ANIME

Dealing with Bullies Japanese animated cartoons, known as “anime”, feature doe-eyed characters like those found in manga and themes that are close to Japanese. Describing the appeal of Japanese animation, one editor wrote in Wired, "Japan's animated futuristic fantasies carry on a mad love affair with the threats — and possibilities — of technology."

Anime specifically refers to Japanese commercial animation. Anime is different from conventional animation due to the fact that Japanese creators were never bound by the 20th-century convention that animation was something solely for children. Anime is a broad medium that ranges from the purely innocent to the pornographic. Some of it fetishizes young girls. In Japan the manga, anime, video game, television and media industries are all interrelated. Many popular manga characters find their way into video games and anime DVDs.

Around a hundred animated programs air on Japanese television every week. Many are broadcast in prime time and are aimed at families to watch together. And while some programs have found their way to the West many of them have not. Ninja, yokai and transformation are particularly important subjects in anime, Koyama-Richard said. "[Ninja manga] Naruto is one such example. The same can be said for Studio Ghibli's Pom Poko and Spirited Away," she said.

The Tokyo International Anime Fair in late March 2008 welcomed 289 exhibitors and 126,622 visitors. The first event in 2002 drew 104 exhibitors and 50,1633 visitors. At the booths are models dressed up as characters starring in new anime films. Cruising through the halls are people in robot, dinosaur and maid costumes. Art schools seek out new students. Software companies show off their latest digital anime-making technology. Sales people look for new markets for new anime and video games. There is also a The New York Anime Festival.

Books, Websites and TV Stations Devoted to Anime

Links in this Website: MANGA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR TYPES OF MANGA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR MANGA AND FAMOUS MANGA ARTISTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MANGA FANS AND COSPLAY IN JAPAN AND ABROAD Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; OSAMU TEZUKA, MANGA AND ANIME Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;ANIME Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ANIME FILM AND TELEVISION SHOWS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HAYAO MIYAZAKI ANIME Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILM INDUSTRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILMMAKERS AND FILMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MEDIA, RADIO, NEWSPAPERS AND TELEVISION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TELEVISION PROGRAMS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CHILDREN’s TELEVISION SHOWS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Good Anime Websites and Sources: Crunchyroll crunchyroll.com . Crunchyroll is an Internet portal for anime downloads that began as a free fan file-sharing site and grew into a for-profit site that charges users fees that go to the producers of the anime. Free Anime Streams on Watch Anime watchanimeon.com ; Free Anime Streams on Zomganime.com zomganime.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Tokyo International Anime Festival tokyoanime.jp ; Anime News Network animenewsnetwork.com ; Anime Books: “Anime: from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle” by Susan J. Napier (Palgrave, 2001); “The Anime Companion” by Gilles Poitras (Stone Bridge Press, 1999); “Anime Revolution” by Ian Condry, a Harvard professor; “Rough Guide to Anime” by Briton Simon Reynolds.

Anime critic Helen McCarthy is the author of nine books on the medium, including the exhaustive and essential “The Anime Encyclopedia: Japanese Animation Since 1917" .

“Japanese Animation: From Painted Scrolls to Pokemon” by Brigitte Koyama-Richard, a professor of art history and comparative literature at Musashi University in Nerima Ward, Tokyo, where she specializes in ukiyo-e, Japonisme, manga and anime. In the book Koyama-Richard hopes to prove to Western audiences an oft-denied link between the "high art" of ukiyo-e prints and emakimono illuminated scrolls and Japan's modern manga and anime. Images in the 245-page coffee-table book date as far back as the early 17th century, before journeying through the history of anime with about 500 images.

