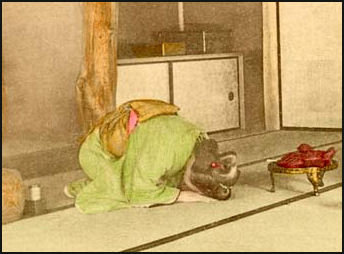

JAPANESE SHYNESS

A deep bow to welcome a guest

in the 19th century The Japanese are notoriously shy and private and are regarded as much more reserved than Koreans or Chinese. Privacy is important in Japan. People can have their names removed from phone books if they want. Windows are designed so people can't look in. Asking a lot of question is regarded as pushy and rude. People are often expected to be quiet.

Many school children have said they have never seen their parents kiss. Young adults don’t talk about their boyfriend or girlfriend or lack of one and generally don’t like to be asked questions about their private life. In one survey Japanese university students said they considered a good friend to be someone who respects their private life. Television drama plots often revolve around romances that others figure out from a few clues.

Japanese generally don’t like to stick out in public or talk to strangers unless there is some necessity to do so. Many Japanese are very shy about meeting with foreigners. They feel embarrassed if they make mistakes speaking English, and thus avoid saying anything. They also feel a lot of stress if they perceive the foreigners as being aggressive or pushy.

Dog owners often find pets are an easy way to meet new people. They often talk to one another through their dogs by asking questions directed toward the pet not the owner. “Koen debut” is a term used to describe the stressful first visit for a mother and child or for a dog owner and pet to a new park. To make the process go smoothly many pet owners have business cards with pictures of there dogs printed up. A common icebreaking expression is saying how “kawaii” (“cute”) a person’s dog is.

The owner of a dog named Moko told the Asahi Shimbun, “My son didn’t go to a local school, so for a long time we had no friends here. If it weren’t for Moko, we wouldn’t have met our dog-owner friends...Relationships in the big city can be cold and distant. But when dogs socialize with each other, it helps break the ice among dog owners.” She then explained that is why so many people with dogs visit the local park.

Pico Iyer, a writer who has lived in Japan for more than 20 years, said there is passionate reverse side to Japanese restraint. He wrote: “The people I know in Japan are extraordinarily intense and devoted to their passions precisely because they tend to be Self-denying and restrained in public.”

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: JAPANESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE POLITENESS AND INDIRECTNESS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SOCIAL LIFE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SOCIETY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE REGIONAL DIFFERENCES Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Journal of Personality by the Japanese Society of Personality jstage.jst.go.jp ; Japanese Society and Culture in Perspective habri.co.uk ; Japanese Culture, a Primer for Newcomers thejapanfaq.com ;Traditional Japan, Key Aspects of Japan japanlink.co ; ACE Japan , Japan Association for Cultural Exchange acejapan.or.jp ; Opinion on Asian Fetish colorq.org ; What Japan Thinks, a blog with info on demographics and statistics whatjapanthinks.com

Academic Articles Gender-Role Personality Traits in Japanese Culture pdf file mwsu.edu/sociology ; Advise Giving and Personality Traits of Japanese University Students jalt.org/pansig ; Confucianism, Personality Traits and Leadership in Japan pdf file psychology.csusb.edu ; Blood Types and Personality Japan Visitor on Blood Types japanvisitor.com ; Blood Types and Personality issendai.com ; Academic Paper on Blood Types and Personality sciencedirect.com

Books Classic books on the Japanese character and society include “The Chrysanthemum and Sword” by Ruth Benedict, “Vertical Society” by Chie Nakane, and “Bushido” by Inazo Nitobe. Among the more recent books on these subjects are “Japan’s Cultural Code Word: 233 Key Terms That Explain the Attitudes and Behavior of the Japanese” by Boye Lafayette De Mente (Tuttle, 2004) and “Japanese Patterns of Behavior” by Takie Sugiyama Lebra. Sites for Expats Japanable site for Expats japanable.com ; That’s Japan thats-japan.com ; Orient Expat Japan orientexpat.com/japan-expat ; Kimi Information Center kimiwillbe.com ; Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report on Japan fco.gov.uk/en/travel-and-living-abroad ; Student Guide to Japan www2.jasso.go.jp/study ; Japan in Your Palm japaninyourpalm.com

