JAPANESE SOCIAL LIFE

“Ningen kankaei” is a Japanese term that describes the concepts of indebtedness and obligation which are central to understanding social relationships in Japan. It is manifested in the careful tally that individuals keep of the favors they have done for people and the favors that have been done for them and the endless effort to “repay” people back either with an equivalent favor or gift that shows appreciation. Ruth Benedict said that a primarily goal of every Japanese is not to owe anyone anything.

Studies by anthropologists suggest that the Japanese sense of self is more “relational” than individualistic. The psychologist Takeo Doi has argued that Japanese interpersonal relationships revolve around the concept of “amae” (“dependency,” “depend on or presume another’s benevolence” or “mutual indulgences to each other’s weaknesses”) built around trust and mutual dependancy. These relations are often developed with the help of alcohol after work because daily life in Japan is restricted by social rules and demands to exert self-control and behave responsibly and appropriately.

With the exception of a few jingoist periods, Japan has a history of tolerance. Some attribute this to the eclectic nature of the first Japanese who arrived from the Asia mainland, the islands of Southeast Asia and the islands off of Siberia.

Senior (“sempai”)-junior (“kohai”) relations are very important. They manifest themselves between students of different grades in school; bosses and employees at work; and in other hierarchies or organizations, teams and clubs. See Children.

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: JAPANESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE POLITENESS AND INDIRECTNESS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SOCIAL LIFE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SOCIETY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE REGIONAL DIFFERENCES Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Journal of Personality by the Japanese Society of Personality jstage.jst.go.jp ; Japanese Society and Culture in Perspective habri.co.uk ; Japanese Culture, a Primer for Newcomers thejapanfaq.com ;Traditional Japan, Key Aspects of Japan japanlink.co ; ACE Japan , Japan Association for Cultural Exchange acejapan.or.jp ; Opinion on Asian Fetish colorq.org ; What Japan Thinks, a blog with info on demographics and statistics whatjapanthinks.com

Academic Articles Gender-Role Personality Traits in Japanese Culture pdf file mwsu.edu/sociology ; Advise Giving and Personality Traits of Japanese University Students jalt.org/pansig ; Confucianism, Personality Traits and Leadership in Japan pdf file psychology.csusb.edu ; Blood Types and Personality Japan Visitor on Blood Types japanvisitor.com ; Blood Types and Personality issendai.com ; Academic Paper on Blood Types and Personality sciencedirect.com

Books Classic books on the Japanese character and society include “The Chrysanthemum and Sword” by Ruth Benedict, “Vertical Society” by Chie Nakane, and “Bushido” by Inazo Nitobe. Among the more recent books on these subjects are “Japan’s Cultural Code Word: 233 Key Terms That Explain the Attitudes and Behavior of the Japanese” by Boye Lafayette De Mente (Tuttle, 2004) and “Japanese Patterns of Behavior” by Takie Sugiyama Lebra. Sites for Expats Japanable site for Expats japanable.com ; That’s Japan thats-japan.com ; Orient Expat Japan orientexpat.com/japan-expat ; Kimi Information Center kimiwillbe.com ; Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report on Japan fco.gov.uk/en/travel-and-living-abroad ; Student Guide to Japan www2.jasso.go.jp/study ; Japan in Your Palm japaninyourpalm.com

Friendships in Japan

The Japanese tend to hang out with people they work with or have known for a long time. They don't make new friends easily and are more comfortable with formality and rituals than spontaneity. Social events, like weddings, in which people who don't know each other are thrown together, tend to be very structured and scripted so people don't feel pressure to make awkward conversation with strangers. Many students say they join clubs at school because they have difficulty making friends otherwise.

Japanese like to do things in groups as anyone who has seen a Japanese tour group in action knows. They feel comfortable doing things with their friends and get a certain sense of security and reassurance from being with people like themselves. They tend to be absorbed in the group and their activities and could care less about what people outside their group think of them.

In a survey by researchers Eriko Maeda and L. David Ritchie Japanese students were asked what they wanted from a friend. The students said things “on the same wavelength," “concerned for me," plus things like “does not ask too much about my private life” and “aiming toward the same goal in a club.” The Japanese students said they like friends that they feel comfortable with and someone who can “cheer me up” and acts in a “controlled manner.”

