HINDU CREMATIONS

Gandhi cremation There are about 3.14 million deaths a year in India. Most people are cremated. For the part most cremations are still done the way they have been done for centuries, by following the final life ritual called antyesti, outlined in the Grihya Sutras. The average cost of a funeral is $12 to $71.

Cremation is an extremely important ritual for Hindus. They believe it releases an individual’s spiritual essence from its transitory physical body so it can be reborn. If it is not done or not done properly, it is thought, the soul will be disturbed and not find its way to its proper place in the afterlife and come back and haunt living relatives. Fire is the chosen method to dispose of the dead because of its association with purity and its power to scare away harmful ghosts, demons and spirits. The fire god Agni is asked to consume the physical body and create its essence in heaven in preparation for transmigration. Cremations are still associated with sacrifices. The god Pushan is asked to accept the sacrifice and guide the soul to its proper place in the afterlife.

Not everyone is cremated. Holy men, lepers and people with small pox have traditionally been buried, with holy men traditionally buried in a vertical position preserved with salt. Small children under two are not cremated because their soul does not need purifying. In many cases today they are not buried but are taken to the middle of the Ganges or another sacred river and dropped to the river bottom with a weighed stone. Families who can not afford the wood for cremation sometimes throw unburned corpses in the Ganges. In some cases an effigy is burned to symbolize cremation. Few people are buried. These are victims of suicide, murder, or some other kind of violence who, it is believed, have souls that will not rest, no matter what is done to the corpse.

Cremation has remained common, possibly because cemeteries are a waste of space. New electric crematoriums are becoming more popular. They are more efficient and cleaner, and save precious fuel and forests.

See Separate Articles: HINDU VIEWS ON DEATH factsanddetails.com; HINDU FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; WIDOW BURNING (SATI) IN INDIA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Hinduism: Hinduism Today hinduismtoday.com ; India Divine indiadivine.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Oxford center of Hindu Studies ochs.org.uk ; Hindu Website hinduwebsite.com/hinduindex ; Hindu Gallery hindugallery.com ; Encyclopædia Britannica Online article britannica.com ; International Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/hindu ; The Hindu Religion, Swami Vivekananda (1894), .wikisource.org ; Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press academic.oup.com/jhs

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hindu Funeral Rites: Antyeshti Sanskar” by Sadhu Shrutiprakashdas and Pranati Parikh Amazon.com ;

“Garuda Purana And Other Hindu Ideas Of Death, Rebirth And Immortality”

by Devdutt Pattanaik Amazon.com ;

“The Sacred Book of Death - Hindu Spiritism, Soul Transition and Soul Reincarnation”

by Dr. L. W. de Lawrence Amazon.com ;

“The Hindu Temple and Its Sacred Landscape” (The Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies)

by Himanshu Prabha Ray Amazon.com ;

“Hindu Rites And Rituals: Origins And Meanings” by K V Singh Amazon.com ;

“Hindu Rites, Rituals, Customs & Traditions” by Prem P. Bhalla Amazon.com ;

“Durga Puja,Lakshmi Puja,Saraswati Puja,Navratri Puja : Hindu Home Puja Book: Complete Ritual Worship Procedure” by Santhi Sivakumar Amazon.com ;

“Shiva Beginner Puja” by Swami Satyananda Saraswati and Shree Maa Amazon.com ;

"An Introduction to Hinduism" by Gavin Flood Amazon.com ;

“Hinduism for Beginners - The Ultimate Guide to Hindu Gods, Hindu Beliefs, Hindu Rituals and Hindu Religion” by Cassie Coleman Amazon.com ;

"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger; Amazon.com ;

“Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization” by Heinrich Zimmer (Princeton University Press, 1992) Amazon.com

Early Cremations in India

Balinese widow burning in 1597 It is not clear how and why the custom of cremation evolved. By the time the earliest Hindu texts were written around 1,200 B.C. it was already an established custom. There is some archeological evidence that in the distant past burial was the norm and later cremation with a secondary burial became common place and this gave way to cremation, the dominant custom today.

