MANGA

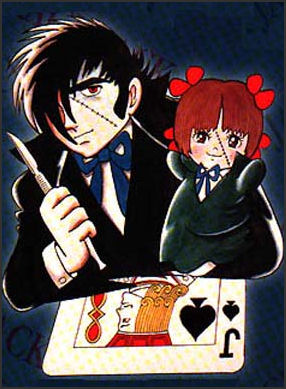

Black Jack

a classic manga by

Osamu Tezuka Manga (which literally means "vernacular and corrupt drawings") is a multifaceted style of comic books produced in Japan for adults as well as children. Many manga feature large-eyed, nymph-like characters, that appear distinctly Japanese to Westerners, and is a medium that uses text and pictures to present a reading experience that in some ways simulates the experiences of watching an animated film.

“As of 2010, “manga” accounted for 24.2 percent of the sales and 39 percent of the volume of all books and magazines sold in Japan, with their influence being felt in various art forms and the culture at large. Though some story “manga” are aimed at small children who are just beginning to learn to read, others are geared toward somewhat older boys and/or girls, as well as a general readership. There are gag “manga”, which specialize in jokes or humorous situations, and experimental “manga”, in the sense that they pursue innovative types of expression. Some are nonfictional, treating information of different sorts, either of immediate practical use or of a historical, even documentary, nature. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The manga formula wrote Holland Cotter in the New York Times, included "clearly outlined forms, toothsome colors and blandly smiling images of prepubescent innocence, sometimes laced with undercurrents of sex and violence...At their most inventive, they're like Disney on amphetamines, addictively pleasurable and weirdly, unpredictably perverse."

On appreciating manga Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times, a classic work is “fairly easy to pick apart on a drawing-by-drawing, or line-by-line basis. Don’t make that mistake. Its pleasures are cumulative; the book has a rolling, rumbling grandeur. It's as if someone had taken a Haruki Murakami novel; and drawn, beautifully and comprehensively, in its margins.”

There are 200 different manga magazines, with each carrying an average of 15 regular serials. Favorite manga over the years have included “Death Note” by Takeshi Obata, “Eyeshield 21" illustrated by Yuke Murata and “Black jack” by Osamu Tezuka. Major manga publishers include Kodansha Ltd, Shueisha Inc and Kadokawa Group Publishing Co,

In July 2011, a 44-year-old man was found dead and buried under magazines in his apartment in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, police said. Yuichi Yasuda, a company employee, is believed to have been buried when the stacked magazines collapsed during an earthquake the day before. Police from Matsumoto Police Station found Yasuda on his back, covered in piles of magazines 70 to 80 centimeters high. The quake measured an intensity of upper 5 on the Japanese scale of 7. Although it is believed the magazines fell on him, the cause of his death has not yet been determined, according to police.

Madeleine Schwartz wrote in The New Yorker, “The layout of manga translations can be confusing. In order to preserve the original orientation of the images, the book remains printed as it is in the Japanese, which means that one reads it right to left, even within individual panels. Such printing is a source of tension among publishers of such translations, who must weigh the distortion of imagery with the potential discomfort of their readers.” [Source: The New Yorker, Madeleine Schwartz, August 10, 2010]

Websites and Resources

Blue Planet Links in this Website: MANGA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR TYPES OF MANGA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR MANGA AND FAMOUS MANGA ARTISTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MANGA FANS AND COSPLAY IN JAPAN AND ABROAD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; OSAMU TEZUKA, MANGA AND ANIME Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

ANIME Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ANIME FILM AND TELEVISION SHOWS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HAYAO MIYAZAKI ANIME Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILM INDUSTRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILMMAKERS AND FILMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MEDIA, RADIO, NEWSPAPERS AND TELEVISION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TELEVISION PROGRAMS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CHILDREN’s TELEVISION SHOWS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Good Websites and Sources on Manga: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Manga.com manga.com ; Free Manga using Scanned Pages onemanga.com ; Manga Fox mangafox.com ; How to Draw Manga howtodrawmanga.com ; Essay on Manga and Anime aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Krazy World of Manga, Anime and Video Games aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Ultimate Manga Guide (last updated 2004) users.skynet.be/mangaguide ; Rei’s Manga and Anime Page (last updated in 2005) mit.edu/people/rei/Anime ; Manga Video manga.com ; Comic Yamasho Stores comic-yamasho.jp-stores.com ; Kyoto International Manga Museum kyoto-international-manga-museum