Japanese Sense of Privacy

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “There is no traditional Japanese word for privacy, and as a result, the English word is used to refer to it. Because of this, people sometimes suggest that the concept privacy did not exist in Japan traditionally. However, as ethics scholars Masahiko Mizutani, James Dorsey and James Moor demonstrate, the notion of privacy has long existed in Japan. The researchers give a nice example of the use of “ shimenawa “, a straw rope used in Shinto shrines to designate sacred, and therefore private, areas. Physically it was possible to walk through, but the rope was respected as a symbolic indication of an area that should not be entered. Additionally, there are Japanese words such as himitsu (secret) that correspond to types of privacy. Mizutani, Dorsey and Moor further assert that most, and perhaps all, of the six senses of privacy listed in the Oxford English Dictionary can be expressed in traditional Japanese words. There just wasn't one nifty word to cover it all.[Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, November 2, 2010]

“Privacy in the form of the "right to be left alone" is clearly practiced in Japan. But on top of this, from an American perspective it can sometimes seem as if personal privacy is closely guarded through a practice of nondisclosure of any nonessential information. Some years ago, an American man, who I'll call Andy, and I worked together with a Japanese man, let's call him Takeda-sensei, on a project for three years. About halfway through the second year, Takeda-sensei casually mentioned that his wife had had a baby. His announcement was so low-key that I almost missed it, and when my American colleague realized it, he was more than surprised; he was hurt and angry. We had met with Takeda-sensei once a week for more than a year and had worked together closely during those sessions. Andy couldn't believe that the man had never once mentioned his wife was pregnant. He viewed the concealment of such a major life event as a slap in the face of the friendship he had supposed he had shared with our Japanese coworker.”

“But while the onus is strong in American friendships to notify others of important life events, the relative flimsiness of this burden in Japan can conversely make it difficult for Japanese people to know when exactly to bring up such matters. Many Japanese people have told me that they were not averse to some personal details being known by friends, but they just didn't find the right timing for the announcement. The equivalent of "Guess what?"”Ne, ne!”is only used in very close relationships. Many instead wait for the "Jitsu wa... (Actually...)" moment: a question, often innocuous, asked of them for which truthfulness demands revelation.”

In Japan it is also common when three people meet and two don’t know each for there to be no effort to introduce the two who don’t know each other. On top of that if two of the people are engaged in quick chat it is regarded as polite for the third person a retreat a little, allowing the other two some privacy. Elwood said: “In Japan, in many situations, the default position is one of discretion, while American standard operating procedure dictates openness bar any compelling grounds for reticence.”

Kejime, Drawing the Line

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Educational anthropologist Joseph Tobin has argued that kejime, which he defines as "correctly reading the context for what it is and acting accordingly" is the key to child socialization in Japan. At the nursery school level, contexts include the physical environments of home and school as well as situational points of view and demeanor while engaging in various kiddy activities, like running around, eating lunch, drawing pictures, and singing songs.” [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, April 26, 2010]

Elwood views kejime as akin to “drawing the line.” “While American children may learn "a place for everything and everything in its place" with coat pegs and cubbyholes,” she wrote, “their Japanese counterparts additionally begin training in the mental pegs and psychological compartments associated with varying circumstances. While there are few clearly defined margins between American preschool pursuits, and one activity often casually slides into the next, with some stragglers making the switch between modes more slowly, Tobin, based on ethnographic observation, asserts that Japanese preschools deliberately plan and execute clear-cut events throughout the day in order to train children to move appropriately from one mindset to the next. Kejime is most often used in the phrase kejime o tsukeru — distinctions are marked. Boundary lines are drawn, attitudinally and behaviorally. Toddlers are encouraged to recognize these territories and shift efficiently between them, developing an internal on-off switch.”

“After reading Tobin's assertion, I garnered the opinions and insights of a range of Japanese acquaintances, who agreed to the notion of kindergarten kejime-fication. They noted that its development is even more explicit in primary school. Kejime is a word that is quick on the lips of teachers, and often parents. One fifth grader mentioned that the first thing her teacher said when the new school year began this month was "Kejime o tsukete, yaru toki wa yaru, asobu toki wa asobu (Make the distinction: when it's time to do something, you do it. When it's time to play, you play.)."

“Naturally American teachers and parents also hope that children will learn to focus on a given activity and not, for example, run around the table rather than sitting properly at mealtimes. But the teaching of the importance of making a thorough transfer of attention and conduct is less explicit. The point Japanese teachers are making is not that study should take precedence over play, but rather that each is important yet they need to be understood as wholly discrete activities.”

