LIANAS

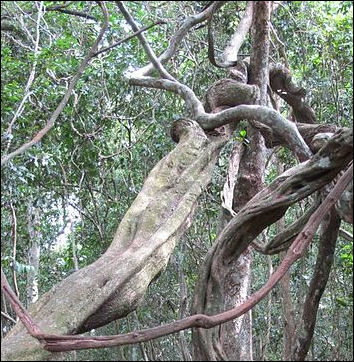

Lianas The rainforest is filled with thick, woody vines known as lianas, or climbers. Found in almost every tropical location these plants sprout up at ground level, send out shoots which clasp on to trees and vegetation, and then climb their way up to the canopy, where often they sometimes link trees together and become as large as trees themselves. A number of families of flowering plants are described as lianas. There are also climbing ferns, climbing bamboos, and climbing gymnosperms (relatives of conifers). [Source “Rainforest Canopy, the High Frontier” by Edward O. Wilson, National Geographic, December 1991]

Lianas are elastic, hard to break and rope-like and able to support the weight of humans. The islanders on Vanuatu that inspired bungee jumping leapt from platforms using them. Monkeys and orangutans hand from them. Still, it is difficult to swing on them from to tree to tree Tarzan-style since they are ultimately attached to the ground. Lianas do have other uses though. If you run out water in the rainforest try cutting open a liana. Some produce a stream of water that is enough to fill several canteens. Pygmies, Amazon Indians and Borneo Aboriginals all collect water from lianas on hunting expeditions. [Source “Tropical Rainforests: Nature's Dwindling Treasures”, by Peter T. White, National Geographic, January 1983]

About half of all canopy trees have lianas. To make their way up trees, lianas are equipped with claws, hooks, glues, suckers, corkscrews and Velcrolike bristles. Some work their way straight up the tree by clinging to the bark. Others loop around branches, moving from limb to limb, and make their way up like charmed snakes. These kinds of lianas usually can't bridge a gap of more than five feet, and they need at least some sunlight to survive. If they fail to find something to support them they eventually collapse under their own weight. [Source: Mark Moffett, Smithsonian]

Websites and Resources: Rainforest Action Network ran.org ; Rainforest Foundation rainforestfoundation.org ; World Rainforest Movement wrm.org.uy ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Forest Peoples Programme forestpeoples.org ; Rainforest Alliance rainforest-alliance.org ; Nature Conservancy nature.org/rainforests ; National Geographic environment.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rainforest-profile ; Rainforest Photos rain-tree.com ; Rainforest Animals: Rainforest Animals rainforestanimals.net ; Mongabay.com mongabay.com ; Plants plants.usda.gov

Books: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); “Portraits of the Rainforest” by Adrian Forsythe.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

BIODIVERSITY AND THE NUMBER OF SPECIES factsanddetails.com ;

AMAZON: RIVER, FOREST, HISTORY, ECOLOGY factsanddetails.com ;

TREES: OLDEST, TALLEST, UNUSUAL SPECIES, COMMUNICATION factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST TREES, FRUITS, PLANTS AND BAMBOO factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST ORCHIDS AND FLOWERS factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

STUDYING THE RAINFOREST: METHODS, TECHNOLOGIES AND HARD WORK factsanddetails.com

Liana Growth

lianas Lianas begin their life as small self-supporting plants like other plants. Some species can reach a height of six feet without grabbing on to anything. When a liana does find a supporting tree, known to scientists as a trellis, it begins to grow very rapidly. As it grows the stem become thicker and rectangular and the material properties of the stem changes radically. The wood of a self-supporting liana is stiff and dense like woods of many trees. When the liana changes into a vine the vessels of the wood that conduct water becomes larger and the amount of cellulose shrinks. The stem absorbs more water and becomes as much as three times more elastic as other wood plants. The stems are especially soft and pliable at the end of the wet season when are full of water.