Books: “Manga Manga! The World of Japanese Comics and Dreamland Japan”; “Manga! Manga!”by Fred Schodt; “Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga” by Frederick L. Schodt (Stone Bridge Press); “Adult Manga” by Sharon Kinsella (Cuzon Press, 2000); “Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics” by Paul Gravett (Laurence King Publishing, 2004); “Manga: The Complete Guide” by Jason Thompson (Dek Ray); and “One Thousand Years of Manga” by Brigitte Koyama, a professor of art history and comparative literature at Musashi University in Nerima Ward, Tokyo, where she specializes in ukiyo-e, Japonisme, manga and anime. Related books include “Japanamerica” by Roland Kelts (Palgrave Macmillian, 2007) and “Encyclopedia of Japanese Culture” by Mark Schilling. “Millennial Monster”by Prof. Anne Allison is about the fantasies behind toys, games, anime and manga.

Frederik Schodt was awarded the Japanese government’s Order of the Rising Sun.

History of Manga: A History of Manga dnp.co.jp/museum ; Manga Gaku matt-thorn.com/mangagaku ; Brief History of Manga comicreaders.com ; Tokyo Manga and Anime Shops : Nakano Broadway is a shopping street in Nakano Ward that houses many shops selling items related to pop idols, manga and anime characters. Tokyo Character Street is located on the Yaesu side of JR Tokyo station. It is an 80-meter-long underground street with 15 shops offering hundreds items bearing likenesses of anime figures like Doremon and Ultraman and new characters like NHK mascots Zoomin and Charmin and Monkey D. Luffy from “One Piece” as well characters like Totoro form Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli. Manga Magazines and Publishers: Shonen Jump shonenjump.viz.com ; Viz Media www.viz.com ; Tokyopop tokyopop.com ;

Otaku Urban Dictionary urbandictionary.com ; Danny Choo dannychoo.com ; Otaku Dan Blog otakudan.com ; Otaku Generation Blog generationotaku.net ; Dumb Otaku dumbotaku.com Otaku story in the Washington Post Washington Post ; Otaku History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Academic Pieces on the History of Otaku cjas.org ; cjas.org and cjas.org ; Early Piece on Otaku (1990) informatik.hu-berlin.de ; Man, Nation, Machine informatik.hu-berlin.de ; Otaku from Business Perspective nri.co.jp/english ; Otaku Sites The Otaku, Anime and Manga Portal and Blog theotaku.com ; Otaku World, Online Anime and Manga fanzine otakuworld.com ; Otaku Magazine otakumag.co.za ; Otaku News otakunews.com ; Danny Choo dannychoo.com ; Spacious Planet Otaku Blog spaciousplanet.com ; Otaku Activities Maid Cafes stippy.com/japan-culture ; Male Maid Café yesboleh.blogspot.com ; Akihabara Book: “The Best Shops of Akihabara — Guide to Japanese Subculture” by Toshimichi Nozoe is available for ¥1,000 by download at http://www.akibaguidebook.com Akihabara Murders : See Government, Crime, Famous Crimes . Websites: Picture Tokyo picturetokyo.com ; Akihabara News akihabaranews.com ; Akihabara Tour akihabara-tour.com ; Otaku story in Planet Tokyo planettokyo.com

Popularity of Manga in Japan

Hundreds of costumed

manga fans at a cosplay event Manga is everywhere in Japan. During rush hour, the subways are filled with salarymen reading them. In convenience stores young people flip threw their pages. At school, boys and girls chat about their favorite characters. Supermarkets are filled with piles of them, which are opened, from Western point of view, from the backcover. There are manga cafes, bookshops, conventions and websites.