“Among adults, kejime is often associated with making the distinction between public and private: “ koshi no kejime o tsukeru “. The two realms of life are understood to be properly marked as separate spheres, and any mingling is carefully orchestrated. While Americans may feel that it is not good to bring the office home, talking shop at parties on weekends is still common. Similarly, it is generally more common for an American office worker to bring a spouse or children in for a visit to the workplace. Public and private are more likely to be perceived as different points on a continuum with no firm line drawn between them.”

“Americans lack early-age kejime training because kejime itself is a less important cultural value. In contrast, "social chameleons" who change their color exceedingly or abruptly may be viewed with mistrust. Many comedic sequences are based on the idea of a person who undergoes unexpected alteration depending on the situation. So, too, are some rather more serious dramatic plots sequences, when a character discovers a person he or she thought they knew well behaving quite differently. We are comfortable with gradual or muted adjustments according to circumstance, with a segue, not the type of complete switch represented by kejime.”

“Another type of kejime is not a back and forth shifting but rather a total commitment. This is the kejime of Masahiko Kondo's 1984 hit song Kejime-nasai, calling for a lover's romantic unswerving dedication. In another, more violent, form, it is the kejime of yakuza movies. In these manifestations of the term, a line is drawn, and once crossed you don't go back. Similarly, kejime is used generally to express the need to distinguish between right and wrong, and to adhere firmly to the path of virtue. At other times, kejime can be used regarding a single, resolute shift. When I asked one informant to tell me her image of kejime, she described a student studying for university entrance exams. The student makes his or her choice of what exams to sit for, studies assiduously, and then when it's over, it's over, regardless of outcome. The transfer is made from working wholeheartedly to influence a result to unconditional acceptance of the outcome. In this sense, kejime is the positive flipside of akirame, or giving up.”

Traditionally, the U.S. has been seen as a melting pot of cultures. Some have challenged this image, asserting the salad-bowl theory of pluralism. Perhaps for Japan an obento theory works best — various tasty cultural elements, neatly and elegantly apportioned.”

Uncertainty Avoidance in Japan

Sometimes for informal get-togethers Japanese provide detailed information on who will be there, the date and time, venue, address, telephone number. Some Japanese find this style a bit formal or businesslike but ultimately practical, while some Americans find it a bit off-putting, preferring a more amiable style. Some cultural anthropologists view the formal Japanese style as an example of "uncertainty avoidance." [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, August 27, 2012]

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Uncertainty avoidance, or UA, is one of five cultural values and behaviors identified by the well-known organizational anthropologist Geert Hofstede, based primarily on data obtained through more than 116,000 questionnaires completed by IBM employees from 72 countries in 20 languages. Hofstede suggests "Ways of coping with uncertainty belong to the cultural heritage of societies, and they are transferred and reinforced through basic institutions such as the family, the school, and the state." Among 50 countries and three regions, Hoftstede's uncertainty avoidance index ranks Japan seventh, with an actual score of 92, and the United States ranks 43rd, with a score of 46. Citizens of countries with high UA rankings are characterized as relying heavily on rules and rituals, following well-defined and strictly upheld ways of doing things. People of cultures with low UA rankings, on the other hand, are flexible, content with unstructured and ad hoc approaches and procedures.

In subsequent studies by various researchers, the uncertainty avoidance rankings have been linked to tourist behavior, product development, accounting systems, and many similar customs and practices. Other researchers have replicated Hofstede's study in organizations other than IBM. On the other hand, 25 years after Hofstede collected his data, intercultural management researcher Denise Rotondo Fernandez and her colleagues set out to see whether the rankings still held true, and found that Japan had shifted substantially to weak uncertainty avoidance, while the United States had become a strong UA country. The researchers suggest that political, economic and social change may contribute to such attitudinal modification.

Difficulty Communicating in Japanese

Once described as the "greatest barrier to human communication ever devised," Japanese has a word order that is difficult for Westerners to master; information is often is exchanged in indirect ways rather than direct ways; and separate sets of words are used when speaking to friends, people of higher status and people of lower status. Former United States Ambassador to Japan Walter Mondale gave up learning Japanese but after only one lesson.

Many Japanese have problems with their own languages. Politicians often don’t understand the kanji (Chinese characters) in their own speeches and students have difficultly expressing what they really mean. A study in 2000, found that 81 percent of Japanese adults surveyed were confused by Katakana words. Studies have also shown that many Japanese do not know what common proverbs mean.

