BRONZE AGE MESOPOTAMIA

Bronze, baked clay Lamma goddess from Iraq, 1800 BC

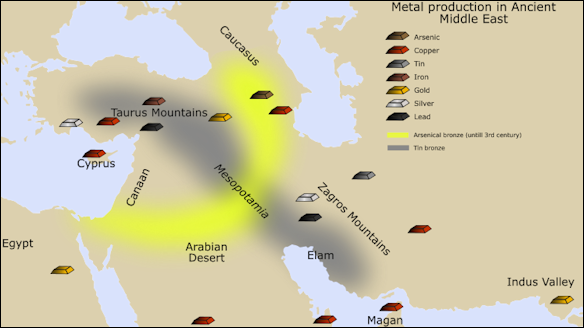

Bronze was first developed in Iran, various places in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, but Mesopotamian cultures invented many of the metalworking processing we still rely on today: smelting from ore, casting, alloying and soldering.Iron made possible sturdy plows and strong weapons. Crude iron was first used around 2000 B.C. Improved iron working from the Hittites became wide spread by 1200 B.C. Mesopotamia didn't have its own source of metal ores. It imported them from other places. Ores and precious metals were obtained through long distance caravan trade with places like southern Anatolia and present-day Jordan. One of the most effective weapons that was developed was the double headed ax head which could mounted socket-fashion onto a handle.

The Bronze Age in Mesopotamia (roughly 3200 B.C. to 1000 B.C.) has been characterized as a time of vibrant economic expansion, when the earliest Sumerian cities and the first great Mesopotamian empires grew and prospered. John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “After thousands of years in which copper was the only metal in regular use, the rising civilizations of Mesopotamia set off a revolution in metallurgy when they learned to combine tin with copper — in proportions of about 5 to 10 percent tin and the rest copper — to produce bronze. Bronze was easier to cast in molds than copper and much harder, with the strength of some steel. Though expensive, bronze was eventually used in a wide variety of things, from axes and awls to hammers, sickles and weapons, like daggers and swords. The wealthy were entombed with figurines, bracelets and pendants of bronze. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, January 4, 1994]

Among the mysteries of ancient metallurgy include the question of how people first recognized the qualities of bronze made from tin and copper and how they mixed the alloy. For several centuries before the Bronze Age, metalsmiths in Mesopotamia were creating some tools and weapons out of a kind of naturally occurring bronze. The one used most frequently was a natural combination of arsenic and copper. The arsenic fumes during smelting must have poisoned many an ancient smith, and since the arsenic content of copper varied widely, the quality of the bronze also varied and must have caused manufacturing problems.

Scholars have yet to learn how the ancient Mesopotamians got the idea of mixing tin with copper to produce a much stronger bronze. But excavations have produced tin-bronze pins, axes and other artifacts from as early as 3000 B.C. In the Royal Cemetery at the ancient city of Ur, 9 of 12 of the metal vessels recovered were made of tin-bronze, suggesting that this was the dominant alloy by the middle of the third millennium B.C.

The Bronze Age could not continue forever, scholars say, in part because tin was so hard to get, contributing to the expense of the metal alloy. The age came to an end around 1100 B.C., when iron, plentiful and accessible just about everywhere, became the most important metal in manufacturing.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence”

by P. R. S. Moorey (1999) Amazon.com;

“Tin in Antiquity: Its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall” by R.D. Penhallurick (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Bronze Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024) Amazon.com;

“Babylonia, the Gulf Region, and the Indus: Archaeological and Textual Evidence for Contact in the Third and Early Second Millennium B.C.” by Piotr Steinkeller Amazon.com;

“Magan – The Land of Copper: Prehistoric Metallurgy of Oman (The Archaeological Heritage of Oman) by Claudio Giardino Amazon.com;

“Ancient Magan: The Secrets of Tell Abraq” (In Depth Guides) Amazon.com;

“Looking for Dilmun” by Geoffrey Bibby (1996) Amazon.com;

“Dilmun and its Gulf Neighbours” by Harriet E. W. Crawford (1998) Amazon.com;

“Anatolia and the Bronze Age: The History of the Earliest Kingdoms and Cities that Dominated the Region” by Charles River Editors (2023) Amazon.com;

“Lithic Technology of Neolithic Syria” (BAR Archaeopress) by Yoshihiro Nishiaki (2000) Amazon.com;

