TREES IN JAPAN

Trees are distributed in the following five zones, all of which lie in the East Asian temperate zone: (1) the subtropical zone, including the Ryukyu and Ogasawara islands groups; (2) the warm-temperature zone of broad-leaved evergreen forests, which covers the greater part of southern Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu; characteristic trees are “shii “and “kashi”, both a type of oak; (3) the cooltemperature zone of broad-leaved deciduous forests, which covers central and northern Honshu and the southeastern part of Hokkaido; Japanese beech and other common varieties of trees are found here; (4) the subalpine zone, which includes central and northern Hokkaido; characteristic plants are the Sakhalan fir and Yesso spruce; (5) the alpine zone in the highlands of central Honshu and the central portion of Hokkaido; characteristic plants are alpine plants, such as “komakusa “(“Dicentra peregrina”). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Trees are distributed in the following five zones, all of which lie in the East Asian temperate zone: (1) the subtropical zone, including the Ryukyu and Ogasawara islands groups; (2) the warm-temperature zone of broad-leaved evergreen forests, which covers the greater part of southern Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu; characteristic trees are “shii “and “kashi”, both a type of oak; (3) the cooltemperature zone of broad-leaved deciduous forests, which covers central and northern Honshu and the southeastern part of Hokkaido; Japanese beech and other common varieties of trees are found here; (4) the subalpine zone, which includes central and northern Hokkaido; characteristic plants are the Sakhalan fir and Yesso spruce; (5) the alpine zone in the highlands of central Honshu and the central portion of Hokkaido; characteristic plants are alpine plants, such as “komakusa “(“Dicentra peregrina”). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Matsu “and “sugi”, Japanese pine and cedar, respectively, are common throughout the Japanese archipelago — even in warm southern regions — and are very familiar to the Japanese people. Pines often make splendid scenery. The most notable scenic spot is Amanohashidate, in Kyoto Prefecture, with more than 6,000 pine trees forming lines on the sandbar. Large pine trees, which grow to a maximum height of about 40 meters, also serve as a windbreak in coastal areas. Small pines are used as “bonsai”, garden trees, and materials for houses and furniture. Pines are also considered to be holy trees.

“People in the olden days were awed by nature and saw in plants and trees symbols of divine spirits. At one time, for example, it was common to worship evergreen trees such as pine, cedar, and cypress because they were thought to provide habitation to heaven-sent deities. The still-common practice of decorating the entrance-ways of houses at New Year’s with pine branches — “kadomatsu”, literally “gate pine” — comes from the belief that this was an appropriate way to welcome the gods.

Perhaps the most famous tree in Japan is the Jomon cedar on Yakushima Island south of Kyushu. It has a 28-meter circumference and may be 7,200 year old, making it possibly the oldest living thing on the planet.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PLANTS IN JAPAN: FLOWERS, ORCHIDS, MARIMO BALLS, KUDZU, BAMBOO factsanddetails.com

TIMBER, LUMBER AND FORESTRY JAPAN factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE HABITATS: FORESTS, SATOYAMA AND RICE PADDY ECOSYSTEMS factsanddetails.com

Types of Trees in Japan

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Botanists understand and document plant diversity using a formal taxonomic system. Trees are first divided into two major groups, gymnosperms and angiosperms, based on the type of flower and fruit. Gymnosperms include all the trees we normally call conifers, and angiosperms the ones we think of as broad-leaves. Some trees, such as the gin kilograms o, however, have wide leaves but are actually gymnosperms. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, February 28, 2013]

“The vast majority of Japan’s native tree species are broad-leaves, and most of the nation’s natural forests are dominated by broad-leaves. The general idea is that angiosperms, which sport a more advanced flower structure, enjoy a competitive advantage over gymnosperms. All else being equal, angiosperms will thus tend to monopolize favorable environments, leaving the gymnosperms to get by in marginal habitats such as deeply shaded valleys and exposed ridges.

“But today, as anyone traveling around Japan can verify at a glance, the hills and lower mountainsides in most areas of the country are totally dominated by conifers. In fact, a full 40 percent of the nation’s forests are pure stands of conifers. These are not natural forests at all, but commercial timber plantations.

Red pine forest in the Kyoto area are being devastated by a disease called pine wilt caused by a half-millimeter-long worm. To battle the pest, resilient trees are being grafted onto those who are more susceptible to it.