Some foreigners that speak Japanese well say that what makes Japanese so difficult to learn is not so much the language itself but the subtle way Japanese communicate. The Japanese people, for example, love to abbreviate or slightly alter phrases to express multiply meanings and "encapsulate a variety of nuances in a single word or phrase." Longtime resident of Japan John David Morely, once wrote, he "was accepted as a speaker of Japanese only as he became to his own ears, progressively inarticulate." He described a typical Japanese question as "suggestive, full of loopholes, offering escape hatches, and in fact unlike a question as it was possible to be" and said answering a question was "aiding and abetting the person who had asked the question" and "an accessory to the answer."

In his book “ Japanese Beyond Words “, Andre Horvat wrote, "The essence of Japanese-style communication consists of avoiding the equivalent of English pronouns as much as possible and configuring other parts of speech, such as verbs, nouns, adjectives and adverbs — even interjections’so that these other parts of speech transmit the clues as to who is talking to whom and about whom."

forming a line in the 19th century

Japanese Niceness

Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times wrote: "The Japanese people are, by and large, the nicest and most responsible people in the world. Not the friendliest, not the happiest, certainly not the funniest, but the nicest."

In Japan, taxi drivers sometimes give a discount for accidently taking passengers on a slightly out-of-the way route, the police give money to people who can't pay the subway fare, and passers by offer their own umbrellas to people who don't have one. Even the traffic lights say nice things.

Japanese often go out of their way to say nice things to the person they are talking to and people associated with the person they are talking to such as a children. Japanese consider it rude to screen calls on answer machines or even have answering machines. It has been said that “Japanese people are so cooperative and care for others that they can’t say “no.”

Japanese children are taught to be considerate, share their food, defer to others, and generally not be selfish. Kristof described an amusing experience he had teaching the game of musical chairs to a girl who was standing right in front of the chair when the music stopped but moved aside to let Kristof's son sit down. "I walked over and told her that she had just lost the game and would have to sit out," he wrote. "She gazed up at me, her luminous eyes full of shocked disbelief...'You mean I lose because I'm polite’ Chitosechan's eyes asked. “You mean the point of the game is to be rude?'"

Makoto Kurozumi, a professor at Tokyo University who specializes in the history of Japanese thought, believes that compassion has traditionally been one of the most important characteristics of the Japanese people. “The origin of this is a tradition of animism that teaches that everything, including plants and trees, has a spirit. That has cultivated a compassion for all living creatures, in the Japanese.”

Novelist Toshiko Marks told the Daily Yomiuri: “Back when many Japanese were still poor and could not survive without helping each other, the spirit of helping the weak was a fundamental part of conventional morals.”

The Japanese can also be naive, trusting and easily taken advantage of. A study found they tend trust those they have personal contact with while Americans are responsive to general trust and have believe a person’s reputation is valid to trust them.

Yoroshiku Onegai Shimasu — the All-Encompassing Japanese Expression of Niceness

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: The yoroshiku onegai shimasu expression is quickly mastered by learners of Japanese because it works so well in a wide range of situations, most frequently as something to say to open a conversation, discussion or speech, or to wrap things up and move on. Students of Japanese may find the literal meaning a bit strange, but few fail to be heartily grateful for this magic bullet that allows them to utter the mot juste on such a variety of different occasions. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, January 17, 2012]

The phrase is so vital that it can come to characterize an entire communicative event. Nigel Stott, an English education researcher, quotes an assistant language teacher (ALT) who wrote of "yoroshikuing," transforming the phrase into a dynamic gerund. "Please be nice to me" might sound lame and even needy in English but if it does the trick in Japanese and is easy to execute, no learner is likely to find anything problematic about it, and they quickly become merry yoroshiku-ers.

But for Japanese speakers, it's not so easy to come to terms with life without the word and its beseeching appurtenances. Sociolinguist Makiko Takekuro speaks of the "deletion-impossible and irreplaceable nature" of yoroshiku onegai shimasu. To support her assertion, Takekuro tried to replace naturally occurring instances of the phrase with other words in Japanese, noting that other ways of conveying the content nevertheless fail to accomplish yoroshiku onegai shimasu's essential function of demonstrating engagement in meaningful social interaction.

