STUDYING THE RAINFOREST

A group of professors wrote in The Conversation: Tropical forests are more than just trees — they are complex, dynamic networks of plants, animals and microbes. Active research areas typically emphasize how specific features of forests, such as the number of species they contain or tree biomass, change over time and space. [Source: Robin Chazdon, Professor Emerita of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Catarina Conte Jakovac, Associate professor of Plant Science, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Lourens Poorter, Professor of Functional Ecology, Wageningen University, The Conversation, and Bruno Hérault, Tropical Forest Scientist, Forests & Societies Research Unit, Cirad, The Conversation December 10, 2021]

Important components a key areas of study within them include: 1) Soil: How much organic carbon and nitrogen does it contain, and how compacted is it? Soil that is too densely compacted — for example, by the hooves of grazing cattle — is hard for plant roots to penetrate and doesn’t absorb water well, which can lead to erosion. 2) Ecosystem functioning: How does the abundance and size of trees change as the forest regrows? What is the role in forest regrowth of trees that have root associations with nitrogen-fixing bacteria? How does regrowth affect the average density of wood and the durability of leaf tissues?

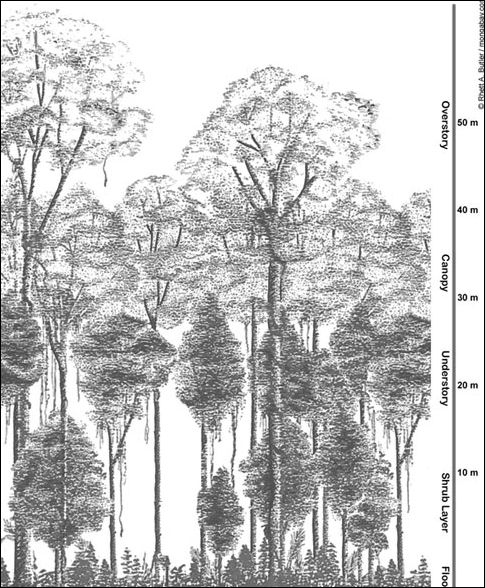

3) Forest structure: How do maximum tree size, variation in tree size, and total biomass — the quantity of plant matter above ground in tree trunks, branches and leaves — change as forests regrow? 5) Diversity and composition of tree species: How do the numbers of tree species present and the diversity and abundance patterns of species change and become more similar to nearby old-growth forests?

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

BIODIVERSITY AND THE NUMBER OF SPECIES factsanddetails.com ;

AMAZON: RIVER, FOREST, HISTORY, ECOLOGY factsanddetails.com ;

TREES: OLDEST, TALLEST, UNUSUAL SPECIES, COMMUNICATION factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST TREES, FRUITS, PLANTS AND BAMBOO factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST LIANAS, FIGS, EPIPHYTES, FERNS, BROMELAIDS AND FUNGI factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST ORCHIDS AND FLOWERS factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Rainforest Action Network ran.org ; Rainforest Foundation rainforestfoundation.org ; World Rainforest Movement wrm.org.uy ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Forest Peoples Programme forestpeoples.org ; Rainforest Alliance rainforest-alliance.org ; Nature Conservancy nature.org/rainforests ; National Geographic environment.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rainforest-profile ; Rainforest Photos rain-tree.com ; Rainforest Animals: Rainforest Animals rainforestanimals.net ; Mongabay.com mongabay.com ; Plants plants.usda.gov

Methods for Studying the Rainforest Canopy

rain forest soils Although it is the most biologically diverse place on the planet the canopy is still largely unexplored. Up until recently rainforest scientists were like oceanographers who studied their subject from land. In some cases they collected samples in the upper branches by blasting them down with shotguns or using trained monkeys to fetch them. Today, scientists are actually going up into the canopy with ropes and harnesses like those used rock climbers and belts and spiked boots like those used by telephone pole repairmen.

