OPIUM IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA AND EGYPT

Minoan goddess of poppies

Opium comes from a poppy. There are numerous species of poppies, including the corn poppy, the Oriental poppy and the California poppy (California's state flower), but only two varieties of poppies "Papaver somniferum" and "Papaver bractatum") contain extractable amounts of opium and only the flower Papaver somniferum is used in the legal and illegal opium trade. The plant with flower is believed to be native to the Mediterranean area, [Sources for This Article: “Opium Throughout History”, The Opium Kings, Frontline, 1998, Erowid, Buzzed and National Geographic articles]

Opium is believed to have first been used in the Mediterranean because that is where opium originally came from.. The oldest known opium cultivators were people who lived around a Swiss lake in the forth millennium B.C. Traces of opium have been excavated from archeological sites there.

The first written record of opium use comes from a 5,400-year-old Sumerian description of the cultivation of a “joy plant” (Hul Gil) in lower Mesopotamia. The Sumerians passed on their knowledge of opium to the the Assyrians, who in turn passed it to the Babylonians. Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian texts refer to the medicinal uses of opium. A 9th century B.C. bas-relic from the Assyrian city of Nimrud shows King Ashymasirpal II holding a bouquet of opium capsules. The Babylonians are presumed to have introduced opium to the Egyptians.

The ancient Egyptians cultivated opium poppies sat least by1300 B.C. The capital city of Thebe was famous for its opium thebaicum poppy fields. The Egyptians took opium for pleasure and as a sedative. Hieroglyphics describe the cultivation of opium poppies during the reigns of Thutmose IV, Akhenaton and King Tutankhamen; the use of poppy extract to quiet crying children; and detail the opium trade across the Mediterranean between Egypt, Greece and Europe with Phoenicians and Minoans.

Ancient people are believed to be have taken opium, mostly in the form of tea or dissolved in other drinks. Opium-capsule-shaped ceramic jugs, dated to 1,500 B.C., have been unearthed in Cyprus. They featured stylized incisions and are believed to have held opium dissolved in wine. Surgical-quality knives were used to harvest opium have also been found in Cyprus. By 1100 B.C. "Peoples of the Sea" on Cyprus crafted surgical-quality culling knives to harvest opium, which they cultivate, trade and smoke before the fall of Troy. Ivory pipes, over 3,200 years old, were found in a Cyprus temple. They may have been used for smoking opium. Opium smoking pipes dated to 1000 B.C. to 300 B.C. have been recovered from archeological sites in Asia, Europe and Egypt.

See Separate Article OPIODS: TYPES, EFFECTS AND DANGERS factsanddetails.com HISTORY OF HEROIN factsanddetails.com ; OPIUM CULTIVATION AND HEROIN PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

3,500-Year-Old Opium Found in Ancient Israeli Grave

In September 2022, scientists from Israel say they have found evidence that the Canaanites used opium as an offering for the dead, as far back a 14th century B.C. Reuters reported: Opium traces have been discovered in Israel in vessels used in burial rituals by the ancient Canaanites, providing one of the world's earliest evidences of use of the drug. Discovered in a 2012 excavation in Tel Yehud in central Israel, the Late Bronze Age vessels, shaped like upside-down poppy flowers, were found at Canaanite graves, where they were likely used in burial ceremonies and for offerings for the dead in the afterlife, researchers said. [Source: [Source: Reuters, September 20, 2022]

A new joint study by the Weizmann Institute of Science, Tel Aviv University and the Israel Antiquities Authority, analysed organic residue in eight of the vessels and found that it was opium, some of which was produced locally and some in Cyprus. The findings date back to the 14th century B.C., the researchers said in their study, published in the Archaeometry journal. Precisely how opium was used by the Canaanites in their burial rituals, remains unknown, the researchers said. "It may be that during these ceremonies, conducted by family members or by a priest on their behalf, participants attempted to raise the spirits of their dead relatives in order to express a request, and would enter an ecstatic state by using opium," said Ron Beeri of the Israel Antiquities Authority. "Alternatively, it is possible that the opium, which was placed next to the body, was intended to help the person’s spirit rise from the grave in preparation for the meeting with their relatives in the next life," Beeri said.

