SUSHI

sushi “Sashimi” is sliced raw fish. “Sushi” is raw fish served with rice. There are two kinds of sushi: “nigiri-zushi” (raw fish placed on a cube of rice), the most common type of sushi, and “maki-zushi” (seaweed-wrapped discs of rice with tuna, cuttlefish, prawns, cucumbers, egg and pickled radish in the middle, wrapped with a bamboo mat). There are other kinds of sushi such as “inari-zuchi” (rice served is a pocket of sweet tofu) and “chirashi-zushi” (a layer of rice covered with a fish toppings).

Sushi rice is steamed with vinegar and sometimes a little wasabi and sake. Nigiri-zuchi consists of “nigiri” (hand-shaped rectangular balls of rice) and “sushidane” (topping). Often there is a dab of wasabe (hot green mustard) between the nigiri and sushidane.

Typical raw seafood sushi toppings include “akami maguro” (red tuna), “chutoro maguro” (more expensive tuna with more fat), “ohtoro maguro” (even more expensive tuna with even more fat), “aji” (horse mackerel, often topped with chopped scallions and grated ginger), “shima-aji” (yellow jack), “shake” (salmon, sometimes topped with mayonnaise), “ikura” (salmon roe), “isaki” (similar to yellow tail), “ika” (squid), “tako” (octopus), “anago” (conger eel), “unagi” (barbecued eel), “ama ebi” (shrimp), “hotategai” (scallop), and “uni” (sea urchin).

You can also get “hirame” (flounder), “iwashi” (sardine), “ kohada” (gizzard shad), “kuruma-ebi” (prawn), “kazunoko” (herring roe), “geso ika” (cuttlefish tentacles), “mirugai” (horse clam), “akagai” (ark shell), torihai” (cockle), awabi” (abalone), crab, bonito, and sea bream. Sushi restaurants often serve things like “tamagoyaki” (scrambled eggs), ham, seafood salad, raw beef, barbecued meat and even cakes and custard.

Sushi is usually consumed with hot green tea. “Gari” (thin slices of vinegar pickled ginger root) is offered free and eaten between bites to freshen the palate. Two kinds of sauces are usually available: one is soy sauce, which is poured on most kinds of sushi; the other is a thick sweet sauce used on eel. Wasabe (hot, green Japanese horseradish) can be added to make it spicier.

Nigiri-zuchia is typically served two to a plate and eaten in one or two bites. When eating it you can dip the sushi in soy sauce or pour soy sauce on the sushi and lift it to your mouth with chopsticks or with your fingers. See below for information sushi restaurants.

See Separate Articles: BLUEFIN TUNA AND SUSHI factsanddetails.com

BLUEFIN TUNA AND OTHER SPECIES OF TUNA factsanddetails.com ; QUOTAS, OVERFISHING AND DIMINISHING BLUEFIN TUNA STOCKS factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISHING factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISH FARMING factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Sushi and Sashimi, Jewels of Japanese Cuisine rgmjapan.tripod.com/SUSHIINTRO ; Sushi Encyclopedism homepage3.nifty.com ; Sushi Etiquette homepage3.nifty.com ;Sushi World Guide (a global list of over 4,700 restaurants) sushi.infogate.de ; Sueyoshi’s Page on Fish (mostly in Japanese) coara.or.jp/~sueyoshi ; Sushi Otaku sushifaq.com/sushiotaku ; Sashimi Glossary rain.org/~hutch/sashimi ; Sushifaq.com sushifaq.com ; Sushi Links sushilinks.com ; Digital Sushi creativeadornments.com/sushi ; Kaiten Sushi Kaiten Zushi blog.greggman.com/ ;Kaiten Sushi Conveyors cfsystem.it/sushi_conveyors ; Japan Visitor Kaiten Sushi Blog japanvisitor.blogspot.com

Books: “The Sushi Economy” by Sasha Issenberg (Gotham Books, 2007); “The Zen of Fish, The Story of Sushi from Samurai to Supermarket” by Trevor Corson (HarperCaollins, 2007); “The Sushi Experience” by Hiroko Shimbo; “Global Sushi: Soft Power and Hard Realities” by Theodore C. Bestor, a Harvard anthropologist.

