WORLD'S BIGGEST TREES

According to a study published in Nature in 2015, there are over 3 trillion trees in the world. The largest trees are defined as having the highest wood volume in a single stem. These trees are both tall and large in diameter and, in particular, hold a large diameter high up the trunk. Measurement is very complex, particularly if branch volume is to be included as well as the trunk volume, so measurements have only been made for a small number of trees, and generally only for the trunk. Few attempts have ever been made to include root or leaf volume. [Source Wikipedia]

All 12 of the world's largest trees are giant sequoias (Sequoiadendron giganteum). Grogan's Fault, the largest living Coast redwood, would rank as the 13th largest living tree. Tāne Mahuta, the largest living tree outside of California, would rank within the top 100 largest living trees.

The General Sherman Tree — giant sequoia in Sequoia National Park, California — is the world's largest tree by volume, at 1,487 cubic meters 52,508 cubic feet). Located at an elevation of 2,109 meters (6,919 feet) above sea level, it is 2,200 years old and measures 83.8 meters (274.9 fee) tall, 31.1 meters (102.6 fee) circumference at ground and 11.1 meters (36.5 fee) maximum diameter at base.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

AMAZON: RIVER, FOREST, HISTORY, ECOLOGY factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST TREES, FRUITS, PLANTS AND BAMBOO factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST LIANAS, FIGS, EPIPHYTES, FERNS, BROMELAIDS AND FUNGI factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST ORCHIDS AND FLOWERS factsanddetails.com

Tallest Trees in the World

The tallest trees on Earth are the coastal redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) in northern California and the biggest one of them all is a giant known as Hyperion, according to Guinness World Records, when it was last measured in 2019, it was 116.07 meters (380 feet, 9.7 inches) tall from top to base — taller than a 35-story building. Hyperion's exact location is a closely guarded secret, but it is apparently situated in a hillside in the Redwood National Park on which most of the old-growth coastal redwoods had been logged. The tree is estimated to be between 600 and 800 years old. The tree is named after Hyperion. one of the Titans in Greek mythology, [Source Tia Ghose, Live Science, May 24, 2022]

Tia Ghose wrote in Live Science: The living skyscraper was first discovered in 2006, by Chris Atkins and Michael Taylor, part of a team of researchers who, at the time, tramped through the California forests hunting for the tallest trees, SFGate reported. At that time, the tree was a tiny bit shorter, at 379 feet, 1.2 in (115.5 meters). Around the same time, that group discovered the second and third-tallest trees: Helios, which was then 376.3 feet (114.7 meters) tall, and Icarus, which stood 371.2 feet (113.1 meters) tall. "Even though they're on steep slopes, they're growing in the finest redwood habitat on the planet," Atkins told SFGate in 2006. "They're right below a ridge, so they're protected from the wind. They're near abundant water, and they have plenty of fog, which keeps the local microclimate mild and moist. And they have great sun exposure."

Coast redwoods are not only the tallest trees on the planet, they are also some of the oldest living things on Earth; they can live up to 2,000 years. It's not clear exactly why these trees can live to be so ancient, but the climate plays a role. Even when inland California burns in the summer, a blanket of thick fog enshrouds the coastal groves, keeping the temperature cool year-round. The coast also sees about 100 inches (254 centimeters) of rainfall a year, which also helps nurture these groves of giants, according to the National Park Service.

Coast redwoods are also some of the most resilient trees on Earth. Their tannin-rich bark seems to be nearly impervious to the fungus and disease that fells other trees, according to the NPS. And the 12-inch-thick (25 cm) bark of these silent giants enables them to withstand the wildfires that have historically swept through the Sierras.

The tallest trees on other continents, according to Guinness World Records, are:

Asia: The tallest tree in Asia a yellow meranti tree (Shorea faguetiana) found in Sabah, Malaysia. It is a bit taller than Australia's tallest tree, at 100.8 meters (330 feet) tall. A taller tree has been found in China. See Below

Australia: A Eucalyptus regnans found on the island of Tasmania, which stands 99.82 meters (327.5 feet) tall, is Australia's tallest tree.

South America: A red angelim (Dinizia excelsea) tree in Brazil's Amazon rainforest is the tallest on the continent, at 88.5 meters (290.4 feet)

Africa: A myovo tree (Entandrophragma excelsum) near Kilimanjaro National Park in Tanzania stands 81.50 meters (267.4 feet) tall

Europe: The largest tree there lives in Portugal. This Karri tree (Eucalyptus diversicolor) stands 72.9 meters (239.2 feet) tall.