The politeness theory formulated by linguists Penelope Brown and Stephen Levinson posited the notion that the avoidance of imposition is one facet of politeness. This is accomplished in a number of ways, but one clear way this is achieved is through sidestepping direct requests in favor of wordings like "I wonder if you might be willing to...," "Is it possible to perhaps..." and so on. Yoroshiku onegai shimasu, a supreme example of deferent imposition, flies in the face of this way of looking at politeness, as many researchers on Japan politeness have pointed out, most notably Yoshiko Matsumoto.

So how does making a direct request end up being polite? Applied linguist Jun Ohashi posits the notion of "debt-credit equilibrium" as a central aspect of Japanese politeness. According to Ohashi, by making the yoroshiku invocation, a speaker makes plain that he or she is indebted to the other person, which is polite in a society that values reciprocity especially in terms of obligation, and it is expected that the debt will later be repaid.

In essence, a display of neediness, culturally impermissible in most English-language discourse situations, is at the heart of the expression. Ohashi further suggests that it is this profound orientation toward debt and the striving for its balance that leads to the frequent employment of the expression by both speakers in a conversation, even when one interlocutor is clearly the beneficiary. By also saying yoroshiku onegai shimasu, the benefactor graciously conceals his or her credit or disencumbers the recipient of their debt.

Difficulty in Finding an English Substitute for Yoroshiku Onegai Shimasu

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Many a Japanese person who speaks English quite well has asked me how to say yoroshiku onegai shimasu in English. People with advanced English skills must have realized long before that no similarly multifunctional equivalent exists in English, yet wistfully they cannot quite abandon the hunt. They maintain the hope to uncover the hidden formula which will make awkward junctures in English communication manageable in the same way. Non-Japanese who have lived in this country for a long time often likewise report a yearning for yoroshiku when speaking their native language. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, January 17, 2012]

Recently I was rereading an article by the applied linguists Leslie Beebe, Tomoko Takahashi, and Robin Uliss-Weltz, and I was struck by a phrase they used in connection with their own investigation into cross-cultural refusals, calling them a "sticking point." I had just that morning listened to one of my students give a presentation which began with an inept translation of yoroshiku onegai shimasu, perhaps one of the greatest sticking points for Japanese communicating in English.

Foreign-language textbooks obviously teach a variety of phrases that correspond to the kinds of things one might say in places in which yoroshiku onegai shimasu would be used, such as "Nice to meet you," "It is/was a pleasure to see you," and "I look forward to working/continuing to work with you." In opening speeches, it is possible to say something like "I appreciate the opportunity to speak to you today." Yet again and again students blithely ignore what they've learned and fall back on strange-sounding translations of yoroshiku onegai shimasu.

The problem is that the appropriate phrases in the target language can feel like poor stand-ins for the "real" thing. There is a sense that they simply don't fulfill deeper communicative objectives. While Japanese learners of foreign languages must resign themselves to making do with other less satisfying not-quite-counterparts to the Japanese expression, applied linguists have attempted to figure out what it is that yoroshiku onegai shimasu really does.

Praise, Modesty, Criticism, Apologies and Appreciation

Modesty is a highly regarded virtue. Athletes go to ridiculous lengths to be modest and avoid coming across as cocky. Japanese mothers generally don't scold their children and try to train their children as much as possible through encouragement and praise. This concept is practiced society-wide.

A study of compliment responses by Japanese researcher Junko Baba found that Japanese tend to downplay the compliment with questions, refusals, hedges, and self-mockery.

Japanese are highly sensitive to criticism. Insulting someone directly is considered extremely rude and vulgar because it causes serious loss of face, embarrassment and humiliation. Great lengths are taken not to criticize someone. Hints are offered in subtle ways. Criticism when it is done is done through third parties or when drunk. There are exceptions to this rule. Sushi instructors, for example, are notorious of wacking their apprentices when they make a mistake. The same is true with some sports coaches.

The Japanese are also famous for their fondness for apologizing as an act of courtesy. They apologize for all sorts situations. It often seems their reaction to any situation is to apologize first. Conversations often begin with a series of apologies.