Describing these methods, David Attenborough wrote: "First, you must get a thin line over a high branch, either by throwing it or by attaching it to an arrow and shooting...Hauling pulls the rope over the branch. Once it has been securely tied, you clip on two metal hand grips. You can slide them upwards but a ratchet prevents them from slipping down wards. With your feet in webbing stirrups, one tied to each grip you slowly host your way up the rope."

Some scientists shun ropes in favor of platforms, steel towers and construction cranes. Observation posts have been set up on gondolas hanging off of aluminum booms, catwalks stretched between trees and bamboo platforms built on top of collapsible ladders. Some scientists have even set up networks of ropes between trees and move over a large area of the canopy to study microclimates and animals. In some cases they stay aloft for days at a time, eating and sleeping in the trees.

In 1989 a team of French scientists studied the canopy in the Amazon used an extraordinary, baseball-diamond-size airborne raft made of rubber pontoons and synthetic fiber netting. Designed by an architect and lowered by dirigible onto the canopy, the raft snuggled in nicely between the tree crowns where it received plenty of support. For safety the scientist were attached to ropes at all the time. To reach the rainforest floor they descended through "manholes" on ropes using hand clamps and harnesses. [Source: Francic Hallé, National Geographic, October 1990].

Studying Plants and Animals in the Rainforest

Biologists studying mammals identify animals by wandering through the forest at night listening for calls and looking for reflection of their eyes in their headlamps or by setting traps baited with bananas and peanut butter. The traps are raised to the canopy and lowered with a rope-and-pullet system.

Scientists collect insects using gasoline-powered foggers that look like leaf blowers and use a biodegradable insecticide that causes the insects to drop out of canopy onto plastic sheets below. The captured insects are later hauled to a laboratory where are counted and classified. Insects that are most active at night are attracted using black light. Butterflies are lured with traps that smell like their favorite rotten fruit and other flying insects are trapped in tin cans above ultra-violet light that force them to fly upwards.

Rainforest botanists spend most of their time collecting and identifying species. To gather samples they sometimes follow logging operations and gather life forms from recently felled trees or observe trees from the top of ravines. Sometimes they bring along local forest people adept at climbing trees to collect samples in the upper branches. When the plants flower and fruit the scientists check the plants and the insects and animals they attract.

Today they are so many new species being discovered that the few biologists who can identify rainforest organisms are swamped with new organism given to them by collectors. Wilson said his experience his typical: "Every time I enter a previously unstudied area I find a new species of ant within a day or two, sometimes during the first hour. I search the ground and low vegetation, dig into rotting logs and stumps with a gardeners trowel...On a typical day, the first 40 or 50 colonies encountered might be species already known to science...then a new species. Then another 20 colonies of established species, and one more new species, and so on." [Source “Rainforest Canopy, the High Frontier” by Edward O. Wilson, National Geographic, December 1991]

Studying Birds in the Rainforest

Ornithologists count species by their songs more than by actual sightings. Censuses are taken by catching birds are caught in nets placed in major flyways. When a bird becomes entangled, they generally remain still they are released. In one study in 1987 over 39,000 birds were netted for one study. The birds and animals were counted and sometimes tagged and then released. New species of insect were collected and studied.

Describing what it is like to study birds in the canopy David Anderson of Louisiana State University wrote in Natural History, “I use a crossbow rigged with a fishing reel to fire a “bolt “ (a crossbow arrow) that I have weighted with a lead fishing sinker. The bolt carries the fishing line over a high branch of the tree, and the weight of the sinker brings it back down through the tangle of foliage; I then use the line to draw a parachute cord over the branch, and the parachute cord to pull over the still heavier climbing rope. I tie one end of the rope to another tree, then make my way up the free end using a climbing harness and mechanical ascenders (essentially handholds that slide up but not down ). The whole process is cumbersome, so when it rains I have no choice but to soak it up.”

“Thirty minutes after sunrise I started a three-hour survey. With 10 x 42 Swarovski binoculars in one hand and a mini recorder in the other, I softy narrated the location and behavior of every bird I saw or heard: “Chlorophonia”, upper third of canopy, outer reaches of foliage, mistletoe berry. Tropical gnatcathcer, middle canopy, butterfly larvae in bill.”