When a liana changes from a self-supporting liana into a vine, the fibers changes from a longitudinal orientation to a slanted orientation. Under this configuration the fibers can rearrange themselves as the wood stretches, with energy either dissipated as friction and heat or stored as potential energy. When a force, such as a hanging monkey, is applied to the vine the slanting structure allows the vine to stretch, in some cases becoming up to 30 percent longer and significantly thinner.

Freed from having a trunk and supporting their own weight, lianas can use more of their energy to roam canopy and gathering nutrients and sunlight. In some rainforest they account for half the leaf productivity but only 5 percent of the biomass. To move large amounts of water from the ground to the leaves, they have large tube-like vascular channels much larger than those in other plants (the channels in temperate plants are much smaller so the water in them doesn't freeze).

Kinds of Lianas

Some of the larger climbers, like the South American "monkey ladder," look like sheets of lasagna and wrap themselves around trees like rope. The seedlings of some species can make several loops around a small branch in a single day. Other species, like some members of the pea family, look like poles until the reach the canopy, where they branch out again and again and can end up covering dozens of trees and occupying more than an acre.

strangler fig One of the most unusual vines in the rainforest is the Central American cheese plant. Seedlings grow on the ground in groups like spokes of a wheel. Unlike most plants they seek shade. If they don't find a tree within six feet they die (the food supply in their seed gives out). If they find a tree they grow upwards and change their orientation and begin seeking sunlight. They then grow leaves and then produce their own food. As the vine climbs the leaves get bigger and bigger and develop holes like those in Swiss cheese, hence the name of the plant. . [Source: David Attenborough, The Private Life of Plants, Princeton University Press, 1995]

Strangler Figs

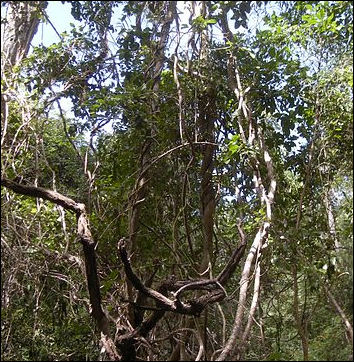

Tarzan is more likely to have swung from strangler figs which germinate in the canopy and send dangling roots to the forest floor to obtain groundwater and nutrients. If enough water and nutrients can be secured the leaves grow vigorously and the roots began to wrap around the trunks of trees. After a while the fig leaves crowd out the leaves of the host tree and the fig becomes stronger than its host.

There are hundreds of different kinds of strangler figs. They reason they developed the way they did was to get close to sunlight right from the start. The main drawback of this strategy is that their exposure to the elements makes the seedlings more vulnerable to dryness and insect attacks than if they grew on

Mature strangler figs often envelop and kill off their host trees. They don't strangle the trees, although it looks like it sometimes. Instead they restricts the tree's growth and prevents it from producing new vessels which the tree needs to transport nutrients from the soil to the canopy. Stranglers generally don't kill palms because they don't needed to expand their diameter to produce new vessels. Strangler figs also kill their hosts by blocking out the sun and depriving their leaves of the energy they need for photosynthesis..

When the host tree has rotted away the hollow lattice of fig roots resembles a trees itself. Many of these are actually two or three figs entangled together so they look like one plant. As many as eight individual strangler figs have been fund on a single host.

Strangler Figs, Wasps and Animals

strangler fig Some fig species are dependent on specific wasps species for pollination. The wasps use fig fruit as a safe place to lay their eggs. If a wasp species linked to a particular fig were ever to become extinct, so too would the fig. The symbiotic relationship between the fig and wasp works like this: A female wasp, carrying pollen from male flowers inside the fig where she was born, enters the fig through an entryway at the bottom of the fruit. She lays her eggs in fig's ovaries, spreading pollen from the male flowers as you goes. This allows the fig to reproduce. After she is finished she dies. Young wasp larvae emerge from the eggs and feed on the fruit's flesh and mate. Male wasps die inside the fruit and females, covered with pollen, emerge to begin the cycle again.

