LIVING WITH EARTHQUAKES IN JAPAN

the shinkansen automatically shuts down

during an earthquake Balancing on several tectonic plates, Japan is one of the most earthquake-prone countries in the world, with more than 130,000 quakes logged in 2005. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “To geologists, earthquakes are a constant in the planet’s eternal becoming. To the Japanese, they are simply a constant. In a given year, there can be hundreds, usually barely discernible micro-events. They rattle the pictures on the wall, the china on the table, but they rarely stop the conversation." Even so according to Yomiuri Shimbun survey, 78 percent of Japanese worry about a major earthquake. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, March 28, 2011]

Donald Keene, a professor at Columbia and the dean of Japanese-literature scholars, said, “Very often, when I have been away from Japan for a while and come back, there will be a small earthquake, and I notice it and no one else in the room does. They laugh at me.” He added, “People expect this all the time, that they will be warned. But when a quake of great magnitude happens they are shocked. The world changes.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, March 28, 2011]

David Leheny, a political scientist at Princeton who is working on a project in Tokyo, told The New Yorker, “Earthquake consciousness is drilled into the young” — what you need to do, what you need to have ready. There is an earthquake-oriented gallows humor of daily life. People talk about the areas that would be hit hardest. They live with it in the back of their minds. More than San Francisco, there is a sense of certainty about earthquakes here—“the certainty that there will be a massive earthquake in Tokyo. And they live with that.” The New Yorker mentioned one scholar in Tokyo who guiltily described both the sense of horror at the event and the sneaking sense of relief that at least “the big one”—“the latest big one” — had not struck the capital when the earthquake and tsunami in 2011 hit northern Japan with the brunt of its ferocity. [Source: The New Yorker]

See Separate Articles:EARTHQUAKES AND JAPAN factsanddetails.com ; EARTHQUAKES: GEOLOGY, FREQUENCY, TYPES, ENERGY AND RESEARCH factsanddetails.com ; CAUSES AND PREDICTIONS OF EARTHQUAKES factsanddetails.com ; EARTHQUAKE DAMAGE AND EARTHQUAKE-RESISTANT BUILDINGS factsanddetails.com EARTHQUAKE SAFETY AND SURVIVAL factsanddetails.com ; EARTHQUAKE-RESISTANT BUILDINGS AND HOMES IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Earthquake Information Center earthquake.usgs.gov ; Wikipedia article on Earthquakes Wikipedia ; Earthquake severity pubs.usgs.gov ; Collection of Images from Historic Earthquakes Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, Jan Kozak Collection ; World Earthquake Map iris.edu/seismon Most Recent Earthquakes earthquake.usgs.gov ; Earthquake Pamphlet pubs.usgs.gov ; USGS Earthquakes for Kids earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/kids ; Earthquake Preparedness and Safety Surviving an Earthquake edu4hazards.org ; Earthquake Preparedness Guide earthquakepreparednessguide.com ; Earthquake Safety Site earthquakecountry.info ;

Earthquake Information for Japan Earthquake Information from Japan Meteorological Agency jma.go.jp/en/quake ; F-Net Broadband Seismography Network fnet.bosai.go.jp ; Wikipedia List of Earthquakes in Japan Wikipedia ; Major Earthquakes in Japan in the 20th Century drgeorgepc.com ; Earthquake Engineering and Disaster Prevention: Disaster Prevention Research Institute, University of Kyoto dpri.kyoto-u.ac.jp/web ; Japan Association of Earthquake Engineering jaee.gr.jp/english ; Earthquake Preparedness in Japan Earthquake Preparedness Survey whatjapanthinks.com ; Earthquake Research in Japan: Headquarters of Earthquake Research Promotion jishin.go.jp ; Institute of Geology and Geoinformation unit.aist.go.jp Research Center for Earthquake Prediction, University of Kyoto rcep.dpri.kyoto-u.ac.jp ; Earthquake Research Institute, University of Tokyo eri.u-tokyo.ac.jp ; 1923 Tokyo Earthquake: Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 dl.lib.brown.edu/kanto ; 1923 Tokyo Earthquake Photo Gallery japan-guide.com

Preparing for a Once in 1,000 Years 'Calamity’

Fumihiko Imamura, the director of the Disaster Control Research Center of Tohoku University, said after viewing the damage of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami: "We must think seriously of how to face the risk of an 'extremely low- probability calamity,' and how to hand down lessons learned for posterity." [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 18, 2012]

Japanese earthquake experience car The recent period of high economic growth, which enabled Japan's "miraculous" economic recovery and development, happened to occur during a phase of few large-scale natural disasters in the archipelago's history, according to some experts. The fact that many industries and groups of people could gather in places such as Tokyo and the Tokai region, which are vulnerable to natural disasters, may have been thanks to such good luck. With the unprecedented Great East Japan Earthquake and accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, the question now is how to prepare for and prevent damage from disasters.

