard was called the vestibulum. The important point to notice is that it does not correspond at all to the part of a modern house called, after it, the vestibule. In this vestibulum the clients gathered, before daybreak perhaps, to wait for admission to the atrium, and here the sportula was doled out to them. Here, too, was arranged the wedding procession, and here was marshaled the train that escorted the boy to the Forum the day that he put away childish things. Even in the poorer houses the same name was given to the little space between the door and the inner edge of the sidewalk. |+|

“The Ostium. The entrance to the house was called the ostium. This includes the doorway and the door itself, and the word is applied to either, though fores and ianua are the more precise words for the door. In the poorer houses the ostium was directly on the street, and there can be no doubt that it originally opened directly into the atrium; in other words, the ancient atrium was separated from the street only by its own wall. The refinement of later times led to the introduction of a hall or passageway between the vestibulum and the atrium, and the ostium opened into this hall and gradually gave its name to it. The door was placed well back, leaving a broad threshold (limen), which often had the word Salve worked on it in mosaic. Sometimes over the door were words of good omen, Nihil intret mali, for example, or a charm against fire. In the houses where an ostiarius or ianitor was kept on duty, his place was behind the door; sometimes he had here a small room. A dog was often kept chained inside the ostium, or in default of one a picture of a dog was painted on the wall or worked in mosaic on the floor with the warning beneath it: Cave canem! The hallway was closed on the side of the atrium with a curtain (velum). Through this hallway persons in the atrium could see passers-by in the street.” |+|

Atrium of a Roman House

The atrium was the kernel of the Roman house. The most conspicuous features of the atrium were the compluvium and the impluvium. The water collected in the latter was carried into cisterns; across the former a curtain could be drawn when the light was too intense, as across a photographer’s skylight nowadays. We find that the two words were carelessly used for each other by Roman writers. So important was the compluvium to the atrium that the atrium was named from the manner in which the compluvium was constructed. Vitruvius tells us that there were four styles. The first was called the atrium Tuscanicum. In this the roof was formed by two pairs of beams crossing each other at right angles; the inclosed space was left uncovered and thus formed the compluvium. It is evident that this mode of construction could not be used for rooms of large dimensions. The second was called atrium tetrastylon. The beams were supported at their intersections by pillars or columns. The third, atrium Corinthium, differed from the second only in having more than four supporting pillars. The fourth was called the atrium displuviatumIn this the roof sloped toward the outer walls, and the water was carried off by gutters on the outside; the impluvium collected only so much water as actually fell into it from the heavens. We are told that there was another style of atrium, the testudinatum, which was covered all over and had neither impluvium nor compluvium. We do not know how this was lighted. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

atrium interior

The Change in the Atrium. The simplicity and purity of the family life of that period lent a dignity to the one-room house that the vast palaces of the late Republic and Empire failed utterly to inherit. By Cicero’s time the atrium had ceased to be the center of domestic life; it had become a state apartment used only for display. We do not know the successive steps in the process of change. Probably the rooms along the sides of the atrium were first used as bedrooms, for the sake of greater privacy. The necessity of a detached room for the cooking, and then of a dining-room, must have been felt as soon as the peristylium was adopted (it may well be that this court was originally a kitchen garden). Then other rooms were added about the peristylium, and these were made sleeping apartments for the sake of still greater privacy. From the Marble Plan, now in the Antiquarium at RomeFinally these rooms were needed for other purposes and the sleeping rooms were moved again, this time to an upper story. When this second story was added we do not know, but it presupposes the small and costly lots of a city. Even unpretentious houses in Pompeii have in them the remains of staircases. |+| “The atrium was now fitted up with all the splendor and magnificence that the owner’s means would permit. The opening in the roof was enlarged to admit more light, and the supporting pillars were made of marble or costly woods. Between these pillars, and along the walls, statues and other works of art were placed. The impluvium became a marble basin, with a fountain in the center, and was often richly carved or adorned with figures in relief. The floors were mosaic, the walls painted in brilliant colors or paneled with marbles of many hues, and the ceilings were covered with ivory and gold. In such an atrium the host greeted his guests, the patron, in the days of the Empire, received his clients, the husband welcomed his wife, and here the master’s body lay in state when the pride of life was over. |+|

