HINDU FUNERAL CUSTOMS

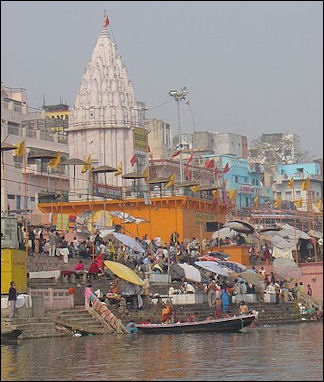

busy cremation ghat in Varanasi Most Hindus cremate their dead. For Hindus, this is done ideally by a river so that deceased's souls can have a swift passage to desirable realms in the afterworld. The deceased are typically cremated on a pile of logs, although burial may be used by those who are very poor. Members of the Lingayat sect and extremely saintly figures may be buried in a sitting position. The elaborate, traditional Hindu death ceremony lasts for 13 days.

There is little mourning when a Hindu dies because they believe that once a person is born he or she never dies. Often there is little crying. Some Indians have said this is because the point of a funeral is to show respect not sadness. Other say it is because Hindu believe the dead are off to a world far better than the one they left behind.

Traditionally women have not been allowed at cremations because they might cry. Their tears like all bodily fluids are regard as pollutants. Women are not supposed to enter the cremation area or even watch what goes on inside it. This includes close relatives and family members. They may help lay out the body at home but carrying the body, gathering the wood and lighting the fire are all considered man's work.

In Uttar Praddesh, burials are often be marked by two clay vessels hanging in a fig tree. Water drips from one of the vessels through a small hole at the bottom, while a lamp burned in the other. Both jars are broken on an appointed day by a Brahman priest. The priest receives religious alms for his services in the name of the dead person. Each family is expected to honor dead ancestors through commemorative annual feasts. [Source: Teferi Abate Adem, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Websites and Resources on Hinduism: Hinduism Today hinduismtoday.com ; India Divine indiadivine.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Oxford center of Hindu Studies ochs.org.uk ; Hindu Website hinduwebsite.com/hinduindex ; Hindu Gallery hindugallery.com ; Encyclopædia Britannica Online article britannica.com ; International Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/hindu ; The Hindu Religion, Swami Vivekananda (1894), .wikisource.org ; Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press academic.oup.com/jhs

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hindu Funeral Rites: Antyeshti Sanskar” by Sadhu Shrutiprakashdas and Pranati Parikh Amazon.com ;

“Garuda Purana And Other Hindu Ideas Of Death, Rebirth And Immortality”

by Devdutt Pattanaik Amazon.com ;

“The Sacred Book of Death - Hindu Spiritism, Soul Transition and Soul Reincarnation”

by Dr. L. W. de Lawrence Amazon.com ;

“The Hindu Temple and Its Sacred Landscape” (The Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies)

by Himanshu Prabha Ray Amazon.com ;

“Hindu Rites And Rituals: Origins And Meanings” by K V Singh Amazon.com ;

“Hindu Rites, Rituals, Customs & Traditions” by Prem P. Bhalla Amazon.com ;

“Durga Puja,Lakshmi Puja,Saraswati Puja,Navratri Puja : Hindu Home Puja Book: Complete Ritual Worship Procedure” by Santhi Sivakumar Amazon.com ;

“Shiva Beginner Puja” by Swami Satyananda Saraswati and Shree Maa Amazon.com ;

"An Introduction to Hinduism" by Gavin Flood Amazon.com ;

“Hinduism for Beginners - The Ultimate Guide to Hindu Gods, Hindu Beliefs, Hindu Rituals and Hindu Religion” by Cassie Coleman Amazon.com ;

"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger; Amazon.com ;

“Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization” by Heinrich Zimmer (Princeton University Press, 1992) Amazon.com

Funeral Procedures

In keeping with the Hindu custom of swift cremation, bodies are cremated within 24 hours after death, if at all possible, even if close relatives can not attend the funeral. Ideally cremation is done within 12 hours after death, or at the very latest before sundown on the next day if death occurs late in the afternoon. The first person families of the dead usually call is the "ice wallah" in the nearby market. Normally the eldest son carries out the funerary rites. He lights the funeral pyre after first placing a burning stick in the mouth of the deceased. One of the primary reasons that Hindus wish for a son is that only sons can carry out funeral rites. It is possible to substitute another relative for a son but this is generally regarded as much less effective.