Articles and Essay on Anime: Essay on Manga and Anime aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Useful Filmography on Anime aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Essay on Teaching Anime aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Essay on Dawn of Anime aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Anime Blogs Random Curiosity randomc.animeblogger.net ; The Anime Blog theanimeblog.com ; Japan Underground Blog hamblogjapan.blogspot.com ; Anipike anipike.com/ ; Suginami Animation Museum director Shinichi Suzuki

Places That Sell Anime Right Stuf Anime Superstore rightstuf.com ; Anime Corner animecornerstore.com ; Anime Nation animenation.com ; Krazy World of Manga, Anime and Video Games,; Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com ; Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Zoom Movie zoommovie.com ; Animax is a satellite channel that specializes in anime. It debuted in 1998 and claims 41 million viewers in Japan and is broadcasts in 46 other countries. Among the classic that are featured are “Dragonball Z”, “Mobile Suit Gundam”, “Astroboy”, and “Lupin III”. Animex is owned by Sony. The Cartoon Network exclusively airs Japanese anime after midnight.

Otaku Urban Dictionary urbandictionary.com ; Danny Choo dannychoo.com ; Otaku Dan Blog otakudan.com ; Otaku Generation Blog generationotaku.net ; Dumb Otaku dumbotaku.com Otaku story in the Washington Post Washington Post ; Otaku History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Academic Pieces on the History of Otaku cjas.org ; cjas.org and cjas.org ; Early Piece on Otaku (1990) informatik.hu-berlin.de ; Man, Nation, Machine informatik.hu-berlin.de ; Otaku from Business Perspective nri.co.jp/english ; Otaku Sites The Otaku, Anime and Manga Portal and Blog theotaku.com ; Otaku World, Online Anime and Manga fanzine otakuworld.com ; Otaku Magazine otakumag.co.za ; Otaku News otakunews.com ; Danny Choo dannychoo.com ; Spacious Planet Otaku Blog spaciousplanet.com ; Otaku Activities Maid Cafes stippy.com/japan-culture ; Male Maid Café yesboleh.blogspot.com ; Akihabara Book: “The Best Shops of Akihabara — Guide to Japanese Subculture” by Toshimichi Nozoe is available for ¥1,000 by download at http://www.akibaguidebook.com Akihabara Murders : See Government, Crime, Famous Crimes . Websites: Picture Tokyo picturetokyo.com ; Akihabara News akihabaranews.com ; Akihabara Tour akihabara-tour.com ; Otaku story in Planet Tokyo planettokyo.com

Appeal of Anime

Unlike American animation Japanese anime is often made for adults not children. Explaining why he liked anime one American fan said, “It’s deep. The ones that are serious [have] a lot of emotions, a lot of adult parts, and the ones that are comedy are just funny. I like the Japanese sense of humor.” A spokesman for the Anime channel said, “Compared to American animation, which is produced to target younger age groups, Japanese anime features well-structuredstories that are entertaining for adults.”

Brigitte Koyama-Richard said that part of the appeal to people who live in the West is anime's depiction of day-to-day life in Japan. "In anime, you can see tatami-matted rooms, lots of rice and school uniforms. They are simply different and unique in the eyes of Westerners...There are people who immediately link Japanese anime to sex and violence. But anime has much more than that. I wanted to express that it has a number of aesthetic parts to it," she said.

One anime fan told the New York Times, “Most American cartoons deal with simpler themes. These are more serious and complicated.” His friend had a different view. He did. “I’m just in it for the blood and gore. Anything with a robot shooting other robots, I’m there.” The Norwegian animator Anita Killi told the Yomiuri Shimbun that animators in Japan “like to express things about themselves and their immediate surroundings, their counterparts in Europe tend to make works that are deeply related to their society.”

Roland Kelts author of “Japanamerica” told the Daily Yomiuri that hallmarks of Japanese anime include “jerky, hyperkinetic action, technically stateless or even Western-looking characters, visceral violence and a complex, multifaceted, episodic storyline.”

Linking the popularity of manga and anime with popularity of Pokeman, Kelts told the Daily Yomiuri, “This whole generation of kids grew up with an acquaintance of anime style. And they wanted more of it as they got older. They left Pokeman behind, but they wanted more of that style.”