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

“Economic Complexity in the Ancient Near East: Management of Resources and Taxation (Third-Second Millenium BC)” by Jana Mynářová (Editor), Sergio Alivernini (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History” by Nicholas Postgate (1994) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society of Ancient” Mesopotamia (Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records) by Steven Garfinkle and Gonzalo Rubio (2025) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in Babylonia: From Nabopolassar to Alexander the Great 626-331 BC”

by Muhammad A. Dandamaev , Victoria A. Powell, et al. (1984) “Slavery During The Third Dynasty Of Ur” by Bernard J Siegel (2007) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Valuable Metals in Ancient Mesopotamia

In the earlier period of Babylonian history, gold, silver, copper, and bronze were the metals which he manufactured into arms, utensils, and ornaments. At a later date, however, iron also came to be extensively used, though probably not before the sixteenth century B.C. The use of bronze, moreover, does not seem to go back much beyond the age of Sargon of Akkad; at all events, the oldest metal tools and weapons found at Tello are of copper, without any admixture of tin. Most of the copper came from the mines of the Sinaitic Peninsula, though the metal was also found in Cyprus, to which reference appears to be made in the annals of Sargon. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The tin was brought from a much greater distance. Indeed, it would seem that the nearest sources for it — at any rate in sufficient quantities for the bronze of the Oriental world — were in Afghanistan and Turkey. It is not surprising, therefore, that it should have been rare and expensive, and that consequently it was long before copper was superseded by the harder bronze.

Means, however, were found for hardening the copper when it was used, and copper tools were employed to cut even the hardest of stones. The metal, after being melted, was run into moulds of stone or clay. It was in this way that most of the gold and silver ornaments were manufactured which we see represented in the sculptures. Stone moulds for ear-rings have been found on the site of Nineveh, and the inscriptions contain many references to jewelry.

In the time of Nebuchadnezzar a cloak or overcoat used by the mountaineers cost only 4½ shekels, though under Cambyses we hear of 58 shekels being charged for eight of the same articles of dress, which were supplied to the “bowmen” of the army. Three years earlier 7½ shekels had been paid for two of these cloaks. About the same time ten sleeved gowns cost 35 shekels. Metal was more expensive. As has already been noticed, a copper libation-bowl and cup were sold for 4 manehs 9 shekels (£37 7s.), and two copper dishes, weighing 7½ manehs (19 pounds 8 ounces. troy), were valued at 22 shekels. The skilled labor expended upon the work was the least part of the cost.

Gold and Obsidian in Ancient Mesopotamia

The ancients determined the quality of gold by making a streak on it with a hard, black stone known as a touchstone, The brightness of the streak was an indication of the amount of gold. As early as 1500 B.C. the Mesopotamians learned how to purify gold by "cuppelation," in which impure gold was heated in a porcelain cup. The impurities were absorbed into the porcelain and pure gold remained.

The gold was also worked by the hand into beaded patterns, or incised like the silver seals, some of which have come down to us. Most of the gold was originally brought from the north; in the fifteenth century before our era the gold mines in the desert on the eastern side of Egypt provided the precious metal for the nations of Western Asia. A document found among the records of the trading firm of Murasu at Nippur, in the fifth century B.C., shows that the goldsmith was required to warrant the excellence of his work before handing it over to the customer, and it may be presumed that the same rule held good for other trades also. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The document in question is a guarantee that an emerald has been so well set in a ring as not to drop out for twenty years, and has been translated as follows by Professor Hilprecht: “Belakh-iddina and Bel-sunu, the sons of Bel, and Khatin, the son of Bazuzu, have made the following declaration to Bel-nadin-sumu, the son of Murasu: As to the gold ring set with an emerald, we guarantee that for twenty years the emerald will not fall out of the ring. If it should fall out before the end of twenty years, Bel-akh-iddina [and the two others] shall pay Bel-nadin-sumu an indemnity of ten manehs of silver.” Then come the names of seven witnesses and of the clerk who drew up the deed, and the artisans add their nail-marks in place of seals.

