RADIOACTIVE SLUDGE, WASTE AND DEBRIS FROM THE FUKUSHIMA DISASTER

radioactive waste The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Radioactive materials have been found in sludge at numerous water purification plants and sewage treatment facilities in a wide area of eastern Japan, creating a serious headache for local governments. Sludge is residue left at these facilities after water is purified or treated. The material most commonly detected in the sludge has been radioactive cesium. The amounts of radiation are relatively low and pose no health risks if the sludge is disposed of properly. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 17, 2011]

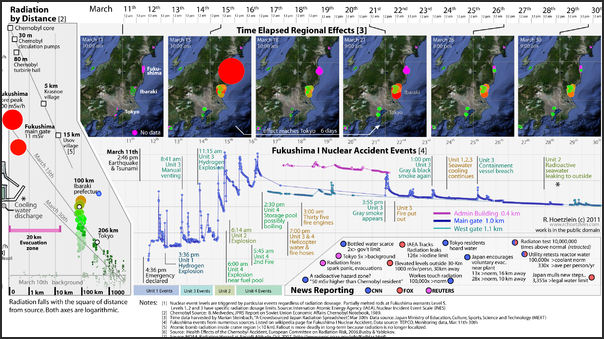

Radioactive materials entered the air as the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant in Fukushima Prefecture was hit by a spate of accidents, including hydrogen explosions, as a result of the March 11 earthquake and tsunami. The materials then mixed with rain, fell to the ground, and accumulated at the facilities, likely through storm sewers and other means. As an immediate measure, the government has instructed the facilities to store sludge containing radioactive cesium on their premises. However the amount of stored waste has continued to increase, causing fear that facilities in Tokyo, as well as Kanagawa, Saitama and Ibaraki prefectures may be filled with bags of sludge later this month.

In the early days after the earthquake, some Japanese officials privately feared an even more damaging scenario that could have rendered half of this island nation uninhabitable. “Spine-chilling,” former prime minister Naoto Kan said after leaving office, reflecting on the possibility.

Getting rid of the radioactive debris proved to be a problem for Fukushima Prefecture . There is a lack of storage space and incinerators to dispose of it and sharp disagreements over where it should ultimately be disposed of. According to an article in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “The Environment Ministry plans to finish disposing of the debris by the end of March 2014, but local governments believe this target will be impossible to meet.” [Source: Akihiro Kitaide and Tsuyoshi Sakuragi, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 27, 2011]

“The city of Soma, Fukushima Prefecture, has to dispose of 470,000 tons of debris dumped by the March 11 tsunami,” wrote Akihiro Kitaide and Tsuyoshi Sakuragiin the Yomiuri Shimbun. “A temporary storage site set up at an industrial complex in the city emits a foul odor that is a mixture of seawater and debris including chunks of wood, soil, sand, fishing nets, guard rails, bicycles, chests of drawers and dolls. Companies operating at the complex have complained about the stench.” "Insects are flying all around, dust gets blown up and the smell is awful," an official at one company said.

“The ministry estimates the March 11 tsunami dumped 2.88 million tons of debris in Fukushima Prefecture, mostly in coastal areas such as Soma that were hit hard by the tsunami. Only about 20 percent of the debris has been removed, but 134 temporary storage sites--with a total area of 100 hectares--are already nearly full. On June 19, an expert panel of the Environment Ministry concluded that incinerated debris ash can be buried in sites, except in the no-entry zone around the nuclear plant, if it contains less than 8,000 becquerels of radioactive materials per kilogram....However, incineration facilities themselves are in short supply. The 19 such facilities in coastal areas burned 537,600 tons of waste in fiscal 2009--equivalent to less than 20 percent of the debris littering the prefecture.”

