WIDOWS IN INDIA

Although a man may grieve for his deceased wife, a widow may face not only a personal loss but a major restructuring of her life. Becoming a widow in India is not a benign or neutral event. A man's death, particularly if it occurs when he is young, may be attributed to ill fortune brought upon him by his wife, possibly because of her sins in a past life. With the death of her husband, a woman's auspicious wifehood ends, and she is plunged into dreaded widowhood. The very word widow is used as an epithet. As a widow, a woman is devoid of reason to adorn herself. If she follows tradition, she may shave her head, shed her jewelry, and wear only plain white or dark clothing. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Widows of low-ranking groups have always been allowed to remarry, but widows of high rank have been expected to remain unmarried and chaste until death. In earlier times, for child brides married to older men and widowed young, these strictures caused great hardship and inspired reform movements in some parts of the country. *

In past centuries, the ultimate rejection of widowhood occurred in the burning of the Hindu widow on her husband's funeral pyre, a practice known as sati (meaning, literally, true or virtuous one). Women who so perished in the funeral flames were posthumously adulated, and even in the late twentieth century are worshiped at memorial tablets and temples erected in their honor. In western India, Rajput lineages proudly point to satis in their history. Sati was never widespread, and it has been illegal since 1829, but a few cases of sati still occur in India every year. In choosing to die with her husband, a woman evinces great merit and power and is considered able to bring boons to her husband's patrilineage and to others who honor her. Thus, through her meritorious death, a widow avoids disdain and achieves glory, not only for herself, but for all of her kin as well. *

By restricting widow remarriage, high-status groups limit restructuring of the lineage on the death of a male member. An unmarried widow remains a member of her husband's lineage, with no competing ties to other groups of in-laws. Her rights to her husband's property, traditionally limited though they are to management rather than outright inheritance, remain uncomplicated by remarriage to a man from another lineage. It is among lower-ranking groups with lesser amounts of property and prestige that widow remarriage is most frequent. *

See Separate Articles: HINDU VIEWS ON DEATH factsanddetails.com; HINDU FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; HINDU CREMATIONS factsanddetails.com;

Sati (Widow Burning)

“Sati” ("widow burning") is a Hindu ritual in which a wife kills herself by throwing herself onto her husband's funeral pyre after her husband's death. It was regarded a s act of self-sacrifice to help both in the wife and husband and their children in their next lives. The practice is named after Sita, a manifestation of Shiva’s wife and wife of the legendary hero Rama. Sita is regarded as the ideal wife because of unquestioning loyalty to her husband. In the Ramayana she proves her chastity to her husband Rama by walking through a fire. The Ramayana says "Without my lord, my life to bless, where would be heaven or happiness.”

In western India, Rajput lineages proudly point to satis in their history. Sati was never widespread, and it has been illegal since 1829, but a few cases of sati still occur in India every year. In choosing to die with her husband, a woman evinces great merit and power and is considered able to bring boons to her husband's patrilineage and to others who honor her. Thus, through her meritorious death, a widow avoids disdain and achieves glory, not only for herself, but for all of her kin as well. [Source: Library of Congress]

Sati (or “sutee”) means “virtuous woman.” It is supposed to be voluntary and never demanded of women with young children. By going trough with it, it is believed, a woman not only expunges her sins but also those of her husband: helping to ensure them millions of years of bliss together in heaven. Hindu scripture related to sati reads: “O mortal, this woman (your wife), wishing to be joined to you in a future world is lying by your corpse; she has always observed the duties of a faithful wife. Grant her your permission to abandon this world (of the living), and relinquish your wealth to your descendants.”

Today wives symbolically lay down on the pyre with their deceased husbands but jump down before the fire is lit. But sometimes the pressure put on a widow is so great she has little choice but to go along with the real thing. Women who perish in the funeral flames are posthumously adulated, and even now are worshiped at memorial tablets and temples erected in their honor.