Manga make up nearly half the book sales in Japan. You see them read by people of all ages. While much of manga is aimed at adults, children are the largest market.

Manga embraces a $5 billion market. Explaining its success Tokyo mayor and ardent nationalist Shintaro Ishihara said, “The Japanese are inherently skilled at visual expression and detailed work.” He expressed this view as a challenge to Disney, “I hate Mickey Mouse,” he said. “He has nothing like the unique sensibility that Japan has.”

American cartoonist and Yale-trained lawyer Charles Danzing told Kyodo news that compared to American comics, manga are more “visually intriguing and cinematic. It’s visually animated, with lots of angles. The stories are real, with story arcs and endings that are darker and more intriguing.”

Yu Ito, a researcher at the Kyoto International Manga Museum, told the Daily Yomiuri, “In Japan, there’s no clear distinction between adult culture and youth culture. This kind of environment has nurtured the development of manga.”

The manga, anime, video game, television and media industries are all interrelated. Many popular manga characters find their way into video games and anime DVDs. Many films and television shows are based on or inspired by manga series. Sometimes several films and television shows are inspired by a single series. Many television shows are based on manga stories. Theater dramas and musicals such as “Tenisu no Oji-sama” (“Princes of Tennis”) have also been based on manga. The term Japan Cool is sometimes used to describe the interest in manga and anime and modern Japanese culture in general.

Famed mangaka Jun Ishikawa told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Nowadays many TV and film productions are based on manga. People turn the pages of manga when they are short of ideas.” Another famed mangaka Fujiko Fujio said,”Manga has become a form on a par with literature or film. There was a time when manga were ranked beneath movies and novels, but the form has risen to the same level since the emergence of Tezuka-sensei.”

Appeal of Manga

Manga page in German Roland Kelts wrote that Japanese culture manifested anime and manga is “attractive in part because it feels freer, less fettered by focus groups and financial reports. Taboos about violence, sexuality or racial imagery can be directly confronted in forms that have for decades flown under the proverbial radar. Japanese pop culture is cheap to make and distribute, and is marginal in character and by nature — more like anarchic punk music than corporate products such as Disney films.”

Jean-Marie Bouissou, a big manga fan and a professor at the Paris Institute of Political Studies, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “"Manga illustrates various fields including politics and economics, which mirror all aspects of Japanese society. It also deals with current issues. Japan is the only country where manga has become part of the mass media.” The success of Japanese manga can be attributed to "noninterference by parents and government officials," according to Bouissou. Cartoonists were able to draw freely for children aged from about 10 to 14. On the other hand, both French and U.S. manga had restrictions placed on what could be drawn for that age level. "Spontaneity was the key to the development of Japanese manga," the professor said.[Source: Tetsuya Tsuruhara, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 13, 2010]

Robert Reed wrote in the Daily Yomiuri,”One of the things that make manga so popular is their ability to give us an easy, entertaining and unpretentious approach to great stories, which always have the potential to start us thinking seriously about ourselves and about life.”

After the earthquake and tsunami in 2011 Kanta Ishida wrote in Daily Yomiuri that he “read a story online about a person who donated a copy of the latest issue of manga magazine Shonen Jump to a Sendai bookstore that was unable to stock the issue because of the quake. The man had purchased the copy in a different prefecture. That single copy has since been read by more than 100 children at the shop. One of the readers was a boy who travelled to the bookshop by bicycle from his home 10 kilometers away. I couldn't hold back the tears.” [Source: Kanta Ishida, Daily Yomiuri, April 1, 2011]

Origin of Manga

12th century emaki Art historian and manga expert Brigette Koyama-Richard traces the origin of manga back to emaki illuminated scrolls made in the 11th century (See Classic Art). One of Japan's most beloved scrolls “Choju Jinbutsi Giga” ("Caricatures of Frolicking Animals and People") is regarded by some as the oldest example of manga. A 12th century work by an unknown artist, it shows a rabbit wrestling with a frog while two other rabbits look on, laughing and cheering. In a sumo-like pose the frog is trying to trip up the rabbit while biting his long ears. The characters look like something out of a comic strip or a book of fables. Otaku dismiss the “origin of manga” accolade saying “Choju Jinbutsi Giga” has some wonderful animal figures but is missing to many elements that make manga what it is.