Many animals and birds eat the fruit produced by strangler figs. Unlike fruit trees such as mangos that produce all their fruit at once during one season, each species of strangler figs produce fruit year round. Although figs are not the favored food of most animals, they are commonly eaten because they are such a dependable food source. A number of species rely on figs for their survival.

Animals that eat figs help disperse the undigested seeds in their feces. Birds, bats, monkeys and other animals that live in the canopy eat figs off the tree. Many figs turn yellow when they are read to harvest to signal fruit-eating bats and other animals they are ready to eat. The yellow is easier for dark-seeing fruit bats to see. Wild pigs, civets and deer eat figs that have fallen to the ground. Sometimes small ants that carry the seeds away. Most of these seeds are consumed, but those that aren't have a good chance of germinating.

Most seeds fall to the ground, where fail to grow without sunlight. Some land in the decayed leaves and moss that collect in the clefts of tree branches. There they sometimes take root and grow before they are consumed by insects. Very, very few develop into mature plants.

Rattan

Rattans are climbing palms native to southeast Asian. The have tough and slender stems as thick as a man’s finger and tendrils with hooks sharp enough to rip a shirt or scrape skin. The hooks are used to attach to trees so the plants can climb upwards. In the forest they flourish as parasitic vines that cling to the forest with “multiple throned tentacles” hundreds of feet long.

Rattan palms yield a fiber called, obviously enough, rattan that is prized for making furniture, baskets, mats, brushes, hampers, and even canes. The strongest and most valuable part of the vine is the skin. The fibers are covered with spines which are used for climbing up the trunks of trees.

Once a rattan establish itself on a tree it can climb to the top of the canopy and sprout huge palm-leaves that can block out the sun on its host plants. Rattans continue to grow vigorously even if their weight overwhelms branches and brings the host plants crashing to the ground. They can grow to length of over 500 feet, giving them longer stems than any other plant, and thereby, by some standards, making them the world’s longest plants. .

Like other palms, rattans are nearly always unbranched and grow only from the bud at their end. If something happens to the bud, the plant can die. The crown is often very tasty and animals like to eat it. Their sharp spines for protection.

Rattan palms have some very complicated relationships with other forms of life. The tips of some species of rattan are protected by small black ants that produce a loud hissing noise by banging their heads on dry husks when disturbed and mass together and viciously bite any intruders. In return the rattan provides the ants with a place to nest and raise aphids, which turn feed on sap in the rattan and in turn excrete a liquid called honey dew that the ants feed on. [Source: David Attenborough, The Private Life of Plants, Princeton University Press, 1995]

Epiphytes and Bromelaids

Epiphytes are one of the most common types of plant found in the rainforest canopy. They are vascular plants that grows nonparasitically in the nooks and crannies of tree branches, deriving their nutrients from the air, the rain and the detritus on branches not from the living plant. There are over 29,000 species of epiphyte, falling into 83 families. More than 10 percent of all higher plants are epiphytes. In some highly developed rainforests large trees with large epiphyte trees growing on them and these in turn have more epiphytes growing on them and they in turn have a forth generation of bromeliads growing on them.

Bromeliads are one of the most common types of epiphyte. Technically herbs, because they lack woody tissue, they are anchored to trees with exposed roots and are found almost exclusively in the Western Hemisphere. Only one species is native to Africa. Even so, they come in a dazzling array of shapes, sizes and colors. Though most live in rainforests, they can be found in a variety of habitats, even deserts. Pineapples are bromeliads. Some of the larger species can hold 12 gallons of water.

Bromeliad Life

Bromeliad epiphyte on a cycadMany bromelaids trap rainwater and soil in pools between their leaves. Living in these pools are tree frogs with eggs on their backs, scorpions, seed shrimp, land crabs, multicolored slugs, snakes, lizards, worms, katydids, spiders, beetles, mosquitos, dragonfly nymphs, plants, mosses and lichens. Bromelaid do little danger to trees other than occasionally knocking down branches with their weight.