The Japanese are very used to having people around all the time. Some Japanese get very lonely when they are alone and endure almost unbearable stress if the people around them are angry at them for one reason or another.

Social Activities in Japan

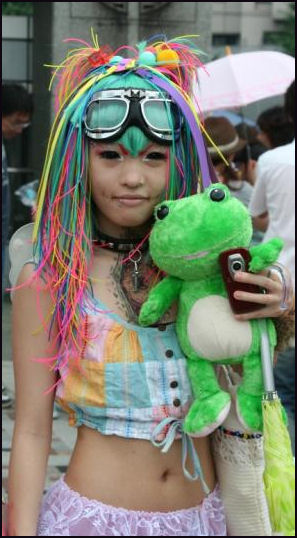

cosplay buddies The Japanese don't invite people to their house very often partly because they feel a lot of stress about making sure their guests are happy and well fed and partly because homes are small and regarded as private places just for family members. Japanese generally don't stop by someone’s house unannounced and just hang out.

Japan has more restaurants and drinking places per capita in part because people have so little room in their homes and go out when they entertain and socialize.

Japanese are not great minglers. They tend to hang out with people they know. Conversations at parties often involve detailed analysis of a certain topic.

It is much more common for couple to go their separate ways at social events, including important ones like weddings.

Listening, Talking and Stories in Japan

Studies of Americans and Japanese have found that Japanese tend to listen to someone speaking to them for a period of time without interrupting while Americans often interrupted and finished the sentences of people speaking to them. A study of 20-minute conversation segments found that when Americans were talking there were 79 speaker changes, 27 overlaps and 52 interventions and when Japanese were talking there were 44 speaker changes, 14 overlaps and 30 interventions. At the same time the number of “back-channel responses” — that indicate a speaker is listening — were five times as frequent among Japanese than among Americans.

Describing top executives at a business meeting, Japanese culture expert Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Often they sit quietly, noncommital , as various team members wrestle and wrangle with ideas. At times it seems they might even be dozing. And yet, as the end of the meeting draws near, they will speak up, summarizing the points made and fitting everything into a neat package that might be titled “the direction it appears best to take based on what everyone has said.”

Americans tend to be more comfortable than Japanese speaking directly and expressing the real story on disagreeable subjects. That doesn’t mean Japanese can’t or don’t just that are more uncomfortable doing it. In a community situation Japanese neighbors are more likely to express their displeasure about something like a noisy dog with an anonymous letter in a mailbox than a face-to-face meeting which Americans tend to regard as the most honorable way to address such a problem.

Sometimes it seems like Westerners enjoy telling stories more than Japanese do. Conversations involving Westerners and lectures by Western teachers seem to be peppered with stories much more than conversations and lectures by their Japanese counterparts. A study by applied linguist Yasanari Fujii of Japanese and Australian speakers found that Japanese were hesitant to launch into a story and needed repeated probes “to ensure that listeners are not hostile” while for Australians “anything short of rejection of the story will lead to the story being told.”

Many Japanese find the American tendency to say things are so great and wonderful to be a little over the top and even off-putting. But studies have found that of anything Japanese are more likely to get carried away with their use superlatives such as “ sugoi” (“great”) than Americans.

Offers and Invitations in Japan

Japanese tend to treat invitations more seriously than Westerners. Extending an invitation is not something that is done lightly. And accepting an invitation is treated as an obligation and something one can not back out of easily.

Japanese often interpret offers and invitations differently than Americans and other Westerners. If a busy Japanese host tells guests who arrive early at a party to help themselves to some drinks, Japanese are likely to decline, believing that the offer was a way of telling the guests that the host was busy and they should not trouble the host. In the same situation American guests would be more likely to see the offer as genuine and help themselves to drinks. {Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri]

Children routinely talk about plans to do something even if someone present has not been invited. This behavior is generally seen as rude in the United States. In Japan, the onus is on the excluded child to stay quiet and not whine rather than on other children to not talk about their plans.

Japanese often regard an American invitation as something akin to a sales pitch that is difficult to refuse. In America, expressing the idea “we need you” in an invitation is often viewed by the person who receives the invitation as a compliment that their presence is important. Japanese, on the other hand, often feel stress, when confronted with an invitation with such wording, viewing it as an obligation they must honor. Consequently Japanese often handle invitation and the response with lighter, more indirect suggestions so it easier for the person being inviting to delicately refuse.