Using Automated Radio Telemetry Systems to Study Rainforest Animals

Costa Rica Santa Elena Skywalk Reporting from Barro Colorado Island, Panama, Natalie Angier wrote in the New York Times, “We were tramping doggedly through the forest in pursuit of white-faced capuchins, those familiar organ-grinder monkeys with the wild hair, piercing eyes and impatient scowls of little German professors. Capuchins are said to be exceptionally quick-witted, and that morning they might as well have been swinging from their Phi Beta Kappa keys. [Source: Natalie Angier, New York Times, February 2, 2009]

Capuchins are smart, gorgeous and socially sophisticated, and Dr. Crofoot has relished the many hours spent studying them with the traditional field research tools of binoculars, notebook and a saint’s portion of patience. Yet she and other scientists who work here at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute are thrilled with a new system for tracking their subjects that could help revolutionize the labor-intensive business of field biology.

Called the Automated Radio Telemetry System, the method relies on seven 130-foot-high radio towers scattered across the island that can monitor data from many radio-tagged individuals simultaneously, round the clock, through the calendar. Once an animal has been outfitted with a transmitting device, the towers can track its unique radio signature and, by a process of triangulation, indicate where it is on the island, whether it’s moving or at rest, what other radio-endowed individuals it encounters.

The constant data streams feed into computers at a central lab building on the island, allowing researchers to stay abreast of far more animal sagas than they could possibly follow through direct observation, and to make the best of their hours in the field. If you see an extended flat line on your computer monitor, it’s time to go out, retrieve the corpse and figure out what happened. And because transmitters can now be made as light as two-tenths of a gram, scientists can tag and track katydids, orchid bees, monarch butterflies, even plant seeds.

“Automated systems like this are ushering in a new era of animal tracking,” said Roland Kays, another institute research associate. “There’s a lot of potential for seeing the routes animals take and the decisions they make every step of the way.” The application of radio telemetry towers, global positioning satellites and other cyberscapes to the mapping and deciphering of the natural world has spawned a new subdiscipline. “Movement ecology is the term being thrown around now,” said Dr. Kays, who is also curator of mammals at the New York State Museum in Albany.

Dr. Kays is applying the tracking system to explore the dynamic ménage à trois among the island’s population of ocelots; the ruddy, snouty rodents called agoutis; and the island’s towering and thickly buttressed Dipteryx trees. The agoutis love Dipteryx seeds, and the ones they don’t eat immediately they bury for later consumption. The Dipteryx needs the agoutis to bury its seeds before ground beetles or other animals destroy them, but then the tree wants the rodent to conveniently disappear. Ocelots love agoutis; the rodents are their most important food source. The question Dr. Kays is asking: How many members of each sector are needed to sustain this tripartite economy?

The telemetry system adds to the scientific luster of an island that has been a research mecca ever since Barro Colorado’s 3,865 acres were separated from the mainland by the construction of the Panama Canal in 1914. “It’s a living laboratory,” said Stefan Schnitzer of the University of Wisconsin. “It’s the most heavily studied piece of forest in the world.”

Of course, what sounds dandy in theory can act buggy in practice, and researchers admitted that the upkeep of a complex computerized network in the pitilessly catabolic conditions of a tropical rain forest is always tricky. Moreover, tagging animals remains difficult, particularly when the subjects are smart and easily spooked, as capuchins are.