According to the BBC: “ It is preferable for a Hindu to die at home. Traditionally a candle is lit by the head of the deceased. The body is then placed in the entranceway of the house with the head facing south. The body is bathed, anointed with sandalwood, shaved (if male) and wrapped in cloth. It is preferable for cremation to take place on the day of death. The body is then carried to the funeral pyre by the male relatives and prayers are said to Yama, the god of death. Sometimes the name of God (Ram) is chanted. While doing this the pyre is circled three times anti-clockwise. This is usually done by the male relatives of the family, lead by the chief mourner. [Source: BBC |::|]

“On the funeral pyre the feet of the body are positioned pointing south in the direction of the realm of Yama and the head positioned north towards the realm of Kubera, the god of wealth. Traditionally it is the chief mourner who sets light to the pyre. This is done by accepting flaming kusha twigs from the Doms' who are part of the Untouchable Hindu caste responsible for tending to funeral pyres. The body is now an offering to Agni, the god of fire. |::|

“After cremation the ashes are collected and usually scattered in water. The River Ganges is considered the most sacred place to scatter ashes. Similarly, Benares (the home of Siva, Lord of destruction) is a preferred place of death because it takes the pollution out of death and makes it a positive event. Anyone who dies here breaks the cycle of life and achieves moksha (enlightenment or release).” |::|

The process of organizing the rituals that surround the cremation and funeral s can be difficult. “There’s no pricing schedule,” one Indian woman living London told Fortune, “nobody checks the educational background and qualifications of the people who deliver these services.” [Source: Ambika Behal, Fortune, August 20, 2016]

See Separate Articles: HINDU VIEWS ON DEATH factsanddetails.com; HINDU CREMATIONS factsanddetails.com; WIDOW BURNING (SATI) IN INDIA factsanddetails.com

Importance of Having the Body in Hinduism and India

Goutam Ghosh died near the summit of Mt. Everest and his family, community and even the state government in West Bengal went through great lengths and expense to bring his body back John Branch wrote in the New York Times: “There were three major reasons the Ghosh family desperately wanted Goutam’s body returned. The first was emotional. The idea that he lay near the summit of Everest, alone, exposed to the elements, left to serve as a tragic tourist marker for future climbers, was nearly too much to bear. And they wanted answers about what happened. Maybe his body could provide those answers. Maybe that video camera around his neck, if it was still there and still worked, held clues. Maybe there were memory cards from his camera in his pockets or backpack. Maybe a message for the family. Something. [Source: John Branch, New York Times, December 19, 2017]

“The second was religious. Hindus believe the body is merely a temporary vessel for the soul. Once the soul is severed from the body through cremation, it is reincarnated in another body. Like most in West Bengal and across India, the Ghoshes were devoutly Hindu. To them, closure required a cremation, and all the ceremonies that came with it.

“The third reason, as important as the others, was financial. Legally, in India, Ghosh was considered a missing person. Only when a body was produced, or seven years had passed, would the Indian government issue a death certificate, which the Ghosh family needed to gain access to his modest bank accounts and to receive financial death benefits like life insurance and the pension he had earned as a police officer.

Hindu Preparations for Dying

wood for cremation When death is imminent the dying person is taken from his bed and laid on the ground, facing south, on a layer of sacred grass. Then a series rites is carried out, presided over by the oldest son or another male relative. These include: 1) the vratodyapana (“completion of the vows”), in which all the vows that the dying has not yet complected are magically completed and ten gifts are made in the name of the dying in one last effort to earn merit ; 2) savraprayascitta (“atonement for everything”), in which is a cow is donated to Brahma to absolve the dying of all his sins and guarantee he or she is carried over the river into heaven; and 3) a ritual bath in holy water from the Ganges.

When death occurs verses from the Vedas should be recited in the ear of the dying. Behavior at the end of one’s life and last thought before dying are believed to be very important in determining how an individual will be reincarnated. Thus a great deal of care goes into making sure a person is well cared before they die and after. This is achieved by creating a calm atmosphere and reading Vedic scriptures and reciting mantras so the soon-to-be-dead can earn as much merit as possible. It is believed that if a person’s final thoughts are angry or disturbed he may end up in hell.

Hindu Mourning Period

Hindus believe that the soul exists in a ghost-like state for 10 to 30 days until it is ready to move on to the next stage. For ten to 30 days after a funeral, depending on the caste, the mourners are secluded from society while daily ceremonies. with special ones on 4th, 10th and 14th days, are performed to provide the souls of the deceased with a new spiritual body needed to pass on to the next life. These rites involve offering rice balls and vessels of milk to the deceased. Mourners are expected to refrain from cutting their fingernails, combing their hair, wearing jewelry or shoes, reading sacred texts, having sex and cooking their own food. If not properly performed the soul may become a ghost that haunts its relatives.