Kelts said, “So much of anime is successful because of what is left out, whether it is something aesthetic, such as certain lines that are left out, or actually a designation. This is not a rabbit, it’s not a fish or a mouse, it’s a Pocket Monster...So not only is it minimalistically drawn so that you’re leaving out key lines, you don’t know what ths lines would be because you don’t know what the thing is in the first place. So it [offers] so much more freedom, both for the viewer and the artist.”

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Japanese developed from the nation's climate and geographical features. Understanding that background and communicating in the language are necessary to produce anime, he said."Kawaii" and "setsunai"--these adjectives are essential to understanding anime, yet it's difficult even for professional translators to find the right words to convey the appropriate nuances. The terms are sometimes literally translated as "cute" and "poignant," respectively, but such leaden renderings hardly begin to do justice to the rich spectrum of thoughts and emotions behind the two words. That's why the word "kawaii" is recognized internationally, while the concept of "setsunai" is understood by young people overseas mainly through watching anime. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, January 20, 2012]

Otaku

See Manga Fans

History of Anime

The early creators of Japanese animation started out making works inspired by their adoration of U.S. animation. Japanese animator forged their own identity, with the term "anime" referring to Japanese commercial animation.

In her new book, “Japanese Animation: From Painted Scrolls to Pokemon” , art historian Brigitte Koyama-Richard links the "high art" of ukiyo-e prints and emakimono illuminated scrolls with Japan's modern manga and anime. "Since antiquity, people around the world have wanted to create moving images, but how this was done varied from culture to culture," Koyama-Richard, who chronicled the history of manga in One Thousand Years of Manga, told The Daily Yomiuri. "In Japanese Animation, I illustrate how this was done in Japan, and how it is linked to the traditional arts." [Source: Kumi Matsumaru, Daily Yomiuri, December 10, 2010]

Koyama-Richard argues that centuries-old artistic traditions form the basis of anime and give it its roots. “Japanese Animation” is divided into six sections: "Animation's Long Journey Through Time," "Pre-cinema and Great Inventions," "The Big Production Companies," "The Empire of Manga and Animation: The Role of the Big Publishers," "Kawamoto Kihachiro, Grand Master of Puppet Animation" and "Revival and Consecration of Japanese Anime."

In the book, Koyama-Richard interviews 20 anime industry leaders, such as film directors and animators, while explaining the history of traditional arts and anime she uncovered through her own research. Answering her questions, for example, mangaka Shigeru Mizuki says he loved looking at scary paintings of the Buddhist vision of hell at a nearby temple when he was a boy, and he took his inspiration from yokai monsters of the past, especially those of ukiyo-e artist Toriyama Sekien (1712-1788).

Stop-motion animator Kihachiro Kawamoto recalls being the type of boy who loved watching kabuki and traveling theater performances. He says puppets and dolls, when used in theater or animation, have a deeper significance than it might seem on the surface, and that in the Far East, they originally served as intermediaries for communicating with the divine. The notion also is found in bunraku theater.

Rintaro, who goes by one name, was involved in classics such as Astro Boy and Galaxy Express 999. He was a big fan of the ukiyo-e by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, and that his influence can be seen in his animated film “Yona Yona Penguin” .

Early Anime

Astroboy The oldest known Japanese animated film is the animated short “Namakura-gatama” (“Blunt Samurai sword”). Released in 1917 and made by pioneering animator Junichi Kuchi, it is about a samurai who buys a blunt sword and tries it out by attacking a express messenger only to be badly beaten by the messenger. The film lasts only two minutes.

Many people trace the beginning of anime to Tajii Yabushita's animated feature “Legend of the White Serpent”, an adaption of a Chinese fable, which was shown in 1958. The film was produced Toei Animation, a company that was found I n 1956 by Hiroshi Okawa (1897-1971) and was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy in the late 1950s but went on to become the pioneer of Japanese animation and helped provide employment, training and an outlet for creativity for anime masters like Osamu Tezuka and Hayao Miyazaki.

