BRONZE AGE

The Bronze Age lasted approximately from about 4,000 B.C. to 1,200 B.C. During this period everything from weapons to agricultural tools to hairpins was made with bronze (a copper-tin alloy). Weapons and tools made from bronze replaced crude implements of stone, wood, bone, and copper. Bronze knives are considerable sharper than copper ones. Bronze is much stronger than copper. It is credited with making war as we know it today possible. Bronze sword, bronze shield and bronze armored chariots gave those who had it a military advantage over those who didn't have it.

Copper was fairly plentiful and copper tools had been around for long before bronze ones. Therefore the key ingredient that made the age and innovation possible was tin.In case you forgot, the Stone Age and Copper Age preceded the Bronze Age and the Iron Age came after it. Gold was first fashioned into ornaments about the same time bronze was.

Typical Bronze Age food included round bread loaves, cheese, chick peas, garlic, goat, olives, and figs. People used stone and bronze sinkers, similar to ones they excavated, to weigh down fishing nets. Glass jars were made by wrapping liquid glass around a piece of clay that was dug out when the glass hardened. Ivory objects were painstakingly carved with drills propelled by a bow. Five-thousand-year-old bathing facilities were discovered in Gaza.

Metal was worked in a shaft furnace and shaped with an anvil and hammer, and ceramics created Bronze Age sites in Western Turkey were far superior to anything made by civilizations that preceded it. Also during the Bronze Age, glass jars were made by wrapping liquid glass around a piece of clay that was dug out when the glass hardened. Ivory objects were painstakingly carved with drills propelled by a bow.

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Bronze Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age Lives” by Anthony Harding (2021) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age War Chariots” Illustrated (2006) by Nic Fields Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations”

by Kristian Kristiansen and Thomas B. Larsson Amazon.com;

“The Iron Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024)

Amazon.com;

“The Luwian Civilization: The Missing Link in the Aegean Bronze Age” by Eberhard Zangger (2016) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age Metalwork: Techniques and Traditions in the Nordic Bronze Age 1500-1100 BC” by Heide W. Nørgaard (2018) Amazon.com;

The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean” (Oxford Handbooks) by Eric H. Cline Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age Illustrated Edition

by Cynthia W. Shelmerdine Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age” by by Anthony Harding and Harry Fokkens (2020) Amazon.com;

“European Societies in the Bronze Age” by A. F. Harding (2000) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Kanesh: A Merchant Colony in Bronze Age Anatolia” by Mogens Trolle Larsen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The End of the Bronze Age” by Robert Drews (1993) Amazon.com

“Collapse of the Bronze Age: The Story of Greece, Troy, Israel, Egypt, and the Peoples of the Sea” by Manuel Robbins (2001) Amazon.com;

Copper Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age

Archaeologists usually shy away from assigning fixed dates to the Neolithic, Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages because these ages are based on stages of developments in regard to stone, copper, bronze and iron tools and the technology used to make and the development of these tools and technologies developed at different times in different places. The terms the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age were coined by the Danish historian Christian Jurgen Thomsen in his Guide to Scandinavian Antiquities (1836) as a way of categorizing prehistoric objects. The Copper Age was added latter. In case you forgot, the Stone Age and Copper Age preceded the Bronze Age and the Iron Age came after it. Gold was first fashioned into ornaments about the same time bronze was.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “It is important to understand that terms such as Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age translate into hard dates only with reference to a particular region or peoples. In other words, it makes sense to say that the Greek Bronze Age begins before the Italian Bronze Age. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Classifying people according to the stage which they have reached in working with and making tools from hard substances such as stone or metal turns out to be a convenient rubric for antiquity. Of course it is not always the case that every Iron Age people is more than advanced in respects other than metalworking (such as letters or governmental structures) than the Bronze Age folk who preceded them.

“If you read in the literature on Italian prehistory, you find that there is a profusion of terms to designate chronological phases: Middle Bronze Age, Late Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age I, Middle Bronze Age II, and so forth. It can be bewildering, and it is damnably difficult to pin these phases to absolute dates. The reason is not hard to discover: when you are dealing with prehistory, all dates are relative rather than absolute. Pottery does not come out of the ground stamped 1400 B.C. The chart on the screen, synthesized from various sources, represents a consensus of sorts and can serve us as a working model.