According to Live Science: Archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Weizmann Institute of Science found the opium-laced pottery, alongside the skeletal remains of a male who died between 40 and 50 years of age, in 2017, according to a study published July 2, 2022 in the journal Archaeometry. "There was a hypothesis in 2017 that because some of the jugs resembled poppies, that they might contain opium," Vanessa Linares, a doctoral candidate at Tel Aviv University and the study's lead author, told Live Science. "We found that was the case and that opium was contained inside some of the vessels."

While it's not clear why opium was part of this particular burial, Linares said researchers have several theories based on historical documentation from other ancient civilizations around the world. "According to the historical and written record, we see that Sumerian priests used opium to reach a higher state of spirituality, while the Egyptians reserved opium for warriors as well as priests, possibly using it not only to have a psychoactive effect but also for medicinal processes, since its main compound is morphine, which is used to help with pain," Linares said. "Perhaps it was also there as an offering for the gods, and maybe they thought that the deceased would need it in the afterlife," she added. "I think we can make a lot of speculations and suggestions for why it was there." [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, September 24, 2022]

Earliest Evidence of the Opium Trade — from Cyprus

The oldest chemical evidence for the ancient drug trade comes from traces of opium found in Cyprus. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Scientists based at the University of York and the British Museum analyzed the residue found inside a small late Bronze Age jug from Cyprus and discovered the presence of opium alkaloids. The “base-ringed juglet” owned by the British Museum had long been assumed to be connected to the opium trade because the head of the jug, like other similar examples from the region, resembles the poppy flower. This was very much a “best-guess,” however, and it was not until Professor Jane Thomas-Oates of the University of York was able to analyze the contents of the jug that the suspicion was confirmed. The discovery offers evidence that there was a flourishing trade in opium in the Eastern Mediterranean as long as 3,600 years ago. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 6, 2018]

This doesn’t mean, however, that the opiate jug was used to transport and preserve narcotics. The presence of oil residue in the jug suggests that, rather than containing pure opium, the jug held poppy seed oil or aromatic oils used for perfume or body oil. Even so, there are numerous literary and artistic sources that confirm that opium was known to ancient physicians.

What’s surprising about the recent discovery in the UK is that it demonstrates and confirms the existence of an ancient form of branding. Not only did these distinctive looking juglets contain poppy-based products, but the containers were deliberately fashioned in order to communicate their purpose. Whether or not the oils contained therein served an analgesic purpose, they are one of the earliest forms of pharmaceutical marketing.

Opium in the Greco-Roman Era

Opium poppies in ancient Egypt

In Greco-Roman times, opium was used in religious rituals, as an ingredient in magic potions and as a painkiller, sedative and sleeping medicine. The potion "to quiet all pain and strife and bring forgetfulness to every ill" taken by Helen of Troy in Homer's “Odyssey” is believed to have contained opium. Some scholars have suggested that the "vinegar mingled with gall" offered to Christ on the cross contained opium because the Hebrew word for gall (“rôsh” ) means opium. Homer and Virgil wrote about opium. Poppies were pictured on Greek coins, pottery and jewelry, and on Roman statues and tombs (where poppies symbolized a release from a lifetime of pain). The Greek scholar Theophrastus (371-287 B.C.) wrote about the use of opium poppy juice and mentioned opium in connection with myths of Ceres and Demeter. Alexander the Great introduced the drug to India and Persia in 330 B.C.

By 300 B.C., opium was used by Arabs, Greeks, and Romans as a sedative and soporific. The founding fathers of medicine, Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscorides, all wrote about opium. Hippocrates dismissed the magical attributes of opium but acknowledged its usefulness as a narcotic, a styptic (a substance that can stop bleeding when is applied to a wound) and a treatment for internal diseases, female ailments and epidemics. In the A.D. second century, Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius took opium to sleep and deal with the stress of prolonged military campaigns. The Romans reportedly used toxic doses of opium to poison their enemies.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: A number of ancient Greek gods associated with sleep — most prominently, Hypnos (Sleep) and Nyx (Night) — are portrayed adorned with poppies. The use of poppies as a kind of sleeping aid is found in mythological stories. According to legend, when Persephone was abducted and taken to the underworld, her grief-struck mother Demeter consumed poppies in an effort to sleep. The poppy became one of her emblems and appears on ancient coins from the Cyclades. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 6, 2018]

See Separate Article: RECREATIONAL DRUGS IN ANCIENT GREECE AND ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Opium Use

Akha tribesman with opium pipe in the Golden Triangle Opium can be dried into a black, gooey, ball (gum opium) or pounded into a powder (opium powder). It can also be made into alcohol-water extract and called tincture of opium ( known as laudanum in the 19th century). The pods can be steeped in water to produce a bitter tea that has a mild, long-lasting high.