Koyama-Richard said that nishiki-e prints made in the Edo period (1603-1867) were often satirical and instilled with humor and fun, qualities found in modern manga “I think they share a similar espirit, satisfying the purpose of entertaining people.” The term "manga" was coined by the famous wood block print artist Katsushika Hokusai (1761-1849). Although he produced graphic images he did not produce true manga that tell narrative stories.

True manga has its roots in 19th century one-panel and later multi-panel newspapers and magazine cartoons that depicted political, satirical and humorous subjects. Some also trace its roots to the Japanese written language, which has so many symbols and characters it wasn’t easily adaptable to movable type, and often it was just as easy to make wood blocks with words and illustration as it was to make wood block with long texts. By contrast, the Roman alphabet with is 26 symbols was adaptable to movable type.

Early History of Manga

Late 19th century

propaganda poster In the 1920s and 1930s comic books became popular, especially ones with adventure stories and children's cartoons. One of the most popular characters from this era was “Norakuro”, a dog in the Japanese army created by the artist Tagawa Suiho.

“Kamishibai”, picture stories shown mainly on the street, were popular before World War II. They were sort of like 20th century versions of ukiyo-e and were used to illustrate enka music (a sentimental style of Japanese music) that was often about feuds and revenge. Kamishibai were made for the masses with the aim of reducing stress and providing an escape from the drudgery of their ordinary lives.

Interculturally exchanges helped manga develop. French art nouveau artist took inspiration from Japanese ukiyo-e prints and Japanese mangaka were inspired by Art Nouveau painters such as Alphonse Mucha.

Early_Meiji_Era.jpg)

Meiji-Ear pictorial Soji Yamakawa is sometimes called the grandfather of manga. He made graphic, detailed drawings and painting in the 1930s, 40s and 50s for “emonogatari” — illustrated stories’such as the Tarzan-like “The Boy King”, “Tiger Boy” and “Kenya, the Boy”. Yamakawa began his career making kamishibai picture stories. Sheigeri Komatsuzaki was another influential illustrator that worked at the same time as Yamakawa.

Before World War II, the precursors of manga were mostly simple drawings. There were few details in the pictures. Yamakawa’s work and emonogatari in general provided dramatic and engaging pictures for stories, The main difference between emonogatari and modern manga is that modern manga has much of the dialogue, text and story in word balloons or boxes.

After World War II one of the most popular four-panel newspaper comics was” Sazae-san”, a humorous cartoon still popular today about an ordinary housewife and her family created by Hasegawa Machiko.

The switch to true manga occurred as illustration became the main vehicle of conveying a story. This took palce in the early 1950s when comic books like Shonen Jump for boys and Ribon for girls debuted. The comic books featured characters with large round eyes that resemble manga characters popular today. When Shonen magazine was launched helicopters flew out over the countryside to drop leaflets about the event.

Osamu Tezuka's Manga

Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989) has been called “the god of manga” and the “founder of anime.” He is credited with giving manga a cinematic style. He used a combination of framing, sequences and juxtaposition and even written sound effects to give print media a dynamic- quality that it otherwise lacked,

With the appearance of writer-illustrator Tezuka Osamu after World War II, so-called “story “manga”,” or illustrated publications in comic book format, developed in a somewhat unique way in Japan. At one time, the main readers of such publications were people born during the “baby boom” of 1946-1949, but as those readers grew older, many different types of “manga” came into being. Beginning in the 1960s, “manga” readership steadily expanded to include everyone from the very young to people in their thirties and forties. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Some say the first manga character was Tezuka Osamu's “Tetsuwan Atomu”. Frederick Schodt wrote, “the main thing that Tezuka did, I think, is that he took the American comic book format and basically decompressed it...So where in traditional American comic books you might have one scene that’s depicted with one page, Tezuka would use 10 pages or 20 pages or even 30 pages...Some of Tezuka’s stories became very long, several hundred even thousands of pages long, which enabled him to do things more like what writers and film directors do.”