Copper and the Copper and Bronze Ages

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Since the nineteenth century, archaeologists have categorized time periods in human history by the most advanced material used for tool-making and hence speak of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. Without copper, which can be alloyed with tin to produce bronze, there would have been no Bronze Age. Bronze was a revelation — it is extremely durable and holds an edge better than other materials available at the time. Beginning in the third millennium B.C., and especially during the second millennium B.C., copper was king and could make those who possessed it extremely wealthy and powerful. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when people began to exploit copper, but raw copper has been bent and shaped into decorative ornaments or arrowheads for at least 8,500 years. Copper smelting technology, a process in which raw ore is liquified so that it can be purified and poured into molds, dates to around 4500 B.C. This was followed, around 1,000 years later, by the development of the technology to create bronze. When copper is alloyed with tin, at a ratio of nine parts copper to one part tin, it produces bronze. This much harder and more durable metal enabled people to fashion nearly indestructible bronze tools such as axes, chisels, and swords that were instrumental in agriculture, shipbuilding, and warfare.

The search for particular metals has often led to exploration and, throughout history, civilizations have launched daring expeditions to obtain gold, silver, or other precious materials. The Bronze Age was the first great age of sailing, partially due to improved boatbuilding technology — thanks to the advent of bronze tools. Exploration was also fueled by the desire to obtain the copper needed to make more bronze. These circumstances made the island of Cyprus one of the most vital places in the Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age and beyond. For more than 2,000 years, until the fall of the Roman Empire, Cyprus was the most important producer of copper in the Mediterranean. Cyprus was so synonymous with the metal that the English word “copper” is derived from word cuprum and the phrase aes cyprium, meaning “metal of Cyprus.”

The earliest written reference to Cypriot copper is found on an eighteenth-century B.C. cuneiform tablet from the city-state of Mari in modern Syria that mentions a copper mountain in Alashiya, the Akkadian name for Cyprus. Proof of Cyprus’ near-total dominance of large-scale copper trading during the Late Bronze Age can be found in the Amarna Letters, a collection of fourteenth-century B.C. correspondence between the Egyptian pharaohs Amenhotep III (reigned ca. 1390–1352 B.C.) and Akhenaten (reigned ca. 1349–1336 B.C.) and foreign powers such as the Hittites and Babylonians. There are eight letters between Egypt and an unknown king of Cyprus, five of which mention shipments of copper from the island to Egypt. Each shipment would have totaled thousands of pounds, similar to the cargo of the Ulu Burun ship. Kings and leaders from around the Mediterranean sent their ships to Cyprus, many of which would have arrived at Hala Sultan Tekke.

Tin and Bronze Metallurgy

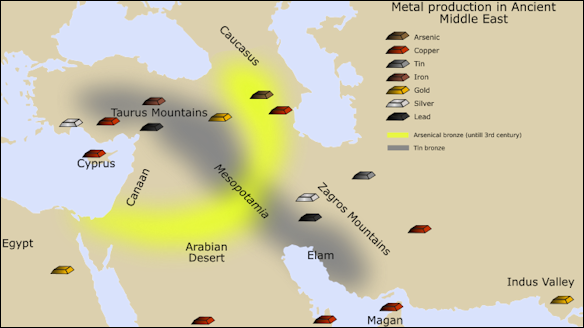

Copper tools had been around for long before bronze ones. Therefore the key ingredient that made the Bronze Age and innovation possible was tin. Copper was readily available over a large area. Much of it came from Cyprus. Tin was harder to find. It came mainly from mountains in Turkey and in Cornwall. Because tin was scarce and found in only localized regions, trade routes on which it was transported were set up. Tin itself became a highly profitable trade item. Taxes were placed on tin. Tolls were put in place on the trade routes.

Bronze is stronger than iron because it is an alloy of two other metals, making it denser and difficult to break with less friction. On the other hand, iron is a natural ore and less dense, and can be bent easily. Bronze can be melted easily, whereas iron needs a special furnace.