From the time of the Rig Veda, which contains passages possibly written as far aback as 2000 B.C., Hindus have cremated the dead although small children and ascetic were sometimes buried and low caste members sometimes buried their own. One passage from the Rig Veda addressed to Jataedas!, the fire that burns that corpse, goes.

O Jataedas! When you thoroughly burn this [departed person],

Then may you hand him over to the pitris [i.e. heavenly fathers]!

When he [the deceased] follows thus [path] that leads to a new life,

May he become on that carries out the wishes of the gods

Sometimes animals were sacrificed at the funerals. Another passage from the Rig Veda reads:

O Jatavedas! May you burn by your heat the goat that is youre share!

May your flame, may your bright light burn that goat;

Carry this [departed soul] to the world if this who do good deeds

By means of youre beneficent bodies [flames]!

It is not known why the custom of cremation was adopted, Some have suggested 1) it is a method of purification, of releasing the soul from a polluted body; 2) it symbolizes the transitory nature of life, of destruction and rebirth; or 3) it eliminated the body as a health risk and doesn’t take up valuable land.

Preparations Before a Cremation

Family members have traditionally prepared the body of the deceased. Before cremation, the body is wrapped and washed, with jewelry and sacred objects intact, in a plain sheet. A red cloth is used for holy people. Married women are buried in their wedding dress and an orange shroud. Men and widows have a white shroud.

Later the body is dressed in fine clothes and the nail are trimmed and thumbs are tied together while scriptures are read. Often some leaves of the Tulasi tree and few drops of sacred water are placed in the mouth of the deceased. In ancient times the funeral bed was made from rare wood and antelope skin. These days it is made from bamboo or common kinds of wood and no animal skins are used.

While the corpse is in the house no family member or neighbor can eat, drink ir work. Hindus don’t like it when non-Hindus touch the corpse so an effort is made make sure that any non-Hindus who touch a copse at a hospital are wearing rubber gloves. In the old days the body was disemboweled, fecal matter was removed and the abdominal cavity was filled with ghee or some other pure substance. But this is no longer done. Autopsies are regarded as extremely offensive. Some customs vary according to caste, cultural background and region from which the funeral participants are from.

After the body has been prepared it is carried by male relatives on a flower-draped bamboo bier to the cremation ghats. There is no coffin. Sometimes if the deceased died on an inauspicious day the body is taken out of the house through a hole in a wall rather than the doorway. Male relatives that carry the shrouded body chant “Rama nama satya hai,” the name of the God of Truth. The eldest son is in the lead. He has been purified in a special ritual and carries a fire kindled in the home of the deceased. The fire is carried in a black earthen pot. If the procession is near the Ganges the body is immersed in the river before being placed on the funeral pyre.

Hindu Cremation

Cremations take place at special cremation grounds. The body is anointed with ghee (clarified butter). Men are sometimes cremated face up while women are cremated face down. The funeral pyre is often made of corkwood and offerings of camphor, sandalwood and mango leaves. A typical pyre is made of 300 kilograms or so of wood. Rich families sometimes pay for the entire pyre to be made up of sandalwood. In Kerala mango wood is often used. because wood is scarce and expensive. Some poor families use cow dung instead of wood. In any case, wood is usually piled on the pyre until only the head is visible. Mantras are recited to purify the cremation grounds and scare away ghosts. Offerings are made to Agni, the fire god, at an altar.

Common fire for poor Possessions of the deceased are often placed on the pyre. Death is believed to be contagious and it is thought that contact with these possessions could cause death. Sometimes a wife climbs on the pyre and climbs off before the fire is lit, an acknowledgment of suttee (wife-burning) custom without actually carrying it out. Sometimes goats is circled around the pyre three times and given to Brahmins. This symbolizes an ancient cow sacrifice.

The eldest son or youngest son — often with his head shaved and wearing a white robe out of respect — usually lights the fire. Before this is done the shroud of the deceased is cut and the body smeared with ghee and a brief disposal ceremony is led by a priest. The son lights a torch with the fire from the black earthen pot and takes the torch and a matka (clay pot with water) and walks around the pyre seven times. Afterwards the matka is smashed, symbolizing the break with earth. The torch is used to light the funeral pyre: at the foot of a deceased woman or at the head of a deceased man. The Brahmin priest reads sacred verses from the Garuda Purana, speeding the dead person’ soul to the next life.