Toei animation made their films by tracing lines from sketches onto celluloid sheets and adding color by hand. The company was particularly known for its pasty-faced, flat human figures and personified animals such as the monkey, panda and fox in “Saiyuki” (1960).

Saiyuki was the studio's third film. Inspired by a famous Chinese story “Journey to the West” and marketed in the United States under the name “Alkazam the Great”, it was a collaborative effort by Yabushita and Osamu Tezuka. Toei remained the leader in Japanese anime until the 1970s.

Kenzo Masaoka, Pioneer in Japanese Animation

Makoto Fukukda wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Kenzo Masaoka was a pioneer of Japanese animation. He left an indelible mark on the genre, by, among other things, coining the term doga, or motion picture, as the Japanese translation of animation. Born in 1898 to a family wealthy enough to own its own noh stage, Masaoka himself performed noh and took lessons in tsuzumi, or Japanese hand drum, and taiko drums. The multifaceted Masaoka also learned oil painting with painter Seiki Kuroda. He entered the world of film in 1925. Having worked as cameraman and actor, he began to produce manga films, something he had been interested in from childhood. He produced Chikara to Onna no Yononaka (The World of Power and Women), the nation's first talking manga film, in 1932 and Benkei tai Ushiwaka (Benkei vs Ushiwaka), the first film made with prescoring, in which images are made to fit previously recorded music or lines in 1939. Kumo to Churippu (The Spider and the Tulip), which was released in 1943, achieved very high marks for technical excellence and was said to have influenced mangaka giants such as Osamu Tezuka and Leiji Matsumoto. [Source: Makoto Fukukda, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 24, 2011]

Animation expert Takashi Namiki, a friend of Masaoka's, said the artist tried to pursue not only the fun of watching moving images but also the building of a virtual world in which characters behave in a dynamic way as they do in Disney films. "I think his ideals are continuously being upheld by his protege Yasuji Mori and Hayao Miyazaki, who studied under Mori," Namiki said. The film's story about a pretty ladybug being chased by a ferocious spider then getting rescued by a tulip is said to have come under military scrutiny because of its poetic nature without war themes.

But animation director Sunao Katabuchi, who worked on Kiki's Delivery Service under Miyazaki, said the combination of the ladybug, which is like those seen in traditional Japanese children's pictures, and the spider with long legs and straw boater, can be compared to the contrast of Japan with the United States. "While the spider has dynamic and exaggerated movement reminiscent of Disney or Fleischer Studios, the ladybug's swaying movements are depicted more naturally and gracefully. He must have had the idea, at that point, of creating Japanese-style animation," Katabuchi said.

Masaoka's method of depicting realistic everyday life and building a story based on the details of it can be considered the essence of Japanese anime. That is very clear from Studio Ghibli productions or Mai Mai Miracle. "The fact that works like Keion!, an anime about the everyday life of a high school girl, were popular in Japan can be attributed to Masaoka's influence," Katabuchi said.

Masaoka retired because of illness after the war, but continued to work in the field, producing anime scenes in the special effects TV program Magma Taishi, and teaching younger artists. He died in 1988 leaving his latest project, Ningyohime (Little Mermaid), unfinished. But if weren't for the seeds he planted, the current giant tree of Japanese animation, with its many creative and artistic flowers, might not have grown.

Osamu Tezuka, See Separate Article, Popular Television Shows and Film, See Anime Film and TV Shows

Pioneering Anime Scriptwriter Masaki Tsuji

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in The Daily Yomiuri: Scriptwriter Masaki Tsuji knows how anime was developed. The TV man, born in 1932, created many scripts of such original manga as Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, Princess Knight and Triton of the Sea, as well as those of popular TV anime including Sazae-san and 8 Man. He is currently one of the original storywriters for Meitantei Conan (Case Closed). [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, December 29, 2012]

In 1954, Tsuji entered NHK as part of a first batch of recruits hired fresh out of university. At that time, most Japanese didn't have TV sets at home. Tsuji had to do everything from producing, directing and preparing props. "We had no time to go around begging for help to make programs. Also, I happened to like writing scenarios, so I wrote drama scripts under various noms de plume," Tsuji said. "Back then, every show was aired live. It was kind of a race every second. I met Mr. Osamu Tezuka at that time. "I went on and on about his manga. He then told me, 'You know more about my manga than I do.' That's how we started working together," he said.