Measuring Trees in the Congo

canopy profile Describing their work measuring trees in undisturbed forests to calculate CO2 absorption by these forests, Simon Lewis, Aida Cuní Sanchez and Wannes Hubau wrote in The Conversation: Tracking trees in tropical forests is challenging, particularly in equatorial Africa, home to the second largest expanse of tropical forest in the world. As we want to monitor forests that are not logged or affected by fire, we need to travel down the last road, to the last village, and last path, before we even start our measurements. [Source: Simon Lewis, Professor of Global Change Science at University of Leeds and, UCL, Aida Cuní Sanchez, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of York, and Wannes Hubau, Research Scientist, Royal Museum for Central Africa, The Conversation, March 6, 2020]

“First we need partnerships with local experts who know the trees and often have older measurements that we can build upon. Then we need permits from governments, plus agreements with local villagers to enter their forests, and their help as guides. Measuring trees, even in the most remote location, is a team task. “The work can be arduous. We have spent a week in a dugout canoe to reach the plots in Salonga National Park in central Democratic Republic of the Congo, carried everything for a month-long expedition through swamps to reach plots in Nouabalé Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo, and ventured into Liberia’s last forests once the civil war ended. We’ve dodged elephants, gorillas and large snakes, caught scary tropical diseases like Congo red fever and narrowly missed an Ebola outbreak.

“Days start early to make the most of a day in the field. Up at first light, out of your tent, get the coffee on the open fire. Then after a walk to the plot, we use aluminum nails that don’t hurt the trees to label them with unique numbers, paint to mark exactly where we measure a tree so we can find it next time, and a portable ladder to get above the buttresses of the big trees. Plus a tape measure to get the tree diameters and a laser to zap tree heights.

“After sometimes a week of travel, it takes four to five days for a team of five people to measure all 400 to 600 trees above 10 cm diameter in the average hectare of forest (100 metres x 100 metres). For our study, this was done for 565 different patches of forest grouped in two large research networks of forest observations, the African Tropical Rainforest Observatory Network and the Amazon Rainforest Inventory Network.

“This work means months away. For many years, each of us has spent several months a year in the field writing down diameter measurements on special waterproof water. In total we tracked more than 300,000 trees and made more than 1 million diameter measurements in 17 countries.

“Managing the data is a major task. It all goes into a website we designed at the University of Leeds, ForestPlots.net, which allows standardisation, whether the measurements come from Cameroon or Colombia. Many months of detailed analysis and checking of the data followed, as did time for a careful write-up our findings. We needed to focus on the detail of individual trees and plots, while not losing sight of the big picture. It’s a hard balancing act.

Rainforest Fragment Studies

Scientists have studied isolated fragments of Amazon rainforest intentionally left behind in areas cleared for ranching and agriculture to see how large an area is necessary to maintain a healthy population of species. Located about 80 miles south of Manaus, Brazil, the land was cleared into five 1-hectare (about 2.5 acres), five 10-hectare, one 100-hectare, one 1000-hectare and one 10,000-hectare plots of forest. [Source: Edward O. Wilson, National Geographic, December 1991; Jake Page, Smithsonian magazine, April 1988]

The project began in 1976 and was expected to run until 1999. Baited traps were checked every few days to see how rodents and marsupials are getting on. The one-hectare island of rainforest usually becomes filled with birds after the forest around it has been cleared because the birds that lived in the cleared forest needed somewhere to go. When the food supply of island was depleted six months later the birds too were gone.

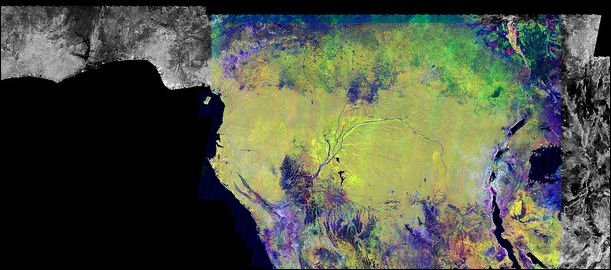

Satellite view of the Congo basin

In the 10-hectare plots certain species of birds left after the colonies of army ants flushed out crickets, grasshoppers and cockroaches the birds ate. Frog species also disappeared because the peccaries that rutted out the water holes they lived in also disappeared.

The one-and ten-hectare plots become completely edge in a few months. Scientist estimate that a patch of virgin rainforest needs a buffer zone at least a few hundred meters wide to make the sure the edge effect doesn't creep into the virgin forest.

New species moved into the disturbed areas. According to one study, small mammals were more abundant in the disturbed fragments than in the rainforest.