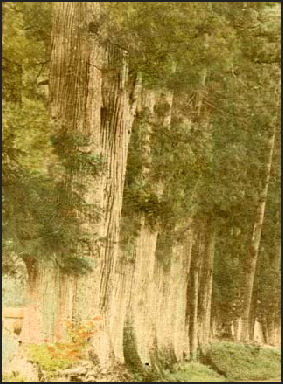

Sugi (Japanese Cedars Cryptomeria)

Sugi (Cryptomeria cedars) redwoods and giant sequoias of California. Although not quite as tall and fat as the California trees large specimens can live for over 1,000 years, and reach heights of up to 50 meters and are known for growing straight and true. Redwoods and sugi are related to similar trees found 150 million years ago in the Jurassic Period. Sugi trunks are covered with a brownish, red bark that peels off in vertical strips. Trunks can attain a diameter of two meters or more. The Japanese name sugi is thought to be derived from massugu-ki, or "perfectly straight tree." Sugi are often found at Shinto shrines (See Religion and Architecture) [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, February 28, 2013]

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: ““Sugi is what botanists call a monoecious species. This means that the male and female flowers bloom separately, but each individual tree has both types. The light brown conelike male flowers occur in clusters at the tips of some branches. When daytime temperatures begin climbing up into the mid-teens, these cones split open to release their loads of miniscule feather-light pollen grains. The inconspicuous female flowers form at the tips of separate branches. When pollinated these structures develop into spiky cones that ripen and release their seeds in late autumn and early winter. The sugi flowers rely solely on the wind to carry their pollen from tree to tree. The pollen grains are produced in mind-boggling quantities, and are able to float for dozens or even hundreds of kilometers on the spring breezes. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, February 28, 2013]

Mythological Origins of Sugi Trees

Kevin Short wrote in the Japan News: “According to Japan’s classic mythology, sugi trees were created by the kami deity Susanoo, the younger brother of Amaterasu the Sun Goddess. Susanoo is one of the most enigmatic characters in the myths. From birth he was a problem child, crying and carrying on in all sorts of manners. His father, the male creator kami Izanagi, banished him to the underworld. [Source: Kevin Short, Japan News, March 21, 2017]

“Before heading down, Susanoo wanted to say goodbye to his older sister in Takama-ga-Hara, the Celestial Realm. Here again he behaved in a truly outrageous manner, scattering feces in the banquet hall during the Festival of the First Fruits, and perhaps even more serious, breaking down the aze dikes and filling in the irrigation ditches among the celestial rice paddies.

“So gross was her brother’s behavior that Amaterasu simply freaked out, hiding herself in a cave and plunging the world into darkness. Eventually she was enticed back out, and Susanoo was summarily deported from the Celestial Realm. He landed first on the Korean Peninsula but soon crossed over to the Izumo area along the Sea of Japan.

“Back on Earth, Susanoo seems to have undergone a complete change of personality. He is credited with slaying a nasty eight-headed dragon, and with introducing various edible and useful plants. The first sugi are said to have grown from hairs that he plucked from his beard and scattered across the countryside.

“Susanoo went on to become a founding hero in Izumo mythology and sugi trees, once relegated to marginal habitats, were planted widely throughout the land. Sugi plantations have thus been a part of the Japanese landscape for thousands of years.

Japanese Cedars and Allergies

About one in 10 Japanese (13 million people) suffer from cedar hay fever whose season sometimes lasts from February to late May. You can tell its cedar hay fever season by the number of people wearing surgical masks and eye protection.

The presence of cedar pollen depends on the growth of cedar bud the previous summer with high temperatures and low rainfall producing the most pollen. Particularly after a dry, hot summer huge clouds of cedar pollen fill the air, which causes an allergic reaction. In late February and March, when the pollen concentrations are at their highest, the pollen count is flashed on billboards in Tokyo and shown on television weather reports. Allergy hot lines receive thousands of calls.

"At the peak, you can actually see pollen fog coming from the cedar forests," a Tokyo allergy specialist told the New York Times. "It is so bad that when people first began to notice this a decade or so ago they thought they were forest fires."

The allergies are the result of too many cedar trees. One sufferer told the New York Times: "When I started suffering I wanted to scratch out my eyes. I finally realized that this was the result of the government's misguided reforestation policy." In some places old cedar trees are being cut down and replaced with species of cedar that produce less pollen,

In some places cedar trees, cypresses and other evergreens are being cut down and being replaced with broad-leaved trees to reduce allergy-inducing pollen and bear attacks.

Pollen-Free Cedars

In November 2012, The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “In a development likely to be good news for hay fever sufferers, saplings of a new no-pollen cedar tree have been planted in Toyama Prefecture, where technology for their mass production from seeds was first realized domestically. It is the forest industry's first full-scale plantation of pollen-free cedar trees for uses such as timber for housing, according to the prefecture's Forestry Research Institute. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 13, 2012]

In 1992, a pollen-free, domestic cedar tree was discovered at a shrine in the prefecture, prompting the institute to conduct research. The institute began interbreeding the tree with other species, and in 2008, a cedar tree producing no pollen was created. Since 2009, the institute has been promoting mass production of the tree's saplings. The planting of the pollen-free saplings started in a mountain forest in the town of Tateyama on Saturday. The town's forestry association officials planted about 300 saplings from 30 to 60 centimeters tall in about 1,500 square meters of cleared forest land.