After the tenth day, the soul move on and the mourners are regarded as purified. The 12th day after a death has special meaning for Hindus. It is when the soul passes on to the next life. The day is marked by special prayers. A caste dinner is given on the 12th or 13th day after special “ritual of peace” is performed to mark the ending of the mourning period . The ritual involves the chanting of mantras while making a fire and placing four offerings in the fire and touching a red bull.

The full mourning period lasts two weeks to a year depending on the age of the deceased and the closeness of the relationship to him or her. At the end of a mourning period for his mother a son shaves his head. Sometimes this is done in a river and the hair carried away is a "sign of renewal." When the morning period is complete the eldest son become the head of the family and the wife of a deceased man becomes a widow.

There are restrictions on eating salt, lentils, oil and a number of other foods during the mourning period. Restrictions on the eldest son are even stricter. He often can eat only one meal a day consisting of rice, ghee and sugar and must shave all the hair from his body and conduct hours of rituals and take periodic ritual cold baths for a period of mourning that lasts up to one year.

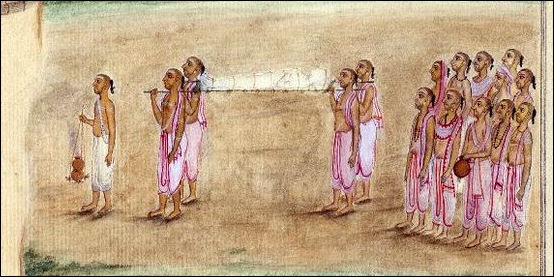

Hindu funeral

Rites with offerings known as shaddha are periodically held after a person has died to nourish the soul in the afterlife. The rites are often performed once a year and feature a feast with a plate of food of food offered to the dead. Hindu believe the living must feed the dead living in the World of the Fathers. If the ancestors are properly taken care of they will reward the living with prosperity and sons. The shaddha is thought to day back to the Aryans. It is viewed as a meeting between the living and the dead. The souls of the dead who are nor properly buried are thought live outside the World of Fathers as ghosts that torment their relatives until they are there. custom ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Hindu Reincarnation, Caste and Inheritance

Many Hindu communities believe in reincarnation, which says that the soul can be reincarnated for an unknown number of rebirths. The nature of the reincarnation is determined by the balance of one's sins and good deeds in past lives — karma. This belief provides the justification for the inequities of the caste system: It is believed that one cannot change their caste in this life, but may do so in the next reincarnation. It is also believed that particularly wicked individuals may be reincarnated as animals. [Source: Paul Hockings, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Inheritance was given to this who were obligated to perform shraddha. Since only males can perform the shraddha only they could receive an inheritance. Men without sons could adopt a boy or appoint a daughter, if he had one, to give birth to a boy. Since one male can only serve one the grandson or adopted son gave up the right to perform shraddha to his immediate family. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

The concept of shraddha was an Aryan idea supplanted by the idea of reincarnation but many of its beliefs remain. Village women are given their inheritance at birth because they are not a son.

Ending the Practice of Dumping Dead Children into Rivers

Jeremy Page wrote in The Times: “As soon as Nawal Kishore approached his boat the dogs began to circle. They had watched him countless times before, dropping the children’s corpses into the Yamuna river in Delhi — a stinking slick of sewage, rubbish and chemical waste — to comply with Hindu custom. They had seen, too, how they could catch the bodies that slipped their weights and floated to the surface, or dig up the ones he buried on the bank. “For 16 years I’ve been doing this. My father did it before me. Who knows how many children we’ve given to the Yamuna?” said Mr Kishore, 42, perching on the edge of his boat. [Source: Jeremy Page, The Times, July 1, 2008]

Four years into India’s economic boom, this is how the city of 14 million people still disposes of its dead children — 1,000 a month, according to Mr Kishore’s records. Until May this was one of the Indian capital’s dirtiest secrets, a practice that was rarely talked about in private, let alone in public or the media. Now, however, a single Indian businessman is leading a campaign to ban the custom and force the Government to open dedicated crematoriums and cemeteries for children.

“His quest began when his one-year-old nephew died in April. The family took the corpse to the local state crematorium, where the Hindu faithful burn their dead on funeral pyres and then sprinkle the ashes in the Yamuna — one of India’s five holy rivers. But the priests refused to accept the child because he was under 3 and should therefore be immersed in the river whole. Staff at a second crematorium said the same thing.