Links to Articles in this Website About the 2011 Tsunami and Earthquake factsanddetails.com : MARCH 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI IN JAPAN: DEATH TOLL AND ITS BEGINNING factsanddetails.com ; ARTICLES ABOUT THE CRISIS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DAMAGE FROM 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND SURVIVOR STORIES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT DISASTER AFTER THE MARCH 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI factsanddetails.com ; MELTDOWNS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HOURS OF THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com ; TEPCO AND THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT DISASTER: SHODDY SAFETY MEASURES, THE YAKUZA AND POOR MANAGEMENT factsanddetails.com ; JAPANESE GOVERNMENT'S HANDLING OF THE TSUNAMI AND THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com ; BRAVE WORKERS AND ROBOTS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT factsanddetails.com ; RADIOACTIVE WATER CONTAINMENT AT FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT factsanddetails.com COLD SHUTDOWN AND LONGER TERM MANAGEMENT OF FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR CRISIS factsanddetails.com ; RADIATION RELEASES, FEARS AND HEALTH CONSEQUENCES OF THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com

Storing Radioactive Sludge, Dirt and Ash

radioactive waste dump In July 2011, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported, “At least 120,000 tons of sludge and ash either confirmed or suspected to have been contaminated by radiation from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant has been put into storage at water treatment and sewage plants in Tokyo and 13 eastern prefectures. Municipalities concerned have called on the central government to find locations where the contaminated sludge and ash can be treated or safely disposed of. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun. July 30, 2011]

Under guidelines for handling radiation-contaminated material announced by the central government on June 16: 1) Material contaminated with radioactive cesium of more than 100,000 becquerels per kilogram should be stored in shielded facilities. 2) Material with cesium levels of 8,000 to 100,000 becquerels per kilogram should be sent to plants designed to handle treatment of industrial waste. 3) Material with cesium levels below 8,000 becquerels per kilogram can be buried.

Water treatment facilities in 11 of the 14 prefectures — Tokyo and Nagano and Shizuoka prefectures being the exceptions — have found a total of about 37,290 tons of stored dehydrated sludge to be radioactive, according to the ministry. About 54,630 additional tons of stored sludge and ash have yet to be tested for radiation.

None of the sludge was found to have radiation levels exceeding 100,000 becquerels per kilogram, but 1,557 tons of mud with cesium levels of between 8,000 and 100,000 becquerels per kilogram remained untreated in five prefectures, including Fukushima, Miyagi and Niigata. Radiation in the remaining sludge was below 8,000 becquerels per kilogram.

The municipalities concerned have been unable to find anywhere to dispose of the sludge, or treat it so it can be safely reused. Some facilities said their storage spaces would be filled with sludge and ash within a few months. The government and the ruling Democratic Party of Japan are working on a lawmaker-sponsored bill for a law that will allow the state to take the initiative in treating radioactive sludge and other contaminated materials, according to sources.

Cleaning Up Radiation

In October 2011, Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda, said the government would spend at least $13 billion to clean up vast areas contaminated by radiation. In an interview with the public broadcaster NHK, Mr. Noda said the decontamination was “a prerequisite for people to return to their homelands.” At that time the government had raised $2.9 billion for the decontamination, Mr. Noda said, and plans to allocate a further $3.3 billion in the third extra budget. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com Reuters, October 21, 2011]

remote-controlled robo crawler dumper Radiation clean ups included using street sweeping vehicles and high-powered sprayers and men with brushes to clean sidewalks and roads along routes to and from primary schools. Top soil and weeds were removed in many places. Homeowners in Fukushima Prefecture frequently mopped their floors and sprayed the outsides of their house with high-pressure hoses. Fukushima city said its plans to decontaminate the entire city.

One survey found that radiation levels on the roof, gutters and walls sprayed with high-pressure cleaners and water decreased to 3.0 microsieverts per hour from 13.5 microsieverts per hour."It's easy to use a high-pressure cleaner," a member of the painting association said. "A cheap one for home use costs about 20,000 yen to 30,000 yen." But the member also warned: "Cleaning a roof is dangerous because it's slippery. It's better to ask experts to do it." A 42-year-old man who lives in a house cleaned with these methods said, "I'm relieved if the radiation level decreases even a little." [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 30, 2011]

Radiation Decontamination

Japan must decontaminate an area around the plant of some 930 square miles, according to the Environment Ministry. That process could clear the way for some evacuees to return home, if they are willing to take the risk. Many areas within the no-entry zone — a 12-mile radius around the plant — will be uninhabitable for decades, maybe longer. [Source: Chico Harlan, Washington Post, December 16, 2011]