Before the British government outlawed sati in 1829 there were more than 500 incidents of widow burning a year in Bengal alone. In 1813, there were 275 reported cases within 30 miles of Calcutta. In some cases women were beaten unconscious before they were thrown on the fire by their in-laws who wanted to get their hands of their husband's estate. Women generally did not climb on the pyre willingly. Relatives often tried them up or drugged them. Even then they often jumped off the pyre and tried to run away. They were almost always caught and thrown back on. In many cases they were placed under logs or something else to prevent them from escaping.

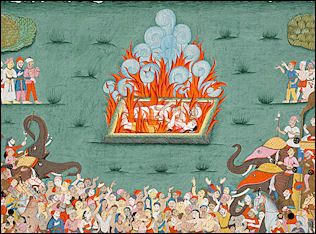

Preparations for Sati in 1650

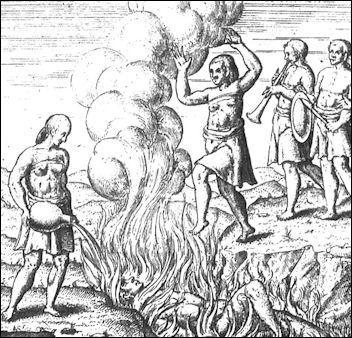

Balinese widow burning in 1597

Describing preparations for sati in 1650, Jean Baptiste Tavernier wrote: "It is also an ancient custom of the idolaters in India that on a man dying his widow can never remarry; as soon, therefore, as he is dead she retires to weep for her husband, and some days afterwards her hair is shaved off, and she despoils herself of all ornaments with which her person was adorned; she removes her arm and leg bracelets which her husband had given her...as a sign she was to be submissive and bound to him. [Source: “Eyewitness to History”, edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

"This miserable condition causes her to detest life and prefer to ascend a funeral pile to be consumed alive with the body of her deceased husband, rather than be regarded by all the world for the remainder of days with opprobrium and infamy. besides this the brahmans induce women to hope that by dying in this way, with their husband, they will live again with them in some other world with more glory and more comfort.

"It is only childless widows which can be reproached for not having loved their husbands if they have not had the courage to burn themselves after their death, and to whom this want of courage will be free the remainder of their lives a cause of reproach. For widows who have children are not permitted under any circumstances to burn themselves with the bodies of their husbands...It is ordained they shall live to watch over the education of their children.

"A woman can not burn herself without having received permission from the governor of the place where she dwells." In many cases the governor grants permission after receiving a bribe. "Those to whom the governors peremptorily refuse to grant permission to burn themselves pass the remainder of their lives in severe penance or charitable deeds. There are some who frequent the great highways either to boil water with vegetables, and give it as a drink to passer-bys or to keep a fire always ready to light pipes of those who smoke tobacco. There are others among them who vow to eat nothing but what they find undigested in the droppings of oxen, cows and buffalo, and do still more absurd things."

“Immediately on permission being obtained, all kinds of music are heard...All the relatives and friends of the widow who desires to die after her husband congratulate her beforehand on the good fortune which she is about to acquire in the other world, and the glory which all members of the caste derive for her noble resolution...She dresses herself as for her wedding day, and is conducted in triumph to the place where she is to be burned. A great noise is made with instruments of music and the voices of women...The Brahmans accompanying her exhort her to show resolution and courage, and many Europeans believe...she is given some kind of drink that takes away her senses and removes all apprehension.”

Sati in the 1650

Describing a sati in Gujarat, Tavernier wrote: "On the margin of a river or tank, a kind of small hut, about twelve feet square, is built of reeds and all kinds of faggots, with which some pots of oil and other drugs are placed in order to make them burn quickly. The woman is seated in a half-reclined position in the middle of the hut, her head reposed on a kind of pillow of wood, and she rests her back against a post, to which she is tied by her waist." [Source: “Eyewitness to History”, edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

"In this position she holds the dead body of her husband on her knees, chewing betel all the time; and after about half an hour in this position...she calls out to the priests to apply the fire; this the Brahmans, and the relatives and friends of the woman who are present immediately do, throwing into the fire some pots of oil, so that the woman may suffer less by being quickly consumed. After the bodies have been reduced to ashes, the Brahmans take whatever is found in the way of melted gold, silver, tin, or copper, derived from the bracelets, ear-rings, and rings, which the woman had on."