“Still, some memorials of the older day were left in even the most imposing atrium. The altar to the Lares and Penates sometimes remained near the place where the hearth had been, though the regular sacrifices were made in a special chapel in the peristylium. In even the grandest houses the implements for spinning were kept in the place where the matron had once sat among her slave women, as Livy tells us in the story of Lucretia. The cabinets retained the masks of simpler and, perhaps, stronger men, and the marriage couch stood opposite the ostium (hence its other name, lectus adversus), where it had been placed on the wedding night, though no one slept in the atrium. In the country much of the old-time use of the atrium survived even in the days of Augustus, and the poor, of course, had never changed their style of living. What use was made of the small rooms along the sides of the atrium, after they had ceased to be bedchambers, we do not know; they served, perhaps, as conversation rooms, private parlors, and drawing-rooms.” |+|

Alae, Tablinum and Peristylium

The manner in which the alae, or wings, were formed has been explained; they were simply the rectangular recesses left on the right and left of the atrium when the smaller rooms on those sides were walled off. It must be remembered that they were entirely open to the atrium and formed a part of it. In them were kept the imagines (the wax busts of those ancestors who had held curule offices), arranged in cabinets in such a way that, by the help of cords running from one to another and of inscriptions under each of them, the relations of the men to one another could be made clear and their great deeds kept in mind. Even when Roman writers or those of modern times speak of the imagines as in the atrium, it is the alae that are intended. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Peristylium

“The Tablinum. The possible origin of the tablinum has already been explained. Its name has been derived from the material (tabulae, “planks”) of the “lean-to,” from which, perhaps, it developed. Others think that the room received its name from the fact that in it the master kept his account books (tabulae) as well as all his business and private papers. This is unlikely, for the name was probably fixed before the time when the room was used for this purpose. He kept here also the money chest or strong box (arca), which in the olden time had been chained to the floor of the atrium, and made the room in fact his office or study. By its position it commanded the whole house, as the rooms could be entered only from the atrium or peristylium, and the tablinum was right between them. The master could secure entire privacy by closing the folding doors which cut off the peristylium, the private court, or by pulling the curtains across the opening into the atrium, the great hall. On the other hand, if the tablinum was left open, the guest entering the ostium must have had a charming vista, commanding at a glance all the public and semi-public parts of the house. Even when the tablinum was closed, there was free passage from the front of the house to the rear through the short corridor by the side of the tablinum. |+|

“The Peristylium. The peristylium, or peristylum, was adopted, as we have seen, from the Greeks, but despite the way in which the Roman clung to the customs of his fathers it was not long in becoming the more important of the two main sections of the house. We must think of a spacious court open to the sky, but surrounded by rooms, all facing it and having doors and latticed windows opening upon it. All these rooms had covered porches on the side next the court. These porches, forming an unbroken colonnade on the four sides, were strictly the peristyle, though the name came to be used of this whole section of the house, including court, colonnade, and surrounding rooms. The court was much more open to the sun than the atrium was; all sorts of rare and beautiful plants and flowers flourished in this spacious court, protected by the walls from cold winds. The peristylium was often laid out as a small formal garden, having neat geometrical beds edged with bricks. Careful excavation at Pompeii has even given an idea of the planting of the shrubs and flowers. Fountains and statuary adorned these little gardens; the colonnade furnished cool or sunny promenades, no matter what the time of day or the season of the year. Since the Romans loved the open air and the charms of nature, it is no wonder that they soon made the peristyle the center of their domestic life in all the houses of the better class, and reserved the atrium for the more formal functions which their political and public position demanded. It must be remembered that there was often a garden behind the peristyle, and there was also very commonly a direct connection between the peristyle and the street.” |+|