How much should we prepare for extremely rare disasters said to occur once every 1,000 years? And what about recent extreme weather conditions in which conventional wisdom cannot work? During the Great East Japan Earthquake, the height of coastal seawalls affected the fates of those hit by the tsunami.

The tsunami overran an about 10 meter-high seawall in the Taro district of Miyako, Iwate Prefecture. However, a seawall measuring more than 15 meters high in the village of Fudai and another 12 meter-high seawall in the town of Hirono stopped the waves. The seawall in the Taro district, which was completed in 1978, cost more than 400 million yen in total. The Fudai seawall, completed in 1984, cost 3.5 billion yen. The cost of a bay mouth seawall in Kamaishi Port, which was destroyed by the tsunami, cost 120 billion yen. It is true that the higher the seawalls, the better. But a tsunami more than 15 meters high could hit in certain areas. Considering costs, it is impossible to make seawalls high enough to block every possible tsunami.

Former Fukuoka Gov. Wataru Aso, who served as president of the National Governors' Association, said: "It's impossible to take disaster management measures by assuming [it will be] the one that takes place once every 1,000 years. "The cost is unimaginable. I think 'software,' such as evacuation drills, are more important than 'hardware.'" In fact, experts said municipalities that practiced such drills and other "software" measures suffered less damage from the March 11 disaster.

Experts are paying more attention to this extremely rare type of disaster. For instance, once every 10,000 years or so, large volcanoes may have "catastrophic eruptions," the likes of which have not been witnessed by civilizations for thousands of years. Should this type of disaster occur, it could ruin not only a nation, but the entire planet. Experts at the Volcanological Society of Japan have begun holding symposiums with government officials to assess such risks. A magnitude-5.8 earthquake in the eastern United States, the first since the late 19th century, occurred in August. The quake caused a nuclear power plant in Virginia to automatically stop, leading to demands from U.S. experts for measures against extremely rare earthquakes.

Earthquake Warnings

If scientists believe there is a significant risk of a major earthquake occurring imminently a meeting is held by a six-member council at the Meteorological Agency. They give a report to the Prime Minister who holds a Cabinet meeting. If they believe there is a real risk they can issue a warning. Issuing a warning is not something taken lightly because if a warning is issued the shinkansen and many public facilities are shut down and this can greatly disrupt the economy and everyday life.

James Glanz and Norimitsu Onishi, New York Times,” Hidden inside the skeletons of high-rise towers, extra steel bracing, giant rubber pads and embedded hydraulic shock absorbers make modern Japanese buildings among the sturdiest in the world during a major earthquake. And all along the Japanese coast, tsunami warning signs, towering seawalls and well-marked escape routes offer some protection from walls of water. These precautions, along with earthquake and tsunami drills that are routine for every Japanese citizen, show why Japan is the best-prepared country in the world for the twin disasters of earthquake and tsunami. [Source: James Glanz and Norimitsu Onishi, New York Times, March 11, 2011]

Japan launched a new earthquake warning system in 2007. It uses sensors that pick up the fast-moving and less destructive P-waves produced by an earthquake and transmits a warning broadcast on television and radio before the destructive S-waves arrive, giving recipients of the message precious seconds to seek shelter.

The system gives people as much as a 50 second warning before an earthquake occures in places far from the epicenter. The system is only really effective for places away from epicenter. P-waves and S-waves arrive close together at places close to the epicenter, where warning would only be a matter of a couple seconds at most.

Eight earthquake warnings were issued the first year the system was in operation. The main problem with them is that few people actually were aware of the warnings. Japanese companies have begun developing cell phones ad other devises that can pick up the warnings better.

Japan also has a tsunami warning system that issues warnings on television. See Tsunamis

Disaster Alert System to Send Info to Phones

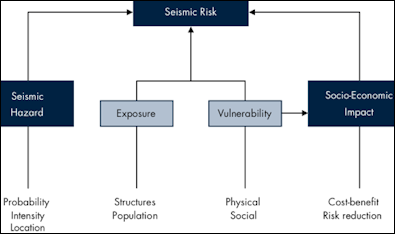

Earthquake Scientific Framework

The government is implementing a new disaster alert system to ensure the public can receive important information as soon as possible on their cell phones and through other channels. The planned system will enable mobile phones, cable TV connections and other devices to automatically receive emergency information, such as evacuation instructions from local governments and reports from the central government's J-Alert system. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 29, 2012]

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Under the current J-Alert system, which began operating in February 2007, the Cabinet Secretariat and the Japan Metrological Agency send emergency alerts--such as news of an attack by a long-range ballistic missile, as well as earthquakes and tsunami--to the Fire and Disaster Management Agency, which notifies relevant local governments via satellite. Municipalities then turn on disaster broadcast systems--usually automatic start-up devices connected to the J-Alert apparatus--to relay emergency information to residents via outdoor loudspeaker systems.