In all likelihood in present-day Turkey, Bronze Age Anatolians first got their tin from the Assyrians, who once referred to their Anatolian neighbors as "stupid,' in inscriptions from the second millennia B.C., because of the 100 percent profits they made by selling the Anatolians tin mined in the Hindu Kush mountains 1000 miles a way. Later the Anatolians found their own source of tin in the Tarsus mountains. Archaeologists discovered one six-square-mile area with nearly a thousand small tin mines. Some of the earliest mines, they say, were worked with stone tools by miners between the ages of 12 and 15. Later tin came from Cornwall. It was brought across the English Channel on boats and transported down the Somme, Oise and Seine Rivers into Europe.[Thomas Bass, Discover, December 1991]

Scientists believe, the heat required to melt copper and tin into bronze was created by fires in enclosed ovens outfitted with tubes that men blew into to stoke the fire. Before the metals were placed in the fire, they were crushed with stone pestles and then mixed with arsenic to lower the melting temperature. Bronze weapons were fashioned by pouring the molten mixture (approximately three parts copper and one part tin) into stone molds.

Sculptures made of copper, bronze and other metals were sometimes cast using the lost wax method which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a pieces of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burns and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. The metal sculpture was removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

World's First Bronze Age Culture — in Thailand

Ban Chiang ax head

Bronze artifacts have been discovered in northern Thailand, around the village of Ban Chiang, that were dated to 3600 to 4000 B.C., more than a thousand years before the Bronze Age was thought to have begun in the Middle East. The discovery of these tools resulted in a major revision of theories regarding the development of civilization in Asia.

The first discoveries of early Bronze Age culture in Southeast Asia were made by Dr. G. Solheim II, a professor of anthropology at the University of Hawaii. In the early 1970s, he found a socketed bronze ax, dated to 2,800 B.C., at a site in northern Thailand called Non Nok Tha. The ax was about 500 years older than the oldest non-Southeast-Asia bronze implements discovered in present-day Turkey and Iran, where it is believed the Bronze Age began. [Source: Wilhelm G. Solheim II, Ph.D., National Geographic, March 1971]

Non Nok Tha also yielded a copper tool dating back to 3,500 B.C.. and some double molds used in the casting of bronze, dating back to 2300 B.C, significantly older than similar samples found in India and China where it is believed bronze metal working began. Before Solheim it was thought that the knowledge of bronze working was introduced to Southeast Asia from China during the Chou dynasty (1122-771 B.C.). Solheim is sometimes called "Mr. Southeast Asia."

First Bronze Age Culture: the Ban Chiang Culture in Thailand

Ban Chiang site is located on he Khorat Plateau in northeastern Thailand. Among the discoveries made at a 124-acre mound site there were bracelets and bronze pellets (used for hunting with splits-string bows), and lovely painted ceramics dated to 3500 B.C. [Source: John Pfeiffer, Smithsonian magazine]

Most of the bronze made Ban Chiang is ten percent tin and 90 percent copper. This it turns out is ideal proportion. Any less tin, the metal fails to reach maximum hardness. Any more, the metal becomes too brittle and there is more of a chance it will break during forging. The Ban Chiang culture also developed bronze jewelry with a silvery sheen by adding 25 percent tin to the surface layers of the bronze at a heat of 1000̊F and plunging it quickly into water.

Iron was developed at Ban Chiang around 500 B.C. Ceramic funerary vessels dating between 3600 B.C. and 1000 B.C. contained the remains infants between one month and two years old. Others contain remains of rice, fish and turtles. The vessels come in a number of different styles and sizes. The largest are three feet tall. Some are painted with human, animal and plant figures as well as abstract circular and linear designs. Others have chord makings made by placing chord in wet clay.