In some parts of the world, it is perfectly acceptable for old people to smoke opium. The drug is regarded as a kind of reward for a lifetime of hard work and a form of relief from the aches and pains of old age. What is frowned upon is young people who waste away their productive years smoking the drug and not working.

Particularly in the Golden Triangle of Southeast Asia, opium is consumed on casual, temporary basis by backpackers and other travelers. On drug traveler in Laos, who was still suffering after smoking opium the night before, told AP, "It wasn't what I expected. I thought it was going to be a much out-of-body sort of thing. I just felt like laying there and thinking. Any time I moved around, I thought I would get sick."

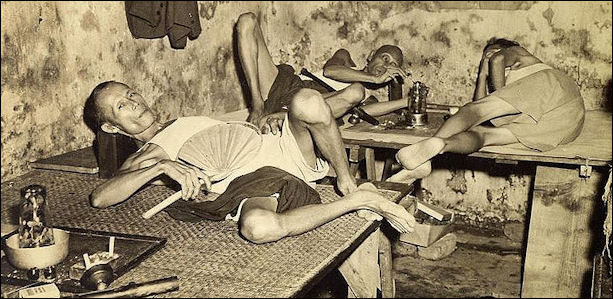

Opium Smoking

The smoking of opium does not involve burning as is the case with cannabis or tobacco. Rather prepared opium is indirectly heated to temperatures that cause the active alkaloids, chiefly morphine, to vaporize. Opium users in much of the world have traditionally “smoked” the drug in a specially-designed pipe with a long bamboo stem and a glass, porcelain or metal bowl. They usually have taken the drug while laying on their side because the nature of the high discourages people from standing up or even sitting down. Those that try to sit up often just slump over.

To prepare the tar-like opium for consumption it is first heated and softened and rolled into a pea-size ball, enough for a single dose for one individual. Users seem take great pleasure going through the preparation process. The ball is then stuck on the bowl and heated indirectly by heating the bowl not than opium itself with a candle or lamp. Sometime users blows through the pipe to heat a piece of glowing charcoal to increases the heat. When the opium begins to vaporize the smoker inhales.

Opium in India Often it takes two people to smoke opium: one person to smoke it and another person to heat the opium ball with a flame and make sure it releases the drug without being sucked into the pipe. Pipes were often designed with a rounded cross section that allowed the bowl to be rotated into the heat source and rotated back into an upright position. Chasing the dragon works with opium. In a conventional marijuana pipe opium often slides down the bowl before it fully vaporizes.

While it is being inhaled, opium gurgles, fizzes and hisses and slithers down the pipe like black mercury. Opium balls are smoked slowly and carefully lit and nurtured so they aren't sucked quickly into the pipe. The heated vapor is easily absorbed by the body. When the ball is finished, the smoker relaxes and spaces out. He usually doesn't have much to say, doesn't want to do much except lay there, and is quite happy being left alone with his happy thoughts.

I smoked opium once with the Lisu hill tribe in Thailand. We walked about a three hour walk from the main road to get to the village where we smoked it. The village and people were quite shabby. We paid about 50 cents for each hit, which was prepared and heated by a villager. I had six pipefuls, ignoring advise to limit myself to three, and felt good and relaxed while laying down and smoking it but nauseous and dizzy when I stood up. During the three hour hike back to my guest house I felt sick and disoriented. As walked I told my friends not to talk to me because I couldn’t concentration on too many things at once. Afterwards I had no real compulsion to try opium again anytime soon.

Opium Heads East

Some scholars believe that opium was brought to China by returning sailors or Tibetan Buddhist priests from Africa or India as the early as the first century B.C. Others say that opium more likely were carried east by Arabic traders to India and then China between A.D. 400 and A.D. 900. As we said before Alexander the Great introduced the drug to India and Persia in 330 B.C. Opium thebaicum, from the Egyptian fields at Thebes, was s first introduced to China by Arab traders around A.D. 400.