Cross-cultural apology researcher Naomi Sugimoto examined 34 Japanese and U.S. books on etiquette written form the 1960s to 1990s and found Japanese conduct manuals devoted whole chapters to apologies while only one American book addressed the subject. The American book mainly addressed apologizing to strangers and while the Japanese books addressed apologizing to friends, neighbors and colleagues and examined apologizing on the behalf of others. Sugimoto also found that the word that popped up most often in American apologies was “sincere” while the one that popped up the most in Japanese apologies was “sunao” (“submissive, obedient”). The American manual also suggested offering an explanation along with the apology while the Japanese manuals infer that such explanations detracted from “the selfless surrender” that is expressed by an ideal apology.

Japanese Indirectness

The Japanese have developed "elaborate circumlocutions to create harmonious relations." They have a very indirect way of communicating and words like "careful dance" and "elliptical art" have been used to describe Japanese discussions. Directness in terms of speaking up for oneself and asking a lot of question is regarded as vulgar, rude and obnoxious.

In many cases Japanese are so in tune with the feelings and sentiments of other Japanese that they can communicate through innuendo, tautology, the subtlest of hints and by saying nothing at all in a way the seems almost "telepathic." The Japanese process of subtly feeling each other out to determine feelings and viewpoints is sometimes called "stomach talk." Foreigners have great difficulty picking up on these subtleties. Japanese say they sometimes talk to other Japanese, in some cases for hours, and have no idea what they are talking about.

“Omioyari” (“positive actions based on guessing”) is an important personal trait in Japan. In a study by applied linguist Catherine Travis 70 percent of Japanese surveyed ranked at it as important as being kind and cheerful.

Politeness often calls for ambiguity. Good news and compliments are also expressed indirectly. It is better to say to Japanese person "I wish I had you talent" rather than "you are talented."

Bad news is sometimes delivered in indirect ways that are crueler than the truth. Instead of being laid off, unwanted employees are given the hint to resign by being asked to write ten page reports on the same subject every two weeks, told there is no seat for them anymore in the office, no division wants them and finding work for them to do has become a nuisance. Doctors often refuse to tell terminally patients that they are seriously sick. A patient with inoperable pancreatic cancer, for example, is told that he or she has pancreatitis.

Discretion and Secrecy in Japan

Japanese don't like to criticize others or openly express their thoughts. They are reluctant to complain and speak out against litterers, pushy people and the like in public places even though they may be bothered b these behaviors. Speaking one's mind, volunteering opinions and being too inquisitive are often frowned up in Japan and keeping one's opinions to oneself and listening carefully to what other have to say are regarded as virtues and signs of maturity and consideration for others

Toshiyuki Masamura, a sociologist at Tohoku University, told the New York Times, "Westerners wonder why Japanese people don't clarify their thoughts. But for Japanese the overwhelming priority is the avoidance of confrontation."

The American humorist Fran Leibowitz wrote, "Everything in Japan is hidden. Real life has an unlisted number. But Japan is transparent if you realize that the Japanese are the French of Asia, if you realize that they're saying, 'Of course, I'm lying to you. That's what conversation is.'"

"Secrecy is an ingrained aspect of nearly every important institution in Japan," wrote James Sterngold in the New York Times. "Scholars, for instance are generally refused access to records on the origins of the imperial family. Doctors rarely tell patients... the nature of drugs being prescribed."

Not Troubling Others and Enduring in Japan

forming a line at the

subway station today The Japanese go to great lengths not to trouble other people. Book reviews are almost always positive, politicians don't lambast each other in public and subways commuters would often rather stand for a long time than seem the slightest bit pushy. In hospitals, mothers are taught to adjust their breast feeding habits of their infants to fit the schedule of the nurses and the other mothers.

“Gaman” ("enduring something difficult") is an esteemed virtue. The Japanese equivalent of the British stiff upper lip, it is a basic theme in almost every kabuki play and samurai movie and is expressed by the proverb “Good medicine tastes bitter” The late Emperor Hirohito once described it as "bearing the unbearable" and putting you best face forward.

A friend of mine worked on a fishing boat off of Alaska with a lot of Japanese workers that once a Japanese man lost his hand in a fish processing machine and was more concerned holding up production than he was about his injury. The great film director Akira Kurosawa once said, "The Japanese see self-assertion as immoral and self-sacrifice as only course to take in life."

Kimiko Manes, author “Culture Shock in Mind”, wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Japanese culture is not very open. When something goes wrong, a Japanese person frequently will not share the problem with others, instead suffering alone as they try to solve it. For example, suppose someone was not able to complete a task for a colleague by a certain date. Rather than explaining the nature of the trouble to the colleague, the Japanese person frequently tries to tackle it on his own....Asking the other party the reason for their difficulties would be construed as a sign of disrespect....The truth behind a problem frequently is not communicable, which can lead to bigger problems later. The Japanese reluctance to hurt or make the other party lose face overrides the temptation to rationally explain the issue at hand,.”