Burning of Dead and the Corpse That Coughed

As the pyre burns the mourners jog around the fire without looking at it, chanting "ram nam sit hair: ("God's name is truth") in the inauspicious clockwise direction. The priest intones; “Fire, you were lighted by him, so may he be lighted from you that he may in the regions of celestial bliss.” It takes about three or four hours for a body to burn.

The fire is left to burn itself out. In that time the body is transformed to ashes, and it is hoped the skull explodes to release the soul to heaven. When the fire has cooled, if the skull has not cracked open spontaneously, the oldest son splits it in two. If the cremation is done near the Ganges the bones and ashes are thrown into the Ganges.

Few tears are shed. The cremation of Indira Gandhi was broadcast around the world. After witnessing her cremation presided over by her son Rajiv, one visiting dignitary asked him , "Could you really do that to your mother?" On the third day after the funeral the cremation bones are thrown into a river, preferably the Ganges, and for ten days rice balls and vessels of milk and libations of water are offered to the deceased.

In 1931 the International Herald Tribune reported that an Allahabad woman was snatched from the leaping flames of a funeral pyre after she had been pronounced dead by the village medical authorities in a remote Bengal village. The woman, according to the village chief’s assistant’s account, gave birth to a child while in a hysterical fit. Later, she was declared dead by a physician who was summoned to her bedside. In accordance with the Indian custom, cremation was arranged and the following morning the body was ceremoniously carried to the ghat and placed on top of the funeral pyre. It was not until after the fire had been lighted that relatives observed that the woman was breathing, Shrill cries attracted the attention of the men in charge and they noticed that the woman coughed. Despite the smoke and flames, rescuers climbed to the top of the pyre and carried her to waiting friends.

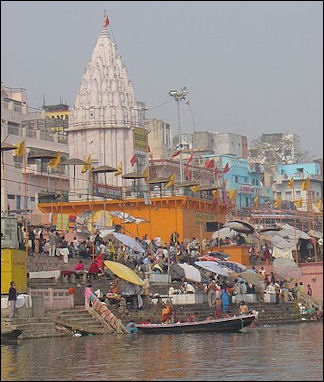

Varanasi, the Lovely Place to Die

Jim Lo Scalzo wrote in U.S. News and World Report, “For a city where people come to spend the last moments of their lives, Varanasi feels eternally—and exquisitely—alive. The holiest city in Hinduism is a place without vanity, where millions of pilgrims come each year to exhibit the most private moments of their religious life: to pray, to wash away their sins, to die. Here the road to salvation is a river, the Ganga Ma, or Mother Ganges, and few places on Earth offer such dramatic and public displays of elemental worship. [Source: Jim Lo Scalzo, U.S. News and World Report, Nov. 16, 2007 +]

“Though the Ganges is an actual deity, its heightened status in the Hindu pantheon is grounded in the material; the river irrigates one of the largest and most densely populated watersheds in the world. This is the Indian heartland, where rich alluvial soil gave rise to the region's first civilization and now helps feed the entire country. Hindus thus venerate Ganga Ma as a giver of life—and, confoundingly, as a means of liberation from it. +\

“To die in Varanasi, on the river's sacred banks, is to free oneself from samsara, the seemingly endless cycle of death and rebirth; it enables one to forgo further reincarnations and achieve moksha, or spiritual liberation. Moksha is not a place but a goal, one similar to Buddhist enlightenment, an emancipation from temporal desires and all the suffering that goes with them. Moksha is what every Hindu desires most, a supreme realization of the self, and there is no faster route than these waters. +\

“A bend in the river. But why here? Why, on a river that is more than 1,500 miles long, did Varanasi emerge where it did? "Thousands of years ago the spot was the nexus of some important trade routes," says John Hawley, professor of religion at Columbia University's Barnard College. "It was also unusual in that the river, which flows southeast, here makes a sharp turn and flows north, as if it were looking back at its origins." +\