Asia's Tallest Tree Found in Tibet in the World's Deepest Canyon

A cypress tree in in a forested area of Tibet is the tallest tree ever discovered in Asia. It is also believed to be the second-tallest tree in the world, standing at an astonishing 102 meters (335 feet) tall — taller than the Statue of Liberty, which stands is 93 meters (305 feet) tall. Lydia Smith, Live wrote in Live Science: The gigantic cypress was discovered in May, 2023 by a Peking University research team at the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon nature reserve in Bome County, Nyingchi City, in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. , according to a statement released by the university. The tree is 9.6 feet (2.9 meters) in diameter, according to the state-run Chinese publication the People's Daily Online. The species the cypress belongs to is unclear, although Chinese state media publications suggested it is either a Himalayan cypress (Cupressus torulosa) or a Tibetan cypress (Cupressus gigantea).

Before this discovery, Asia's tallest tree was a 331-foot-tall (101 meters) yellow meranti (Shorea faguetiana) located in the Danum Valley Conservation Area in Sabah, Malaysia. The Tibet Autonomous Region has a unique ecosystem that is increasingly influenced by development and global climate change. However, the area — and in particular Nyingchi City — has recently been the focus of conservation efforts to protect flora and fauna. The Peking University researchers have documented tall trees in the region to better understand the area's environmental diversity and to help ecological protection efforts, the statement said.

In 2022, the team found a 272-foot-tall (83 meters) fir tree in southwest China, which they initially believed was the largest tree in China. The team also uncovered a 252-foot (77 meters) tree in Medog County a month earlier. Continuing their survey in 2023, the researchers used drones, lasers and radar equipment to map out the trees in the area and identify their heights from the ground. After days of field surveys, the cypress was found and confirmed as the tallest tree in Asia. Using drones, a 3D laser scanner and lidar technology — which uses light beams to provide distance measurements — the team created a 3D model of the enormous tree, providing accurate dimensions. Using this, they confirmed it was the tallest tree in Asia.

Guo Qinghua, a professor at the Institute of Remote Sensing of Peking University, told state newspaper the Global Times that the tree is interesting because its supporting roots are not completely buried underground. The tree also has a complex branching system that provides "ideal microclimates and habitats for some endangered plants and animals," a university statement said.

Oldest Trees in the World

It's not always easy to study and date them. Tropical trees, for example, don't have the clearly delineated rings like the trees in temperate regions where there are clear seasons do. Even in areas where trees are well-studied, scientists may not know the trees' ages.

The world's oldest trees were already hundreds of years old when the Great Pyramids of Giza were built and thousands of years old when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon. Erik Ofgang wrote in Live Science: To determine a tree's age, scientists collect a core sample from the plant's base and then count its rings. This dating of tree rings is called dendrochronology and it can be a valuable tool for measuring tree age and studying environmental changes over time. However, due to rotting and the thickness of a tree’s trunk, it's not always possible to get complete cores. Often tree ages are determined after it has died, but it is possible to get a core without killing it with a specialist tool that can extract a very narrow sample. Here are the longest-lived trees ever to be discovered on Earth.[Source: Erik Ofgang, Live Science, May 29, 2023]

1) Prometheus (at least 4,900 years old when it was cut down): Prometheus, a Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) in Wheeler Peak, Nevada, lived close to 5,000 years before it was cut down in 1964. It remains the longest-lived tree definitively documented. Prometheus met its end when geographer Donald R. Currey, who was studying ice age glaciology and had been granted permission to take core samples from pines in the park, cut it down (also with permission). Currey counted 4,862 rings and estimated the tree was more than 4,900-years-old.The stump Currey used to count the rings was not taken from the very bottom of the tree, so the tree was certainly older than 4,862 years.

After the tree was brought down. There are differing accounts as to why the tree was felled, according to the National Park Service. The most popular version is that Currey's coring tool got stuck and he cut down the tree as a result. Others suggest he cut down the tree to get a better count of its rings. Today, a piece of the tree can be viewed at the Great Basin Visitor Center in Nevada at the Great Basin National Park.

2) Methuselah (at least 4,600 years old): Since 1957, this bristlecone pine has held the title of the world's oldest living tree. Methuselah was discovered by famed tree researcher Edmund Schulman, a scientist at the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona. He found Methuselah's age after taking cores from many bristlecones in the area and counting the rings. To protect Methuselah from tourists, who might damage the tree by touching it or walking near its roots, the U.S. Forest Service has long kept Methuselah's exact location a secret and does not release photographs of it. The tree is somewhere along the 4.5-mile (7.2 kilometers) Methuselah Trail in the White Mountains of Inyo National Forest in California.