Many bromeliads have entire food chains prospering inside them with bacteria and algae that feed protozoa, which in turn feed small insects, which in turn feed frogs and snakes. The wastes of these creatures form soil, which supplies nutrients for the next generation or bromelaids.

David Attenborough wrote in The Private Life of Plants, "Their long leaves grow in a tight rosette around the central bud and channel rain water to it so that rosette fills and forms a small pond. This becomes a world in miniature. Leaves and other bits of vegetable detritus fall into and decay. Bird and small mammals come to sip the water. Microscopic organisms of one kind or another develop in any pool of standing water, Mosquitos lay rafts of eggs that float on the surface. Dragonflies deposit their eggs in its depths...Crabs, salamanders, slugs, worms, beetles, lizards and even small snails may join the community."

Ferns and Cycads

Ferns were among the earliest woody plants. They emerged about 350 million years ago, long before the dinosaurs and flowering plants. Some were the size of trees. Ferns have a different vocabulary to describe them than trees. Their leaves are called fonds. Their stems are known as rhizomes.

Found in a variety of habitats, ferns have stems with strong woody vessels that transport water and allow the plant to grow upwards to obtain light. There are both deciduous and evergreen varieties. Most ferns thrive in the shade and do best in wooded areas, where they can grow in great multitudes on the forest floor.

Ferns reproduce without flowers or seeds. Instead they produce millions of microscopic spores that are each a single-celled organism. Ferns grow in a complex two-stage growing process that wasn’t even understood until powerful microscopes were invented. First, the spores develop into filmy plants called thalluses that release sex cells from their underside, where there is usually a constant supply of moisture. Second, after the eggs have been fertilized, they grow into tall plants like the previous spore-producing generation.

Cycads look like ferns. Some individuals produce pollen. Other produce egg-bearing cones that remain attached to the parent. When the pollen lands of the cone it develops into a long tube which burrows into the cone over several months. When the tube is complete the largest known sperm (with individuals visible to the naked eye) are produced and they fertilize the eggs

Disturbed Rainforest and Gap Specialists

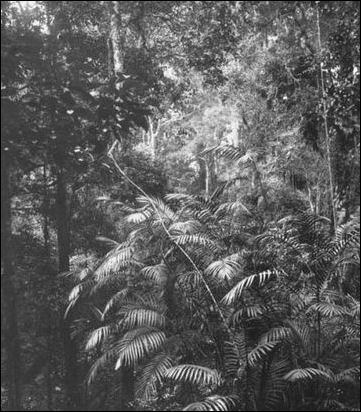

bird's nest fern Forests are disturbed by things like falling branches, broken off by wind or the weight of waterlogged epiphytes; heavy or diseased trees falling in shallow wet soil; burning after lightning storms; and clearing by loggers, ranchers or farmers.

In disturbed forest the remaining trees are often blown down and understory plants grow rapidly with exposure to sunlight. Tough, weedy pioneer plants invade and the "supertramp" insect populations skyrocket. An "edge effect" significantly alters the forest for at least 300 feet from the disturbed area, increasing the number of plants, animals and insects but reducing the number of species. An area in the deep rainforest might have 1,000 kinds of beetles while an area of similar size in the disturbed area might have only 300.

Some kinds of plant, called gap specialists, thrive in gaps created by physical disturbances. "When the canopy is broken up, sunlight falls more abundantly on the ground, and a new burst of vegetation springs up," Wilson wrote. "The species of trees and smaller plants in this assemblage are mostly different from those in the surrounding mature forest. So are many of the insects and animals that live on these gap specialists." [Source “Rainforest Canopy, the High Frontier” by Edward O. Wilson, National Geographic, December 1991 ▸]

Gap specialist grow thick and dominate deforested areas, river banks and clearings. They grow quickly, creating the so called impenetrable jungle. Eventually they die out when slower growing canopy trees mature, robbing the gap trees of sunlight. A mature forest at ground level is dark and has few obstacles. It is possible to walk in all directions without problems. It is only in the dense gap-filled forests that you need a machete.▸

Some scientist believe the disturbed areas may in fact be vital areas for the evolution of new rainforest species, stronger and tougher and adapted to new environments.