By reign of Kublai Khan (1279-94) opium was widely used as a medicine. In India, it was eaten and drunk by all classes of people and taken as a household remedy for a variety of maladies. Between the 1000 and 1500 the Chinese graduated from consuming poppy seeds to taking raw opium from the capsules to refining high quality opium. In southern China hill tribes began raising opium as a way to pay taxes to the Han Chinese.

In the 1600s, residents of Persia and India began eating and drinking opium mixtures for recreational use. In the Indian Mogul Empire (1526-1857), war elephants and soldiers were given opium to give them courage, calm them before battles and make them feel less pain when injured. Emperor Shah Jahan, the builder of the Taj Mahal, drank opium with his wine and decorated the tomb of his beloved wife with poppies. Under the Moguls opium agriculture organized and the sale of opium became a state monopoly.

Until the practice of smoking tobacco was introduced to Europe and Asia from the Americas in the 16th century, opium was mostly eaten or drunk. Opium smoked in the 17th and 18th century was mostly in the form of a mixture of opium and tobacco called madak. Smoking pure opium only became popular in China after madak was banned there. By 1700, the use of tobacco-opium mixtures (madak) had begun in the East Indies (probably Java) and had spread to Formosa, Fukien and the South China coast. In 1689, Engelberg Kaempfer inspected primitive dens where the mixture is dispensed (Amoenitates Exoticae, 1712:642-5).

Opium Trade Between Asia and Europe

In the 1600s, Portugese merchants began carrying cargoes of Indian opium through Macao into China. In 1606, ships chartered by Elizabeth I were instructed to purchase high-quality Indian opium and transport it back to England. In 1700, the Dutch export Indian opium to China and the islands of Southeast Asia; the Dutch introduce the practice of smoking opium in a tobacco pipe to the Chinese.

In 1750, the British East India Company took control of Bengal and Bihar, the opium-growing districts of India, and British ships began dominating the opium trade out of Calcutta to China. By 1767, The British East India Company's import of opium to China reaches a staggering two thousand chests of opium per year.

In 1793, The British East India Company established a monopoly on the opium trade. All poppy growers in India were forbidden to sell opium to competitor trading companies. In 1800 The British Levant Company purchases nearly half of all of the opium coming out of Smyrna, Turkey strictly for importation to Europe and the United States.

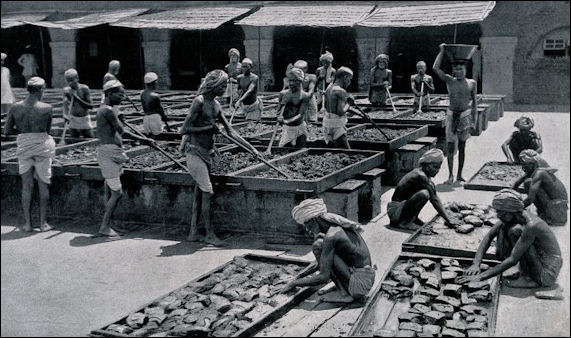

Manufacture of opium in India

Opium in China

Opium has long been used in China and the Far East to stop diarrhea and treat other medical problems. By 1000, the medicinal use of opium poppy seeds is widespread. By 1100, the more potent capsule is in use, but pure opium is not extracted from the capsule. By the medicinal use of pure opium is fully established; native opium is manufactured, but recreational use was still limited. In the 1600s, the habit of smoking opium became popular in Formosa (now Taiwan) after Dutch sailors introduced tobacco smoking and residents of the island mixed tobacco and opium. The Formosans introduced the custom to the mainland, where tobacco was abandoned and opium was smoked alone. [Source: Erowid.org]

The quality of the opium produced in China was inferior to the opium brought from India by the British. Opium from Bengal continues to enter China despite the edict of 1729 prohibiting smoking. It increased in frequency from 200 chests annually in 1729 to 1000 annually by 1767. Much of it was for medicinal use. Tariffs were collected on the opium.In 1757, when Britain annexed Bengal, the Chinese confined foreign trade to Canton where it could be restricted and controlled in the interests of revenue for the Chinese. Hong Kong merchants serve as intermediaries between the foreigners and the Chinese authorities.