There was a time when Tezuka told Tsuji how he envisioned his anime would look on TV. However, given the way the industry was back then, it was thought to be impossible. To realize his own dream, Tezuka established Mushi Production in 1962 to air anime on TV. The following year, Astro Boy was broadcast for the first time. Tsuji was writing a script for 8 Man when he was asked by Tezuka to help produce Astro Boy. The TV anime series quickly caught up with the original manga, and Tezuka constantly had to focus on producing original stories.

Masaki Tsuji Describes the Early Days of Making Anime

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in The Daily Yomiuri: Under the circumstances, Tsuji sometimes churned out six scripts a week--an astonishing volume compared to screenwriting today. "It was much easier to sit down and write stories than juggle several works at once for live TV programs," Tsuji said, adding that those who made anime were the busiest. "They didn't have time to sleep and were always fighting exhaustion. It was a race to see whether they dropped their pencil first or collapsed," Tsuji said. "But the hardest worker was Mr. Tezuka. He created anime to be aired on TV week after week. Nobody had done that before. It was like an announcement to society that anime had emerged as a professional career." [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, December 29, 2012]

There was no precedent in the world for making a 30-minute anime every week. In the meantime, Tsuji rewrote scripts over and over until everybody was satisfied with the storyline and the structure of introduction, development, turning point and conclusion. Being meticulous about everything from plot, background, character-setting to voice acting was already a common practice in the early days of anime production.

At the time, Tsuji said, it was a common misconception that anime had no future. But looking back, he sees that many children grew up watching his anime and some even became part of the next generation of creators. Asked about the current solemn mood in Japan, Tsuji said everybody surely has a sense that we're in a crisis, but that such a feeling alone will only lead to more negativity. "Have dreams that can be realized. By fulfilling those small dreams one by one, the achievement can turn out to be great," he said. "And say something big about your small dream. That's something I learned from Mr. Tezuka.

"Mr. Tezuka used to say, 'Astro Boy will earn more than a 30 percent viewer rating,' and people would say he's tooting his horn again. But his tall tales eventually became everybody's dream. What's important is to go back to the basics of 'doing what you love,'" Tsuji said. The economy may be haunted by this notion of "Do what we must." We should remember that our economy grew when we were all doing what we wanted to do. Anime and fashion should not be appropriated by a "cool Japan" strategy to make up for our financial troubles. The strategy should be to reinforce Japanese creativity.

Television Anime Versus Movie Anime

Feature-length Japanese animated films can be categorized overall as either a standalone original work or a theatrical-release edition of a television animation series. Pioneering examples of the latter include the movies of Tezuka Osamu (Astro Boy”, etc.) and Matsumoto Reiji’s “Space Cruiser Yamato” (1977; released outside Japan as “Star Blazers”) and “Galaxy Express 999" (1979). Popular long-running television animation series such as “Crayon Shinchan”, “Doraemon”, and the phenomenally successful “Pokemon” (“Pocket Monsters”) release feature-length productions on a regular basis. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

TV anime and cinematic anime are very different. On television it's all about presenting the characters in an engaging way within the framework of a limited number of drawings and a limited budget. Kozo Morishita of Toei Animation told the Yomiuri Shimbun: "[We learned that] if you endow the female protagonist with generous breasts, it puts a smile on kids' faces. Also, we turned the limitations associated with static images into a plus by effectively employing very detailed drawings of robots and such like. Working within such constraints let staffers heighten their powers of expression. It may have been a slightly unrefined approach, but in their pursuit of each protagonist's "cool" factor, the staff helped coalesce the traditions of Toei Doga's production methods. [Source: Makoto Fukuda, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 3, 2011]

"TV anime attracts viewers through the accentuation of popular characters, whereas movies can afford to spend a long time concentrating on story composition, development and presenting a world view," Morishita told the Yomiuri Shimbun. "Within these two genres, the director's job is completely different. But when you tackle these roles, you find that it becomes easier both for yourself and for the people who come after you."