“Both directed him to the patch of river bank where Mr Kishore and his ancestors have plied their trade since 1951. There he found what is officially not a river but an open drain, since it carries only sewage, rubbish and industrial effluent. Shocked by the filthy black water, Mr Sharma opted to have his nephew buried on the banks — although they were littered with bottles, condoms and human excrement. Even as Mr Kishore was digging the grave, stray dogs dug up another and tore apart a child’s corpse, Mr Sharma said. He covered his nephew’s grave with rocks and hired a private guard. The guard started to run away at night because he was scared.

“A Delhi court ruled in his favour last month by ordering the city’s 62 crematoriums — all state-owned — to accept children of all ages. Since then, city authorities have put up signs to that effect in all crematoria, and more by the river forbidding the immersion of children. The Government says it is planning to allocate land for children’s cremation and burial. But Mr Sharma and other activists remain sceptical.

Diving for Dead Bodies

M.N. Parth wrote in the Los Angeles Times: In a remote north Indian village, Ashu Malik’s name and phone number are written in big red letters on a small shed along a serene canal. For a quarter-century, it has been his job to recover bodies that have fallen into the canal. When someone in a nearby district goes missing, Malik often hears a knock at the door. Police officers, investigative agencies and families have all sought the 38-year-old’s help in dealing with accidents or suicides. [Source: M.N. Parth Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2017]

Built more than 60 years ago, the Bhakra Main Line canal, which runs through four states in northern India, is a tranquil sight that is often tainted by the odor of dead bodies. The canal’s sluice gate, where the water branches in two directions, is located in Khanauri, which is where the bodies often turn up. Malik grew up alongside the canal in the state of Haryana. He was 12 when he discovered his skill for diving. “A woman was washing her clothes at the canal when she lost her balance,” the bearded Malik recalled. “She cried for help and I jumped in as others watched on. I saved her life and a local newspaper carried the news with my photograph.”

Malik was excited when the police officer in charge rewarded him for his bravery with 50 rupees, less than $1 in today’s money. “That was five months’ rent in 1991-92,” he said with a smile. “My father was a poor man. He could not believe it. He thought I had stolen something.” A few weeks later, the officer summoned Malik again and offered him 80 rupees to fish out a body. The young boy was scared; the corpse was bloated and decomposed. “But I dived in, tied a rope around its leg and completed the job,” he said.

By 1998, Malik was the leader of a team with four divers. He now works with 140 volunteers across four states, all men, and offers their services via a website. He and his team have fished out tens of thousands of bodies, he said, including instances when buses have crashed into the canal with dozens of passengers aboard. He opened a ledger where he has meticulously listed victims by name and date, as well as hundreds of local newspaper clippings.

Malik’s village of Khanauri is in the agrarian state of Punjab, which has a population of just under 28 million. With a farm crisis, drug use and unemployment weighing on people, Malik said suicides are on the rise. His team finds roughly 10 bodies every day, he said, most of them suicides. So many family members of missing people visit Khanauri in search of closure that, about a decade ago, a local charity built a guesthouse. A full-time police officer sits there now to gather the details of every new missing persons case and circulate them by WhatsApp to Malik’s team. Based on the location, divers are identified. They strip down to their underwear and swim without any protective gear.

For all his fame, however, Malik lives in poverty. As a child he neglected his studies to focus on diving, because the money he made helped his father, a widower, support him and his three sisters. Malik lives at the guesthouse, paying about $50 in rent a month. He wishes that authorities would hire him and pay him a fixed salary. He has a robust folder of bravery citations, but no money to pay for the education of his four children, ages 3 to 13. His wife died of cancer two years ago.

His only income comes from families who ask him to recover bodies, but most are debt-ridden — often the reason the person committed suicide in the first place. It costs about $200 to deploy divers across many parts of the canal, he said. But if a family is poor, he won’t ask for money. “I am happy with their blessings,” he said.

Sometimes he finds valuables that were dropped into the canal, pawning them to raise about $100 every month. Occasionally, police officials have accused him of stealing items off the bodies. Malik denies this, believing the police resent him because by finding bodies, he exposes the incompetence of the authorities. “I have been interrogated several times,” he said bitterly. “But they have not found anything against me. Villagers have always stood by me.” “I believe I have been helpful and honest while doing what I am doing,” he went on. “But it is not enough to ensure an education for my kids. Am I asking for too much?”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia “ edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024