1799, Chinese Emperor Jiaqing (1760-1820) banned opium completely, making trade and poppy cultivation illegal. A strong edict by authorities at Canton, supporting the emperor's decree of 1796, forbid opium trade at that port. A concurrent drive against native poppy growing was initiated. Opium became an illicit commodity. The British-supplied opium was very popular in China. Rich and poor Chinese alike gathered in opium dens called divans to smoke the dreamy drug, and millions of Chinese — government officials, merchants, court servants, sedan bearers — became addicted and subdued. The opium trade significantly ate into the China's foreign trade reserves. By 1836, it transformed a huge trade surplus into huge trade deficit, setting the stage for the Opium Wars.

In 1839, Lin Tse-Hsu, the imperial Chinese commissioner in charge of suppressing the opium traffic in China, ordered all foreign traders to surrender their opium. In response, the British sent a group of warships to the coast of China, triggering the First Opium War, which the British won in 1841. Along with paying a large indemnity, the defeated Chinese ceded Hong Kong to the British. In 1856, hostilities towards China were renewed, this time by the British and French, resulting in the Second Opium War, which China again lost. After this China was forced to pay more indemnity and the importation of opium to China was legalized.

After the Opium Wars, the British aggressively marketed opium in China. The result: lots of addicts. Some smoked the drug in opium dens. Others took opium pills. Cheap pills known as pen yen gave rise to the expression have a "yen" for something. In 1900-1906, it was estimated that 27 percent of the adult male population of China was addicted to opium. This was about 3.5 percent of the total population of the country. It wasn’t until 1906 that Britain and China enacted a treaty restricting the Sino-Indian opium trade. In 1910, after 150 years of trying, China was finally successful in convincing the British to dismantle the India-China opium trade. By that time China had plenty of other sources for the drug, particularly in Southeast Asia.

See Separate Articles OPIUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; OPIUM WARS PERIOD factsanddetails.com/china ; OPIUM WARS AND THEIR LEGACY factsanddetails.com

opium in Old Calcutta Chinatown

Early Medical Uses of Opium in Europe

In the 1300s, opium disappeared from European historical record due to the Holy Inquisition. "In the eyes of the Inquisition, anything from the East was linked to the Devil." In 1527, opium was reintroduced into European medical literature by Paracelsus in form of "laudanum" (See Below) In the 15th and 16th century "syrup of poppy" and other poppy preparations were commonly prepared and used medicinally by monastic communities that devoted major efforts to the production and improvement of herbal medicines. In the 17th Century, hashish, alcohol, and opium use spread to Europe from Constantinople. [Source: Erowid.org]

The pioneering physician Paracelsus is credited with invented tincture of opium (opium dissolved in alcohol, later called laudanum) in 1530. Black laudanum pills — "Stones of Immortality" — were made of opium thebaicum, citrus juice and quintessence of gold and prescribed as painkillers. Describing its good and bad points, one 16th-century botanist wrote "it mitigateth all kinds of paines, but it leaveth behinde oftentimes a mischiefe woorse than the disease itselfe." Opium is believed to be the “drowsy syrup” in Shakespeare’s Othello.

In 1680 the English apothecary, Thomas Sydenham, introduces Sydenham's Laudanum, a mixture of sherry wine, opium and herbs. His pills along with those of others were used to treat a wide range of ailments. In 1753, Linnaeus, the father of plant and animal classification, first classified the opium poppy as Papaver somniferum — ''sleep-inducing'' — in his book Genera Plantarum.

Opium production began to take off as opium cultivation improved. In 1794, a Briton named Thomas Jine received a gold medal and 50 guineas for being the first person to produce 20 pounds of opium on a 5 acre plot of land. Twenty years later, a Scottish surgeon named John Young produced 56 pounds of opium on one acre along with potatoes, used to protect the fragile young opium plants from severe weather.

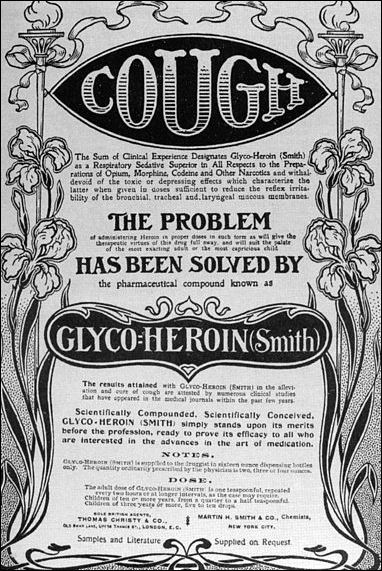

In the 1800s, patent medicines and opium preparations such as Dover's Powder were readily available without restrictions. Laudanum tincture was cheaper than beer or wine and could easily be purchased by even poorly-paid work As a result, throughout the first half of the 19th century, the incidence of opium dependence appears to have increased steadily in England and Europe.Working-class medicinal use of opium-bearing nostrums and sedatives for children were common in England.