Is "Great Grandfather" in Chile the World’s Oldest Tree?

In April 2022, AFP reported: In a forest in southern Chile, a giant tree has survived for thousands of years and is in the process of being recognized as the oldest in the world. Known as the "Great Grandfather," the trunk of this tree measuring four meters (13 feet) in diameter and 28 meters tall is also believed to contain scientific information that could shed light on how the planet has adapted to climatic changes.

Believed to be more than 5,000 years old, it is on the brink of replacing Methuselah, a 4,850-year-old Great Basin bristlecone pine found in California in the United States, as the oldest tree on the planet. "It's a survivor, there are no others that have had the opportunity to live so long," said Antonio Lara, a researcher at Austral University and Chile's center for climate science and resilience, who is part of the team measuring the tree's age. [Source: Paulina Abramovich, AFP, April 22, 2023]

The Great Grandfather lies on the edge of a ravine in a forest in the southern Los Rios region, 800 kilometers (500 miles) to the south of the capital Santiago. It is a Fitzroya cupressoides, a type of cypress tree that is endemic to the south of the continent. In recent years, tourists have walked an hour through the forest to the spot to be photographed beside the new "oldest tree in the world."

Due to its growing fame, the national forestry body has had to increase the number of park rangers and restrict access to protect the Great Grandfather. By contrast, the exact location of Methuselah is kept a secret. Also known as the Patagonian cypress, it is the largest tree species in South America. It lives alongside other tree species, such as coigue, plum pine and tepa, Darwin's frogs, lizards, and birds such as the chucao tapaculo and Chilean hawk.

Park warden Anibal Henriquez discovered the tree while patrolling the forest in 1972. He died of a heart attack 16 years later while patrolling the same forest on horseback. "He didn't want people and tourists to know (where it was) because he knew it was very valuable," said his daughter Nancy Henriquez, herself a park warden. Henrique's nephew, Jonathan Barichivich, grew up playing amongst the Fitzroya and is now one of the scientists studying the species. In 2020, Barichivich and Lara managed to extract a sample from the Great Grandfather using the longest manual drill that exists, but they did not reach the center. They estimated that their sample was 2,400 years old and used a predictive model to calculate the full age of the tree. Barichivich said that "80 percent of the possible trajectories show the tree would be 5,000 years old."

World’s Oldest Known Trees, Historically — 390 Million Years Old

In March 2024, scientists working in southwest England announced that they had found the oldest known fossilized forest, dating back 390 million years ago, according to press release from the University of Cambridge. The fossils The fossils were found in high sandstone cliffs on the southern side of the Bristol Channel near Minehead. They break the previous record held by a forest in New York state by 4 million years. [Source: Jack Guy, CNN, March 8, 2024]

Jack Guy wrote in CNN: The trees, known as Calamophyton, look fairly similar to palm trees but had thin, hollow trunks. They didn’t have any leaves, but had twig-like structures covering their branches, study first author Neil Davies, a lecturer at the University of Cambridge’s Earth Sciences department, told CNN. They would reach up to 2-4 meters (6.6-13.1 feet) tall and shed branches as they grew. The forest dates from the Devonian Period, 419 million to 358 million years ago, when life was moving onto land.

The trees would have trapped sediment in their root systems, stabilizing riverbanks and coastlines, Davies explained. “In doing so they are corralling water in certain locations and making these small channels,” he said. “They’re basically building the environment they want to live in rather than being passive.”

The findings also reveal the speed with which early forests developed, said Davies. While the fossils in England are from a sparse forest with just one type of tree, the previous oldest forest in New York state had more variety of species, such as vine-like trees that grew on the ground, despite living just 4 million years later, he explained. “By comparing the Somerset flora with the New York flora you really see how rapidly things changed in terms of geological time,” said Davies. “Within a kind of geological blink of the eye you’ve got a lot more variety,” he added.

The trees also provided a habitat for invertebrates living on the forest floor thanks to the twigs that would drop on the ground. The team found evidence of footprints and tail drags left by these early anthropods, said Davies. While scientists don’t know exactly what they were due to a lack of physical remains, the largest ones were around 5-10 centimeters (2-4 inches) wide, said Davies. “They’re sizeable,” he added. The team also found evidence that the arthropods would bury themselves in the sediment on the forest floor to prevent themselves drying out in the very warm, semi-arid climate, said Davies.