Bronze Age China

According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art: The long period of the Bronze Age in China, which began around 2000 B.C., saw the growth and maturity of a civilization that would be sustained in its essential aspects for another 2,000 years. In the early stages of this development, the process of urbanization went hand in hand with the establishment of a social order. In China, as in other societies, the mechanism that generated social cohesion, and at a later stage statecraft, was ritualization. As most of the paraphernalia for early rituals were made in bronze and as rituals carried such an important social function, it is perhaps possible to read into the forms and decorations of these objects some of the central concerns of the societies (at least the upper sectors of the societies) that produced them. [Source: Department of Asian Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York:The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. metmuseum.org\^/]

“There were probably a number of early centers of bronze technology, but the area along the Yellow River in present-day Henan Province emerged as the center of the most advanced and literate cultures of the time and became the seat of the political and military power of the Shang dynasty (ca. 1600–1050 B.C.), the earliest archaeologically recorded dynasty in Chinese history. The Shang dynasty was conquered by the people of Zhou, who came from farther up the Yellow River in the area of Xi'an in Shaanxi Province. In the first years of the Zhou dynasty (ca. 1046–256 B.C.), known as the Western Zhou (ca. 1046–771 B.C.), the ruling house of Zhou exercised a certain degree of "imperial" power over most of central China. With the move of the capital to Luoyang in 771 B.C., however, the power of the Zhou rulers declined and the country divided into a number of nearly autonomous feudal states with nominal allegiance to the emperor. The second phase of the Zhou dynasty, known as the Eastern Zhou (771–256 B.C.), is subdivided into two periods, the Spring and Autumn period (770–ca. 475 B.C.) and the Warring States period (ca. 475–221 B.C.). During the Warring States period, seven major states contended for supreme control of the country, ending with the unification of China under the Qin in 221 B.C. \^/

“Although there is uncertainty as to when metallurgy began in China, there is reason to believe that early bronzeworking developed autonomously, independent of outside influences. The era of the Shang and the Zhou dynasties is generally known as the Bronze Age of China, because bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, used to fashion weapons, parts of chariots, and ritual vessels, played an important role in the material culture of the time. Iron appeared in China toward the end of the period, during the Eastern Zhou dynasty." \^/

“The earliest Chinese bronzes were made by the method known as piece-mold casting—as opposed to the lost-wax method, which was used in all other Bronze Age cultures. In piece-mold casting, a model is made of the object to be cast, and a clay mold taken of the model. The mold is then cut in sections to release the model, and the sections are reassembled after firing to form the mold for casting. If the object to be cast is a vessel, a core has to be placed inside the mold to provide the vessel's cavity. The piece-mold method was most likely the only one used in China until at least the end of the Shang dynasty. An advantage of this rather cumbersome way of casting bronze was that the decorative patterns could be carved or stamped directly on the inner surface of the mold before it was fired. This technique enabled the bronzeworker to achieve a high degree of sharpness and definition in even the most intricate designs." \^/

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; ERLITOU CULTURE (1900–1350 B.C.): CAPITAL OF THE XIA DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; SHANG DYNASTY LIFE AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com; BRONZE, JADE AND SHANG DYNASTY TECHNOLOGY AND ART factsanddetails.com

Metal production in Mesopotamia-era Middle East

Bronze Age Mesopotamia

The Bronze Age in Mesopotamia (roughly 3200 B.C. to 1000 B.C.) has been characterized as a time of vibrant economic expansion, when the earliest Sumerian cities and the first great Mesopotamian empires grew and prospered. John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “After thousands of years in which copper was the only metal in regular use, the rising civilizations of Mesopotamia set off a revolution in metallurgy when they learned to combine tin with copper -- in proportions of about 5 to 10 percent tin and the rest copper -- to produce bronze. Bronze was easier to cast in molds than copper and much harder, with the strength of some steel. Though expensive, bronze was eventually used in a wide variety of things, from axes and awls to hammers, sickles and weapons, like daggers and swords. The wealthy were entombed with figurines, bracelets and pendants of bronze. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, January 4, 1994]

Among the mysteries of ancient metallurgy include the question of how people first recognized the qualities of bronze made from tin and copper and how they mixed the alloy. For several centuries before the Bronze Age, metalsmiths in Mesopotamia were creating some tools and weapons out of a kind of naturally occurring bronze. The one used most frequently was a natural combination of arsenic and copper. The arsenic fumes during smelting must have poisoned many an ancient smith, and since the arsenic content of copper varied widely, the quality of the bronze also varied and must have caused manufacturing problems.