Between 1800 and 1820, domestic opium cultivation encouraged increased opium use. Rising prices and problems with adulteration may have played a part in declines after the 1820s. There does not appear to have been any efforts to control it use at that time.

Opium in the United States

In 1800 when the British Levant Company purchased nearly half of all of the opium coming out of Smyrna, Turkey importation of opium to the United States increased. In 1805, a smuggler from Boston, Massachusetts named Charles Cabot, attempted to purchase opium from the British, then smuggle it into China under the auspices of British smugglers. In 1812, American John Cushing, under the employ of his uncles' business, James and Thomas H. Perkins Company of Boston, became a rich man by smuggling Turkish opium into Canton. In 1816 John Jacob Astor of New York City of the American Fur Company, smuggled ten tons of Turkish opium into Canton. By 1840, New Englanders brought 24,000 pounds of opium into the United States. U.S. Customs took notice and put a hefty duty fee on the drug’s import.

Opium and cocaine were introduced to the United States in the 19th century in part as cures for alcoholism. Opium use in the United States took off in the 1840s on the heels of a temperance movement lead by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League that caused drinking in the U.S. to decline by half to three quarters. An 1872 report issued by the Massachusetts State Board of Health noted that “between 1840 and 1850, soon after teetotalism had become a fixed fact...our own importation of opium swelled.”

.jpg)

Opium Seller by W. Muller In the 19th century, opium was so cheap in United States, it became a favorite medicine among working people as it did in Europe. Laudanum (meaning “to be praised”) and "home remedy" tonics such as Hooper's Anodyne, were widely prescribed for a number of illness, especially diarrhea, well into the 1930s. Godfrey's Cordial was given to babies to quiet them. Mrs. Winslow’s soothing syrup was recommended for young children who were teething. Other opium products were touted as a cures for alcoholism and marketed to wives to as way to control their alcoholic husbands.

Between 1850 and 1865. Tens of thousands of Chinese laborers migrate to the U.S. during a labor shortage there, bringing the habit of opium smoking with them. Opium dens opened in San Francisco and towns where Chinese railroad workers stayed. By 1890, there were a number of "smoke houses" in the basements in back-ally buildings in New York. The customers included prostitutes, showgirls, businessmen and tourists as well as Chinamen. Opium became widely associated with dark, smoky opium dens. The custom made its way to Europe from China via the United States.

In 1878, San Francisco passed an ordinance making it a misdemeanor to "keep, or maintain, or visit, or in any way contribute to the support of any place, house, or room, where opium is smoked." Importation, sales and possession of opium remained legal. In San Francisco, smoking opium in the city limits was banned but was allowed in neighboring Chinatowns and their opium dens. In 1887, the importation of opium by Chinese — but not by Americans — was outlawed. After that tabloids owned by William Randolph Hearst publish stories of white women being seduced by Chinese men in opium dens. This was an effort to drum up 'Yellow Peril' fears disguised as an "anti-drug" campaign.

Opium, Addiction and European Intellectuals in the 19th Century

Opium was popular among British and French intellectuals in the 18th and 19th century. Balzac, Shelly, Byron, Dickens, and the artist Gauguin were all enthusiastic opium users. Long before them you could find reference to the drug in Chaucer, Milton and Shakespeare.Samuel Taylor Cooleridge wrote “Kublai Khan” , seen by some as an ode to opium, while high on laudanum. In 1819, the writer John Keats began experimenting with opium strictly recreational use. He and his intellectual friends took the drug simply to get high and took it at extended intervals so they wouldn’t get addicted. Elizabeth Barrett Browning became addicted to morphine in 1837. This, however, did not interfere with her ability to write "poetical paragraphs."