However, many flaws with J-Alert and other communication systems have been reported, particularly during the devastating earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011. By adopting a variety of steps, the government aims to make as many residents as possible aware of its disaster updates, according to officials.The planned system will include J-Alert reports, evacuation instructions or advisories by local governments, flood alerts, radiation reports following a nuclear accident, as well as road conditions and the status of transportation systems. The system also might add public information about shelters and other evacuation information after a certain period following a major disaster, officials added.

When the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, some wireless communication systems were damaged or lost power, and were unable to inform residents of evacuation instructions and advisories. Upgrading these systems would be costly, particularly for installing new loudspeakers. About 30 percent of local governments have not yet installed automatic start-up devices for the J-Alert system. Moreover, when the government conducted a nationwide disaster drill in September, the receivers at about 280 municipalities either did not emit the alarm or had problems receiving reports.

Earthquake Preparedness

After the Kobe earthquake, which demonstrated how unprepared Japan was for such a serious earthquake, the emphasis switched from predicting earthquakes to being better prepared for them when they strike. The result was a multimillion dollar education campaign and advise and subsidies for earthquake-proofing homes and other buildings.

The bullet trains have a system with seismographs that automatically shut downs the train at the first sign of an earthquake. Many factories in earthquake-prone areas have machines that automatically shut down when they sense vibrations from a quake. The Japanese gas company has installed meters that shut off the gas supply in the event of tremor. Nuclear power plants and other dangerous factories are also automatically shut down. Ideally, expressways are cleared so emergency vehicles can get through, factories are shut down and gas and electricity supplies are made safe. The public is informed on what to do.

On the outskirts of Tokyo, at a former U.S. Air Force base, a back-up capital has been set up as a command center in the event of a major earthquake. The rooms are sparsely furnished and contain computers and wall-mounted viewing screens. The basement is filled with food and a large kerosene generator. There is a well for water.

After the Kobe earthquake many people could not be rescued from the debris because of a lack of tools. As a result, some places have placed easily-acessible tools such a saws, crowbars, and axes in warehouses in schools and parks and have set up a system for service stations to lend their tools. But as the Kobe earthquake showed: no matter how much preparation is made it still often isn't enough. If a major earthquake occurs in Tokyo on a work day one of the biggest logical problem will be what to do with all the stranded commuters and other people too far from their homes to return by foot in the event the train system is crippled.

Virtually all schools and factories conduct regular earthquake drills and have a ready supply of safety helmets. Residents are taught that during an earthquake they should turn off all gas appliances and stand under a door frame for protection from falling debris. In elementary school, children are taught to seek cover under a desk. Approximately 27 percent of all homes in Tokyo have emergency supplies on hand in the event of an earthquake.

There are vending machines that offer drinks free of charge after earthquakes.

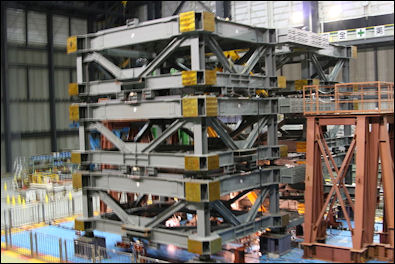

Stanford's NEESR-SG Controlled Rocking machine To train Japanese how to prepare for earthquakes special trucks have been outfitted with a table, two chairs, a bookshelf, a gas cooking stove, kerosene heater that are shaken by a powerful hydraulic system that can simulate earthquakes 50 times more powerful than the one that struck San Francisco in 1989. The NRCDP Earthquake Simulator is a giant hydraulically-powered "shakingmachibe " that is used to test horizontal and vertical movements on bridges, buildings and other structures.

Earthquake education includes seminars on emergency medical treatment, fire extinguishing and finding one’s way out if a smoke-field building. An instructor at an earthquake simulator at the Life Safety Center in Tokyo, which produces a simulated one-minute-long 6.9 temblor, told the Los Angeles Times, “Everyone here is surprised at the violence of the movement and how long it lasts. They say “I didn’t know the earth moved so vigorously.” And I tell them this is just a test. The real one is much worse, much more emotionality terrible.”