Satellites and Remote Sensing of the World’s Rainforests

Remote sensing devices mounted on high-flying planes and satellites have been used to monitor the rainforest. In some cases land-based scientists check the images against what they observe on the ground and use the data help calibrate instruments, interpret the images and make sure analysis of the images is accurate. To get the most accurate data available harvesters of chicle (the chewy ingredient in gum) have been hired to climb up 100 foot trees and mount devices in the canopy.

Remote sensing devices used to monitor the rainforest include: 1) the Landsat satellite which reads surface temperature and reflected sun light with infra-red photography and is useful in measuring amounts of vegetation, which gives off heat especially at night and shows up red; 2) radar imagery taken from planes at 30,000 feet that can pick up crops growing under trees and fallen logs (an indication of cleared land); and 3) .satellite-based imaging spectrometer that measures vegetation density by monitoring 224 bands on the electromagnetic spectrum (compared to seven on the Landsat) and can determine the chemical composition of different materials

The Thermal Scanner , a sensitive satellite-based devise, can distinguish between crops, recently felled trees, savannah and bare fields (areas that look similar on the Landsat photographs) and portray the landscapes in different colors with cleared land appearing deep blue; upland rainforest, light blue; and swamps, yellow.

Used together these devises can determine plant type and check the effects of environmental changes. Much of the data collected is raw and very complex and it will scientist a while to figure out exactly how to read it. Each remote sensing devise has its draw backs. The radar imagery for example can not tell the difference between a freshly plowed field and one sprouting corn.

Southeast Asia fires in October 2006

Google Unveils Satellite Platform to Aid Forest-Saving Efforts

Reuters reported in 2010, Google has “unveiled technology it says will help build trust between rich and poor countries on projects designed to protect the world’s tropical forests. Measuring the success of forest-protection plans in places like the Amazon, Indonesia and the Congo basin has always been difficult because tree disease, corruption, and illegal logging threaten vast remote areas that scientists can’t monitor by land. [Source: Reuters, December 2, 2010]

The platform, called Google Earth Engine, takes vast amounts of forest images from U.S. and French satellites and crunches it at shared data centres, through cloud computing. It allows scientists to monitor forests from their own computers in minutes or seconds instead of the hours or days it took before. Google also wants to eventually sell access to advanced aspects of the tool to carbon traders, policy makers, and researchers working in forestry.

In conjunction with Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) programs Google UK has released satellite images of rainforest areas on the Internet, allowing anyone with Internet access to compare images of the same places at different times to monitor deforestation and make sure countries involved with the REDD agreement and keeping their promises. Philipp Schidler of Google UK told the Times of London, “Our engineers are exploring how we might contribute to this effort by developing a global forest platform that would enable anyone in the world, including tropical nations to monitor deforestation and draw attention to it.”

Famous Rainforest Scientists

Edward O. Wilson is one of the world most famous biologist and rainforest advocates. A native of Alabama and a professor at Harvard, he has written 22 books, including a Pulitzer Prize-wining encyclopedia on ants, and nearly 400 scholarly articles.

Al Gentry, curator of the Missouri Botanical Garden, has often been described as the man who can identify more tropical plants than anyone else in the world. He has spent a lot of time in rainforests looking for plants and often follows loggers to find new species. As of the late 1990s he had been jailed 15 times for gathering plants in unauthorized areas.

Dr. Marc Plotkin, the author of “Tales of the Shaman's Apprentice” and “Medicine Quest: In Search of Nature's Hidden Cure”, is a major advocate for the belief that miracle medicines and marketable goods can be found in the rainforest. Plotkin's Amazon Conservation Team is supported by actress Susan Sarandon and Todd Oldham. See Rainforest Products and Medicines.

tropical wet forests

An ecological SWAT team known as the Rapid Assessment Program (RAP) has been set up by the Washington D.C.-based Conservation International to develop a strategy for saving the rainforest by focusing first on the most threatened rainforests.