Manikarnika cremation ghat in Varanasi

"The northern direction was considered very auspicious," concurs Travis Smith, a Varanasi expert and assistant professor at the University of Florida's Department of Religion. "And it was significant to Varanasi's development," because it allowed worshipers and temples on the western side of the river to directly face the rising sun. According to Smith, Varanasi soon "became associated with wandering ascetics. As a trading center, it was a good place to get alms." +\

Today, Varanasi's cremation ghats are still at the city's heart—literally and metaphorically—and still face the rising sun. Several thousand bodies a month are consumed by fires that, day and night, never go out. Barefoot men use bamboo poles to rotate the blackened bodies, and the resulting smoke hangs above the river complex like a thin blue veil. The bone and ash that remain are shoveled into the river. It is not uncommon to see uncremated corpses in the river as well—the bodies of infants who are still considered pure and not in need of cremation, floating alone in the caramel-colored water. +\

“The river's unsightly shade of brown isn't caused by silt alone. Though the Ganges begins as glacial melt high in the Himalayas, it is soon sullied with pollution. By the time its water reaches Varanasi, the Ganges seems less a river than a roux, a toxic mix of raw sewage (the river's fecal level is 1.5 million times India's safe level for drinking), industrial chemicals, and corpses. Yet for the millions of pilgrims who come to Varanasi annually, pilgrims who collect, bathe in, and, yes, drink this water, the river's austere origins are still enough to assuage such mortal concerns.

Beyond the waterfront, Varanasi's interior is a dark and dirty labyrinth, one so narrow that a sleeping cow can block your passage. The air is heavy. Bouquets of patchouli incense compete with India's signature odors—car exhaust and coal fires. Ocher-robed ascetics—garlands of marigolds around their necks, tridents in their hands—wander these passageways, as do hustlers, dope pushers, and beggars. As the primordial home of Shiva, that most fertile of Hindu gods, the city is cluttered with phalluses, both stone and real. The former emerge from temples and sidewalks like concrete posts, the latter hang from sadhus, or Hindu holy men, whose only dress, if you can call it that, is the ashes from the cremation ghats spread over their bodies like powder. It seems an impossible amalgam, a city that is revered for, and made beautiful by, its facilitation of death. And yet that's precisely the case for Varanasi. Death becomes it.” +\

Hindu Cremations in Varanasi

Bodies waiting for cremation Varanasi (Banaras, or Benares) is the place every Hindu hopes to be when he or she dies so they can escape the cycle of rebirth and death. If a person dies in the Ganges or has Ganges water sprinkled on them as they breath their last breath it is believed they achieve absolute salvation, escaping the toil of reincarnation to be transported to Shiva's Himalayan version of heaven.

Cremations have been taking place in the Ganges for thousands of years. Perhaps a 100,000 cremated bodies are thrown in the Ganges every year. In Varanasi, funeral parties wait for their turns on the steps of the ghats (cremation grounds). Bundles carried through the streets are often corpses. On the roads leading to Varanasi you will often see shrouded corpses placed on the roofs of vehicles like surfboards or kayaks. There is even a caste that specializes in sifting through the ashes and mud at the bottom of Ganges for rings and jewelry.

The processions with the corpse to the ghat are often accompanied by singing, dancing and drumming. They often have a festive atmosphere. Relatives chant “Rama nama satya hai.” The body is immersed once in the Ganges and then anointed with ghee (clarified butter), lashed to a platform and wrapped in bright yellow fabric. The pyre is lit with a flame from a temple. Periodically the embers of the fire pyre are poked by boys with six foot poles to keep the fire burning.

Descriptions of Cremation in Varanasi

Describing the burning ghats at Varanasi in 1933, Patrick Balfour wrote: "Through stagnant water, thick with scum and rotting flowers, we drifted towards the burning ghats, where a coil of smoke rose into the air from a mass of ashes no longer recognizable as a body. One pyre, neatly stacked in a rectangular pile, had just been lit, and the corpse swathed in white, protruded from the middle." [Source: Eyewitness to History, edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

"An old man surrounded with marigolds, sat cross-legged on the step above. Men were supporting him and rubbing him with oil and sand, he submitted limply to their ministrations, staring, wide-eyed, towards the sun...'Why are they massaging him like that?' I asked the guide...'Because he is dead.'"

wood for cremation "And then I saw them unfold him from his limp position and carry him towards the stack of wood. Yet he looked no more dead than many of the living around him. They put him face downwards on the pyre, turned his shaved head towards the river, piled wood on top of him and set it alight with brands of straw, pouring on him butter and flour and rice and sandalwood."