Scholars have yet to learn how the ancient Mesopotamians got the idea of mixing tin with copper to produce a much stronger bronze. But excavations have produced tin-bronze pins, axes and other artifacts from as early as 3000 B.C. In the Royal Cemetery at the ancient city of Ur, 9 of 12 of the metal vessels recovered were made of tin-bronze, suggesting that this was the dominant alloy by the middle of the third millennium B.C.

See Separate Article BRONZE, TIN, MINING AND TRADE IN MESOPOTAMIA factsanddetails.com

Bronze Age Palestine

Biblical and Jewish history begins during the Bronze Age (3300 - 1200 B.C.) in the Middle East. The birth of the Jewish people and the start of Judaism is told in the first five books of the Bible. Around 2000 B.C. God chose Abraham to be the father of a people who would be special to God, and who would be an example of good behaviour and holiness to the rest of the world. God guided the Jewish people through many troubles, and at the time of Moses, around 1300 B.C., he gave them a set of rules by which they should live, including the Ten Commandments. [Source: BBC]

Bronze bead necklace, 1800-1500 BC

According to Ancient Near East net: “The Early Bronze Age in the Levant [Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey] is most frequently characterised as the first great period of urbanism in the Near East, the material culture of the region reflecting a general trend towards living in urban settlements and social organisation along city lines. Scholars have therefore entitled this period variously as “the Emergence of Cities” [Mazar 1990:91] Social and cultural developments in the Levant at this time cannot be understood without appreciating their wider context in the regions as a whole; developments in both Egypt and Mesopotamia serve to frame those in the Levant. Thus, the second half of the fourth millennium B.C. witnessed the rise of truly complex civilisations in both river valleys, characterised by hierarchical government and administration, by the appearance of writing and literate societies, by irrigation and by large-scale public works. [Source: ancientneareast.net ***]

“Positioned centrally between them and serving as a land bridge, the Levant benefitted from the influence of both cradles of civilisation. Thus, the southern Levant (Palestine, Lebanon and southern Syria) developed clear connections with the Nile Delta region, later also with the Nile Valley; some limited Mesopotamian and Anatolian influence also filtered through via northern Syria. Northern Syria itself, of course, was positioned in close juxtaposition with the Upper Euphrates and Tigris river valleys, these serving to channel direct Mesopotamian influence into that region. Although lacking the riverine basis for urban civilisation present in both Egypt and Mesopotamia, being forced to rely on seasonal precipitation for agricultural water supply, the Levant was nonetheless able to follow their general trajectory by developing localised forms of urban culture in entirely different landscapes. ***

Wael Abu Azizeh wrote: The Early Bronze Age marked a watershed in the history of the southern Levant. This period represents a milestone in the march towards the urban era, expressing profound changes in the organization of societies. A series of technical innovations allowed the development of an agricultural economy. Irrigation, already used during the previous period, became the rule, and the introduction of the ox and plough improved yield and allowed the farming of new lands. The cultivation of olives and vines increased. Finally, the use of the donkey as a beast of burden and the spread of bronze tools facilitated this process of the intensification of production. [Source: Wael Abu Azizeh, “Atlas of Jordan”, p. 117-118, Open Edition Books, 2014]

Bronze Age Site Near Pompeii

One of the world's best preserved Bronze Age villages was buried under ash, mud and debris, near Pompeii, from a catastrophic eruption and pyroclastic flow of Mt. Vesuvius known to have taken place between 1800 and 1750 B.C. The site was discovered in 2001 near the town of Nola, 7.5 miles from Vesuvius, during routine checks before construction of a shopping center.

The Nola site contains molds of horseshoe-shaped building in reverse that are like casts made of victims of the Pompeii. There eruption occurred so quickly that people didn't have time to pack, and as a result items like drinking cups, jugs, cooking utensils, pots and hunting tools are believed to have been left pretty much where they were normally left in daily life.

Interesting objects found at the Nola site include a hat decorated with wild boar teeth and pot waiting to be cooked on a kiln. Bones and plants remains indicate they kept pigs, sheep, cows and goats and raised grain.