Rooms in a Roman Home

The rooms surrounding the peristylium varied so much with the means and tastes of the owners of the houses that we can hardly do more than give a list of those most frequently mentioned in literature. It is important to remember that in the town house all these rooms received their light by day from the peristylium. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

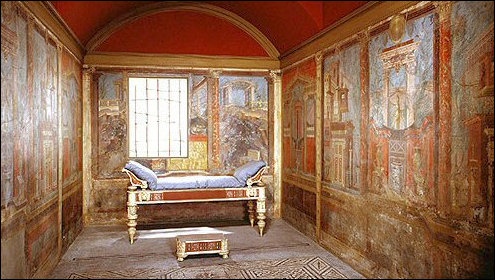

Cubiculum of a villa at Boscoreale

“A library (bibliotheca) had its place in the house of every Roman of education. Collections of books were large as well as numerous, and were made then, as now, even by persons who cared nothing about their contents. The books, or rolls, which will be described later, were kept in cases or cabinets around the walls. In one library discovered in Herculaneum an additional rectangular case occupied the middle of the room. It was customary to decorate the room with statues of Minerva and the Muses, and also with the busts and portraits of distinguished men of letters. Vitruvius recommends an eastern aspect for the bibliotheca, probably to guard against dampness. |+|

“Besides these rooms, which must have been found in all good houses, there were others of less importance, some of which were so rare that we scarcely know their uses. The sacrarium was a private chapel in which the images of the gods were kept, acts of worship performed, and sacrifices offered. The oeci were halls or saloons, corresponding perhaps to our parlors and drawing-rooms, and probably used occasionally as banquet halls. The exedrae were rooms supplied with permanent seats; they seem to have been used for lectures and various entertainments. The solarium was a place in which to bask in the sun, sometimes a terrace, often the flat part of the roof, which was then covered with earth and laid out like a garden and made beautiful with flowers and shrubs. Besides these there were, of course, sculleries, pantries, and storerooms. The slaves had to have their quarters (cellae servorum), in which they were packed as closely as possible. Cellars under the houses seem to have been rare, though some have been found at Pompeii.” |+|

Bedrooms in a Roman House

The sleeping rooms (cubicula) in a Roman house were not considered so important by the Romans as by us, for the reason, probably, that they were used merely to sleep in and not for living-rooms as well. They were very small, and their furniture was scant, even in the best houses. Some of these seem to have had anterooms in connection with the cubicula, which were probably occupied by attendants. Even in the ordinary houses there was often a recess for the bed. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Some of the bedrooms seem to have been used merely for the midday siesta; these were naturally situated in the coolest part of the peristylium; they were called cubicula diurna. The others were called by way of distinction cubicula nocturna or dormitoria, and were placed so far as possible on the west side of the court in order that they might receive the morning sun. It should be remembered that, finally, in the best houses bedrooms were preferably in the second story of the peristyle. |+|

The dimensions of a Roman bedchamber habitually kept down to a minimum ; its solid shutters when shut plunged the room into complete darkness, and when open flooded it with sun or rain or draughts. It was rarely adorned with works of art Tiberius almost created a scandal by decorating his. Normally it possessed no furniture but the couch (cubile) which gave it its name; possibly a chest (area) in which materials and denarii could be stored; the chair on which Pliny the Younger would invite his friends and his secretaries to sit when they came to visit him and on which Martial would throw his cloak; and finally the chamber pot (lasanum) or the urinal (scaphium) the different models are minutely described in literature, ranging from vessels of common earthenware (matella fictilis) to others of silver set with precious stones.[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Kitchen and Dining Room in a Roman House

Kitchens generally were poorly ventilated and had packed dirt floors. They were meant for slaves only and not for public viewing. Even middle and upper class homes in Pompeii often had a tiny kitchen that was combined with the latrine. Beard wrote that the kitchen in the House of the Tragic Poet, the setting of a banquet in the popular novel The Last Days of Pompeii , would have been far too small to produce a large banquet. And worse: “Just over the back wall of the garden...was a cloth-processing workshop, or fullery. Fulling is messy business, its main ingredient being human urine...The work was noisy and smelly. In the background of Glaucus’ elegant dinner party there must have been distinctly nasty odors."