Fungi

Fungi are neither plants or animals. They do not engage in photosynthesis and thus are not plants, and and more like animals in this respect in that they consume food from the outside and can not produce it themselves as plants can. Most are fungi not parasites, which absorb nutrients from living hosts. In fact fungi plays an important role breaking down rotten materials to that its nutrients can be absorbed by plants. Fungi cells divide in such a unique way that fungi occupies its own kingdom (along with plants and animals): Mycota. There may be as many as 1.5 million fungus species. Most are unseen cavities found in the soil. Only around 10 percent have ever described in science. Researchers are looking more and more to mushrooms and fungi as sources of medicine. [Source: Darlyne Murawski, National Geographic, August 2000]

Fungi have no stems, roots or leaves and composed not of cellulose, like plants, but of chitin, the material insects and crabs used to make their shells. Fungi grow by absorbing nutrients from its usually dead hosts. They live off of breaking organic material in soil, leaf liter, dead wood and even animal dung. Many fungi use enzymes to breakdown organic compounds into food they can consume.

Hua Hsu wrote in The New Yorker: “Fungus is everywhere, yet easy to miss. Mushrooms are the most glamorous but possibly least interesting members of this kingdom. Most fungi take the form of tiny cylindrical threads, from which hyphal tips branch in all directions, creating a meandering, gossamer-like network known as mycelium. Fungus has been breaking down organic matter for millions of years, transforming it into soil. A handful of healthy soil might contain miles of mycelia, invisible to the human eye...Before any plants were taller than three feet, and before any animal with a backbone had made it out of the water, the earth was dotted with two-story-tall, silo-like fungi called prototaxites. The largest living organism on earth today is a fungus in Oregon just beneath the ground, covering about 3.7 square miles and estimated to weigh as much as thirty-five thousand tons. If fungus can inspire awe, it can also be a nuisance or worse, from athlete’s foot to the stem rust that afflicts wheat and is considered a major threat to global food security. Last year, the C.D.C. identified the Candida auris as an emerging public-health concern; it’s a sometimes fatal, drug-resistant pathogen that has emerged in hospitals and nursing homes around the world. The more we learn about fungi the less the natural world makes sense without them. [Source: Hua Hsu, The New Yorker, May 18, 2020]

“Fungi are humble yet astonishingly versatile organisms, “eating rock, making soil, digesting pollutants, nourishing and killing plants, surviving in space, inducing visions, producing food, making medicines, manipulating animal behavior, and influencing the composition of the earth’s atmosphere.” Plants make their own food, converting the world around them into nutrients. Animals must find their food. But fungi essentially acquire theirs by secreting digestive enzymes into their environment, and absorbing whatever is nearby: a rotten apple, an old tree trunk, an animal carcass. If you’ve ever looked closely at a moldy piece of bread—mold, like yeast, being a type of fungus—what appears to be a layer of fuzz is actually millions of minuscule hyphal tips, busily breaking down matter into nutrients.

Book: “Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures” by Merlin Sheldrake (Random House, 2020)

Mushrooms and Fungi Reproduction

Mushrooms are the reproductive structures of fungi. The actual fungi are usually a string or net of filaments called mycelium, which are found under leaves, on the forest floor or inside or under rotted logs. Fungi reproduce with spores that in many cases are cast off to the wind. Some are ingested by animals and grow in the animal's dung. Hua Hsu wrote in The New Yorker: “This is where mushrooms show their prowess. The shaggy inkcap mushroom—soft and tender when cooked—can break through asphalt and concrete pavement. Each year, fungi produce more than fifty megatons of spores. Some mushrooms are capable of onetime exertions in which spores are catapulted through the air at speeds of fifty-five miles an hour. But the contribution that fungi make to the larger ecology is fundamental: by turning biomass into soil, they recycle dead organic matter back into organic life. [Source: Hua Hsu, The New Yorker, May 18, 2020]

Fungi spend most of their time underground. Mushrooms are the fungi equivalent of flowers, They generally sprout suddenly and last for only a few days. The produce spores, not seeds, which carry no food and capable of fertilizing themselves. Spores are microscopic or nearly so and a single mushroom may produce millions of them.