Singing and Photos in Japan

singing Shinto shrine girls Japanese generally are shyer about dancing than singing, whereas the reverse is often true with Westerners. Japanese children generally have few opportunities to dance when they grow up and feel awkward doing it, but they do a lot of singing in school and tend to regard it as a fun activity like recess or sports. In karaokes, singers with good voices of course are admired more than those with bad voices but even bad singers are applauded for their effort.

The Japanese are also fond of having photographs taken of themselves with their friends. Teenagers form long lines behind photo machines and adults on hiking trips seem to do more photo-taking than hiking. This is because the Japanese treasure their friends and the memory of good times, and the value of an activity is often measured more in the bonding that takes place than with the activity itself, plus they get enjoyment from posing and looking at the photos later on. Photos without people in them are often considered boring.

Japanese Communications Between Friends

Sometimes Japanese are described as being more quiet and even silent than other people but day-to-day life seems to show they enjoy talking and can be as garrulous as any other people. Studies have shown though that Japanese describe more situations as being “noisy” and there does seem to be a cultural acceptance of “companionable silences” in which it quite to alright to hang with someone and not say anything.” [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri]

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Important life events aside, the amount of information that may be shared by both American men and women in the process of making friends can be surprising to those accustomed to the Japanese minimalist approach. Virtually any event that might have had an impact in making the person they are today is potential fodder for the life report. Those who refrain from any soul-baring may be viewed as not fully engaging in the friendship.” [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, November 2, 2010]

“Behavioral scientists Joanna Schug, Masaki Yuki and William Maddux suggest that "relational mobility" is a key factor in determining the role of self-disclosure in strengthening personal relationships. The researchers administered questionnaires to Japanese and American university students that asked things like how likely it was that they would reveal certain types of personal information to their best friend or closest family member, and to evaluate statements like "People like me when I trust them enough to tell them about my personal problems." At the same time, they investigated relational mobility by asking the students to assess the opportunities for people in their immediate society to get to know other people and choose who to interact with. In this way, relational mobility means the degree to which people are able to move on when a friendship does not feel satisfying.”

“Schug and her colleagues found that self-disclosure was higher among the American students than among the Japanese students but also that within each culture it was closely linked to relational mobility. That is, even among the Japanese students there was a higher level of self-disclosure in social contexts in which people had many chances to meet new people and form new friendships. Sharing private information appears to serve as an important way in either culture to strengthen bonds when friends may easily take up with a new buddy. According to Schug and her colleagues' research, American students generally have more relational mobility and this motivates them to engage in more self-disclosure to bolster friendships that are important to them. When Japanese students are in similar circumstances of relational mobility, they do the same thing. The researchers further posit the idea that in situations with less relational mobility, when there is not a need to tell others about private details in order to strengthen a friendship, people may actually refrain from soul-baring in order not to risk damaging the existing relationship.”

In a study conducted by Kate Elwood of Waseda University, in which American and Japanese to offer a responded to a friend who has been turned down a second time for an internship, 87 percent of the Americans expressed sympathy while only 10 percent of the Japanese did and 93 percent of the Japanese made encouraging remarks while only 33 percent of the Americans did.

Friendship and Facebook-Style Social Networking in Japan

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Social network researchers B.J. Fogg and Daisuke Iizawa made a study of the process of socializing on Facebook and Mixi, Japan's leading social networking service. The researchers note that when new users begin to use either SNS (social networking service) they are prompted to create personal profiles. Right off the bat, Facebook encourages users to reveal a lot of personal information, such as religious views, sexual orientation and romantic relationship status.”[Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, March 29, 2010]

“Mixi, on the other hand, doesn't ask for anything so private, but rather simply for hobbies and personal interests, and even this kind of information is not solicited immediately. Rather, Mixi users begin by making a self-introduction. A model is actually provided by Mixi, which the researchers translate as: "Hello, my name is Mixi Tanaka. I am a college student. I would like to be a counselor to help people. I am wondering if I can communicate with your friends in Mixi. I'm looking forward to meeting you on Mixi." Later, after trust has been established with this sort of innocuous profile, users add their hobbies and interests.”