Makoto Fukuda wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Morishita brought the full range of his skills to bear on “Saint Seiya” , which was produced in conjunction with Shueisha Inc. and its publication Weekly Shonen Jump. The project ate up large amounts of time and money: Clouds were drawn with multiple gradations, lavish action scenes were common and staffers poured their hearts and souls into the work.” Morishita recalls, "We used far too much cash, and consequently, I was made a producer so I could learn how to disburse funds appropriately."

In 1978, to deal with a shortfall in personnel, Morishita traveled to South Korea and trained staff there. Five years later, at the invitation of U.S. firm Marvel, he began visiting the United States to help make and direct The Transformers, the success of which brought great benefits for Toei Animation.

Anime Controversies and Internet Anime

In May 2008 Muslims took offense to a 90-second segment in “Jojo’s Bizarre Adventures” which depicts Dio Brando, a villain picking up a Koran and examining it as he orders the execution of the hero and his friends. Attention was brought the image in a pirated version of the anime series with Arabic subtitles and drew a great outcry in Arab and Islamic web forums.

The Japanese government issued an apology as did the publisher, Shueishi Inc., and the animator of the series . The creators of the series insist the presence of the Koran was a mistake and was not intended as disrespect. The scene from the story in question is set in Egypt. For reference the animator went to the library and found an Arabic book, which he drew in the comic. The book turned to be the Koran, which the anime creators didn’t realize because the couldn’t read Arabic.

Frog is the creator of a popular online-Flash-animated comedy “Himitsu Kessha Taka no Tsume” (“Eagle Talon”) that was turned into a successful television series that in turn produced two movies including “Eagle Talon: The Movie II — The Black Oolong Tea Who Loved Me”. The story is about a middle-aged man named and Soutou and a secret society called Taka no Tsume who aim to take over the world and make everybody happy by ruling the Internet. Frogman first made a name for himself in 2004 by posting films on his website made with Adobe’s Flash animation software. The first Eagle Talon movie won an award at a the New York International Film and Video Festival in 2008.

Anime in the United States

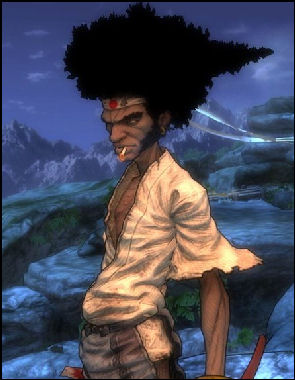

Afro Samurai “Barefoot Gen”, the first manga to be translated into English, became animated in 1983. As of 2001, more than 40 different Japanese animated cartoons were being broadcast of U.S. television. Among the more popular ones are “Dragonball Z, Digimon, Sailor Moon, Gundam Wing, Tenchi Muyo, Outlaw Star” and “Ronon Warriors”. Many of them are shown on the Cartoon Channel in the United States.

“Dragonball Z” is the best-selling anime series in the United States It is comprised of more than 400 episodes and 18 features Other anime with big following in the United States include “Bubblegum Crisis” by Horoski Inoue; “Full Metal Panic” by Chris Patton; “Mobile Suit Gundam” directed by Yoshiyuki Tomino.

There are quite a few companies at work bringing anime to the United States. They include of Japanese Bandai USA, a subsidiary of Bandai Visual, and Geneon, a subsidiary of Dentsu in Japan.

Anime has helped bring new audience for J-pop and Japanese rock groups like X-Japan, Gackt and Luna Sea. X-Japan music is featured in some popular anime titles.