Links in this Website: DIET AND EATING HABITS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;JAPANESE FOODS AND DISHES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FOOD SAFETY IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; RICE AND NOODLES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SOYBEANS, SOY SAUCE, NATTO, MISO AND TOFU IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE VEGETABLES, FRUITS AND MUSHROOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE BEEF, MEAT AND DAIRY PRODUCTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SEAFOOD IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SUSHI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FUGU (BLOWFISH) IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; RESTAURANTS AND FAST FOOD IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Sushi

sashimi Freshness is key with sushi. The best sushi is said to be from fish scaled and cleaned right in front of the customers by sushi preparers that like to tell people how to eat it. Some top sushi chefs, though, say that fresh fish is not the best for sushi because it is too hard. Rigor mortis that occurs after death changes the texture of the fish. It is better to let fish stay in a refrigerator for a day to allow it to soften up.

On raw fish, James Bond creator Ian Fleming wrote in 1959, “Only the poor in spirit will refuge to taste sashimi. Only the deficient in taste will refuse to repeat the order.” The idea of cooking a good fish is appalling to most Japanese. "Why would you take this good, fish that cost 7,000 yen a kilo [$36 a pound], and cook it? I mean you kill the flavor! It seem so wasteful," one Japanese man told National Geographic.

From an environmental point of view one is supposed to stay away from yellowtail, octopus and tuna caught with long lines. Squid, king crab and wild salmon are okay. The most eco-friendly sushi is made with farmed scallops, farmed striped bass or sea-urchin roe.

“Makizushi” is the name for a roll containing rice, seaweed, egg and other ingredients rolled together with a special wooden mat and cut into cross sections. Recently it has become popular to make rolls with designs of flowers, pandas and Chinese characters appearing in the cross sections. This is done by strategically placing vegetables and other ingredients with desired colors in the rice so when the makizushi is rolled up and cross sections are cut the designs appear. The Sammu area of Chiba Prefecture is famous for the skill. Here women can make about 200 designs, including plum blossom and cherry blossoms.

See Restaurants

History of Sushi

Many people sushi think must have been around since time immortal in Japan — according to some sources sushi originated in China and came to Japan in the 8th century — but it was in fact was invented around 1850 years by Tokyo street vendors as a snack.

Sushi began as a way to preserve fish at a time when there was no refrigeration. The fish was wrapped in rice and allowed to ferment slowly and when the process was over the rice was thrown away. In the old days in China and Japan, people salted fish and mixed it rice and left it to ferment, sometimes as long as three years.

types of sushi

The nigiri-zushi (modern sushi) developed in the Edo period (1603-1867) didn't contain salt. It was tasty, nutrition and cheap and became a staple of Tokyo's poor. Sushi didn't really catch on nationwide until the 1950s when transportation and refrigeration made it possible.

The globalization of sushi took place in the early 1970s with advent of long-distance air cargo. Refrigerated planes used by Japan Airlines, which were flying fully-loaded to North America and returning home empty, were set up to carry tuna, long regarded as a trash fish, back to Japan. Fisherman began taking interest in the scheme when the average price paid to them for Atlantic tuna jumped from 11 cents a pound in 1972 to 42 cents in 1973 and reached $1 a pound in 1978.

In the Bubble-Economy era of the 1980s, when prized fish began commanding prices in the tens of thousands of dollars in Japan and and people in Tokyo ate sushi with gold flake sprinkled on top, American fishermen began making huge profits by selling the fish by consignment rather than handing them over to middlemen. A gold rush mentality led to overfishing and near collapse of some tuna fisheries.

By the 1990s sushi had become an international phenomena. At that time the world's largest sushi roll (127 meters long) was produced at a department store in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. The 160-kg roll was made with rice, cucumber, shredded pork and seaweed. In 1995, 211 Japanese tourists in Bali came down with cholera from eating raw fish.

Internationalization of Sushi

Thanksgiving sushi with

turkey and cranberry sauce In recent years sushi has become very popular in North America and Europe. Trendy restaurants in Los Angeles serve things like dragon rolls. (rice shaped like a snake and garnished with broiled eel that represent dragon scales), spider rolls (fried softshell crab meat wrapped in rice with crab legs sprouting out the top like legs of a spider), California roles (rice with fake crabmeat, cucumber and avocado), and caterpillar rolls (rice covered with carrots and avocado and shaped like a caterpillar). A Hot tuna roll features pounded tuna spiced with chili sauce. A crunchy roll has pieces of deep-friend tempura inside. In Belgium you can get hand-rolled sushi topped with chocolate sauce. In Russia you can get borscht sushi consisting of vinegared rice mixed with borsht and rolled up in nori.