The Toyama prefectural government plans to distribute the saplings to four forestry associations and others in the prefecture within this fiscal year, and to plant 4,700 saplings in about 23,000 square meters of forests and mountains. After 2016, it plans to ship the saplings to other prefectures.

Hinoki

Hinoki is a conifer sometimes called hinoki cypress in English that is native to Japan and Taiwan. Hinoki trees stand tall and straight and have reddish brown bark and produce a hard wood that has been a favorite of craftsmen, home builders and furniture makes since ancient time because it has a nice smell and is resistant to rot. According to legend the first hinoki trees came from the chest hairs of a powerful deity . Some of the oldest wooden buildings in Japan and the world and sacred shrines dedicated to the Sun Goddess in Ise are made with it. Japanese have long used it make bath tubs and kitchen items because is resistant to mildew and has antibacterial qualities.

Hinoki is the second largest plantation tree after cryptomeria. Japanese foresters tend to grow cryptomeria along valley bottoms and hinoki higher up the slopes. Cryptomeria grows faster than hinoki, It is usually ready for harvest after 50 years compared to 75 to 80 for hinoki but the wood is softer and not quite so valuable.

Chestnuts in Japan

The fungus blight disease that almost completely wiped out American chestnut tree in the early 20th century is thought to have arrived in the United States on introduced Japanese chestnut trees (C. crenata), and provides a classic example of a pathogen jumping host species then spreading like wildfire. The Japanese trees do contract the disease, but over the long millennia have developed a partial immunity. Infected trees sicken but eventually recover. The American chestnuts, on the other hand, lacked all resistance to the disease, and quickly succumbed. A similar introduced fungus has devastated elm trees throughout Europe and North America. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, October 5, 2011]

Chestnuts were one of the very first plants to be actively cultivated in Japan. Excavation work at the spectacular Sannai-Maruyama archeological site in Aomori Prefecture has revealed a large prehistoric village that thrived nearly 7000 years ago. The Jomon inhabitants utilized a wide variety of forest and marine resources, but the staple of their diet was cultivated chestnuts, grown in extensive orchards. Huge chestnut logs were also used as columns for building homes and ceremonial centers. One impressive structure is supported by six chestnut columns, each a full meter in diameter, and is thought to have stood three stories high.

In the Kanto region, chestnuts can currently be found both cultivated in commercial orchards and growing wild in native deciduous woods. The spiny urchins (iga in Japanese) of the wild forms are only half the size of the cultivated ones, but the hard nuts inside are just as tasty

Acorns and Japan

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Japanese kids love acorns. There are songs about them and toys made from them. Collecting them is popular past time. Acorns (donguri) are the fruits of oak and chinkapin trees. They consist of a hard-shelled nut resting in a scaled bowl-like receptacle known as a cupule, called kakuto in formal botanical Japanese, but usually referred to as either boshi (hat) or hakama (skirt). The form of the cupule and the pattern of the scales, rather than the shape of the nut itself, are important clues for determining which tree an acorn comes from. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, November 8, 2012]

Japan is home to about 20 native acorn-producing trees, both deciduous and evergreen. Based on cupule form and scale pattern, acorns can be divided into four groups. 1) Scales overlap to form horizontal lines--Characteristic of a group of evergreen oaks, comprising eight native species, known collectively as kashi. 2) Densely packed tiny scales overlap like miniature roof tiles--characteristic of a group of deciduous oaks, comprising four deciduous species including the ubiquitous konara (Quercus serrata); as well as one live oak and two species of stone oak (Lithocarpus; matebashi in Japanese). 3) Scales stick out like burrs--Characteristic of a group of deciduous oaks with three species, including the well-known kunugi (Q. acutissima) and kashiwa (Q. dentata). 4) Cupule shaped like a sheath that splits open--Characteristic of three species of evergreen chinkapin (Castanopsis), collectively known as shii (as in shii-take mushrooms). The sudajii (C. sieboldii) is the most common chinkapin in the Kanto area.

Acorns are rich in nutrients, and form a major element in the diet of animals such as Japanese squirrel, tanuki raccoon dog, Asiatic black bear, shika deer, wild boar and Japanese macaque, as well as birds such as the jay (kakesu). During the Jomon period, which lasted from 14,000 to 3,000 years ago, the local people depended heavily on acorns. Be careful though: The acorns of most Japanese oaks contain tannins and other bitter chemicals, and must be thoroughly leached before eating. Only the chinkapin and stone oak acorns can be roasted and eaten as is.