Scientists Say There Are 73,300 Tree Species in the World

In early 2022, researchers unveiled the world's largest forest data base, comprising more than 44 million individual trees at more than 100,000 sites in 90 countries — and calculated that the Earth is home roughly 73,300 tree species — about 14 percent higher than previous estimates. Of that total, about 9,200 are estimated to exist based on statistical modeling but have not yet been identified by science, with a large proportion of these growing in South America.[Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, February 1, 2022]

South America, home to the enormously biodiverse Amazon rainforest and farflung Andean forests, was found to harbor 43 percent of the planet's tree species and the largest number of rare species, at about 8,200. “Trees and forests are much more than mere oxygen producers, said Roberto Cazzolla Gatti, a professor of biological diversity and conservation at the University of Bologna in Italy and lead author of the study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "Without trees and forests, we would not have clean water, safe mountain slopes, habitat for many animals, fungi and other plants, the most biodiverse terrestrial ecosystems, sinks for our excess of carbon dioxide, depurators of our polluted air, et cetera," Gatti said.

Reuters reported: “South America was found to have about 27,000 known tree species and 4,000 yet to be identified. Eurasia has 14,000 known species and 2,000 unknown, followed by Africa (10,000 known/1,000 unknown), North America including Central America (9,000 known/2,000 unknown) and Oceania including Australia (7,000 known/2,000 unknown). "By establishing a quantitative benchmark, our study can contribute to tree and forest conservation efforts," said study co-author Peter Reich, a forest ecologist at the University of Michigan and University of Minnesota. "This information is important because tree species are going extinct due to deforestation and climate change, and understanding the value of that diversity requires us to know what is there in the first place before we lose it," Reich said. "Tree species diversity is key to maintaining healthy, productive forests, and important to the global economy and to nature."

The study pinpointed global tree diversity hot spots in the tropics and subtropics in South America, Central America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It also determined that about a third of known species can be classified as rare. The researchers used methods developed by statisticians and mathematicians to estimate the number of unknown species based on the abundance and presence of known species. Tropical and subtropical ecosystems in South America may nurture 40 percent of these yet-to-be-identified species, they said. "This study reminds us how little we know about our own planet and its biosphere," said study co-author Jingjing Liang, a professor of quantitative forest ecology at Purdue University in Indiana. "There is so much more we need to learn about the Earth so that we can better protect it and conserve natural resources for future generations."

Unusual Trees

The Cook pine (Araucaria columnaris) is the only species that seems to orient itself globally toward the equator. Stems lean to the south in California, to the north in Australia, and hardly at all in Hawaii. The Rainbow eucalyptus is found in the rainforests of Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and the Philippines. It is so named because every summer, its outer skin to reveal shades of greens, yellows, reds, oranges and even pink in its underlying bark. Banyan (Ficus benghalensis) trees are native to India but have been planted elsewhere. To support its sprawling canopy, the banyan tree sprouts special above-ground roots that help prop up its heavy branches. One famous specimen, known as The Great Banyan, has a a canopy larger than three football fields.

The Dragon's blood tree (Dracaena cinnabari) is sometimes called the umbrella tree. Native to Yemen and designated as vulnerable but not endangered, it is named for the crimson sap that it produces — the dragon's blood. Its umbrella shape is a manifestation of the trees upside-down existence. While most trees draw water from the soil through their roots, the dragon’s blood tree does the reverse. It absorbs moisture from the air and channels it toward its root system. [Source Conservation International]

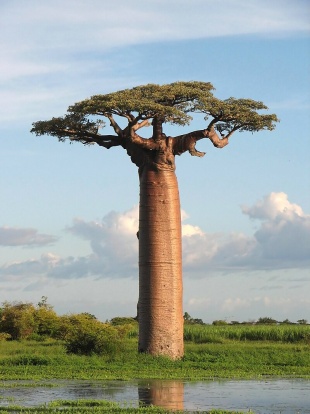

Baobab trees are famous for their enormous, cylindrical trunk, which allow them to store water during dry periods. In times of heavy rainfall, its trunk can span up to 3 meters across. Although they are know as a mainland African tree, only one species grows there, whereas Madagascar boasts six. According to an African legend, the baobab tree somehow offended God and was punished by being tuned upside down. The pulpy fruit, called monkey bread, is fermented into an alcoholic beverage and the bark is used to make clothes, paper, rope and medicine.