At restaurants in New York you can get tuna sashimi with green apple sauce with lime and wasabi. At Mariners baseball games in Seattle you can get Ichi-rolls anmed after the famous Japanese ball player. In Sao Paulo there are now more sushi restaurants than Brazilian barbecues. Sushi restaurants are also very popular in London, Moscow and Dubai.

Some non-Japanese variation such as sushi with cream cheese and flying fish roe or sushi rolls with avocado, salmon eggs, cucumber and red chilies that were popular in New York, and Los and have been packaged for Japan and found a receptive audience in Tokyo and other Japanese cities.

In January 2011, the All-Japan Sushi Federation launched a certification program aimed at teaching proper technique and hygiene to foreign sushi chefs such as how to preserve raw fish, washing the chopping block after each use and basic knowledge on antimicrobial benefits of vinegar and wasabi.

Bluefin Tuna Sushi

plastic toro Bluefin tuna is regarded as the premier sushi fish. One restaurant owner in Tokyo told the Washington Post, Tuna is “the” sushi in a sushi restaurant. If you have good tuna, you have a reputation of being a proper restaurant.” A single bite of meat from the belly of this fish can cost $40 in a sushi bar. Virtually all the bluefin tuna in Japan is eaten raw and people from different parts of Japan have different preferences. In Kyoto people reportedly like reddish bluefin tuna meat; in Yokohama, pink; Osaka, oily; and Tokyo, bright red. [Source: T.R. Reid, National Geographic. November 1995]

Bluefin is the most valuable fish in the world. The most expensive sushi is made with fatty meat, know as “toro”, from the belly. The rest of the fish is called “maguro”. Skipjack, yellowfin, albacore and big eye tuna are generally worth 10 to 15 times less than bluefin. Generally tuna found in can is made from one of these fish. The best toro is pinkish, orange in color Sushi restaurants can purchase a special oil that can be applied to cheap, dark red toro so pass of it off as expensive toro.

Adam Yamaguchi and Zach Slobig wrote in the Los Angeles Times: "Otoro" (fatty tuna) is the filet mignon of sushi. Atop a small mound of rice, a heavily marbled slice of fish sits precariously “ so oily that it's on the verge of falling apart. With one bite, the exquisite cut of bluefin will melt into oblivion. Bluefin tuna may not be a household name, but its taste and texture are famous “ and increasingly infamous “ among sushi aficionados across the world. Hailed as the finest cut of tuna sashimi, the oily, fatty belly of the bluefin has also found its way onto many do-not-eat lists among consumers and environmentalists because the fish's numbers have plummeted in recent years. [Source: Adam Yamaguchi and Zach Slobig, Los Angeles Times, July 21, 2011]

One long-time Japanese resident told National Geographic, "Fresh bluefin at the peak of autumnal fattening, cut paper-thin and eaten raw, provides an experience for which the Japanese have a vocabulary of distinctions as exquisite as that of the French for Bordeaux wines." Bluefin tuna hasn’t always been popular. In the Edo Period many Japanese regarded it as too greasy and often threw away the fatty “toro”portion.

Explaining the finer points of bluefin tuna buying, Hiroyasu Itoh, a buyer for a famous fish wholesaler, told National Geographic: "Why is that Americans think any fish is just like every other fish. They're not made in a factory, you know. It seems perfectly obvious to us that a bluefin from the cold, rough seas around Tasmania will have a different meat than a bluefin from tropical waters. I guess if you cook your tuna with lemon and seasoning, then it all starts to taste the same. But's that another thing I can't understand." [Source: , T.R. Reid, National Geographic]

Salmon and Sea Urchin in Japan

Salmon sushi is very popular. It is often served with mayonnaise and onions top. Salmon breeds in rivers in northern Niigata Prefecture, the Tohuku region and Hokkaido. The fish from the Murakami area of Niigata is regarded as the best. Many sushi chefs say that male salmon tastes better than females.

The Japanese word “ikura” (“salmon eggs”) comes the Russian word “ikrra” (“cavair”). Ikuri sushi is a favorite with Japanese children.

Uni (sea urchin meat) is a popular delicacy in Japan. It is soft, buttery and yellow, red or bright orange in color. To eat it you break open the shell and pick out the sexual organs with your chop stick, dip it in some soy sauce and swallow. In uni-producing areas it is often served in a bowl of rice.