Tetsu Joko wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Full-scale decontamination operations have started in some areas of Fukushima and Date. Removing surface soil has shown good results, but municipalities are having difficulty finding temporary storage sites to keep contaminated soil until intermediate storage facilities become available. As high-pressure hoses do not remove radioactive substances on uneven roads and roof tiles, municipalities will need to come up with more effective decontamination methods. Everybody wants to restore safe living environments as soon as possible, but some people are concerned the decontamination operations might actually spread radioactive substances. Hiroaki Koide, assistant professor at Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute, said, "I think children and pregnant women, who are more susceptible to the negative effects of radiation, should be evacuated to safer places while decontamination work is carried out." [Source:Tetsu Joko, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 2012]

According to a Washington Post article and Mainichi Shimbun report Japan is discussing a plan to categorize the off-limits areas more precisely. In areas exposed to fewer than 20 millisieverts of radiation per year, the Japanese upper limit for citizen exposure, residents can make “preparations” to soon return. In areas exposed to between 20 and 50 millisieverts annually, residents will need to wait at least several years before returning. Areas exposed to more than 50 millisieverts annually will be labeled “difficult to return” zones, off-limits for decades.

remote-controlled robo Bobcat The municipal government of Minami-soma in Fukushima Prefecture plans to finish decontaminating 307 square kilometers of the land in the city, excluding the no-entry zone, as early as fiscal 2014. However, as of late September 2011 decontamination had been completed at only about 30 facilities, including schools, out of a total of an intended 237. Decontamination on private houses had yet to begin. So far, the municipal government remains undecided on temporary storage sites for the contaminated soil. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 2, 2011]

According the central government's plan, it will decontaminate areas where yearly radiation doses in soil exceed 20 millisieverts. Municipal governments are required to decontaminate areas with yearly radiation doses from 1 millisievert to 20 millisieverts. For areas municipal governments are required to decontaminate, the central government will offer financial support for locations with 5 to 20 millisieverts of radioactivity and for spots with relatively high radiation levels, such as street gutters, even if the radiation doses in the area are less than 5 millisieverts.

The Minami-Soma municipal government plans to decontaminate private houses with the help of nonprofit organizations and volunteers. However, the costs of such measures place a heavy financial burden on the municipal government. Little progress has been made on decontamination work in four other municipalities located in the previously designated emergency evacuation preparation zone, lifted last Friday, between 20 and 30 kilometers of the troubled Fukushima plant.

Kawauchimura, 90 percent of which is covered by forests, plans to either cut down or prune all trees in the village due to concern for the health of forestry workers. The village predicts it will take 20 years to complete the operations. The village also faces difficulties, including where the cut trees are to be stored temporarily and how to secure jobs for forestry workers.

In late September 2011, Environment Minister Goshi Hosono said his ministry will issue a plan in October on how best to store the growing amount of radioactive soil and how long it must be kept in makeshift yards until proper temporary storage facilities are built. "Honestly speaking, it's really hard to choose a location to build temporary storage facilities," he said. "So it'll be difficult to specify them on the road map."

Japanese Armed Forces Clean Up Radiation with Brooms and Brushes

Reporting from Tomiokamachi, Fukushima Prefecture, Dai Adachi and Setsuko Kitaguchi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Self-Defense Forces members have begun decontamination work in the no-entry and expanded evacuation zones in Fukushima Prefecture, using only such low-tech implements as brooms, deck brushes and shovels.The central government has commissioned private companies to do decontamination work in some areas on a trial basis, but they, too, lack sophisticated resources, and some Environment Ministry officials involved with the decontamination work are frustrated by its slow pace. "The areas to be decontaminated are so wide. I wonder when the radiation levels will go down so residents can return home," one official said. [Source: Dai Adachi and Setsuko Kitaguchi, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 10, 2011]

As cold rain fell decontamination work by SDF personnel was shown to the media in Tomiokamachi, about nine kilometers from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant. Some SDF members used brooms to gather fallen leaves, while others trimmed weeds growing under trees or shoveled mud from ditches.At a first glance, it looked like a peaceful scene at a park. However, the about 300 SDF members were entirely covered by white protective suits, large surgical masks and green gloves. On the third-floor balcony of the town office, several personnel used buckets and rope to lower bags of gravel taken from the office's roof. "We've no choice but to do this by hand," an SDF official said.