A simple field mushroom in the wild might released 100 million spores from its plate-like gills in an hour and 16 billion before it decays. A giant puffball, 30 centimeters across, may release a billion spores in each buff and 7 trillion in a single session. The mycelium spreads out until two fungi unit and send up reproductive structures, the mushrooms.

Fungi Communication and Behavior?

Hua Hsu wrote in The New Yorker: Cambridge-trained biologist Merlin Sheldrake "notes that the hyphal tips of mycelium seem to communicate with one another, making decisions without a real center. He describes an experiment conducted a couple of years ago by a British computer scientist, Andrew Adamatzky, who detected waves of electrical activity in oyster mushrooms, which spiked sharply when the mushrooms were exposed to a flame. Adamatzky posited that the mushroom might be a kind of “living circuit board.” The point isn’t that mushrooms would replace silicon chips. But if fungi already function as sensors, processing and transmitting information through their networks, then what could they potentially tell (or warn) us about the state of our ecosystem, were we able to interpret their signals? [Source: Hua Hsu, The New Yorker, May 18, 2020]

“Sheldrake also tells us about Toby Kiers, an evolutionary biologist who was taken with Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” and its insights on inequality. She wondered how mycorrhizal networks, the symbiotic intertwining of plant systems and mycelium, deal with their own, natural encounters with inequity. Kiers exposed a single fungus to an unequally distributed supply of phosphorus. Somehow the fungus “coordinated its trading behavior across the network,” Sheldrake writes, essentially shuttling phosphorus to parts of the mycelial network for trade with the plant system according to a “buy low, sell high” logic.

“Scientists still don’t understand how fungi coördinate, control, and learn from such behaviors, just that they do. “How best to think about shared mycorrhizal networks?” Sheldrake wonders. “Are we dealing with a superorganism? A metropolis? A living Internet? Nursery school for trees? Socialism in the soil? Deregulated markets of late capitalism, with fungi jostling on the trading floor of a forest stock exchange? Or maybe it’s fungal feudalism, with mycorrhizal overlords presiding over the lives of their plant laborers for their own ultimate benefit.” None of these attempts to fit fungi into the logic of our world are entirely persuasive. Perhaps it’s the other way around, and we’re the ones who should try to fit into the fungus’s model. A truffle’s funky aroma evolved to attract insects and small rodents, which feast on the spores, then spread them throughout the forest via their fecal matter. For many, the pleasure of psilocybin is in giving oneself up to the weft of a connected world, and making peace with one’s smallness.

Mosses

Mosses are filaments. They lack rigidity and often pack themselves together to form cushiony surfaces. Based on discoveries made from a 300-million-year-old fossilized forest found in a coal seem in Illinois, club mosses grew over a meter thick and 40 meters high in primordial rainforests.

Mosses and liverworts practice two kinds of reproduction: sexual and asexual, in alternative generations. Green moss produces sex cells. Each large eggs remains attached to the stem at the top. The microscopic sperm are released into the water and wriggle their way to the egg to fertilize it. The egg then germinates while still attached to parent plant to produce the next asexual generation: a thin stem with a hollow capsule at the top.

Mosses produces spores in small capsules at the top of it stem. When the are ready to releases a lid springs on the top to reveal a ring of teeth covering a mouth beneath it. If the weather is warm and dry the teeth dry out and curl backwards, opening the capsule and allowing the spores to blow away. If the weather is wet, the spores could become waterlogged and not carry far. To prevent this from happening the teeth reabsorb moisture and shut the capsule.

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); National Geographic articles. Also the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2024