“Fogg and Iizawa further conducted an online survey of Facebook and Mixi users regarding their friends on the social networks. While the average number of SNS friends was 281 among Facebook users, it was 58 for Mixi users. Twenty-three percent of the users of the American SNS hoped to increase their friends, but only 9 percent of the Japanese SNS did. Moreover, the "ideal" average number of SNS friends for Facebook users was 317 compared to 49 for Mixi users.”

Privacy, Trust and Facebook in Japan

Japanese society has recently been increasingly keen on protecting individual privacy, according to an article in the Yomiuri Shimbun. After the full enforcement of the Personal Information Protection Law in 2005, phone numbers were removed from students' name lists at schools. Local welfare commissioners, who visit homes of the elderly and other people who need assistance, had trouble obtaining information. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 11, 2011]

"It's time to rethink excessive protection of personal information," said Kansai University Prof. Yuki Yasuda, who specializes in social network analysis. "By disclosing personal information, it will be easier for people to obtain the trust of others, which enables them to moderately connect with each other. After the March 11 disaster, it has become a trend for people to attach more emphasis on such bonds," she added. Yasuda believes social networking services such as Facebook that require users to register with their real name are a sign that people want to connect with each other from a distance that is not too far and not too close.

According to the Tokyo-based research company NetRatings Japan Inc., the number of visits from personal computers to Facebook in Japan reached about 11.3 million in October, about four times larger than the same period last year. Yasuda herself has a Facebook account. "Social network services disclose relationships of users to others. Making human relationships visible to others leads to mutual trust," Yasuda said. "For these reasons, young people think it's better to disclose personal information than to hide it," Yasuda said.

Making Friends in Japan

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “In a provocatively titled article "Friendliness does not make friends in Japan," communications researcher Blaine Goss recounts an episode in which he and a Japanese colleague were making a script related to asking directions when lost in a city. Goss wrote "You should look for a friendly person and ask for directions," but his cowriter suggested "kind" seemed more fitting for Japanese users of the script. Goss posits that a more reserved kindness is a necessary precursor to gregarious friendliness in Japan, pointing out that those who attempt too much too soon are likely to be negatively assessed as narenareshii, or overly familiar. Obviously, among Americans as well, there are those who are sometimes a bit too eager which is off-putting, but the degree or point at which friendly becomes excessively friendly clearly differs between the two cultures. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, March 29, 2010]

‘”Several years ago, when I was a university student in Japan, I became good friends with a Japanese classmate I'll call Ikuko, who had lived in the United States for some years. When Ikuko got married, I was asked to give a speech at the reception and I asked for advice from some other Japanese friends as I prepared it. All of them suggested I mention the process of becoming friends with Ikuko in my speech. Umm...the process” We sat next to each other in class...and became friends. There wasn't a lot of "process" to it. At that time, I noticed that one word kept popping up in my friends' recommendations: uchitokeau. Uchitokeau suggested to me melting into each other, which seemed a rather amorous way to describe a non-romantic friendship. But as I learned, it is often used to describe the process of gradually becoming true friends.”

“The class that Ikuko and I took together was Chinese History. It was a standard lecture course with no discussions, but we somehow naturally struck up conversation before class one day, and as the weeks went by we became close friends. I'm glad that we became friends, and more than 20 years later, Ikuko is still a friend, but the process seemed pretty normal. On the other hand, now that I am a teacher myself, I am interested to note how often the third- and fourth-year students tell me that one of the reasons they enjoy my class is the group work gives them an opportunity to make friends — from what they tell me, apparently making friends with classmates is a new experience for them.”

Once a friendship is formed the bond is often very strong. The Japanese expression “We eat from the same bowl” describes how friends shared pain and laughter with one another.