"The ceremony was performed with detatchment and a good deal of chat, while uninterested onlookers talked among themselves. When I drifted back, some ten minutes later, the head was a charred bone and a cow was placidly munching the marigold wreathes...The body takes about three hours to burn. Sometime less if more wood is added. The richer a family is the more wood they can afford. While its burning Dom teenager poke at the logs as if it were a campfire. Sometimes cows stand around the fire to get warm.”

“When the wood is burned to ashes, the breastbone f the deceased is often still intact. It is given to the eldest son who tosses it in the Ganges. After the family of the deceased leaves Dom children descend on the on the ashes looking for coins, nose studs or gold teeth.”

Reporting from Varanasi in 2007, Bruce Wallace wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Cremation fires crackle all day long on the chipped concrete steps of this riverside holy city, the blazes spewing ash and flakes over the mourners who crowd its famous piers. Sweating, bare-chested men stoke the funeral pyres, squinting against the sting of smoke as they lug and stack the bundles of logs needed to burn the procession of Hindu dead. And when the bodies are incinerated and the families have taken away the ashes of their loved ones, the men sweep the residue into the Ganges River. The detritus of death, mingling with life. [Source: Bruce Wallace, Los Angeles Times, September 3, 2007 ^^]

“Devout Hindus regard cremation as an essential rite that frees the soul from the body, enabling its journey to the next level. But with India's Hindu population of about 800 million ensuring a massive number of open-air cremations, there is a growing awareness that this adherence to religious orthodoxy carries a toll for the temporal world.” ^^

Doms and Hindu Cremation

The cremations in Varanasi and other places are performed by the Doms, a subcaste that makes their living burning bodies for cremations for a fee that ranges considerably depending on the wealth of the family. The Doms are a caste of Untouchables. Touching a corpse after death is viewed as polluting and thus only Untouchables are designated to do this kind of work. So terrible is this work, it is said, Doms are expected to weep when their children are born and party when death releases them from their macabre responsibilities.

busy Ghat In addition to charging money for performing the cremations the Doms also take a cut from the exorbitantly-priced wood sold near the ghats. The Doms in Varanasi have become very wealthy from their trade and some Indians have accused them of "extortion" because of the high prices they charge and the fact they often take money from poor families that struggle to pay for the cremations. Because they are the only ones allowed to perform the cremations, the Doms have established a monopoly that allows them to charge very high prices. When customers can't pay the full price the Doms hold back the supply of wood and bodies end up half-burned.

In the 1980s the Dom Raja controlled the ghats and the supply of wood used to burn the 35,000 or so bodies brought to Ganges in Varanasi for cremations. The Raja did not perform a cremation unless he was paid in advance the $45 or so for the wood, and often he demanded an extra payment to guarantee the soul would be liberated. These payments, some claimed, made him the richest man in Varanasi. [Source:Geoffrey Ward, Smithsonian magazine, September 1985]

Describing an encounter with the Dom Raja, Geoffrey Ward wrote in Smithsonian magazine: "The Dom Raja himself sat cross-legged on a string bed inside his darkened room. Eight hangers on sat at his feet around a little table on which rests a brass tumbler and half-empty bottle of clear homemade liquor. The Dom Raja was immensely fat, nearly naked and totally bald. His thick fingers were covered with big gold rings. When he spoke he slurred his words. I had not brought him a handsome gift, he finally mumbled, so he saw no reason to speak further with me."

After the Hindu Cremation

After the cremation fire is extinguished the focus of the funeral ritual changes to purifying the relatives of the deceased who are looked upon as ritually impure from their exposure to the corpse. If he hasn’t done so already the eldest son or presiding male relative shaves his head and wears a white robe after the cremation. On the day after pyre was lit he often pours milk over pyre.