Nebra Sky Disk — Bronze Age Map of the Stars

The Nebra Sky Disc: is one of the most advanced and best-known artifacts of the Bronze Age. Named after the town where it was found in 1999 and dated to 1800 B.C., it surprised archaeologists, who couldn't believe a devise of such sophistication could be produced in the Bronze Age, a period better known for its swords, daggers and other weapons designed for battle. [Source: Jessica Orwig, Business Insider, January 21, 2015 +++]

The Nebra Sky Disc is the world’s oldest representation of a specific astronomical phenomenon. Found in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany, it is older than the 3,500-year-old star map on the ceiling of the tomb of Senmut near Luxor, Egypt. Made of bronze and gold, it is 30.5 centimeters (1 foot) diameter and weighs two kilograms (4.6 pounds). Jessica Orwig wrote in Business Insider: When it was first crafted, it would have shone a brilliant golden brown because the disc itself is made from bronze. But over time, the bronze corroded to green. The symbols are made of gold and didn't corrode. Although experts do not agree on what each symbol represents, for example the full circle could be the sun, full moon, or some type of eclipse, the overall message is clear that the symbols represent celestial objects. +++

The Nebra sky disc was so unlike any other artifact of its time that some archaeologists thought it was too good to be true. "When I first heard about the Nebra Disc I thought it was a joke, indeed I thought it was a forgery," Richard Harrison told the BBC in a documentary of the disc. Harrison is a professor of European prehistory at the University of Bristol and expert on the culture that inhabited Germany during the Bronze Age. "Because it's such an extraordinary piece that it wouldn't surprise any of us that a clever forger had cooked this up in a backroom and sold it for a lot of money." +++

See Separate Article: LATE STONE AGE AND BRONZE AGE SCIENCE: MATH, MEASUREMENT, MAPS AND THE NEBRA SKY DISC europe.factsanddetails.com

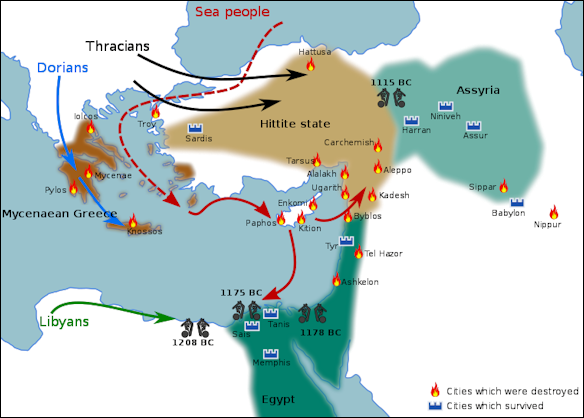

Late Bronze Age Collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse refers to a widespread societal collapse during the 12th century B.C.. associated with environmental change, mass migration, the destruction of cities and the demise of civilizations. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean, North Africa and Southeast Europe, and the Near East, particularly Egypt, eastern Libya, the Balkans, the Aegean, Anatolia, and, to a lesser degree, the Caucasus. It was sudden, violent, and culturally disruptive for many Bronze Age civilizations, and it brought a sharp economic decline to regional powers, notably ushering in the Greek Dark Ages. [Source: Wikipedia]

The robust economy of Mycenaean Greece, the Aegean region, and Anatolia that characterized the Late Bronze Age disintegrated and was replaced by the small isolated village cultures of the Greek Dark Ages, which lasted from around 1100 B.C. to the beginning of the Archaic age around 750 B.C.. The Hittite Empire of Anatolia and the Levant also. States such as the Middle Assyrian Empire in Mesopotamia and the New Kingdom of Egypt survived but in weakened forms. Other cultures such as the Phoenicians raised their profile and experienced increased autonomy and power as rivals such as Egypt and Assyria were sidelined.

A number of competing theories that attempt to explain the cause of the Late Bronze Age collapse have been proposed since the 19th century, with most involving the violent destruction of cities and towns. These include droughts, disease, volcanic eruptions, migrations of the Dorians, invasions by the Sea Peoples, economic disruptions resulting from increased ironworking, and changes in military technology and strategy that brought the decline of chariot warfare. Earthquakes had long been thought to be a cause but recent research suggests that earthquakes were not as determinant as previously believed. Following the collapse, gradual changes in metallurgic technology led to the subsequent Iron Age across Eurasia and Africa in the 1st millennium B.C..

Bronze Age Collapse

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024