A stone cooking range and bronze cooking vessels were found in the kitchen of the House of the Vettii. Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: Cooking took place on top of the range - the bronze pots were placed on iron braziers over a small fire. In other houses, the pointed bases of amphorae storage jars were used instead of tripods to support vessels. Firewood was stored in the alcove beneath the range. Typical cooking vessels include cauldrons, skillets and pans, and reflect the fact that food generally was boiled rather than baked. Not all houses in Pompeii have masonry ranges or even separate kitchens - indeed, distinct kitchen areas generally are found only in the larger houses of the town. It is likely that in many houses cooking took place on portable braziers.” [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, March 29, 2011]

In an upper class domus the kitchen (culina) was placed on the side of the peristylium opposite the tablinum. It was supplied with an open fireplace for roasting and boiling, and with a stove not unlike the charcoal stoves still used in Europe. This was regularly of masonry, built against the wall, with a place for fuel beneath it, but there were occasional portable stoves. Kitchen utensils have been found at Pompeii. The spoons, pots and pans, kettles and pails, are graceful in form and often of beautiful workmanship. There are interesting pastry molds. Trivets held the pots and pans above the glowing charcoal on the top of the stove. Some pots stood on legs. The shrine of the household gods sometimes followed the hearth into the kitchen from its old place in the atrium. Near the kitchen was the bakery, if the mansion required one, supplied with an oven. Near it, too, was the bathhouse with the necessary closet (latrina), in order that kitchen and bathhouse might use the same sewer connection. If the house had a stable, it was also put near the kitchen, as nowadays in Latin countries. |+|

“The dining-room (triclinium) may be mentioned next. It was not necessarily closely connected with the kitchen, because, as in the Old South, lthe numbers of slaves made its position of little importance so far as convenience was concerned. It was customary to have several triclinia for use at different seasons of the year, in order that one room might be warmed by the sun in winter, and another might in summer escape its rays. Vitruvius thought the length of the triclinium should be twice its breadth, but the ruins show no fixed proportions. The Romans were so fond of air and sky that the peristylium, or part of it, must often have served as a dining-room. An outdoor dining-room is found in the so-called House of Sallust at Pompeii. Horace has a charming picture of a master, attended by a single slave, dining under an arbor.” |+|

Gardens in Ancient Rome

Most Roman houses, large or small, had a garden. Large homes had one in the courtyard and this was often where the family gathered, socialized and ate their meals. The sunny Mediterranean climate in Italy was usually accommodating to this routine. On the walls of the houses around the garden were paintings of more plants and flowers as well as exotic birds, cows, birdfeeders, and columns, as if the homeowner was trying achieve the same affects as the backdrop on a Hollywood set. Poor families tended small plots in the back of the house, or at least had some potted plants.

Getty Villa garden A peristyle garden was surrounded by a colonnade. A pool or fountain often sat at the center and space was filled with a variety of sculptures and plants. These gardens were designed be oases of green in an otherwise urban landscape. Those that could afford it decorated their gardens with busts of gods or philosophers and animal statuary. Relief ornaments called oscilas were suspended from space between columns so, as their name suggests, they could oscillate in the breeze. Some large gardens were built by wealthy Romans to display their wealth.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Beginning in the second century B.C., Rome’s most prominent families began to build luxurious country estates for which exquisitely designed gardens were essential. The Bay of Naples, with its sweeping vistas and cool breezes, became one of the most popular destinations. Today, the coastline is littered with the ruins of large villas and their opulent gardens, buried and preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79. According to Cornell University’s Kathryn Gleason, it is only recently that archaeologists have truly begun to understand the complexity and various functions of a villa garden. “A design might have been initiated as a display of wealth, but also might provide simple pleasures, such as shade, produce, a place for children to play, for weary politicians to find retreat, or for young people to make love,” she says. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, April/May 2018]

Two of the best-preserved gardens are found at the Villa of Poppaea and the Villa Arianna, located at Oplontis and Stabiae, respectively. These grand spaces contained porticoes, footpaths, fountains, and a variety of trees. In recent decades, excavations in both places have also revealed the remains of planting beds, tree root cavities, carbonized plant parts, and even in situ planting pots. “These features allow us to understand the design and layout, and thus much about the experience of the garden,” says Gleason, “which is something that only archaeology permits in a fully spatial sense.”