After the cremation family members wash themselves in water in trenches north of the pyre and pass under a cow yoke propped up by branches, and offer a prayer to the sun. They then walk off led by youngest son and don’t look back. In the first stream they encounter they bath while shouting out the name of the deceased. Afterwards they place rice and peas on the ground to confuse ghosts and then walk to a pleasant place and relate stories about the deceased. When they arrive at home they touch several objects — a stone, fire, dung, grain, a seed, oil and water — in proper order to purify themselves before they enter their houses.

Remains in the Ganges

After the cremation the bones and ashes of the deceased are thrown into the Ganges. Even those who are not cremated near the Ganges have their ashes placed there. Rock guitarists Jerry Garcia and George Harrison are among those who had their ashes scattered in the Ganges. In the old days thousands of uncremated bodies were thrown into the Ganges during cholera epidemics, spreading the disease and producing more corpses.

Today only bones and ashes are supposed to be scattered in the river. Even so the cremation process, especially among those who can not afford the large amount of wood needed to incinerate the entire body, leaves behind a lot of half burned body parts. To get rid of the body parts special snapping turtles are bred and released in the river that are taught to consume dead human flesh but not bother swimmers and bathers. These turtles consume about a pound of flesh a day and can reach a size of 70 pounds.

In the early 1990s, the government built an electric crematorium on the side of the Ganges, in part to reduce the amount of half-burned bodies floating down the river. Even after the system was introduced most people still preferred the traditional method of cremation.

the yucky mess along much of Ganges around Varanasi

80 Bodies in Ganges From Apparent ' Water Burial'

Water burials are banned in India, but the practice still takes place because of beliefs among some Hindus that unwed girls should not be cremated, and that a water burial ensures that she will be reborn into the same family. This is believed to have been the fate of 80 bodies that surfaced in northern India in 2015. Poor families who cannot afford cremations also prefer to deposit the deceased in bodies of water such as the Ganges.

Parth M.N. wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Authorities in northern India said that some 80 bodies that surfaced in the Ganges River this week – many of them children – had been given traditional water burials and were not victims of foul play. Villagers in Pariyar, 50 miles from the city of Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh state, noticed the floating bodies after dogs and vultures were seen in the area, prompting local officials to investigate. “The dead bodies were buried in the water,” said Saumya Agarwal, the district magistrate of Unnao, which includes Pariyar. “They resurfaced as the water levels receded.” [Source: Parth M.N., Los Angeles Times, January 14, 2015]

The bodies were badly decomposed, indicating they had been in the water for a substantial time, officials said. Authorities conducted DNA tests and cremated the bodies in the soil according to the wishes of local residents, Agarwal said.“Water burials are discouraged because of environmental reasons but it is true that they have not stopped entirely – especially in the case of unwed girls,” Agarwal sad.

Environmental Damage from Hindu Cremations

Bruce Wallace wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “It takes a lot of wood to burn a body: The demand for funeral pyres strips the country of more than 50 million trees annually, according to some estimates. Cremations also release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. And the body parts sometimes dumped into rivers and streams add further toxicity to water that is already badly polluted. [Source: Bruce Wallace, Los Angeles Times, September 3, 2007 ^^]

"We have come to a stage where if we don't come up with a solution for dealing with the dead, we are going to affect the survival of the living," said Anshul Garg, director of Mokshda, a nonprofit group in New Delhi that is campaigning for an environmentally friendly approach to cremation. ^^

“In traditional Hindu cremations, the body is placed atop a pile of wood. The corpse is then covered with more wood and burned in the open air. Mokshda says this method requires as much as 880 pounds of wood to burn a single corpse (though the wood porters in Varanasi say the amount is closer to 600 pounds), a process that can take as long as six hours.” Yet the realities of the outside world intrude even on this holiest of Hindu cities. Yadav recalled the wood shortage of 2005, when scarcity meant the bodies backed up on the ghats while they waited for supplies. The price of wood is 50% higher than it was five years ago.” ^^

green cremation

Green Cremation

Wallace wrote in the Los Angeles Times, Mokshda's alternative is the "Green Cremation System," a cremation bier it developed 15 years ago and has been tinkering with since. The organization believes it has perfected its design, saying it can burn a body using a mere 220 pounds of wood in a third of the time. [Source: Bruce Wallace, Los Angeles Times, September 3, 2007 ^^]