In the early 19th century, England was “marinated in opium, which was taken for everything from upset stomachs to sore heads,” according to Frances Wilson, author of “Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey”. A New Yorker review of te book said: It was swallowed in the form of pills or dissolved in alcohol to make laudanum. The Turks, it was said, all suffered from opium dependence. But English doctors prescribed it with abandon. The drug was given to women for menstrual discomfort and to children for the hiccups. All the while, its glamour was growing: it was ancient, shamanic, a supernatural tether to otherworldly visions. [Source: Dan Chiasson, The New Yorker, October 17, 2016]

An awareness endemic opium use grew in Flemish areas of Europe in the the mid 19th-century. While some people could tolerate and successfully control their use by informal social mechanisms others could not. Use was particularly widespread among poorer classes, agricultural communities inhabitants of small hamlets and isolated farms, and women and babies. Contemporary observers said many people started using to treat rheumatic pains but after a while it became a plague everywhere in Flanders. In 1839, opium and its preparations were responsible for more premature deaths than any other chemical agent in Britain. Opiates account for 186 of 543 poisonings, including no fewer than 72 among children. [Source: Erowid.org]

Thomas De Quincey: the English Opium-Eater

In 1821, Thomas De Quincey published his autobiographical account of opium addiction, 'Confessions of an English Opium-Eater.' He was 36 when the sensational memoir was published, anonymously. A few years before that he befriended the poet William Wordsworth and helped him take care of his children. De Quincey started using opium after the death of the poet’s daughter Catherine Wordsworth, of “convulsions” at the age of three. De Quincey slept on the girl’s grave for more than two months, and witnessed her apparition walking the nearby fields. The grief gave him stomach pain for which he“yielded to no remedies but opium.” Laudanum, the tincture of opium, was his preferred form of the drug, which we can assume he drank rather than are. [Source: Dan Chiasson, The New Yorker, October 17, 2016]

Dan Chiasson wrote in The New Yorker: “De Quincey had seen as a warning the escalating addiction of Coleridge, who, for his part, recognized in De Quincey a doppelgänger, their “two faces, each of a confused countenance,” blended with the same mixture of “muddiness and lustre.” But De Quincey’s opium use now passed the point of no return, peaking at a rate of approximately four hundred and eighty grains per day, or twelve thousand drops of laudanum. The next several years of his life, though they coincided with” his marriage and the birth of his first child “can be understood only in terms of the dark visions and anxieties that dogged him constantly. Coleridge had his “person from Porlock,” whose knock at the door of his cottage both interrupted and made possible the composition of “Kubla Khan.” For De Quincey, his anxiety about the birth of his child was linked to the sudden appearance of a mysterious Malay in “turban and loose trousers of dingy white,” who turned up on the doorstep and, having ingested a large share of De Quincey’s opium, bolted and was never seen again.

De Quincey’s writing career began with a series of failures that nevertheless opened to him his true subject. A longtime conservative, he got a lucky break when asked, in 1818, to take over as editor of a local Tory newspaper, the Westmorland Gazette. Under his editorship, the quiet family paper started running columns about opium trips, opinions about Kant, and salacious tabloid items about murders across Europe. De Quincey resigned after eighteen months, but during his tenure he introduced the use of imaginative fantasias to frame his own travails as a subject worthy of the public eye. His pieces were often marked by accounts of the dramas he suffered while trying to write them, the odd personal intercalations reliant upon the expectation that he would write straight journalism. The formula had been set early: debt, here in the form of deadlines unmet; procrastination; and opium. But now there was a new addition to the sequence: writing.

In his essay “Coleridge and Opium-Eating,” De Quincey wrote that he had found opium referenced, in John Milton’s great Biblical epic: “You know the Paradise Lost? and you remember from the eleventh book, in its earlier part, that laudanum already existed in Eden — nay, that it was used medicinally by an archangel; for, after Michael had “purged with euphrasy and rue” the eyes of Adam, lest he should be unequal to the mere sight of the great visions about to unfold their draperies before him, next he fortifies his fleshly spirits against the affliction of these visions, of which visions the first was death. And how? “He from the well of life three drops instill’d.”

“The image of Adam getting high in the Garden of Eden may seem outlandish, but opium had made a kind of Adam out of De Quincey: in “the bosom of darkness, out of the fantastic imagery of the brain,” he wandered through ancient cities “beyond the splendour of Babylon and Hekatómpylos,” crammed with “temples, beyond the art of Phidias and Praxiteles.” Opium deepened his “natural inclination for a solitary life” by giving a cosmic cast to idleness. “More than once,” he wrote, “it has happened to me, on a summer-night, when I have been at an open window . . . from sun-set to sun-rise, motionless, without wishing to move.”