Schodt, who translated some of Tezuka’s work into English, also said, “Visually, you can see that a lot his influences came from American animators, such as Walt Disney and Max Fleisher. But in terms of content, a lot of his influences came from Russian literature. Tezuka was a big fan of Russian literature.” On the Russian-inspired pieces Schodt said, “A lot of these designs are also directly out of theater. If you look at the stage design, the background, and you read these manga pages, you can see that this was taken right out of the stage design and put right in the page.”

The big round eyes so common in manga are said to have originated with Osamu Tezuka. Some have suggested he was inspired by Betty Boop.

Some consider Tezuka’s “Black Jack” to e one of the best manga of all time. It ran in Shukan Shonen Champion from 1973 to 1983, featuring the dark hero Black Jack, an unlicensed surgeon who can cure people of most anything as long as they pay his medical fees. The series featured life and death situations and E.R.-like operation scenes. His arch enemy was Dr. Kiriko, who among other things practiced euthanasia for hire. Some regard it as Osama Tezuka masterpiece. The series has recently been brought back as a movie made by Tezuka’s son Macoto Tezuka.

Manga Grows with the Introduction of Shonen Magazine and Adult Manga

The appearance in 1959 of the two weekly children’s “manga” magazines, “Shonen Magazine” and “Shonen Sunday”, served to firmly establish the sort of “manga” culture we see today. Both magazines put out a succession of extremely popular stories. Beginning in the 1980s, another “manga” magazine, “Shonen Jump”, remained for many years at the center of “manga” culture, with a weekly circulation of over 6 million and affiliated marketing systems for animation and video games. Most typically, children’s “manga” stories feature young characters and depict their growth as they fight against their enemies and build friendships with their companions. However, as their readers grew older, the readership figures for these children’s “manga” magazines dropped. By the end of the 1990s the weekly circulation for “Shonen Jump” had dropped to around 3 million. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“What became popular in their place were “manga” magazines targeting older readers. Originally aimed at young men in their 20s and 30s, these “manga” come with a wide range of styles and topics — issues relating to life as a student or adult, or social issues and economic matters — capturing a wider demographic of readers. From the mid- 2000s, so-called “”moe manga”,” or “crush “manga” — dealing with love and infatuation became a very popular genre. “”Moe” — is a Japanese slang word that refers to the strong feelings people get for certain characters. The characters are drawn with rounded lines and exaggerated features; the stories are not based on combat or fantasy like the children’s “manga” but generally develop around the everyday lives of normal female high school students. Some “moe manga” have been animated, and this, in turn, has widened the audience. The “manga”-for-girls genre has also become prominent. Female “manga” artists born in the 1960s, as well as those of the “baby boom” generation, came to demonstrate their talents in the 1970s and 1980s. They gradually widened the range of artistic expression for “manga” productions. Delicate psychological depictions are made through special types of illustrative techniques not usually seen in “manga” produced primarily for boys.

Junzo Ishiko, Manga Critic

Junzo Ishiko (1928-1977) was a famous art critic who reviewed manga in the 1960s and '70s when the art form was considered "kitsch." Kanta Ishida wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “The notion of subcultures within art did not exist at this time, meaning Ishiko was a pioneer, one of a handful of critics who subverted traditional modes of thought by evaluating manga's cultural value. Despite manga's meteoric rise in popularity and the massive growth in the vocabulary used to describe this art style, I believe that no one has made shrewder judgements on this form of expression than Ishiko. [Source: Kanta Ishida, Daily Yomiuri, March 2, 2012]

An example of text displaying Ishiko's foresight is in Manga Geijutsu Ron (Manga artistic theory), published by Fuji Shoin in 1967. "Paintings have sophisticated spiritual values. Any educated person who believes manga...only has kitsch, recreational values probably doesn't understand the importance of creativity at all," Ishiko said. Manga is a common subject of study at universities today, but this practice only developed during the last 10 years or so. A professional art critic must have needed great courage to utter the comments that Ishiko was making 45 years ago.