Store-bought uni melts in the mouth. Fresh uni is firm and the texture of each tiny egg can be felt. Uni is best eaten in the summer when the sea creatures fatten themselves up before spawning in the autumn. The best quality stuff is preserved in salt water and is often served with seafood jelly

There are 10 uni-producing regions in Japan. The uni from each region being a little different. The west coast of Hokkaido is the main uni-producing area in Japan. Much of the sea urchin sold in Japan comes from California, Oregon and Maine. Sea urchin supplies have been so badly depleted in Japan that uni fishermen are only allowed to fish in Japanese waters two hours a day.

Some domestically-produced sea urchin comes from Miyagi Prefecture. Some measure 15 centimeters across and are said to be at their best when they are harvested in June. Boats set out at 5:00am and fishermen search for the sea creatures using wooden boxes with glass bottoms, Fishermen use poles, which have hook on the front edge, to pick up and drop sea urchins in a basket under the water. The uni harvesting season lasts from June to August.

Eel in Japan

See Seafood section

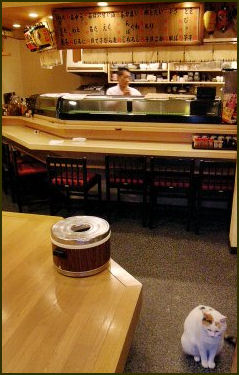

Sushi Restaurants in Japan

There are around 45,000 sushi restaurants in Japan. These include “sushiyas” (regular sushi restaurants) sushi bars, “kaiten-sushi” (conveyor belt sushi restaurants) and sushi delivery services. Together they employ around 220,000 people.

“Sushiyas” (sushi restaurants) are generally expensive. Some are bars. Some are sit down restaurants. Some are both. Customers can choose small plates with two pieces of sushi (make sure to determine whether the roie is a single sushi or plat of two sushis) or plates with a half dozen or a dozen different sushis.

When at a restaurant you can simply order by pointing you fingers. Palate-freshening ginger water and tea are offered for free. In Japan, many people like to drink beer with sushi. Be careful. Eating at a regular sushi restaurants can be very expensive.

Relatively inexpensive sushi can be purchased at “kaitenzushi” (conveyor-belt sushi restaurants), in which plates of sushi move past customers on conveyor belts and customers grab what they want. See Below

Meals at the finest sushi restaurants can cost $300 per person. The seafood is usually amazingly fresh. Describing preparation of fresh shrimp sushi, Jerry Hopkins, author of “Strange Food: Bush Meat, Bats and Butterflies” told the Washington Post, "The sushi chef reached into an aquarium, pulled out a live shrimp, peeled it and plopped it on a lump of rice. He then squeezed lime over it, causing the shrimp to wriggle and writhe in what appeared to be discomfort. It was at that point you were supposed to put it your moth."

Describing the sushi he had at Kachidoki Sishidai Bekkan behind Tsukiji fish market, Ben MacIntyre Wrote in the Times of London, “I have eaten quite a lot of sushi in may time...But I have never eaten sushi as fresh and delicious and unidentifiable as we ate in this, each dish a perfect little concoction. One after another the dishes came as beautiful as they were delicious.”

Kaiten Sushi

Kaiten sushi restaurants (conveyor belt sushi restaurants) are very popular with foreign tourists as they are with Japanese. Plates of sushi move past customers on conveyor belts and customers choose what they want. Each plate has two pieces of sushi and is color coded according price. Thing like squid and cheap cuts of tuna go for as little as ¥100 yen while expensive cuts of tuna, abalone, sea urchin, salmon roe and eel go for ¥300 or ¥500 a plate. The price of the meal is determined by counting up the plates.

Eating at a kaiten sushi restaurants is interesting and entertaining. You have to think quickly and make snap decision: should I take this one or wait for the possibility of something better to come down the pike? If you don't like what is being served you can special order what you want.

About 4,000 kaiten sushi restaurants operate nationwide, including 305 Kappa Sushi restaurants, with industry-wide annual sales of around $5 billion. Cheap sushi operations owe their existence low-priced imported seafood which cost considerably less than domestically-caught seafood. These imports include farmed Atlantic salmon, whose fatty taste and orange color is said to appeal to women, octopus from Morocco, shrimp from Southeast Asia and sea urchin from South America.

The first kaiten-sushi restaurant opened in Fuse, now Higashi in Osaka in 1958. The operator, Yoshiaki Shiraishi, equipped a counter at his sushi restaurant with a revolving belt after seeing a conveyor belt carrying bottles at an Asahi beer factory and thinking he could reduce the work of his waiters with such a devise. At that time a plate of four sushi pieces sold for ¥50.