The tallest baobab trees are called the "mother of the forest" by Madagascar’s Antandroy people. The steadily shrinking baobab forests are hard to replenish. The trees live for centuries but don't fruit every year. Even when they do fruit seedlings often die during freak dry spells. It is estimated that a seedling lives long that a couple months once every five to ten years. If they get this far many fall prey to Madagascar giant jumping rats.

Do Trees Belong to Communities?

Peter Wohlleben, a German forester and author of the controversial but popular book “The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate” argues that trees form communities and communicate with one another. Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“Since Darwin, we have generally thought of trees as striving, disconnected loners, competing for water, nutrients and sunlight, with the winners shading out the losers and sucking them dry. The timber industry in particular sees forests as wood-producing systems and battlegrounds for survival of the fittest.[Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

“There is now a substantial body of scientific evidence that refutes that idea. It shows instead that trees of the same species are communal, and will often form alliances with trees of other species. Forest trees have evolved to live in cooperative, interdependent relationships, maintained by communication and a collective intelligence similar to an insect colony. These soaring columns of living wood draw the eye upward to their outspreading crowns, but the real action is taking place underground, just a few inches below our feet. “Some are calling it the ‘wood-wide web,’” says Wohlleben in German-accented English. “All the trees here, and in every forest that is not too damaged, are connected to each other through underground fungal networks. Trees share water and nutrients through the networks, and also use them to communicate. They send distress signals about drought and disease, for example, or insect attacks, and other trees alter their behavior when they receive these messages.”

“Scientists call these mycorrhizal networks. The fine, hairlike root tips of trees join together with microscopic fungal filaments to form the basic links of the network, which appears to operate as a symbiotic relationship between trees and fungi, or perhaps an economic exchange. As a kind of fee for services, the fungi consume about 30 percent of the sugar that trees photosynthesize from sunlight. The sugar is what fuels the fungi, as they scavenge the soil for nitrogen, phosphorus and other mineral nutrients, which are then absorbed and consumed by the trees.

“For young saplings in a deeply shaded part of the forest, the network is literally a lifeline. Lacking the sunlight to photosynthesize, they survive because big trees, including their parents, pump sugar into their roots through the network. Wohlleben likes to say that mother trees “suckle their young,’’ which both stretches a metaphor and gets the point across vividly.

“Once, he came across a gigantic beech stump in this forest, four or five feet across. The tree was felled 400 or 500 years ago, but scraping away the surface with his penknife, Wohlleben found something astonishing: the stump was still green with chlorophyll. There was only one explanation. The surrounding beeches were keeping it alive, by pumping sugar to it through the network. “When beeches do this, they remind me of elephants,” he says. “They are reluctant to abandon their dead, especially when it’s a big, old, revered matriarch.”

Tree Communication?

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “To communicate through the network, trees send chemical, hormonal and slow-pulsing electrical signals, which scientists are just beginning to decipher. Edward Farmer at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland has been studying the electrical pulses, and he has identified a voltage-based signaling system that appears strikingly similar to animal nervous systems (although he does not suggest that plants have neurons or brains). Alarm and distress appear to be the main topics of tree conversation, although Wohlleben wonders if that’s all they talk about. “What do trees say when there is no danger and they feel content? This I would love to know.” Monica Gagliano at the University of Western Australia has gathered evidence that some plants may also emit and detect sounds, and in particular, a crackling noise in the roots at a frequency of 220 hertz, inaudible to humans. [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

“Trees also communicate through the air, using pheromones and other scent signals. Wohlleben’s favorite example occurs on the hot, dusty savannas of sub-Saharan Africa, where the wide-crowned umbrella thorn acacia is the emblematic tree. When a giraffe starts chewing acacia leaves, the tree notices the injury and emits a distress signal in the form of ethylene gas. Upon detecting this gas, neighboring acacias start pumping tannins into their leaves. In large enough quantities these compounds can sicken or even kill large herbivores.

“Giraffes are aware of this, however, having evolved with acacias, and this is why they browse into the wind, so the warning gas doesn’t reach the trees ahead of them. If there’s no wind, a giraffe will typically walk 100 yards — farther than ethylene gas can travel in still air — before feeding on the next acacia. Giraffes, you might say, know that the trees are talking to one another.

“Trees can detect scents through their leaves, which, for Wohlleben, qualifies as a sense of smell. They also have a sense of taste. When elms and pines come under attack by leaf-eating caterpillars, for example, they detect the caterpillar saliva, and release pheromones that attract parasitic wasps. The wasps lay their eggs inside the caterpillars, and the wasp larvae eat the caterpillars from the inside out. “Very unpleasant for the caterpillars,” says Wohlleben. “Very clever of the trees.”