Forest Trees, Flowers and Plants in Japan

Japanese deciduous forests are dominated by oak and hornbeam, but include a rich assortment of dogwood, cherry, snowbell (egonoki), magnolia (kobushi), chestnut, hackberry (enoki) and zelkova (keyaki). A whole group of perennial wildflowers, including various species of orchid, lily, gentian, violet and anemone, will grow nowhere else but on the floor of these forests. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, May 5, 2011]

The Japanese fawn-lily is a very popular plant here in Japan. Short wrote: “The petals and sepals are a soft pink with deeper purple markings, and when fully open fold back nearly 180 degrees, eventually pointing toward the rear of the flower. Emerging from the center is a single long pistil, with a three-headed stigma, and six deep indigo stamens. The leaves of this genus are often dappled, like the skin on a baby deer, giving rise to the common English name of fawn-lily. A starchy flour made from the underground parts of the plant, called katakuri-ko, is used in manufacture of the best quality Japanese sweets.

Oak trees in Japan are being ravaged by pathogenic fungus transmitted by the ambrosia beetle. The loss of oaks lessens the water retention capacity of forest soils and deprives bears, wild boars and other wild animals of acorns, an important food source for them. The fungus destroys the tree’s ability to pumps water up from its roots to its leaves.

The keyaki, or Japanese zelkova tree (Zelkova serrata), is a member of the elm family. Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Rivaling the cherry tree in terms of sheer familiarity, it has distinctive shape like an upturned broom and is found in native deciduous woodlands as sell as parks and gardens. The keyaki's tall but narrow growth form also makes them especially suitable as urban street trees. Almost any Japanese can recognize keyaki by their shape.” [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, April 21, 2011]

“The female flower of the keyaki, if properly pollinated, will develop into a small, hard nutlet. Come autumn, when the nutlets have ripened, the entire twig will drop off the tree, with the small leaves, now dry and brittle, still attached. By themselves the nutlets would all fall directly beneath the parent tree, but the attached leaves work like parachutes and sails, carrying the entire twig far and wide on the wind.

Japanese Dogwoods and the Story Behind Its Red Branches

Dogwoods — known in Japanese as mizuki, which literally means water (mizu) tree (ki or gi), grows wild in woodlands throughout Japan, and is also widely planted in parks and schoolyards. The Japanese mizuki prefers thick, moist soils, but derives its name from the copious liquid sap that fills the trunk and branches. In early summer, densely packed clusters of tiny white flowers, each with four petals and four stamens, bloom at the tip of the branches. These later ripen into purple and red fruits, which are favorites of many species of bird. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, October 7, 2010]

The common English name dogwood is thought to have originated as dagwood, a dag referring to a thin, sharply pointed instrument such as a meat skewer. These trees produce a hard, heavy wood which is ideal for manufacturing small objects such as skewers and tool handles. Here in Japan, the mizuki is used to carve wooden geta clogs, traditional toys such as koma spinning tops and kokeshi dolls, and also as skewers for delicious dango deserts made from sticky rice and sweetened bean paste.

The branched stalk that holds first the mizuki's flowers and later the fruits is a deep pinkish red. A story that explains why this is so goes: One autumn, some matagi [traditional hunters] out bear hunting were caught in a sudden storm and were forced to spend the night in a small hut. Late that night, a young woman, her stomach incredibly swollen and clearly about to give birth, knocked on the door and asked them to give her shelter for the night.

This caused the hunters great concern. Like all traditional Japanese mountain folk, the matagi pay great heed to the local yama-no-kami, or mountain spirit. It is only with the blessings of this spirit, they believe, that they enjoy the privilege of walking safely in the mountains and harvesting certain plants and animals. The mountain spirit, however, is a goddess, and expects men to be true to her in heart and mind while working in her domain. Even dreaming of a woman is enough to send a traditional hunter scurrying back down to his village.

Because of this, the matagi were naturally reluctant to let the woman into their hut. On the other hand, they could see that she was in deep trouble. Eventually their natural generosity won out, and they let the woman in, laying down a cushion of dogwood boughs for her to rest on.

During the night, the woman gave birth, and in the morning left with a healthy baby boy. As she left she recited for the matagi a list of times and places where they could be sure that bears would be waiting for them. She was, it turned out, the mountain spirit herself. Later, when the matagi cleaned up the hut, they found that the mizuki's flower stalks, originally white, had all been stained red by the mountain spirit's blood.

Image Sources: 1) Jun of Goods from Japan 2) 4) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 3) 5) 7) Ray Kinnane 6) Neil Ducket, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, Daily Yomiuri, Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025