Kaiten-sushi restaurants including low quality one in which everything is ¥100 and gourmet versions in which most offerings are more than ¥500, including ¥690 maguro and ¥860 horse mackerel pulled from a tank in front of the customer’s eyes. Some also serve cakes, Chinese food, rice balls and other finger food. Some allow to eat all you want for one hour for around ¥1,500.

Kura Moving Sushi Restaurants

Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in the New York Times, “The Kura “revolving sushi” restaurant chain has no Michelin stars, but it has succeeded where many of Japan’s more celebrated eateries fall short: turning a profit in a punishing economy. Along with other low-cost restaurant chains, Kura has bucked the dining-out slump with low prices and a dogged pursuit of efficiency. In the company’s most recent fiscal year, which ended in October 2010, net profit jumped 20 percent from the same period a year earlier, to 2.8 billion yen. [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, December 30, 2010]

“At a Kura, a sushi plate goes for 100 yen, or about $1.22. Such measures are helping Kura stay afloat even though the country’s once-profligate diners have tightened their belts in response to two decades of little economic growth and stagnant wages.”

Kura was launched in the depths of the slump, in 1995, by Kunihiko Tanaka, Kura’s current chief executive, whose goal was to serve quality sushi on the cheap. Tabuchi wrote; “His idea of using conveyor belts to offer diners a steady stream of sushi on small plates was not a new one; an Osaka-based entrepreneur invented such a system in the late 1950s. But Mr. Tanaka set out to undercut his rivals with deft automation, an investment in information technology, some creativity and an almost extreme devotion to cost-efficiency. In Japan, where labor costs are high, that meant running his restaurants with as few workers as possible.

“Its not just about efficiency,” Takeshi Hattori, Kura’s company spokesman told the New York Times. “Diners love it too. For example, women say they like clearing finished plates right away, so others can’t see how much they’ve eaten.” “It’s such a bargain at 100 yen,” said Toshiyuki Arai, a delivery company worker dining at a Kura restaurant with his sister and her 3-year-old son.

Traditional sushi chefs have not fared so well, however. While the overall market for belt-conveyor sushi restaurants jumped 42 percent, to 428 billion yen, in 2009 compared with 2003, higher-end sushi restaurants are on the decline, according to Fuji-Keizai, a market research firm. “A real sushi restaurant?” Arai said. “I hardly go anymore.”

Moving Sushi Restaurant Automation

“Efficiency is paramount at Kura: absent are the traditional sushi chefs and their painstaking attention to detail,” Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in the New York Times. “In their place are sushi-making robots and an emphasis on efficiency. Absent, too, are flocks of waiters They have been largely replaced by conveyors belts that carry sushi to diners and remote managers who monitor Kura’s 262 restaurants from three control centers across Japan. (“We see gaps of over a meter between your sushi plates “ please fix,” a manager said recently by telephone to a Kura restaurant 10 miles away.) Instead of placing supervisors at each restaurant, Kura set up central control centers with video links to the stores. At these centers, a small group of managers watch for everything from wayward tuna slices to outdated posters on restaurant walls.” [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, December 30, 2010]

“Each Kura store is also highly automated ,” Tabuchi wrote. “Diners use a touch panel to order soup and other side dishes, which are delivered to tables on special express conveyor belts. In the kitchen, a robot busily makes the rice morsels for a server to top with cuts of fish that have been shipped from a central processing plant, where workers are trained to slice tuna and mackerel accurately down to the gram.”

“Diners are asked to slide finished plates into a tableside bay, where they are automatically counted to calculate the bill, doused in cleaning fluid and flushed back to the kitchen on a stream of water. Matrix codes on the backs of plates keep track of how long a sushi portion has been circulating on conveyor belts; a small robotic arm disposes of any that have been out too long... Kura spends 10 million yen to fit each new restaurant with the latest automation systems, an investment it says pays off in labor cost savings. In all, just six servers and a minimal kitchen staff can service a restaurant seating 196 people.”

Sushi Chefs in Japan

David Jolly wrote in the New York Times, "Budding sushi chefs must go through a long apprenticeship to become masters, enduring the drudgery of washing dishes, preparing rice and cutting vegetables before they even begin to start cutting fish. Only in the fifth year do they begin slicing fish in earnest."

In their seventh year, the apprentices graduate to serving and conversing with customers. That’s the same length of time it takes to both earn a bachelor’s degree and graduate from medical school. With qualifications like these, sushi might have stayed in Japan.