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology: “Three small and apparently unremarkable pieces of obsidian, found in the palace courtyard of the ancient city of Urkesh in modern-day Syria, are changing ideas about trade networks at the height of the Akkadian Empire’s power. Urkesh sits near a mountain pass by the border between the Bronze Age Hurrian and Akkadian empires—putting it in a natural position to be a trading center. [Source:Zach Zorich, Archaeology, December 19, 2012]

According to Ellery Frahm of the University of Sheffield and Joshua Feinberg of the University of Minnesota, decades of studies had shown that nearly all of the obsidian used in Urkesh and sites throughout Mesopotamia came from volcanoes in what is now eastern Turkey. Frahm, however, tested this by analyzing the magnetic properties of 97 pieces of obsidian found throughout the city and learned that three of the pieces came from a volcano located much farther away, in central Turkey. These pieces were dated to around 2440 B.C., about the time that Emperor Naram-Sin expanded the Akkadian Empire to its peak influence. Frahm believes that the Akkadians were expanding their trade networks into new territory. The three pieces of obsidian may have been from items traded along with more valuable goods, such as metals. According to Frahm, “It shows that they were tapping into a trade network at that time that they weren’t using before or after.” [Ibid]

Sources of Mesopotamia-Era Tin in Afghanistan and Turkey

One of the most enduring mysteries about ancient technology, Wilford wrote, “is where did the metalsmiths of the Middle East get the tin to produce the prized alloy that gave the Bronze Age its name. Digging through ruins and deciphering ancient texts, scholars found many sources of copper ore and evidence of furnaces for copper smelting. But despite their searching, they could never find any sign of ancient tin mining or smelting anywhere closer than Afghanistan. Sumerian texts referred to the tin trade from the east (thought to be Afghanistan). In the 1970s, Russian and French geologists identified several ancient tin mines in Afghanistan, where tin appears to be abundant . For many years that discovery seemed to resolve the issue of Mesopotamia's tin source. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, January 4, 1994]

It seemed incredible though that such an important industry could have been founded and sustained with long-distance trade alone to places like Afghanistan. But where was there any tin closer to home? After systematic explorations in the central Taurus Mountains of Turkey, an archeologist at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago has found a tin mine and ancient mining village 60 miles north of the Mediterranean coastal city of Tarsus. This was the first clear evidence of a local tin industry in the Middle East, archeologists said, and it dates to the early years of the Bronze Age.

The findings changed established thinking about the role of trade and metallurgy in the economic and cultural expansion of the Middle East in the Bronze Age. In an announcement made in January 1994, Dr. Aslihan Yener of the Oriental Institute reported that the mine and village demonstrated that tin mining was a well-developed industry in the region as long ago as 2870 B. C. She analyzed artifacts to re-create the process used to separate tin from ore at relatively low temperatures and in substantial quantities."Already we know that the industry had become just that — a fully developed industry with specialization of work," Dr. Yener told the New York Times, "It had gone beyond the craft stages that characterize production done for local purposes only."

Dr. Vincent C. Pigott, a specialist in the archeology of metallurgy at the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, said: "By all indications, she's got a tin mine. It's excellent archeology and a major step forward in understanding ancient metal technology." To Dr. Guillermo Algaze, an anthropologist at the University of California at San Diego and a scholar of Mesopotamian civilizations, the discovery is significant because it shows that bronze metallurgy, like agriculture and many other transforming human technologies, apparently developed independently in several places. Much of the innovation, moreover, seemed to come not from the urban centers of southern Mesopotamia, in today's Iraq, but from the northern hinterlands, like Anatolia, in what is now Turkey.

Speaking of the ancient tin workers of the Taurus Mountains, Dr. Algaze said: "It's very clear that these are not just rustic provincials sitting on resources. They had a high level of metallurgy technology, and they were exploiting tin for trade all around the Middle East." The mine, at a site called Kestel, has narrow passages running more than a mile into the mountainside, with others still blocked and unexplored. The archeologists found only low-grade tin ore, presumably the remains of richer deposits that had been mined out.

For this reason, Dr. James D. Muhly, a professor of ancient Middle Eastern history at the University of Pennsylvania, said he was skeptical of interpretations that Kestel was a tin mine. "They have identified the geological presence of tin," he contended. "Almost every piece of granite has at least minute concentrations of tin in it. But was there enough there for mining? I don't think they have found a tin mine." In her defense, Dr. Yener said: "His arguments are still based on an analysis of the mine and not the industry. He has to address the analysis of the crucibles." Although he was skeptical of Dr. Yener's claim to have found an ancient tin mine, Dr. Muhly praised her effort to find the sources of metals in the Middle East as "tremendously important archeology" because of the connection between the development and widening use of bronze and the emergence of complex societies, large urban centers, international trade and empires.