“Wood is integral to Hindu cremation rites, a symbolic connection between the body and the earth, which is why the first layer of wood is laid on the ground. The Mokshda system's innovation is to place that first layer of wood on a raised metal grate, allowing for better air circulation. A chimney is placed over the pyre to cut heat loss. "We have improved the flow of air and where there is a proper flow of air, your combustion efficiency increases," Garg said. "This is not a new technological gizmo. It's a simplicity, like improving the efficiency of a wood stove." ^^

“Mokshda's system has made only tiny inroads so far. It has 12 units of its latest model, which on average costs about $30,000, in operation, with orders for 80 more in the pipeline. But the potential demand is enormous. Mokshda says it has identified 800 crematoriums across India as possible users. The Delhi metropolitan area alone has about 350 crematoriums, their flaky residue occasionally drifting over nearby neighborhoods. ^^

“Mokshda says its system can succeed where the electric one failed because it allows Hindus to perform traditional rituals. The challenge is to convince devout Hindus that using less wood does not break with orthodoxy. Even Garg acknowledges that it will be a while before Mokshda's cremation bier is welcome in a place such as Varanasi.” ^^

“And in his office on Varanasi's back streets, Kameshwar Upadhyay, a Hindu scholar known for his strict views, looked thoughtfully at photographs of the Mokshda system and didn't dismiss it as heretical. He acknowledged that India is groaning under the stress of an expanding population. And if he was not about to welcome the Mokshda system in the spiritual center of Varanasi, he thought it might not be a bad idea in big cities. ^^

"There is a provision that after death, a person needs to be completely de-linked from this Earth, and fire helps in that goal," Upadhyay said. "But there are changing situations that come to us on Earth and we have to work out compromises for that. As long as mukhagni and kapal kriya can be followed, there should be no problem. "Fire," he said, "is fire."” ^^

Resistance to Green Cremation

Wallace wrote: But the Mokshda system faces two big obstacles to acceptance. For one thing, improving cremation methods is a low priority for cash-strapped municipalities facing a host of public health issues. An even greater obstacle is the resistance of traditionalists who don't want to mess with a matter as sensitive as the fate of a loved one's soul. "We have changed other rituals — marriage, eating habits, clothing — but rituals around death are the hardest to change," Garg said. "People are hesitant to talk about death; there is a fear. So they say they'll stick with what they've been following through the ages." [Source: Bruce Wallace, Los Angeles Times, September 3, 2007 ^^]

Munshi Ghat in Varanasi

“The government also has largely failed to get Hindus to sign on to environmentally friendly cremations. Beginning in the 1960s, municipal governments began installing electric or gas-fueled crematoriums, offering to dispose of bodies at a fraction of the cost of traditional cremations, which can be $50 to $75, depending on the quality and amount of wood used. But most Hindus have balked at this option, saying that oven-like crematoriums prevent them from carrying out important rituals such as the mukhagni, in which a fire is lighted in the body's mouth, and the kapal kriya, in which the corpse's skull is shattered by a blow from a bamboo stick to release the soul. ^^

“It is mostly unclaimed corpses that are burned in electric and gas crematoriums, stigmatizing them as being for the poorest of the poor. "It's a good method — there's less pollution because you are not dumping lumps of flesh into the river — but we don't get many bodies," said Panchdev Singh, 47, the operator of Varanasi's electric crematorium. There are no bodies awaiting Singh's attention. One of his two machines is out of order, and business has fallen off since 2000, when the municipality raised the price to about $12. "Now the only people who come here are the very poor or the ones brought in by the police," Singh said. ^^

"I doubt it would be a hit here," said Dinesh Yadav, 21, who has taken over the family wood business, running a gang of 10 porters for cremations on Varanasi's ghats, or riverside steps. "People want to do it the Hindu way. Older people, especially, will never settle for being burned with less than the required quantity of wood." "A time will come when we'll probably have to move to a new way," he said.: ^^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except dirty Ganges and green cremation, Al Jazeera

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia “ edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024