In 1967, Ishiko and his colleagues published a magazine called Manga Shugi (manga-ism) to discuss obscure mangaka such as Yoshiharu Tsuge, who authored Neji-Shiki (Screw-style) and Sanpei Shirato, who made Kamui Den (The Legend of Kamui). Ishiko is also known for embracing and promoting the concept of kitsch within the art scene. Ishiko's desire to find beauty in objects that people often overlook, and collect them... formed the roots of the contemporary otaku spirit.

He died young at the age of 48, but Ishiko's ideas can still be read in several books. Manga/Kitsch: Ishiko Junzo Subculture Ronshusei (Manga/kitsch: a compilation of Junzo Ishiko's subculture theories), was released in December, and is a collection of his work that had not been published in book form previously. A catalog of the recent exhibition is also available in book form.

Later History of Manga

Manga takes on more

sexual overtones Until the early 1960s, manga remained primarily geared for children. In the 1960s, manga oriented towards young adults emerged partly to keep the baby boomer audience as they grew from children into adults. As the market grew manga diversified, reaching a point that there were almost as many kinds of manga — romances, sports stories, science fiction and historical fictions — as there were kinds of books:

Some regard the mid and late 1960s as the golden age of manga and prose series like “Tomorrow’s Joe” and “Kyojin no Hoshi” (“Star of the Giants,” a baseball manga).

By the 1980s the manga industry had captured 40 percent of the publishing industry in terms of volume, with half purchases by young adults. But because manga were so cheap manga it accounted for less than 25 percent in monetary terms.

Manga was able to grow so fast because it produced products that people wanted and produced them in high volumes at prices low enough that children and young adults could afford them. Most of the manga have been black and white because they are much cheaper to make.

Manga and anime were given a bad name in the late 1980s when they were connected with Tsutomu Miyazaki — a psychopathic killer who killed four children and cannibalized two of them and left an ear of one of them in a box at the house of one of his victims — who was found to have a lot of manga and anime in his apartment. Some blamed the crime on “harmful comics” and called for a banning of manga and the closure of shops that sold it.

The manga industry reached its peak in 1995 when each issue of the weekly manga magazine Shonen Jump was read by an estimated 20 million people (one sixth of Japan's population). After 1995, the manga industry began declining, in part because of a declining birthrate and the popularity of the Internet, video games and cell phones. The industry continues to slowly shrink but still remains large.

Sales of manga magazines has decreased for 10 consecutive years as of 2005, when sales dropped five percent from the previous year to reach ¥242 billion. In 2005, paperback manga sales reached ¥260 billion overtaking magazines for the first time. These the way manga is being marketed is changing. More and more people are reading manga on the Internet and with their cell phones.

Former Prime Minister Taro Aso is a big manga fan, reading more than 10 comic magazines a week, and routinely giving street speeches in Akihabara, the otaku (nerd) center of Tokyo. As foreign minister he established the International Manga Award, which he described as “the Nobel Prize of Manga.” “Golgo 13", a classic manga about a professional assassin, is said to be Aso’s favorite manga. At a time when he headed a group that aimed to regulate pornographic manga he was known as “Rosen Aso” because of his fondness of “Rozen Maiden”, a manga with many beautiful girls dolls.

Japanese Government and Preserving Manga

Hatsune Miku Corolla Under the administration of former Prime Minister Taro Aso, the Cultural Affairs Agency was criticized for wasting taxpayers' money when it proposed building a state-run facility dubbed the "animation pantheon" as a center for exhibiting comics and animation. The agency decided to use an existing facility for that purpose and is thinking of establishing a digital archive museum. [Source: Kenichi Sato, Yomiuri Shimbun, September 23, 2011]

Public libraries and other facilities do not house sufficient manga materials. Kaichiro Morikawa, an associate professor at Meiji University, promoting the Tokyo International Manga Library project, said: "Precious manga materials are collected by individual fans. It's necessary that libraries and museums accept these collections and establish a system to hand them down to future generations."