The members of RAP list like of Hall of Fame or rainforest scientists. The so called "Bio-squad" included Gentry; Ted Park, a Louisiana State University ornithologist, who can identify most if the New World tropical birds by their songs alone; Louise Emmons, a Smithsonian research associate who wrote the definite pieces on the 18 species of rainforest rat; and Robin Foster, an ecologist for the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, who is an expert at drawing information about rainforests from satellite and aircraft imagery.

Living, Working and Surviving in the Rainforest

Working in the rainforest sometimes comes with high costs. Emmons caught the bubonic plague in Bolivia; Foster has lost two thirds of his liver to various tropical diseases; and Gentry survived being bitten by a pit viper even though he was four hours from the nearest town.

Some of the worst accidents occur when scientists get hit by sudden powerful storm while they are up in the canopy. Scientists working in the rainy season sometimes quickly ascend take a few samples, clip a few leaves and then quickly descend to avoid trouble. Relieving oneself or not reliving oneself can present challenge to scientists who spend all day in the treetops in a harness.

The nemesis of all rainforest scientists are termites, stinging wasps and ants. Ants climb into computers and termites eat away the legs of tables and beds. One botanist who suddenly came face to face with a wasp nest in the canopy tried to escape by kicking the tree. His rope snapped and he plummeted 75 feet, crash landing on a root buttress after his wall was broken branches and leaves. Undeterred, he was back in the tree tops that same day.╜

Simply getting to the study sites can be a problem. A smooth logging road can turn to ankle-deep mud after one rainstorm. Thick, wet clay can make boots feel like their full of lead and suck shoes off of feet and clamp on to vehicles like a crocodile clamping gown on a leg. .

The U.S. Air Force runs a Tropical Survival School in the jungles of Panama to teach pilots how to survive if their planes is shot down in a tropical rainforest. Trainees learn to find edible and medicinal plants, extract water from jungle vines, make a fishing net and a hammock with a parachutes, attract fish with termites, and make huts from palm fronds. One of the most important plants students about learn is the "tinder bush," so named because it contains so much resin that "you can light a fire from it with a single match in a driving rain."

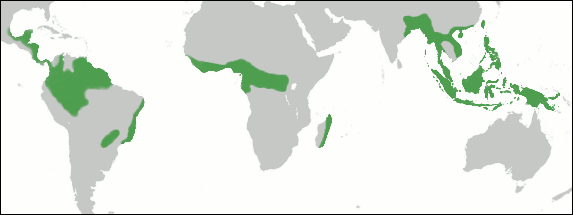

Cloud forest world distribution

“Cabruca” refers to a way of cultivating wild cacao (chocolate) trees in the forest by thinning out the understory — trunks, dwarf palms, vines — and planting in clear spaces under the protective canopy. It is a way of farming in the rainforest that keeps the rainforest essentially intact.

Climbing the World's Tallest Tropical Tree

tree buttress The world's tallest known tropical tree — the "Menara" tree in a rainforest in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo — measures an astounding 100.8 meters (330 feet) from ground to its tippy top — making it higher than a football field is long. [Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, April 6, 2019]

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science:The team came across Menara by using laser technology known as light detection and ranging, or lidar. In essence, an aircraft carrying a lidar device flew overhead as laser pulses were shot down and then reflected back when they hit the forest canopy and ground, providing data for a topological map.

After reviewing the data, the researchers trekked out to see Menara in August 2018. There, they scanned the tree with a terrestrial laser to create high-resolution 3D images, and they also snapped images from above with a drone. A local climber, Unding Jami, of the Southeast Asia Rainforest Research Partnership, scaled the tree in January 2019 to measure its exact height with a tape measure. "It was a scary climb, so windy, because the nearest trees are very distant," Jami said in a statement. "But honestly, the view from the top was incredible. I don't know what to say other than it was very, very, very amazing!"

Jami's feat reveals that Menara is likely the tallest flowering plant in the world, as it's taller than the previous record holder; a eucalyptus tree (Eucalyptus regnans) in Tasmania that's 326 feet (99.6 meters) tall.

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com ; Wikicommons

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2024