What was Grown in Pompeii Gardens

In Pompeii, archaeologists have reproduced Roman gardens with the same plants found in classical times. Opium was sometimes grown in Roman gardens. The Romans were obsessed with roses. Rose water bathes were available in public baths and roses were tossed in the air during ceremonies and funerals. Theater-goers sat under awning scented with rose perfume; people ate rose pudding, concocted love potions with rose oil, and stuffed their pillows with rose petals. Rose petals were a common feature of orgies and a holiday, Rosalia, was name in honor of the flower.

Pompeii created an intricate and robust system for the local production of food and wine. Researchers have long been aware of frescoes, found in many surviving houses and villas, depicting plants and the pleasure of eating and drinking. Remains of triclinia, or dining rooms, and of food stalls, bakeries, and shops selling the fish sauce garum are abundant. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, April/May 2018]

Garden archaeology as a discipline was pioneered in Pompeii in the 1950s when archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski began to excavate areas between the remaining structures. She discovered that homeowners planted flowers, dietary staples, and even small vineyards. “From the oldest type of domestic vegetable garden, the hortus, to ornate temple gardens,” explains Betty Jo Mayeske, director of the Pompeii Food and Wine Project, “you see evidence of cultivation in nearly every available space in Pompeii.” It appears that both grain and grapes were grown in small, local contexts.

Emperor’s Orchids

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The first fragments of the remarkable ancient Roman monument called the Ara Pacis (“Altar of Peace”) were found in the early sixteenth century. For the next four hundred years, the large marble altar, built to commemorate the emperor Augustus’ victories in Gaul and expansion into Spain in the first century B.C., was reassembled as pieces resurfaced until it was nearly completed in 1938. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, December 19, 2012]

“Since then, scholars have examined the altar’s heavily decorated exterior, attempting to identify the mythological and historical figures represented. However, until several years ago when archaeologist Giulia Caneva of the University of Rome was asked whether the plants and flowers represented on the Ara Pacis were faithful representations or purely fantastical—and if she could identify them—no one had carefully studied the monument’s vegetation in such detail.

“Soon Caneva discovered that the flowers were both fantasies and what she calls “extremely realistic” representations. The most surprising faithfully depicted species were two types of orchids, both of which are native to the Mediterranean. Until Caneva’s research, orchids were unknown in ancient art and had only been identified on works dating from the Renaissance and later. Caneva is continuing to decode the altar’s highly symbolic language of flowers and vegetation, which is part of the political message of this enduring monument to Augustus’ lineage and power.

Rare and Expensive Blue Room and Kitchen Shrine Found at Pompeii

In 2024, archaeologist announced the discovery of a sacred room at Pompeii with painted blue walls, a rare and expensive color in ancient Rome. It is “very unusual thing for Pompeii,” the site’s director Gabriel Zuchtriegel told NBC News. Blue “was the most expensive color” because it was difficult to make. “You had to import it from Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean and beyond. So it was expensive, and if you wanted to have something in blue, you had to pay more,” he said. Red, yellow and black were much easier to produce because natural materials like stone and sand were widely available, he added. [Source: Kelly Cobiella and Laura Saravia, NBC News, June 12, 2024]

NBC News reported: It comes from block No. 10 of Pompeii’s ninth section, a never-before excavated area of the town destroyed in the eruption of the Vesuvius volcano in 79 A.D. Decorated with female figures representing the four seasons and portrayals of agriculture and sheep farming, the room has been “interpreted as a sacrarium, a shrine devoted to ritual activities and the storage of sacred objects,” the Archaeological Park of Pompeii said in a news release. For wealthy politicians and business owners, an elaborate classical painting was a prime showpiece and talking point when entertaining guests. Those who painted rooms in blue were saying, “I can afford something which is not everybody’s capacity,” Zuchtriegel said.