SDF personnel also dug up soil in a 3,400-square-meter plot of grassland contaminated with radioactive substances, and carefully cleansed asphalt-covered areas such as a parking lot with high-pressure water sprayers. A dosimeter briefly displayed radiation levels of seven to eight microsieverts per hour during the cleanup. The central government has set a goal of lowering the radiation level to 20 millisieverts per year and 3.8 microsieverts per hour in the contaminated zones.

SDF members will be engaged in the work for about two weeks. "To attain the goal, we'll have to make our personnel finish a substantial amount of work," an SDF senior official said. The central government asked the SDF to do the decontamination work as an advance party, with the aim of securing rest areas for private decontamination companies and bases to store materials before the government starts a full-fledged decontamination project in 12 municipalities in the no-entry and expanded evacuation zones from January. About 900 SDF members currently are involved in that work at municipal offices in Tomiokamachi, Namiemachi, Narahamachi and Iitatemura of the prefecture.

"If we commissioned private companies to do the preparations, it would take about 2-1/2 months because we have to make an official notice and hold a bid. We wanted to secure at least storage bases by the end of this year," said Satoshi Takayama, parliamentary secretary of the Environment Ministry.At some places in the zones, the central government has commissioned private companies to do the decontamination, in model projects to find effective measures to rid the areas of radiation.

The decontamination of roads and highways will be given priority and start in January, followed by residential areas including private houses. It still is not certain how long it will be before residents can return home. "Not all the places have high radiation levels. There must be areas where people can return comparatively earlier. However, the targeted areas are large, so it will take a substantial time for some areas," a ministry official said.

Special Hose Used to Clean Contaminated Paving Stones

In January 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “An ultrahigh-pressure hose has proved highly effective in decontaminating roads constructed with paving stones that have been contaminated by radioactive substances released from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. The Japan Atomic Energy Agency, commissioned by the Cabinet Office to study decontamination technology, demonstrated use of the hose at Fukushima University. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 30, 2012]

Roads made from paving stones are difficult to decontaminate because radioactive substances tend to collect in grooves between the blocks. The ultrahigh-pressure hose, normally used to erase traffic markings on pavements, is owned by Kictec Inc., a Nagoya-based company. Two vehicles are required--one equipped with the hose to discharge water and the other to pump it up. The cost is about one-third of that needed to replace the paving stones.

In an experiment conducted in December 2012 the ultrahigh-pressure hose was found to reduce radiation levels one centimeter above the ground by 80 percent, while ordinary high-pressure hoses only reduced radiation levels by 30 percent to 40 percent. The ultrahigh-pressure hose is designed to pump water at such a velocity that it dislodges earth and sand, which is then sucked up by another pump. The water is then recycled after being filtered.

Decontamination of Houses

Koichiro Takano wrote Yomiuri Shimbun in November 2011, “The Date municipal government has become the first municipality to begin decontamination of houses within specific sites recommended for evacuation by the central government because of high radiation levels. The local government decided to decontaminate the houses on its own out of consideration for residents who wish to return to lives free of radiation fears as soon as possible. It is unclear, however, how effective the operations will be, as so far it has proven difficult to get radiation down to target levels. [Source: Koichiro Takano, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 16, 2011]

A total of 54 households in the Shimo-Oguni district of Ryozenmachi in Date were designated as sites recommended for evacuation at the end of June. The district, located in a mountainous area about 300 meters above sea level, is about 55 kilometers northwest of the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

As many of the households in the district are farmers, most of them have not evacuated. The central government designated 113 households in four districts in Date as so-called hot spots, where the annual amount of radiation is expected to exceed 20 millisieverts. Misa Sato, 65, wife of farmer Mikio Sato, 70, watched the decontamination efforts get under way with a look of relief. "I'm grateful that decontamination has started. If radiation levels at our house are lowered, our daughter's family will be able to visit us with their children," she said.

Describing the clean-up Takano wrote: “Four workers, clad in thick uniforms, helmets, goggles, masks and boots, began decontamination work at Sato's house recently. They were members of a building cleaning company in Date hired by the government. An official from a radiation control-related company in Tokaimura, Ibaraki Prefecture, oversaw the work.