Earthquake drills are held throughout the country on September 1st, the anniversary of the Great Tokyo Earthquake in 1923 During earthquake drills in Japan children run through smoke-filled tunnels with wet handkerchiefs over their faces. Soldiers rehearse helicopter rescues. In 2007, more than 627,000 people took part in disaster drills across the Japan on Disaster Prevention Day. In 2008, more than 590,000 did.

Schoolchildren are taught to take cover under a desk when the earth begins to shake. When there is an earthquake some Japanese squat. On why this so, Hiroko Masuike, a New York Times writer who was born and raised in Tokyo said, “When we grew up, we had this training,” said my colleague “All the time we were told, “Go lower.”

Almost 400,000 Participate in Disaster Drills

Nearly 400,000 people participated in earthquake and tsunami drills nationwide during for Disaster Prevention Day in September 2012. In Tokyo, the central government held a mock emergency Cabinet meeting and the metropolitan government held a disaster drill in a neighborhood densely packed with wooden houses. The drill was based on a magnitude-7.3 inland quake striking Tokyo. In Tokushima, Kochi and other prefectures, large-scale drills were conducted to simulate the transport of people needing emergency medical care based on a magnitude-9 earthquake along the Nankai Trough in the Pacific Ocean. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 2, 2012]

According to the Cabinet Office, about 387,000 people participated in the day's drills. Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda chaired the mock emergency meeting on disaster management and received damage reports from various locations. Noda also held a mock press conference based on the assumption that the earthquake had caused serious damage. "I want everybody to act in a cool-headed manner," he said.

The metropolitan government conducted comprehensive disaster drills in about 30 locations, including near Nishi-Koyama Station in Meguro Ward and in Komazawa Olympic Park. About 6,000 people participated in the drills. The drill near the station assumed an inland quake had caused major damage in an area with many wooden houses. Residents practiced rescuing injured people from collapsed buildings and performing first-response firefighting using buckets.

Authorities predict that 5.17 million people will be unable to return home if a major inland earthquake hits Tokyo. At JR Meguro Station, participants acting as commuters evacuated to nearby shelters through the guidance of wireless disaster broadcasts, radio and Twitter posts. The central government's large-scale medical transport drill was based on a huge Nankai Trough quake with an epicenter off Shikoku that caused severe damage in Tokushima and Kochi prefectures. The drill involved the dispatch of about 1,000 members of disaster medical-assistance teams to quake-hit areas. Similar drills were also conducted in areas devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

In Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture, about 2,500 residents of coastal areas participated in the area's first disaster drills in two years. As part of the drills, the city conducted its first-ever tsunami evacuation exercises. In Sakyo Ward, Kyoto, which is within 30 kilometers of Kansai Electric Power Co.'s Oi nuclear power plant, the only nuclear plant in the nation currently running, an evacuation drill assuming an accident at the plant was conducted.

earthquake safety system

Earthquake Insurance in Japan

Because the premiums are so high, only 7.2 percent of households in Japan carry earthquake insurance. Only three percent of the residents of the prefecture that includes Kobe had insurance when the Kobe earthquake struck in 1995. Some policies are part of fire insurance policies. One report found that 580 cultural properties, including 113 national treasures, were vulnerable to earthquakes.

In Tokyo, earthquake insurance that pays $120,000 in benefits for a relatively quake-proof steel-frame house cost about $200 a year. People living in Miyagi and Iwate prefectures, areas struck by the earthquake and tsunami in 2011, pay $75 and $60 respectively for the same benefits, because those areas are considered to be less likely to be struck by an earthquake than Tokyo. Insurance premiums are higher in places considered more likely to be struck by a quake.

Japanese usually purchase earthquake insurance with fire insurance. The number of people holding earthquake insurance increased greatly after the 1995 Kobe earthquake from 5.18 million in 1995 to 12.27 million in 2009.

Earthquakes, Compensation and Profits in Japan

The Enright Real Estate Co has made handsome profits by spending hundred of millions of dollars to buy up old Tokyo buildings and making them earthquake resistant and then selling them or renting them at significantly higher prices.

After the Iwate-Miyagi earthquake in June 2008, families whose houses were destroyed received $30,000 in emergency aid. Those who stayed in temporary housing for many months received $8,000 to $20,000 according to the size of their family, people whose businesses were affected received $5,000 to $20,000 while those who lost their jobs because of the quake got $5,000. In Koei district up to $100,000 was given to people whose farms were damaged.