“A recent study from Leipzig University and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research shows that trees know the taste of deer saliva. “When a deer is biting a branch, the tree brings defending chemicals to make the leaves taste bad,” he says. “When a human breaks the branch with his hands, the tree knows the difference, and brings in substances to heal the wound.”

Tree Families?

bamboo forestYoung beech trees, in their own individual ways, are tackling the fundamental challenge of their existence. Like any tree, they crave sunlight, but down here below the canopy, only 3 percent of the light in the forest is available. One tree is the “class clown.” Its trunk contorts itself into bends and curves, “making nonsense” to try to reach more light, instead of growing straight and true and patient like its more sensible classmates. “It doesn’t matter that his mother is feeding him, this clown will die,” says Wohlleben.

“Another tree is growing two absurdly long lateral branches to reach some light coming through a small gap in the canopy. Wohlleben dismisses this as “foolish and desperate,” certain to lead to future imbalance and fatal collapse. He makes these blunders sound like conscious, sentient decisions, when they’re really variations in the way that natural selection has arranged the tree’s unthinking hormonal command system

“Mother trees are the biggest, oldest trees in the forest with the most fungal connections. They’re not necessarily female, but Simard sees them in a nurturing, supportive, maternal role. With their deep roots, they draw up water and make it available to shallow-rooted seedlings. They help neighboring trees by sending them nutrients, and when the neighbors are struggling, mother trees detect their distress signals and increase the flow of nutrients accordingly.

At the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Suzanne Simard and her grad students are making astonishing new discoveries about the sensitivity and interconnectedness of trees in the Pacific temperate rainforests of western North America. Peter Wohlleben has referred extensively to her research in his book. Using seedlings, Amanda Asay one of Sinard’s grad students, and fellow researchers have shown that related pairs of trees recognize the root tips of their kin, among the root tips of unrelated seedlings, and seem to favor them with carbon sent through the mycorrhizal networks. “We don’t know how they do it,” says Simard. “Maybe by scent, but where are the scent receptors in tree roots? We have no idea.”

“Not all scientists are on board with the new claims being made about trees. Where Simard sees collaboration and sharing, her critics see selfish, random and opportunistic exchanges. Stephen Woodward, a botanist from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, warns against the idea that trees under insect attack are communicating with one another, at least as we understand it in human terms. “They’re not firing those signals to anything,” Woodward says. “They’re emitting distress chemicals. Other trees are picking it up. There’s no intention to warn.”

“Lincoln Taiz, a retired professor of plant biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz and the co-editor of the textbook Plant Physiology and Development, finds Simard’s research “fascinating,” and “outstanding,” but sees no evidence that the interactions between trees are “intentionally or purposefully carried out.” Nor would that be necessary. “Each individual root and each fungal filament is genetically programmed by natural selection to do its job automatically,” he writes by email, “so no overall consciousness or purposefulness is required.” Simard, it should be noted, has never claimed that trees possess consciousness or intention, although the way she writes and talks about them makes it sound that way.

Japanese Scientists Video Plants Communicating

In October 2023, in a study published in the journal Nature Communications, a group of Japanese scientists announced that they had successfully videoed plants communicating and warning others about potential dangers in real-time. Bryan Ke wrote in NextShark: The research team, led by molecular biologist Masatsugu Toyota from Japan's Saitama University, successfully captured undamaged plants sending defense responses to nearby plants after sensing volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are produced by other plants in response to mechanical damages or insect attacks. [Source: Bryan Ke, NextShark, January 17, 2024]

The team, which included Yuri Aratani, a Ph.D. student at the university, and Takuya Uemura, a postdoctoral researcher, attached an air pump to a container filled with leaves and caterpillars and to another chamber containing Arabidopsis thaliana, a common weed from the mustard family. The Arabidopsis was genetically modified to make their cells fluoresce green after detecting calcium ions, which serve as stress messengers. The team then used a fluorescence microscope to monitor the signals the undamaged plants released after receiving VOCs from the damaged leaves.

Plant communication was first observed in a study in 1983. “We have finally unveiled the intricate story of when, where and how plants respond to airborne 'warning messages' from their threatened neighbors,” Toyota said of their recent study. “This ethereal communication network, hidden from our view, plays a pivotal role in safeguarding neighboring plants from imminent threats in a timely manner.”

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com ; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); National Geographic articles. Also the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2024