Describing Suttee along the coast of Coromandel, Tavernier wrote: "A large hole of nine or ten feet deep, and twenty-five or thirty feet square, is dug, into which plenty of wood is thrown, with many drugs to make it burn quickly. When the hole is well heated, the body of the husband is placed on the edge, and then his wife comes dancing, and chewing betel, accompanied by all her relatives and friends, and with the sound of drums and cymbals."

"The woman then makes three turns around the hole, and at each time she embraces all her relatives and friends. When she completes the third turn the Brahmans throw the body of the deceased into the fire, and the woman, with her back turned towards the hole, is pushed by the Brahmans, and falls in backwards. Then all the relatives throw in pots of oil...so that bodies may be the sooner consumed."

Sati in Bengal

Describing sati in Bengal, Tavernier wrote: "A woman...come[s] with the body of her husband to the bank of the Ganges to wash in after he is dead, and to bath herself before being burned. I have seen them come to the Ganges after more than twenty days' journey, the bodies being by that time altogether putrid, and emitting an unbearable odor...In all Bengal, there is little fuel...poor women beg for wood out of charity to burn themselves with the dead bodies of their husbands." [Source: “Eyewitness to History”, edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

“A funeral pile is prepared for them, which is like a bed, with its pillow of small wood and reeds, in which pots of oil and other drugs are placed in order to consume the body quickly. The woman who intended to burn herself, preceded by drums, flutes and hutboys, and adorned with her most beautiful jewels, comes dancing to funeral pile, and ascending it she places herself, half-lying , half-seated."

"Then the body of her husband is laid across her, and all the relatives and friends bring her...[various things and]...she places [them] between her lap and the back of the body of her dead husband, calling upon the priest to apply fire to the funeral pile. This the Brahmans and the relatives do simultaneously...as soon as the miserable women are dead and half burned, their bodies are thrown into the Ganges with those of their husbands, where they are eaten by crocodiles."

sati, Hindu widow burning herself

Sati in the 1980s and 90s

On September 4, 1987, in the prosperous village of Deorala in Rajasthan, an 18-year-old Rajput newlywed named Roop Kanwar climbed on the funeral pyre of her husband, a 24-year-old college student who had died suddenly from a ruptured appendix. Some five thousand people from her village looked on as she burned to death.

Kanwar died with her husband' head on her lap. She wore the same crimson-and-gold sari she wore on her wedding day and led a procession to the pyre. She circled the pyre three times. It is not known whether she was pushed on or voluntarily mounted the fire. Onlookers said she sat crossed-legged with her hands folded and had a serene expression on her face. As she died the crowd cried, "”Sati”! “Sati”!" In the weeks that followed a half million pilgrims (including two members of Congress) visited the site, prayed and left offerings. Kanwar was regarded by many as a god and a monument was erected on the mound where she died.

In 1996, 39 villagers, including Kanwar’s father-in-law were acquitted of charges of abetting her suicide. Not one of the people who witnessed the suicide was willing testify, but they did restore the shrine in her honor and earned $150,000 in offerings and sales of a poster depicting Kanwar with her husband's head on her lap as the flames engulfed her. According to testimonies received by citizen's groups Kanwar did not climb on the funeral pyre willingly. They say she was coerced onto the pyre and was doused with flammable purified butter when she tried to get off. The whole incident caused such an uproar that Parliament enacted a new law that made the failure to stop a sati a crime. As of the late 1990s a police officer was posted at the site full time to prevent people from worshiping there.

In the late 1990s, in the village of Stpura (190 miles east New Delhi), a 55-year-old widow named Charan Shah climbed on her husband’s funeral pyre, touched her forehead on the fiery embers, and was burned to death. Villagers called it a sati. Police called it suicide and guarded the site where it happened to keep people from worshiping there and erecting a temple in her honor. Charan’s death was not conducted with the elaborate rituals that accompany a sati. She did not wear a wedding dress or go through the prescribed rituals. One witness told AP, "She was sitting still, as if in meditation. Charan Shah will one day be worshiped under temple."

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated June 2015