“Confessions of an English Opium-Eater”

In the book De Quincey described how "subtle and mighty opium" brought him music like perfume and a hundred years of pleasure in one night but then went on to compare his addiction to the drug with cancerous kisses from crocodiles and a thousands of years in stone coffins." Quincey wrote, "Farewell to smiles and laughter, farewell to peace of mind! Farewell to hope and to tranquil dreams, and the blessed consolations of sleep!"

Dan Chiasson wrote in The New Yorker: “When the “Confessions” was first published, in The London Magazine, it appeared in two installments; the second included sections on the “Pleasures of Opium” and the “Pains of Opium.” There were familiar disputes about whether De Quincey was corrupting the young, but the main intoxicant on display was his prose, which derived its power from being written in the grip of its subject. De Quincey beheld, in the “theatre” of his mind, along with “more than earthly splendours,” horrors beyond belief: “vast processions” of “mournful pomp,” and “friezes of never-ending stories” as terrifying as Greek tragedies. Space “swelled” around him; time hemorrhaged so that he seemed “to have lived for 70 or 100 years in one night.” He especially dreaded a recurring vision of the ocean “paved with innumerable faces, upturned to the heavens: faces, imploring, wrathful, despairing, surged upwards by thousands, by myriads, by generations, by centuries.” [Source: Dan Chiasson, The New Yorker, October 17, 2016]

De Quincey experienced subjective impressions as though they were real and wrote about them as though their reality could be conveyed, in all its Technicolor wonder and horror. He witnessed with his senses what some of his contemporaries only pondered in the abstract; opium levelled, for him, the distinction between actual and imagined things. “I seemed every night to descend, not metaphorically, but literally to descend, into chasms and sunless abysses, depths below depths,” he wrote. When the writer Maria Edgeworth read Milton’s lines about Hell (“And in the lowest deep a lower deep / Still threatening to devour me opens wide”), she objected: How could the lowest deep open into a lower deep? De Quincey answered, “In carpentry it is clear to my mind that it could not.” But in cases of “deep imaginative feeling” it was natural to behold the “never-ending growth of one colossal grandeur chasing and surmounting another, or of abysses that swallowed up abysses.”

He wrote in defiance of chronology, which he called a “hackneyed roll-call.” In his visions, events widely separated in time were yoked together by the imagination — which, in turn, because of his delusions, was his reality. “Our deepest thoughts and feelings,” he wrote, “pass to us” through “compound experiences” that dissolve the gap between one end of the time line and the other. The details of his life were like carrousel horses, disappearing around the bend and reappearing, in his visions as in his writing, with fresh intensity and vividness.

Book:“Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey” by Frances Wilson, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2016]

Invention of Morphine

Morphine, heroin and cocaine were all invented or brought to the market by German chemists. Morphine was first derived from opium poppies by a 20-year-old pharmacist assistant name Friedrich Sertuerner of Paderborn, Germany in 1803. He named the drug “morphium “ after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams, and ran experiments on himself, describing the curative, euphoric and "terrible" aspects of the drug.

Sertuerner discovered the active ingredient of opium by dissolving it in acid then neutralizing it with ammonia, producing the alkaloid — Principium somniferum, or morphine. He received prizes, cash and international recognition for his discovery but morphine did not become widely used until the invention of the hypodermic needle . Morphine is believed to have been the first alkaloid to be isolated from a plant, The discovery set off a flurry of research into plant alkaloids which in turn led to the isolation of atrophine, caffeine, cocaine, quinine and other important drugs. Within half a century all these were made into medicines prescribed with precisely measured dosages for the first time.

E. Merck & Company of Darmstadt, Germany began commercially manufacturing morphine In 1827.Morphine and opium were used before anesthesia was invented to relieve the pain of surgery. Wounded soldiers were given morphine poured onto gloves, which they licked periodically to relieve their pain. U.S. army medical kits still contain morphine, which is considered so important it remains part of the U.S. Strategic and Critical Materials Stockpile.

Image Sources: 1) DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration); 2) Normal Museum; 3) Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Buzzed, the Straight Facts About the Most Used and Abused Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy” by Cynthia Kuhn, Ph.D., Scott Swartzwelder Ph.D., Wilkie Wilson Ph.D., Duke University Medical Center (W.W. Norton, New York, 2003); 2) National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 3) United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and 4) National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, The Independent, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, , Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2024