Top rated sushi chefs are known as “itamae” ("chef") and “shokunin” (literally "artisan"). Makato Kosugi, head of one of Tokyo's most famous sushi restaurants told the Los Angeles Times, "It takes 10 years, at the very least, to learn all the facts of becoming a chef, and 10 more to be able to do it in front of customers...From my point of view, becoming a chef without the proper and lengthy training as an apprentice — without the proper foundation — is a bad idea."

Mamoru Sugiyama is the sushi chef at Sushiko in Tokyo, a Michelin-starred restaurant that dates back to the 19th century. He and other sushi chefs say sushi preparation is much more difficult than it looks. You have to know when fish are in season and under what conditions they taste best. And you have to also know the special cuts, preparations methods and what kind of rice to use with each fish.

These days the sushi preparation trade is changing. Low-end restaurants often hire high school kid s who prepare the sushi in almost assembly line fashion.

The vast majority of sushi chefs have traditionally been men. This is because it has been said that the women wear too much potentially-contaminating perfume and make-up and their hands are too small and warm.

Automated Sushi Chefs

The Suzomo Machinery Company has developed an $86,000 sushi-making machine with four pairs of white plastic hands that turn out 1,200 rectangular pieces of sushi every hour for sale in fast food restaurants and supermarkets. "The hands pat the rice once, twice," writes Elaine Louie in the New York Times," Pat, pat. Wasabi, a horseradish sauce, drizzles from a tube onto the rice. Kimiche, ueki, a sushi chef, places the fish on the rice, and the plastic hands pat the rice again. the whole process takes three seconds."

A sushi chef on average can only make about 200 to 300 pieces of sushi an hour. Machine-made sushi sells for between 50 and 70 cents a piece, while human-made sushi costs $1.50 a piece or more.

Sushi Chefs and Knives

plastic sushi A sushi chefs most prized possessions are his knives. During special ceremonies at some food school chefs don white kimonos and wave their knives in a prescribed manner over a special cutting boards with a piece of sea bream when they graduate from the school

One sushi chef, with 18 years experience, said it takes ten years to learn how to make sushi properly and the key is, "It must be fresh!" When asked what he did when he cut himself, he replied, "I squirt the cut with Krazy Glue, blow on it and keep on slicing."

There are special knives for specific tasks. A broad, heavy blade is used gut and filet a fish. Big knives with square edges are used in fish markets to cut tuna. A tiny knife called a “aj-kiri” is used for cutting sardines. There is even a special knife called a “hamo-kiri” that is used to filet eel.

The knives used to cut sushi, like most Japan knives, are sharpened on just one side. This makes for a cleaner cut and doesn't affect the texture of the fish — which many Japanese say affects the taste — as much as knives sharpened on both sides. The main problem with the Japanese knives is they require repeated sharpening, often once a day on a stone, which requires more effort than on a Western-style sharpening stick.

Tokifusa Iizuka, from Sanjo City, is regarded as Japan's finest knifemaker. Selling for between $250 and $1,500, the knives are prized specialty by sushi chefs and made the same way as samurai swords with repeated pounding and folding. With handles made of wood and buffalo horn, they are so sharp they can slice an onion into nearly transparent, paper thin slices with cuts that are so clean that no tear-producing spray is produced.

Describing Iizuka at work, Valerie Reitman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, "Holding the red-hot metal with a pair of giant clippers, he folds it again and again, pounding it with a wooden mallet to create the blade's shape...Once the blade is cool, he begins the series of steps to grade and polish it, including attaching it to a rudimentary device, known as a “sen”, which looks like a clothespin turned on its side and manually shaving it with a razor attached to a cross-shaped device.”

"In the final stages, he puts the blade on sharpening stones and files away until they are smooth, occasionally dipping the knife in a gutter of green nitric acid that prevents rusting." Iizuka said he bought a $100,000 blade smoothing machine but discarded it because his skill was great than the machine.

Sushi Apprentices

Traditionally sushi chefs began their careers after middle school by serving as apprentices for more than a decade before becoming chefs. The first years are spent collecting plates, washing dishes, making deliveries and cleaning floors and toilets. As newcomers arrive they begin to work their way up.

As they advance sushi apprentices learn how to mold the rice and cut the fish. Finally they learn how to chose fish at the markets and make unique concoctions with the high grades of tuna, abalone and sea urchin. There is no licensing exam.