In regards to a couple having an argument, Manes wrote: “My Japanese sensibilities make me think that a couple who having problems, talking to each other would just make the pair even more emotional, and not solve any problems. Thus, I would think grumbling to others about their problems might actually help.”

Japanese often go through great lengths to be self-effacing. Social interaction are often full of self-deprecating remarks and efforts to play down any talents one may have.. Studies have shown that the “aw-shucks” Japanese demeanor may be more than politeness. In a study by cultural psychologist Steven Heine, Toshitalke Takata and Darrin Lehman performed with Japanese and Canadian university students, the students were led to believe they had performed better than average or worse than average before they took the tests. While the Canadian students performed more poorly on the test of they were led to believe they were below average the Japanese students performed more poorly on the test of they were led to believe they were above average, taking more time to make decision, being less confident about their answers, questioning the accuracy of the test. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri]

See Tsunami

Earthiness, Urine and Naked Men in Japan

Men unzip their pants and tuck in their shirts in public and take baths with their 11-year-old daughters. Boys and girls change from their street clothes into their sports clothes together in the same classroom in school when they are in the first, second and third grades.

Cleaning women going about their chores and little girls with their fathers are common sights among the naked men in men's dressing rooms in gyms, public swimming pools and public baths. A New York Times reporter recounted one episode in which an American wearing his underwear was told to remove it by a woman worker before he stepped into the bath. The reason for this was that the cleaning women had a job to do (keeping the dressing room clean) and she had to go about her duties even if it meant telling a man she didn't know to expose his private parts.

Bathrooms are sometimes unsegregated, and sometimes urinals in public bathrooms are situated where women passers-by can see men using them. Although less common than it once was, public urination for men is no big deal. Before the 1964 Olympic in Tokyo, men were encouraged to refrain from doing it because "foreigners are coming and they might think the Japanese are uncivilized." During the infamous urination riots of 1860s and 1870s soldiers battled with police and urinated in mass to protest public urination laws passed to satisfy demands of prudish foreigners in Japan.

Japanese are not as shy about talking about their feces and urine as Americans. They often excuse themselves from a social gathering by saying the equivalent of "I have to take a shit" or "I have to take a piss" when they have to go the bathroom. Children's television shows have film clips of hippos eating feces and songs about the pleasures of defecating.

Anger, Violence and Bullying in Japan

Japanese are taught to avoid confrontation and suppress their anger to preserve social harmony. One consequence of this is that they build up a lot of stress inside them. Heavy drinking is one way it is let out.

The expression “okuru toki wa okoru” (“When he gets angry he gets angry”) means that even if a person normally doesn’t get angry they will get angry if there is a good enough reason.

Richard Lloyd Perry wrote in the Times of London, “In almost 15 years here I have only seen three fist-fights in Japan. Each one exploded out of nowhere, with no preliminary shouting or goading or facing off?and came to an end with equal abruptness.”

The Japanese are becoming increasingly stressed and aggressive. Some blame economic hard times and increased competition for the condition best reflected in the emergence of monster parents going after teachers (See Education) and doctors and health care workers at hospitals. A doctor who said much of his day is taken up by demanding parents screaming at nurses demanding that hospital hours be changed to fit their schedules told the Time of London, “People sense their rights is getting stronger and stronger but the expression of that is just becoming violent and radical.”

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported in December 2001: “A 48-year-old man of Shinagawa Ward, Tokyo, was arrested on Saturday on suspicion of fatally striking an elderly man in a fit of rage after the elderly man advised him not to use a crosswalk against a red light, police said.The Metropolitan Police Department said Kikuo Yamane, who identified himself as a company executive, was on his way to go shopping with his teenage son at the time. He admitted the allegation, saying, "I was so angry at what I was told by [the elderly man] that I punched him." According to the police, the incident occurred in front of JR Oimachi Station in the ward at about 7:35 p.m. on November 12. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 26, 2011]

Relations and interactions are often defined by who has power and who doesn’t. There is a tendency to attack the weak. See Bullying, Education. See Hazing, Sports

Image Sources: Visualizing Culture, MIT Education and Ray Kinnane

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013