Many non-Japanese watch fansubbed anime television shows online just days after they appear in Japan. The sale of anime dropped from $500 million in 2002 to $400 million in 2006. The number of titles declined from 756 in 2005 to just over 500 in 2007. The reason for the decline is “pressure from illegal online alternatives.” Many anime fans feel the they have no choice but watch fansubbed versions of new releases rather than waits months or even years for the official versions to arrive,

Marketing Anime Online Overseas

The anime industry in North America is focused on streaming video and online simulcasts of Japanese TV programming. Christopher Macdonald, CEO of animeNewsNetwork.com, the largest online anime news Web site outside Japan, wrote that the partnership, called Funico, was "more important than many people may realize," adding that he hoped more joint ventures between distributors and streaming sites would follow.

"The thing about anime is that it has to focus on online," he says now. "It can't wait for TV. The quantity [of anime programs] on TV has diminished. Young networks that carried anime in the past, like Cartoon Network, have realized that it's more profitable to own a franchise than to license it. "In North America, the industry forced people for years to buy anime they hadn't actually seen," he says.

The diminished market for the physical distribution of anime has long been anticipated by savvy industry players, whose efforts to shift to digital are beginning to pay off. Texas-based anime distributor Funimaton Entertainment had entered into a licensing agreement with Japan-based online file-sharer NicoNico via its global portal."It's all about content windows," says Lance Heiskell, Funimation's Director of Corporate Strategy. Heiskell points out that anime distributors now need to offer content through a diverse array of channels. "Simulcasts, DVD and Blu-ray, digital download to own, ad-supported streaming, Netflix and broadcast. It has to be a coordinated effort. Our goal is to have our content on all platforms, devices, retailers and physical media so people can easily get exposed to anime and fall in love with the shows and genres." While still in its infancy, the Funimation-NicoNico tie-up (called "Funico") has resulted in one big recent collaboration: the broadcast of the Jan. 20 premiere in Los Angeles of Fullmetal Alchemist: The Sacred Star of Milos.

Christopher Macdonald, CEO of AnimeNewsNetwork.com, says the absence of TV broadcasting in the U.S. anime market has made digital delivery essential. Heiskell sees TV exposure as a key difference between the Japanese and overseas markets. TV enables audiences to sample unique content, he notes, by flipping through channels without making commitments or choices, recalling the way radio used to function for pop music. In Japan, anime is broadcast throughout the day and especially late at night, when more adventurous or provocative series can get valuable airtime.

Despite what Heiskell calls "gloom and doom" reports about physical products, Funimation remains committed to its North American DVD and Blu-ray businesses. He points me to an industry report issued earlier this month mentioning a 20 percent spike in Blu-ray spending in 2011, and adds that despite the shrinking shelf space in brick-and-mortar outlets, Funimation's sales via online retailers such as Amazon and anime specialist Rightstuf.com are increasing. "[DVD and Blu-ray] are probably 80 percent of our overall business," Heiskell says. "Our fanbase has a collector mindset. They like to collect, display and show physical ownership of the shows they love. Online streaming is actually supporting our physical sales. In our consumer survey, seeing an episode online is the number one reason fans cite for purchasing a DVD or Blu-Ray. You can't display an anime collection that's on your computer."

Still, Heiskell is hardly celebrating the latest crises at Bandai and Media Blasters. anime industry players don't view one another as opponents, he explains. "People don't realize that the [anime conventions] are more like summer camps. People that are supposedly competitors are more like friends. Whenever a company struggles, it's not good for the industry. We need that friendly competition."