Mesopotamia-Era Tin-Mining Village in Turkey

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “On the hillside opposite the mine entrance, the archeologists found ruins of the mining village of Goltepe. Judging by its size, Dr. Yener said, 500 to 1,000 people lived in the village at any one time. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal and the styles of pottery indicated that Goltepe was occupied more or less continuously between 3290 and 1840 B. C. It began as a rude village of pit-houses dug into the soft sedimentary slopes and later developed into a more substantial walled community. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, January 4, 1994]

Scattered among the ruins were more than 50,000 stone tools and ceramic vessels, which ranged from the size of teacups and saucepans to the size of large cooking pots. The vessels were crucibles in which tin was smelted, Dr. Yener said, and they hold the most important clues to the meaning of her discovery and her answer to skeptics.

Slag left over from the smelting, collected last summer from inside the crucibles and in surrounding debris, contained not low-grade tin ore but material with 30 percent tin content, good enough for the metal trade. This analysis, including various tests with electron microscopes and X-rays, was conducted with the assistance of technicians from Cornwall, a region of England famous for tin mining since ancient times.

The tin-rich slag, Dr. Yener concluded, established beyond doubt that tin metal was being mined and smelted at Kestel and Goltepe. They could not have met all of the Middle East's tin needs in the Bronze Age, she said, but neither was all the tin imported, as had long been thought. By this time, the scientists realized the significance of all the stone tools and could reconstruct the methods of those ancient tin processors.

Mesopotamia-Era Tin Mining

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “The mining was done with stone tools and fire. Miners would light fires to soften the ore veins and make it easier to hack out chunks. Since the shafts were no more than two feet wide, the archeologists said, children may have been used for much of the underground work. This inference was reinforced by the discovery of several skeletons buried inside the mine; their ages at death were 12 to 15 years. Further examination should determine if they died of mining-related illnesses or injuries. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, January 4, 1994]

Once extracted, the tin ore, or cassiterite, was apparently washed, much the way Forty-Niners in the American West panned for gold in streams, separating nuggets from the rest. Many of the stone tools at the site were used to grind the more promising pieces of ore into smaller fragments or powder.

Then crucibles, set in pits, were filled with alternating layers of hot charcoal and cassiterite powder. Instead of using bellows, workers blew air through reed pipes to increase the heat of the burning charcoal. Tests indicated that this technique could have produced temperatures of 950 degrees Celsius and perhaps as high as 1,100 degrees (1,740 to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit), sufficient to separate the tin from surrounding ore. Droplets of tin were encased in molten slag. When this cooled, workers again used stone tools to crush the slag to release the relatively pure tin globules. Sometimes the slag was heated again to separate any remaining tin.

Metal production in the ancient Middle East

If this site is typical of ancient tin processing, Dr. Yener concluded, then archeologists may have overlooked other local sources of Bronze Age tin. They had been searching for the remains of large furnaces for tin smelting, much as had already been found for copper smelting, and had not suspected that a major tin-processing operation could be conducted successfully with fairly low grades of ore and in small batches in crucibles. In this manner, with hard work and many people, tin might even be recovered at relatively low temperatures.

The identity of these highland mining people is unknown, but their pottery betrays cultural ties to societies in northern Syria and Mesopotamia. The Taurus Mountains were known in the powerful cities of southern Mesopotamia as a rich source of metals, and Sargon the Great, founder of the Akkadian empire in the late third millennium B.C., wrote of obtaining silver there. Although Kestel was close to many ancient silver, gold and copper mines, no traces of copper were detected at the site, indicating that the processed tin was traded elsewhere for the production of bronze.

Trade or Colonialism Between Mesopotamia and Turkey?

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “On a limestone bluff overlooking the Euphrates in southeastern Turkey, a low mound spreads across several acres, blanketing the ruins of a settlement that bustled with life and trade in the late fourth millennium B.C. The ruins may tell a tale of how the world's first urban societies reached into the hinterlands for raw materials and thus started the earliest practice of colonialism.[Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, May 25, 1993]

Or it may turn out to be a somewhat different story. The first archeological excavations at the Turkish site of Hacinebi Tepe, begun last summer, have yielded surprising results. A preliminary examination of the stones, mud brick, ceramics and other artifacts suggests that the local people at Hacinebi may well have been trading with their supposed Mesopotamian masters as equals.

If so, these new findings do more than provide additional evidence of the widespread Mesopotamian presence among their neighbors to the north; they also raise serious questions about the nature of that relationship. Were they really there as colonialists? Perhaps they were only merchants in a widening network of long-distance trade, asserting little or none of the political, military or economic dominance usually associated with colonialism. They might even have been there, in some cases, as refugees.