The Victims Relief Law ensures that homeowners will be compensated for the loss of property in the event of a disaster such as a flood or earthquake, Compensation, however, often falls short of what is necessary to replace property as it was. According to one survey 54 percent of the 7,976 houses nationwide damaged by natural disasters from April 2004 to December 2006 could apply for housing-related benefits under the law, Among them only 19 percent receive the full money for which they applied. Some prefecture and municipality governments have their own schemes which provide additional relief for disaster victims. The Tottori government gives victims $30,000.

Tokyo's Waterways Eyed as Emergency Earthquake Routes

Yohei Takei wrote in Yomiuri Shimbun, “In the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake, Tokyo's waterborne transportation network is attracting renewed attention as an alternative to road and rail transport. The March 11 disaster paralyzed Tokyo as roads were jam-packed with vehicles and pedestrians, and train services were halted. If, as feared, a strong inland earthquake occurs with an epicenter nearer to Tokyo, the damage to roads and related facilities could be severe. Supply chains for goods are also likely to be cut.

Therefore, the central and Tokyo metropolitan governments are considering how to utilize waterways, which have been used for transportation since the Edo period (1603-1867). Even the 200 yakatabune leisure boats in Tokyo may be brought into play. "As yakatabune have power generators and toilets, they can be used as disaster shelters. If necessary, they can carry people across rivers to neighboring prefectures," said Tetsuro Nakazawa, 41, president of Oedo, a company operating yakatabune services. If a tsunami follows an earthquake, yakatabune crews will be able to quickly take passengers to higher land.

Tokyo Yakatabune Rengokai, a business association of yakatabune operators, has signed an accord with the Tokyo Fire Department and other authorities to use canals and other waterways "for transporting people and supplies in the event of a disaster." About 200 boats, including the yakatabune, are covered by the accord. If all the boats are used, they would be able to transport about 12,000 people at one time. There are 61 docks, including some that have existed since the Edo period, which can be used as transportation bases in emergencies.

earthquake probabilities

Police to Ban Cars on 52 Routes During Major Quake

In March 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: The National Police Agency said Thursday it would ban the passage of regular vehicles on 52 expressway routes and other roads extending a total of 1,770 kilometers if a major earthquake directly hits the greater Tokyo area. The NPA's plan is based on the premise that a major earthquake, with its focus directly beneath the northern part of Tokyo Bay, hits the southern Kanto region. The aim of the traffic control is to free roadways to send rescue teams and relief goods to Tokyo as quickly as possible. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 9, 2012]

According to the NPA, it is the first traffic control plan for disasters that covers multiple prefectures. Prefectural police headquarters had separately prepared regulation control plans of their own for disasters, the NPA said. According to the plan, the NPA will designate the 1,770-kilometers covering 46 expressway routes, including all Metropolitan Expressway routes, and six principal roads, mainly in Tokyo and adjacent prefectures. After a major earthquake occurs, regular vehicles will be rerouted to undesignated roads, with only emergency vehicles and heavy machinery transport trucks allowed to use the routes.

The regulations will gradually be relaxed depending on the progress of recovery in quake-struck areas and other factors. The NPA discussed which routes to include with the Defense Ministry and the Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry. The section of the Chuo Expressway subject to the regulation will be extended to Nagano Prefecture, where Self-Defense Forces units are stationed. That of the Tomei Expressway will be extended to Aichi Prefecture to ensure the smooth transport of relief goods to Tokyo from Nagoya and surrounding municipalities.

Until now, prefectural police headquarters had prepared traffic regulation plans for disasters on their own, resulting in inconsistencies in policies where roads cross borders. Aichi and Nagano prefectural police headquarters have not prepared any traffic regulation plans for major earthquakes expected to directly hit the southern Kanto region. After the March 11 disaster, the NPA designated emergency routes crossing nine prefectures at 11 a.m. on March 12. However, if the NPA had prepared a regulation plan similar to the one it has planned now, the designation of such routes could have been conducted earlier, the police said.

Japanese Earthquake Rescue Teams

Japanese earthquake search and rescue teams are outfit with dogs, seismographic equipment and cameras at the end of optical fiber cables New rescue equipment is available that uses electromagnetic waves to detect the hearts beats and breathing of people trapped in the rubble. The machines can detect movement through concrete block three meters and perform many of the duties performed by dogs.

In the event of a major Tokyo area earthquake, a plan calls for the mobilization of 20,000 troops in 24 hours , with 17,000 more on the second and 37,500 more on top of that on the third day.

Japan lagged behind the United States , China and other countries in offering assistance to Haiti after it suffered an earthquake in 2010. Japanese rescue teams didn't rescue anybody in China after the Sichuan Earthquake in 2008.

Image Sources: Disaster Prevention Research Institute, University of Kyoto, USGS

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013