Shuzo Ueda, secretary general of the Kyoto museum. Told the Yomiuri Shimbun, "Ukiyo-e in the Edo period [1603-1867] was thought of as having little value, but it was highly regarded in the United States and Europe, causing Japanese to rethink its value. Our efforts will have a major impact 100 years from now."

Manga Text and Stories

A-bomb explodes in

Barefoot gen Manga stories can be quite sophisticated. Many prominent Japanese writers and illustrators contribute to manga magazines, which are often more like illustrated literary and news magazines than comic books. Manga have also provided television and film with many non-animated stories and characters.

Adults and teenagers like manga stories because the speak more directly to them and are not patronizing or overly moralistic. Manga stories — whether they are about robot wars, salaryman fantasies or samurai dramas — often revolve around heroes and their families. This contrasts with American superheroes that often tend to be lone individualistic types.

It has been said that the Chinese characters (“kanji”) are ideally suited for manga because they have broad meanings and can be quickly understood with a quick glance. Manga expert Takeshi Yoro told the Daily Yomiuri, “Manga appeals to people whose brains have been trained to instantly grasp the overall meaning of a panel, or even an entire page or two at once. This is possible when the page lay out is done well.”

Manga frames often merge in TV-like sequences with pans and close ups. The texts is full of meaningless expressions like "doki, doki," "mukkaa" and "ohohohohoho" and written sound effects called “onomatopoeia”. There are also coded messages. The manga and anime expert Gilles Poitras for example has pointed out that a bloody nose "is associated almost exclusively with men looking for scantily clad or undressed women."

Manga Characters

Many manga and anime characters have big dewy eyes, dual-gender faces and childlike Caucasian features even though they supposed to be Japanese adults. For the most part they are stateless, having no clear national or racial characteristics. The male characters are often nerds or muscular super heros. The women often have baby faces ensconced long, spikey, hefty hair styles and plopped on improbably voluptuous, long-legged bodies.

Many manga and anime characters worry a lot and struggle with self-doubt and conflicts between their desire to perform good deeds and their flaws. Many heroes have a dark side and often this dark side is explored in great length as opposed to hinted at as is often the case with American super heroes.

Manga, Sex and Violence

Categories of sex manga include shojo (girl's manga/anime), yaoi (manga/anime aimed at women and featuring beautiful men who love other men) and cheesecake (pornographic material aimed at men.)

Much of the sex depicted by male artists is heterosexual or “yuri” (“girl on girl”). Much of the sex depicted by female artists is “yaoi” (boy-on-boy). The male figures in the yaoi manga tend by emasculated and non-threatening rather than overtly muscular and masculine. Many yaoi boy look like girls with large eyes, and lithe bodies. The plots tend to be sappier with more emphasis on kissing and romance than sex. The fact that two gay guys are in it give an appealing mystique.

Explicit depictions of sex acts and graphic violence are common features in manga. “Shonen” mangas for boys often feature hands slipping under panties of young girls and savagely violent science fiction and adventure stories. Salarymen comics have wish-fulfilling stories about business who beat up their bosses and have wild sex trips in Thailand. One particularly notorious manga called “Rape-Man” was finally yanked off the racks because of criticism.

Even though manga are often very violent Japan is by no means a violent society. "The Japanese have very refined skills in differentiating between fantasy and reality," wrote Frederick Schodt, author of the 1993 book “Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics”. Georgetown University professor Daniel Unger added, "In America, the choice was for comics control. In Japan it was for gun control.

"I think Japanese comics in general are a playing out of the subconscious," Schodt told the New York Times. "Maybe they fill a role similar to dreaming. You work out your stress, explore youth fantasies, and then you go back to work and normal life."

Image Sources: 1) 5) Osama Tezuka site 2) 6) 12) exorsyst blog, 3) National Museum in Tokyo, 4) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 7) 9) Hector Garcia, 8) Japan Zone, 11) Ray Kinnanae, 13) Amazon and Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013