The workers removed mud and fallen leaves using shovels and other means, and placed them into bags. They scraped moss from roof tiles and scrubbed gutters with brushes while flushing them out with water. They then cleaned a concrete floor using a scrubbing brush and pressurized water. Soil that was found to be contaminated with radiation was transported to a temporary storage site located near a forest in the district.One 37-year-old cleaning worker said with bewilderment: "Unlike ordinary cleaning, this dirt is not visible. We don't know how far we have to clean."

After the cleaning work was completed, the radiation level in the gutters dropped to 2.2 microsieverts per hour from 4 microsieverts. Three days later, an operation to remove topsoil in Sato's garden was conducted with the cooperation of city volunteers. However, when they scraped the soil away to a depth of five centimeters, the radiation level increased unexpectedly. It was an area where rainwater had seeped underground.

Model Decontamination

An experimental decontamination project began in December 2011 in parts of Fukushima Prefecture, including the town of Okumamachi, which is located within the 20-kilometer no-entry zone around the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. The project tested various decontamination methods to see how effective they are at lowering the level of radiation in the air. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 6, 2011]

The model project is scheduled to be carried out at 12 municipalities that include areas designated as no-entry or expanded evacuation zones, as the project aims to remove radioactive substances from wide areas. The decontamination operations began at the Okumamachi town office, about four kilometers southwest of the nuclear power plant, and on a hill near a primary school in Katsuraomura, about 25 kilometers from the power plant.

About 45 workers clad in protective gear collected fallen leaves and cut grass. High-pressure water jets were used to test the effectiveness of different methods on the rooftop of the Okumamachi town office--using cold water and hot water at a temperature of 50 to 60 C, and changing the duration of the spraying. As a result, it was learned that spraying cold water for about 10 minutes lowered surface radiation by about 40 percent, to 9.87 microsieverts per hour from 16.45 microsieverts.They also tried reusing the water after passing it through a filter. "We want to test various techniques to establish an efficient method to lower air radiation levels," said Kazuo Todani, an executive director at the agency.

Cleaning Up and Reducing Radiation Exposure an Endless Chore

Tetsu Joko wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Hachiro Miura, 68, gave up harvesting persimmons in autumn 2011 when radioactive cesium from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant was detected on the trees. He used high-pressure hoses and other methods in an effort to decontaminate about 90 trees. The water stripped the bark from the trees. Despite his efforts, anxiety continues to gnaw at him. "There's no guarantee cesium won't be detected in my persimmons this year. Even if it isn't, I'm not sure customers will buy them," he said with a sigh. [Source: Tetsu Joko, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 2012]

Yuko Abe, 38, who lives in the Watari district of Fukushima with her husband and their 22-month-old daughter, washed the walls of her house and removed surface soil from her garden in April last year. She was initially relieved when radiation levels in front of the house dropped. However, they returned to their previous levels a few weeks later.Abe stopped decontaminating her property after she was told by a radiation expert who inspected her house that wind and rain probably would carry more radioactive substances in the direction of her home.

The municipal government plans to start decontamination work in the area soon. But Abe is trying to protect her daughter from radiation exposure as much as possible by having the girl play in a room in the center of her house and avoiding windows where radiation levels are higher. Abe and her daughter stay elsewhere on weekends.

"There's no magical way to decontaminate the areas instantly. Our job is to prove our technology, even though it's low-tech," an official of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency, which is jointly conducting the decontamination project with the central government. Decontamination activities also are affected by the weather. If work is conducted in heavy rain, for example, removed soil will be washed away, which could spread radioactive materials. Decontamination cannot be conducted if snow piles up because the snow will throw off radiation readings and workers might scrape away more soil than necessary.

Companies Inflating Decontamination Costs

In October 2011 reports were emerging, according to the Yomiuri Shimbun, of companies charging exorbitant prices for decontaminating homes in Fukushima Prefecture. One resident complained to the prefectural government that they had received a bill for $12,000 from a local company for the decontamination of their house. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 21, 2011]

Some residents have approached private contractors directly with requests to decontaminate their houses, and there have been many cases in which companies have solicited residents with offers to decontaminate their homes. It is predominantly among these cases that problems have arisen.