Crunchyroll

Crunchyroll.com is the largest and longest-running online portal for anime and related content outside of Japan. Kun Gao, cofounder and chief executive officer of the company, founded Crunchyroll as a fansite with four American friends, all of whom were driven by their passion to moonlight as Internet anime pirates. As the site's popularity skyrocketed, Gao quit his day job to manage it full-time. [Source: Roland Kelts, Daily Yomiuri, November 25, 2011]

Roland Kelts wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Other fansites proliferated, while anime producers in Japan saw DVD profits dwindle. Crunchyroll and its founders, operating the most popular pirate portal, realized they were choking off the very roots of their own growth. As I wrote three years ago in this column, they bit the bullet in 2008, officially going legitimate (i.e. legal) on New Year's Eve 2009--but not until they'd spent a full year trekking across Tokyo obtaining licenses to Holy Grail titles like Naruto and Bleach.

Anime and Hollywood

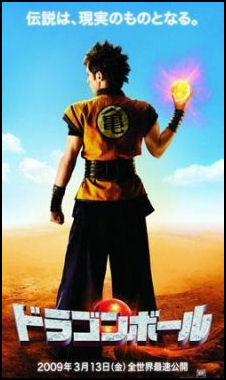

Dragonball movie “Transformers” and “Speed Racer” “both based on popular Japanese manga and anime — have been made into successful Hollywood movies. Toby Maquire is involved in adapting “Robotech” and Leonardo DiCaprio is involved in marketing a film of Katsuhiro Otomo “Akira”

A Hollywood-produced “Astroboy” is scheduled for release in the summer of 2009 with voices from Nicholas Cage, Donald Sutherland and Nathan Lance. See Astroboy. Steven Spielberg is planning to remake Mamoru Oshii’s “Ghost in the Shell” and “Titanic”’s James Cameron is making “Battle Angel”, based on the manga “Gundam”.

Shinji Aramaki was the key designer of the Hollywood blockbusters “Transformers” and “Robotech”. He also directed the new “Appleseed” films.

“Speed Racer” was made into a feature computer-anime film made by Andy and Larry Wachowski the creators of “The Matrix” . Speed’s voice was done by Emile Hirsh. His mother’s and father’s voices were provided by Susan Sarandon and John Goodman. Christina Ricca did Trixie’s voce, The plot is twisted, improbable, hard to follow but disposable and not really necessary. The main draw or put off, depending on your taste, are the awesome but numbing effects that are like those experienced on a very powerful acid trip. The film reportedly cost $120 million to make.

Japanese-Americans also made their mark. Los-Angeles-based Iwao Takamoto created the Scooby-Doo characters and directed the classic “Charlotte’s Web”. He also worked on “The Flintstones, 101 Dalmatians, The Jetsons” and other Disney and Hanna Barbara projects. He named Scooby-Do after the final phrase of Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night”.

Other Japanese-American anime collaborations include “Bakugan Battle Brawlwes 14" , the story of human boys and girls that possess balls and turn into monsters when they fight; and “Heroman” , about a boy that finds a robot that becomes a giant when it is struck by lightning. The former first appeared in Japan in 2007 and debuted a year later in the United States, where it generated a popular card game. Heroman was conceived Stan Lee, the American comic-book legend behind “Spiderman” and “X-Men” and brought to life by Bones, the animation company behind “”Fullmetal Alchemist” .

Astroboy movies, See Astroboy

Anime, Disney and Marvel

Japanese cereal on the Simpsons In March 2008, Disney announced that it would team up with Japanese studios, including Toei, to produce products aimed for the Japanese market. One idea call from the production of animation with Disney characters marketed towards Japan.

In August 2008, American comic book producer Marvel announced it was teaming up with Madhouse, a renowned Japanese animation studio, to produce anime series that will premier in the spring of 2010 in Japan. A spokesman for Marvel told the New York Times , that the entire stable of Marvel characters and stories will be reimagined and redesigned for Japanese tastes, “It will create an entire parallel universe for Marvel.” Marvel is the source of many of the great comic characters and characters for blockbuster films such as Superman, Batman, Spiderman as well the Fantastic Four and the Silver Surfer.

Image Sources: xorsyst blog, Hector Garcia, Anime gallery, Japan Zone, Goods from Japan

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2012