In the old days, sushi apprentices were paid nothing, worked every day of the year except New Year's and slept inside the restaurant. Sushi masters are notorious for hitting apprentices who can't get it right. Recalling his teach when he was apprentice, one sushi master told the Los Angeles Times, "He was like the Emperor or God."

Sushi University offers a 12-month course or a one-month, nine-hours a day crash course for $15,000 to $17,500. Students study under 80-something sushi master Katsuji Konakai, who has been in the sushi trade since he was 14. The "university" consists of two rooms filled with refrigerators, lockers, tables and large rice cookers.

Sushi Restaurants Abroad

sushi wedding cake Nigiri (hand-molded sushi rice topped with pieces of fish) was first introduced to California in the 1960s but didn’t catch in among the locals until local chefs came up with their own concoctions: namely the California roll made with avocado, crab meat and cucumber. The first California rolls had nori (sea weed) on the outside but over time where turned inside out so the nori was on the inside. On survey found that 40 percent of American that say they love sushi in fact like sushi rolls, not nigiri.

David Jolly wrote in the New York Times, “In the greater Paris region, where I live and work, there are more than 1,600 sushi restaurants. They are springing up faster than can be counted in Eastern Europe, India and China, not to mention Los Angeles and New York. Yet the authenticity of many of them is dubious. Some were transformed from cheap Chinese restaurants to cheap Japanese restaurants with the aid of kits and machines provided by helpful industry vendors; others belong to the growing number of fast-food-style sushi franchises. All are in the business of selling fish and vinegared rice.” [Source: David Jolly, New York Times, June 20, 2011]

The internationalization of sushi turning point, according to “ a 2010 French television documentary the “World Sushi: Dead Oceans Ahead” — was the rise of California sushi, and in particular the phenomenal career of the celebrity chef Nobuyuki Matsuhisa. Mr. Matsuhisa was born in Saitama Prefecture in Japan and opened his breakthrough Beverly Hills restaurant in 1987, and sushi quickly acquired a certain chic. He went on to build a Nobu empire that stretches from the West Coast to New York, Melbourne, London, Hong Kong, Mykonos and Milan.

Sushi restaurants began making their presence known in the United States in the 1980s and quickly caught on and became the restaurants of choice among yuppies. On the West coast you can find sushi restaurant in baseball stadiums. One place in New York sells raw yellowtail with jalepeño peppers and rice balls served with catsup. Another offers rolls made with fried calamari, sweet potato, and cream cheese. Miami rolls served in Florida are made with salmon and cream cheese. A Japanese sushi chef in Texas makes “Longhorn rolls” with rib-eye steak, cream cheese and avocado, served with a green sauce made of cilantro and jalapeño. Other places serve up varieties with beef and nuts. Sushi rolls sold at American supermarkets are typically made with salmon, fake crab, tuna and avocado.

The U.S. has made sushi-making more time efficient and standardized. Seven years of training for sushi chefs ahs been condensed to three months or even less, as Trevor Corson notes in “The Story of Sushi.”In Los Angeles many sushi restaurants are run by Koreans or other non-Japanese. In New York many are run by Indonesian-born Chinese. Many American sushi chefs are trained in the United States. Many spend two or three years in a Japanese-run sushi shop and saveup money to open restaurants of their own.

Imaginative New York Sushi Restaurant

Sushi Uo is a New York sushi bar opened in 2009 by 23-year-old David Bouhadana, who grew up in Florida, of French and Moroccan parentage, and spent five years apprenticing with various sushi masters in the States and in Japan before launching Sushi Uo, his first restaurant, up an unmarked flight of stairs on the Lower East Side. Describing the food Leo Carey wrote in The New Yorker, “ The menu features both traditional sushi and more inflected dishes, some of which don’t avoid the vagaries of Asian fusion. Salmon skin — rich, fatty, cooked almost to the consistency of pork rind — worked quite well with wasabi gnocchi, though without convincing you that Italian and Japanese cuisines ought to get together more often. (On another night, the skin made a satisfying combination with a salad of arugula, apple, and pine nuts.) [Source: Leo Carey, The New Yorker, January 4, 2010]

“One inventive dish is a so-called tartare, consisting of edamame chopped with shiso and citrus. Carey wrote. “The preparation foregrounds the beans’ nutty flavor, and is an antidote to all the edamame that one has sucked from salty pods without ever really tasting. Ultimately, though, you sense that unadulterated sushi is Bouhadana’s real interest. His restaurant doesn’t provide the almost intimidating flawlessness of the best midtown sushi temples, but its food’s quality is consistently higher than that of almost any comparably priced establishment and far removed from that of ordinary neighborhood joints, with their cloudy hunks of tuna and cardboardlike eel. Here, tuna is a brilliant, clear red, like stained glass, and eel is soft and pliant. Bouhadana makes subtle tastes register — like the Japanese citron that he zests in microscopic quantities over live scallops — and his presentation is deft: the body of a mackerel, its meat filleted into neat rectangles, is bent back with a bamboo skewer, as if turning in the water.”