As no companies had taken on decontamination work for residential properties before the nuclear power plant crisis, the new business opportunity has been seized by companies specializing in cleaning and decorating. A building maintenance company in Minami-Soma said, "If we calculate decontamination costs based on the way we usually clean houses, decontamination should come to about 200,000 yen to 300,000 yen per house."

However, the reality is that there is no standard cost for decontaminating houses. It depends on the work carried out: whether it includes removing radioactive substances from roofs and exterior walls or trimming trees. But a prefectural official in charge of decontamination who was told about the case of the resident charged 1 million yen, said, "That definitely is far too expensive."

Radioactive Soil

Much of the radiation that was left behind by the crisis at Fukushima nuclear power plant was in the soil in the area around the power plant. Radiation in air blows away. Radiation in water eventually disperses and is diluted. Contaminated plants die but official in soil remains for long time. To get ride often times the soil has to be physically removed and disposed.

In May, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Municipal governments in Fukushima Prefecture have taken it upon themselves to remove radioactive topsoil from children's outdoor play areas, with operations under way or planned at 217 locations. Efforts to clear the topsoil--expected to cost hundreds of millions of yen--come after abnormally high radiation levels were detected in playground areas in the prefecture, where TEPCO’s crippled nuclear power plant is located. Under government-set standards, children should not play outdoors for more than one hour a day if radiation levels exceed 3.8 microsieverts per hour...The Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry conducted radiation measurements at 56 playground facilities Thursday, and ministry officials said radiation did not exceed 3.8 microsieverts per hour at any of them... But authorities in five cities and one village in the prefecture have set stricter maximums of their own accord, indicating distrust in the government and reflecting anxiety felt by parents.” [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 22, 2011]

Forests to Be Used to Store Radioactive Soil

The Forestry Agency, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported, has decided to allow local governments to use plots of land in state-owned forests to temporarily store soil and rice straw contaminated with radioactive substances from the Fukushima nuclear power plant. Local governments will be responsible for preparing the land for the temporary storage sites, while the central government will shoulder the cost using its reserve fund for reconstruction. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 24, 2011]

Many local governments affected by the March 11 disaster are having difficulty securing storage sites for contaminated soil and other matter. Providing land in the state-owned forests may help resolve this problem. The sites will store soil removed in the process of decontamination and rice straw contaminated with radioactive materials. Local governments may ask to be allowed to store sludge from the water supply and sewage systems, as well as ash produced by incinerating it.

In principle, the temporary storage sites will be built in forests within the jurisdictions of local governments that have collected contaminated soil. If there are no state-owned forests with the jurisdiction of a local government, it will decide what to do in consultation with other local governments. The sites will be located tens or even hundreds of meters from residential areas. If a forest is near a water source, local governments will be required to consult with governments downstream before building temporary storage sites.

According to an Environment Ministry estimate, up to 28 million cubic meters of contaminated soil in Fukushima Prefecture should be removed as it is assumed to have a radiation dosage of 5 millisieverts or higher per year. If the soil is evenly piled up one meter high, the total area would be about 65 square kilometers, equivalent to half the area inside Tokyo's Yamanote loop railway line. Contaminated soil and other matter will be encased in waterproof materials. If the quantity to be stored is large, the contaminated material will be placed inside concrete containers or surrounded by concrete walls. As the sites are defined as temporary storage facilities, contaminated matter will not be buried.

Sunflowers and Getting Rid of Radiation

Sunflowers were widely planted. Experiments by the agriculture ministry showed sunflowers absorbed little radiation from the soil The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Japanese researchers who study space agriculture believe growing sunflowers will remove radioactive cesium from contaminated soil around the Fukushima No.1 nuclear power plant, and are planning a project to plant as many of the yellow flowers as possible.. They have invited people to sow sunflower seeds near the Fukushima Prefecture power station, hoping the sunflower will become a symbol of recovery in the areas affected by the nuclear crisis.” After the sunflowers are harvested, they will be decomposed with bacteria, according to a plan by a Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency group led by Prof. Masamichi Yamashita. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, April 23, 2011]

“After the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster, sunflowers and rape blossoms were used to decontaminate soil in Ukraine. Radioactive cesium is similar to kalium, a commonly used fertilizer. If kalium is not present, sunflowers will absorb cesium instead. If the harvested sunflowers are disposed of by burning them, radioactive cesium could be dispersed through smoke, which is why the researchers are considering using hyperthermophilic aerobic bacteria — used to produce compost — to decompose the plants. The decomposing process will reduce the sunflowers to about 1 percent of their previous volume, which will slash the amount of radioactive waste that needs to be dealt with.”