Copper slag from Cyprus

Dr. Gil J. Stein, an anthropologist at Northwestern University who is directing the excavations, said the discoveries at Hacinebi are "provoking us to think of ancient colonization in a dramatically different way." Although other sites of Mesopotamian trading outposts and presumed colonies have been sampled before, this is the first one known to be superimposed on an existing local community. There is a well-preserved layer of artifacts of the people who lived there for generations before the Mesopotamians arrived. Immediately above it is a layer of indigenous artifacts and architectural remains mingled with clear evidence of a Mesopotamian presence.

Dr. William Sumner, director of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, said this was the first opportunity for archeologists to investigate the role of the indigenous societies in these trading centers and determine their relationship with the foreigners. Dr. Guillermo Algaze, an anthropologist at the University of California at San Diego who specializes in the colonialism of ancient civilizations, said: "This site has great potential. We will be seeing to what extent the enterprise was exploitative or more reciprocal, and seeing the social and economic impact it had on the locals."

Resource Exploitation and Uruk in Mesopotamia

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “A guiding hypothesis of ancient Mesopotamian studies has been that resource exploitation of foreign lands, not unlike modern colonialism, went hand in hand with the emergence of the first urban political states. This was happening in the midst of one of the most momentous transitions of antiquity, the beginning not just of history but also of civilization. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, May 25, 1993]

Some 700 miles down river from Hacinebi, in the years between 3500 and 3100 B.C., people living along the lower Euphrates and Tigris Rivers were cultivating the fertile plains with increasing success. Their irrigated fields were producing grain surpluses, and their flocks were shorn for a growing textile industry. People congregated in towns, notably Uruk, where they erected walls and imposing buildings and learned to keep account of their surpluses and industries by methods that would soon lead to writing, and so the beginning of history.

But these nascent city-states of southern Mesopotamia, in what is now Iraq, could not fill their need for metals and timber or their desire for semiprecious stones with which the elite could flaunt their rising status. For these goods, they had to look to the presumably less advanced but resource-rich societies on the plains and in the valleys of southwestern Iran and in the northern highlands of Syria and Turkey. Scholars described this outreach as the Uruk expansion.

figure on a Uruk vase

Writing in the June 1993 issue of American Anthropologist, Dr. Algaze compares Uruk's distant trading outposts to such modern examples as the Portuguese colony of Goa in India and the British colony of Hong Kong. The Uruk outposts, he said, "reflect a system of economic hegemony whereby early emergent states attempted to exploit less complex polities located well beyond the boundaries of their direct political control and that this system may be construed as imperialistic in both its extent and nature."

Recent excavations in the archeology of colonialism have revealed the ruins of several such Uruk outposts on major trade routes. One of the best documented is Godin Tepe, sitting astride the Khorasan Road, the most important east-west route crossing the Zagros Mountains of Iran. Settlers from the Uruk world appeared to have lived inside a fort that was surrounded by a local community. Their remains include some of the earliest evidence of beer and wine.

Since Godin Tepe must have existed far beyond Uruk's political control and presumably could not have survived for long without local acquiescence, archeologists have assumed this was not so much a colony as a trading post operated by Uruk merchants. One of the excavators, Dr. T. Cuyler Young Jr. of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, likened Godin to an early operation of the Hudson Bay Company, where merchants set up shop in remote places and bought and sold or traded goods with the indigenous population of Canada.

Archeologists think that Habuba Kabira had all the marks of a full-fledged colonial settlement. Situated on a bend of the upper Euphrates in Syria, just south of the Turkish border, this site appeared to be the hub of several nearby Uruk settlements. In the 1970's, German archeologists revealed Habuba Kabira to have been a fortified city with well-differentiated residential, industrial and administrative quarters apparently built as part of a single master plan. The architecture and artifacts leave no doubt that the inhabitants were colonists from southern Mesopotamia.

Hacinebi and Resource Exploitation in Mesopotamia

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “When Hacinebi was identified as a ruin from the period of Uruk expansion, archeologists saw it as an ideal site for addressing questions as to whether this was, in fact, an early form of colonialism. The site occupies a strategic position. It is only a few miles north of the ancient east-west river crossing point at the town of Birecik. It is also on the main north-south riverine trade route, linking the copper mines of Anatolia with the Mesopotamian heartland to the south. In the colonial hypothesis, places like Hacinebi served as outposts for procuring resources or as transshipment points for materials destined for the Mesopotamian cities. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, May 25, 1993]

Digging there in the summer f 1993, American and Turkish archeologists found a layer of buried ruins containing bowls, cooking pots and other ceramics that were all in the local Anatolian style. So there definitely had been a village at Hacinebi before the Mesopotamians came looking for copper and timber.