recreation of a villa interior in Zaragoza, Spain

Mishael Quraishi, an archeology major, is one of several students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology working on the site. Using specially adapted night vision goggles and handheld scanners, they are studying the new find. Describing the room as “stunning,” she said it was really rare to see such high quantities of Egyptian blue in one concentrated area. It was “the first synthetically manufactured pigment in human history,” said Quraishi, 21, adding that it was made from a copper source “so brass filings could be an option.” After putting the elements together she said they were heated at incredibly high temperatures over many hours “and then this sort of glassy type material is formed with these Egyptian blue crystals in it.”

Sophie Hay, an archaeologist who works on the site, said the fact that frescos were painted when the plaster was wet meant “the pigments were sealed into the plaster.” Had they been painted on the surface, she said it was unlikely that the color would have been so vibrant. Elsewhere in the room, which is around 86 square feet in size, archeologists found building materials, suggesting a redecoration was planned. A collection of oyster shells was also discovered, likely waiting to be “finely ground to add to plaster and mortar,” the news release said. The excavation is part of a much larger project to help protect and preserve the excavated and unexcavated areas of Pompeii, which already include more than 13,000 rooms in 1,070 houses and apartments — deemed the largest dig in a generation.

In 2023, archaeologist announced that they had found a room with a kitchen shrine at Pompeii. Jonathan Amos of the BBC reported: Towards the back of the area so far excavated there is a wall that encloses three rooms. It's here that the removal of lapilli and ash has exposed more astonishing artwork. In the middle room, covered by a tarpaulin, is yet another elegant fresco. It shows the episode in the myth of Achilles where the legendary hero soldier with his unfortunate Achilles heel tried to hide dressed as a woman to avoid fighting in the Trojan War. In the third room, I pull back another tarp to reveal a magnificent shrine. Two yellow serpents in relief slither up a burgundy background. "These are good demons," says Alessandro. He points to a fresco further down the wall just above an opening to a box of some kind. "This room is actually a kitchen. They would have made offerings here to their gods. Foods like fish or fruits. The snake is a connection between the gods and the humans."[Source: Jonathan Amos, BBC, July 19, 2023]

Toilets in Ancient Rome

Toilet in Ephesus Turkey The Romans had flushing toilets. It is well known Romans used underground flowing water to wash away waste but they also had indoor plumbing and fairly advanced toilets. The homes of some rich people had plumbing that brought in hot and cold water and toilets that flushed away waste. Most people however used chamber pots and bedpans or the local neighborhood latrine. [Source: Andrew Handley, Listverse, February 8, 2013]

The ancient Romans had pipe heat and employed sanitary technology. Stone receptacles were used for toilets. Romans had heated toilets in their public baths. The ancient Romans and Egyptians had indoor lavatories. There are still the remains of the flushing lavatories that the Roman soldiers used at Housesteads on Hadrian's Wall in Britain. Toilets in Pompeii were called Vespasians after the Roman emperor who charged a toilet tax. During Roman times sewers were developed but few people had access to them. The majority of the people urinated and defecated in clay pots.

Ancient Greek and Roman chamber pots were taken to disposal areas which, according to Greek scholar Ian Jenkins, "was often no further than an open window." Roman public baths had a pubic sanitation system with water piped in and piped out. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse: “Rome has been praised for its advances in plumbing. Their cities had public toilets and full sewage systems, something that later societies wouldn’t share for centuries. That might sound like a tragic loss of an advanced technology, but as it turns out, there was a pretty good reason nobody else used Roman plumbing. “The public toilets were disgusting. Archaeologists believe they were rarely, if ever, cleaned because they have been found to be filled with parasites. In fact, Romans going to the bathroom would carry special combs designed to shave out lice. [Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016]

See Separate Article: TOILETS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024