Where to Store 28 Million Cubic Meters of 'Hot' Soil

TEPCO barge Up to 28 million cubic meters of soil contaminated by radioactive substances may have to be removed in Fukushima Prefecture, according to the Environment Ministry.In a simulation, the ministry worked out nine patterns according to the rates of exposure to and decontamination of radioactive materials in soil, mainly in forests. The ministry found if all the areas which were exposed to 5 millisieverts or more per year were to be decontaminated, 27.97 million cubic meters of contaminated soil would have to be removed. The calculation covered 13 percent of the prefecture's area. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 26, 2011]

These figures indicate the size of the temporary facilities that will be needed to store the soil, and the capacity of intermediate storage facilities where the soil will be taken later. The assumptions were made using three categories according to yearly radiation doses in soil--20 millisieverts or more; 5 millisieverts or more; and 5 millisieverts or more plus some areas with contamination of from 1 to 5 millisieverts.

The three categories were divided further according to possible decontamination rates in forests--100 percent, 50 percent and 10 percent. The resulting nine patterns were broken down further to include "houses and gardens," "schools and child care centers" and "farmland." The ministry calculated that the largest amount of contaminated soil was 28.08 million cubic meters in the case of 100 percent decontamination in forests in the category of 5 millisieverts or more plus some areas with contamination of from 1 to 5 millisieverts.The smallest amount was 5.08 million cubic meters if 10 percent decontamination is carried out in forests with radiation doses of 20 millisieverts or more.

In the breakdown of areas with yearly radiation doses of 5 millisieverts or more, it was found 1.02 million cubic meters of soil should be removed from houses and gardens, 560,000 cubic meters from schools and child care centers and 17.42 million cubic meters from farmland. The total amount of contaminated soil with a yearly radiation dose of 5 millisieverts or more is 27.97 million cubic meters in the case of 100 percent decontamination in forests that cover an area of 1,777 square kilometers. The ministry made its calculation based on an aerial survey by the Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry and a land use survey by the Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry.

The usual practice is to remove soil up to a depth of five centimeters. However, a senior official said this depends on the location of the contaminated soil. Even though forests occupy about 70 percent of contaminated areas in the prefecture, the ministry does not believe it will be necessary to remove all contaminated soil, as long as the government restricts the entry of residents in mountainous areas and recovers cut branches and fallen leaves, according to the official.

The government still has not procured sufficient storage sites for contaminated soil, which has been temporarily buried in school yards or piled on vacant lots. According to the central government, contaminated soil should be collected at temporary storage sites by local governments. The government recommends placing impermeable sheets under the soil at locations far from living areas. The government also has no prospect of setting up intermediate storage facilities. Shortly before he stepped down, former Prime Minister Naoto Kan called on the Fukushima Gov. Yuhei Sato to set up facilities in the prefecture. The request was rejected.

Few Places Willing to Accept Radioactive Debris

In December 2011, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government began work to bury rubble left behind by the March 11th earthquake and tsunami in northeastern Japan. Tokyo began accepting large amounts of debris from Miyako City, Iwate Prefecture, for disposal last Thursday. The rubble is being broken into pieces or incinerated at facilities in the city and then transferred from a local incinerator to a landfill site in Tokyo port, where it was buried using large construction equipment. he metropolitan government said it plans to accept up to 500,000 tons of debris from Miyako and other disaster-hit areas by March 2014. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com November 8, 2011]

In November 2011 the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The number of local governments that agreed to accept debris created by the Great East Japan Earthquake in Miyagi and Iwate prefectures has fallen to less than 10 percent of the number released in April, according to a survey released by the Environment Ministry. The plunge is apparently due to radiation fears. Fifty-four municipalities and federations of cities and villages that perform selective functions such as waste disposal and firefighting said they would accept debris, the ministry said. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com Yomiuri Shimbun, November 3, 2011]

When a similar survey was conducted in April, 572 municipalities and federations agreed to accept rubble. If the 20 million tons of debris from both prefectures cannot be disposed of, reconstruction plans for the disaster-hit areas are likely to be adversely affected, observers said.