Hacinebi in southern Turkey

Moreover, Dr. Stein said, some of their artifacts could undermine the assumption by many scholars that Mesopotamian trade and colonization led to the emergence of complex societies in these resource-rich but relatively underdeveloped regions of Anatolia. A pendant made of soapstone, a product of southeast Iran, indicated that the villagers engaged in long-distance trade. Ruins of a monumental public building, the kind usually associated with more advanced urban centers, suggested that, as Dr. Stein said, these local people had evolved "a much more complex society than we've given them credit for up to now."

Immediately above the Anatolian village strata was a bed of beveled rim ceramics in the Mesopotamian style and the remnants of buildings on a raised stone terrace, an unmistakable change in architecture. Mesopotamian and Anatolian pottery are mixed together; in one place, the foreign pottery is found on one side of a wall and the local pottery on the other.

Dr. Stein said there are two ways of interpreting these findings. "One possibility is that a small group of Mesopotamians were living and trading inside the local settlement," he said. "Or perhaps the local people had come in close contact with the Mesopotamians and were emulating them."

Also uncovered at the site were chunks of bitumen, a tar substance that was widely used by the Uruk culture for sealing and waterproofing ceramic containers. Bitumen is rarely found outside ancient Mesopotamia, and Dr. Stein said its use as a sealant suggests that goods were being received at Hacinebi from the outside world.

The presence of embossed clay seals, Dr. Stein said, indicates that Hacinebi was somehow involved in administering the movement of goods. The seals were applied to the doors of storerooms and to ceramic storage jars to certify a transaction, mark the contents and prevent tampering. At least one of the seals was clearly stamped in the local manner, suggesting that local people, and not just Mesopotamians, participated in an official capacity in this trading system.

"Several lines of evidence suggest that existing models of the Uruk expansion may have underestimated the role of the local cultures," Dr. Stein said. "First, the locals were already relatively developed before contact with the Uruk culture. Second, they were not pawns in the trading system, but more or less equal partners. So you see, the classic colonial model doesn't really work." In any event, the Uruk influence at Hacinebi lasted no more than 175 years, ending around 3100 B.C. Soon the Uruk culture would decline and be succeeded by the even more robust and innovative Sumerian civilization of the third millennium B.C.

Problems with Resource Exploitation Theory in Mesopotamia

“Even before the Hacinebi discoveries,” Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “some scholars were taking shots at the hypothesis that the Uruk expansion was the manifestation of an early empire and its faraway colonies. Not the least of the problems with the hypothesis, according to Dr. Susan Pollock, an anthropologist at the State University of New York at Binghamton, is the absence of trade goods in the archeological record. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, May 25, 1993]

In an article last year in The Journal of World Prehistory, Dr. Pollock dismissed possible explanations that the goods were perishable or that as objects of trade, they would not have remained at the trading posts. It is assumed that textiles might have been a staple of trade from Uruk to the hinterlands, and so would have decayed over time. But the trade goods moving back to Uruk were supposedly such nonperishable materials as metal and semiprecious stones.

True, copper was showing up in Mesopotamia about the time that Uruk styles were showing up at Hacinebi. But to Dr. Pollock it is "difficult to conceive of a situation in which the traders or colonists would not have taken advantage of the opportunities to exploit the situation for as much as they could get away with." If they had skimmed off some exotic goods, where were they in the ruins? The place to look, Dr. Pollock said, was in graves at the Uruk outposts. But few graves have been found so far.

Even more emphatic in opposition is Dr. Gregory A. Johnson, an anthropologist at Hunter College in New York, who said the colonial hypothesis "simply doesn't hold water." Scholars tend to forget, Dr. Johnson said, that this was a period of severe population decline in many southern Mesopotamian cities, including Ur, Eridu and Nippur. "When you're losing half your population, something nasty must be going on," he said, and the collapse could be behind the sudden appearance of Mesopotamian settlements in the highlands. It was not an empire expanding, he said, but disintegrating.

As a leading exponent of the idea that colonialism sprang almost inevitably from the rise of the first political states, Dr. Algaze is not backing down from his imperial interpretation of the Uruk expansion. Indeed, he has expanded his brief to show that similar expansionary dynamics had led four other early civilizations — the Sumerians, Teotihuacan in Central Mexico, the Harappan culture in the Indus River basin of Pakistan and the predynastic Egyptians — to reach out for resources and territory.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024