“Barking out instructions in Japanese, Bouhadana works with just one sushi assistant and one cook. This probably helps keep prices down, though when the restaurant is full you fear for his sanity, and his fingers. On calmer nights, he holds court for whoever is at the sushi bar, explaining the difficulties of sourcing ingredients, or why he finds mackerel more interesting than tuna belly, or why, when preparing live orange clams, one must not only cut them into strips but fling each piece down dramatically on the counter, where it visibly recoils on impact. Apparently, the jolt causes the muscle fibres, still alive, to tense, giving the clam a new texture, sinewy and strange. (Dishes $4-$15.50; sushi $3-$46.)

Documentaries About Sushi and Overfishing

The documentary “Sushi: The Global Catch” won a special jury prize in June 2011 at the Seattle International Film Festival. It’s director Mark S. Hall first sampled sushi as a student in Tokyo in the 1980s, but he did not get to thinking about the sushi economy he was in Poland. “I was working in Warsaw as part of a cooperative that was building a pretty interesting organic agriculture business,” Mr. Hall told the New York Times. “We were at a meeting, and when we broke for lunch I assumed we’d go for bigos [a kind of cabbage stew] or sausages. Instead we went for sushi. I got to wondering how, in a culture where they hadn’t known it even a few years before, it had gotten so popular. And it wasn’t the same, it really wasn’t anything like the experience I’d had in Tokyo. It just floored me.” [Source: David Jolly, New York Times, June 20, 2011]

French television documentary “World Sushi: Dead Oceans Ahead” was released in 2010. David Jolly wrote in the New York Times, "Both documentaries begin with segments on restaurant, history and chefs and then shift abruptly from the sushi tale to the conservation story, with the narrative alternating between those who are hoping that informed consumers can help to rescue the seas by eating only “sustainable” sushi, and those who believe in untrammeled fishing regardless of the costs. “I thought it was very important that people understood the unintended consequences that globalization was having on endangered fish,” Mr. Hall said.

Like “The End of the Line,” , a 2009 documentary by the investigative reporter Charles Clover, “World Sushi: Dead Oceans Ahead (whose original French subtitle read “Tomorrow, Our Children Will Eat Jellyfish”) is an excellent primer on the problems caused by overfishing, Jolly wrote. It looks at the workings of the international fish trade through a wide geographical lens, including fishermen and markets in Japan, the Mediterranean, Senegal, Peru and the United States. One of the most telling moments in the film comes as the crew follows Mr. Matsuhisa to a fish market and asks him about the ethics of serving bluefin in his restaurants. “Nobody knows about 50 years later,” he replies. “I buy the fish from the fish company, the fish company has a license to buy the tuna. Then why does Greenpeace attack us?” Then he suggests a change in subject.

Interestingly, both Mr. Hall and Mr. Canet said that when they began their projects, they planned to focus on sushi and its rise to world food status, but then found that the environmental issues turned out to be the more important story. “Instead of the original project I’d imagined on the tradition and consumption of sushi with a little discussion of the environmental issues, I realized I had it backwards. So I refocused on the environmental issues, with overfishing being the most urgent topic,” Mr. Canet said.

“I like sushi “ I’m not the Taliban,” he said. “But we have to do it a lot more intelligently than we are currently. We have to change the mindset that sees wild fish as a commodity like wheat or corn. It’s impossible to imagine that the system we have now can continue.” Mr. Hall noted that the prospects for some fish, especially those at the top of the food chain, do not appear to be good. He said he hoped that consumer education would help.”I’m probably more optimistic than I should be,” he said. “Maybe that means I’m naïve. But I think doing something is better than doing nothing.”

Image Sources: 1) Kanazawa City Tourism Promotion 2) 7), JNTO; 3) 5) 10); Goods from Japan; 4), 9), 11) xorsyst blog 6) Japan Zone 8) Ray Kinnane

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013