According to the ministry, six municipalities and federations said they already accept debris, and 48 municipalities and federations said they are looking into whether to accept it.The total amount of debris to be accepted was 4.88 million tons when the previous survey was conducted. However, the ministry did not release the amount Wednesday, saying many local governments did not specify how much they would accept.

The ministry also did not release the names of municipalities that agreed to accept waste. "If we release names, some municipalities will likely receive complaints from citizens, which may hinder their ability to accept debris," a ministry official said. "Under the current circumstances, it will be difficult to reach our goal of disposing of all debris in three years," the ministry official said.

Disposal Sites Refuse to Accept 140,000 Tons of Tainted Waste

In March 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: At least 140,000 tons of sewage sludge, ash and soil contaminated with radioactive materials has yet to be disposed of in Tokyo and six prefectures in the Kanto region following the crisis at the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, it has been learned. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 4, 2012]

Under the central government-set criteria regarding radioactive materials, sewage sludge and ash with radiation levels up to 8,000 becquerels per kilogram can be put in landfills. But an increasing number of final disposal sites refuse to accept contaminated sludge and ash even if it meets the criteria, according to a survey by The Yomiuri Shimbun. In other situations, soil removed during decontamination work has been left at the original sites.

When The Yomiuri Shimbun asked local governments in Tokyo and six other prefectures with waste water processing facilities how they have handled sewage sludge, it found a total of 103,100 tons of sludge--including that which has been incinerated and reduced--was still at the facilities. Of that, about 52,700 tons was in Saitama Prefecture, the most among the seven prefectures.

The Yomiuri Shimbun surveyed 24 facilities in Tokyo and four other prefectures where radioactive cesium above 8,000 becquerels had been detected in ash. The survey revealed about 6,500 tons of ash from general waste was still kept at the facilities. Of that, about 2,200 tons were in Ibaraki Prefecture and about 1,900 tons in Chiba Prefecture. As for polluted soil removed in decontamination work, The Yomiuri Shimbun looked at 51 municipalities in five prefectures, which have been designated by the central government as areas for close contamination inspections, and found about 30,400 tons of polluted soil was temporarily stored there.

Many local governments in the Tokyo metropolitan area do not have their own final disposal sites for sewage sludge and ash. The Nagareyama municipal government in Chiba Prefecture has about 750 tons of ash. The city previously sent ash to facilities outside the prefecture, such as one in Kosaka, Akita Prefecture, for final disposal.However, since a maximum of 28,100 becquerels of radioactive materials per kilogram were detected in ash in July, such final disposal sites refused to accept ash from Nagareyama. Even ash en route to the disposal sites was returned to the city.

Radioactive Soil Stored for 30 Years

In October 2011 the Japanese government announced that contaminated soil and waste would be moved to an interim storage facility in Fukushima Prefecture in around three years and final disposal would be carried out outside the prefecture 30 years after that. The government has not indicated a specific location or size of the interim facility. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 31, 2011]

Some local people have expressed relief that decontamination will continue, while others are adamantly opposed to having a storage facility built in their hometown. Many are bewildered as to why contaminated soil and waste must be stored for as long as 30 years in the prefecture.

"I'm not so worried now that the government has said the interim facility should be in use in three years," said Harumi Onuki, a 42-year-old caregiver in the Onami district of Fukushima city. A temporary storage site has been set up between 200 and 300 meters from her house.Onuki has two children--a primary and a high school student--and she feels uneasy about having contaminated soil and grass containing relatively high levels of radiation near her house. "I've always wanted the stuff to be moved as quickly as possible. My anxiety has eased a little," she said.

Fukushima Mayor Toshitsuna Watanabe said, "I think it's necessary to prepare to accept the facility but not on the premise that it will be the last disposal site." On the other hand, Katsutaka Idogawa, mayor of Futabamachi, a neighboring town, said forcefully: "I can't agree to have the interim facility built in my town. I don't want the residents to stop returning to the town."

Image Sources: Tepco. YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012