Winning Friends and Influencing People in Japan

Dale Carnegie's famous self-help book “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” first was published in 1936, has been a best seller in Japan. Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Much of Carnegie's advice fits right in with common Japanese behavioral norms and communicative patterns. For example, Carnegie advises, "Don't criticize, condemn or complain," "Call attention to people's mistakes indirectly," and "The only way to get the best of an argument is to avoid it."...Interestingly, the "influence people" part of the title takes center stage in the Japanese title, Hito o Ugokasu, or "how to move people," omitting the "winning friends" bit. But what it means to influence people may be different depending on culture. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, June 25, 2012]

Cultural psychologists Beth Morling, Shinobu Kitayama and Yuri Miyamoto asked Japanese and American university students to describe one of two different types of situations. The first group was asked to write about situations in which they had influenced or changed people, events or objects according to their own wishes. The other group was told to provide information about situations in which they had adjusted themselves to people, events or objects. The researchers found some interesting differences. Ninety percent of the American situations related to influence involved another person, but only 61 percent of those described by the Japanese respondents did. The Japanese situations were often concerned with things like shifting furniture or work schedules. Additionally, in 21 percent of the situations of influence described by the Americans, a positive consequence for other people was indicated. For example, one respondent mentioned helping his brother study, which led to his getting an A. In contrast, only 5 percent of the Japanese situations of this type alluded to a beneficial outcome for someone else. In fact, 33 percent of the Japanese situations of influence referred to going against situational demands. For example, "My mother was used to serving bread, but I asked for rice.”

There was divergence between the groups related to the adjustment situations, as well. The Americans were much more likely to phrase their adjustment as an obligation, using phrases like "I had to adjust..." Forty-one percent of the adjustment situations described by the Americans used this kind of wording compared to only 9 percent of the Japanese situations. At the same time, the Japanese respondents were more likely to make explicit references to the gap between what they would have done and what they ended up doing as a result of modifying themselves to match surrounding people, events or objects. Twenty-three percent of the Japanese students wrote things like, "I was not having fun, but I pretended to enjoy myself," but only 8 percent of the Americans similarly made the contrast plain.

Morling and her colleagues suggest that for the Japanese, surmounting their personal inclination was a positive sign of dedication to the relationship, while for the Americans following the dictates of situational demands was a requirement, not a voluntary action. The researchers then showed new groups of Japanese and American students descriptions of situations that had been produced by the earlier respondents and asked them two questions concerning each situation. One was whether, in the situation described, they would feel that they had done something because of their competence, power, or effort--what the researchers term "efficacy." The other was whether, in the situation described, they would feel merged with other people, or "relatedness.”

As expected, both groups felt more efficacy in the influence situations and more relatedness in the adjustment situations. Perhaps also predictably, the Americans felt more efficacy in the influence situations than the Japanese did, and the Japanese felt more relatedness in the adjustment situations than their American counterparts did. What surprised Morling and her colleagues more was that the influence situations described by Americans received high relatedness ratings in addition to high efficacy ratings on the part of both the American and Japanese respondents. The researchers conclude that American influence situations are "distinctly social events," which engender feelings of closeness on the part of the influencing person.

Compliments in Japanese

In the article “Intercultural encounters: The management of compliments by Japanese and Americans” — published in in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology in 1985 — by D.C. Barnlund and S. Araki: An interview with 56 participants (20 Americans in the US, 18 Japanese in the US, and 18 Japanese in Japan) revealed that the Americans gave compliments much more frequently than the Japanese — Americans reported to have given a compliment in the previous 1.6 days whereas Japanese had only done so in the previous 13 days. Some of the findings: most frequently praised features were appearance and personal traits among Americans and acts, work/study, and appearance among Japanese. American used a wider range of adjectives than Japanese who used fewer adjectives and adjectives with less of a range in meaning. In responding to compliments, Americans tended to accept compliments or justify or extend them; Japanese questioned their accuracy, denied them, explained the reason why they were not deserved, or responded by smiling or saying nothing at all. The closer the relationship was, the more frequently Americans gave compliments, while Japanese were less likely to offer praise. Female speakers in both cultures were more likely to give and receive compliments. The authors also report their findings from a questionnaire given to 260 Japanese and 260 American participants. Although preferred strategies of expressing admiration were similarly indirect among both the American and Japanese participants, Japanese preferred noting one’s own limitations twice as much as Americans and relied on non-verbal communication much more frequently. Americans preferred giving praise to a third party twice as much as Japanese. Some other findings are in relation to gender, topic focus, and communicative partners. [Source: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition (CARLA), the University of Minnesota]

In the paper “A study of compliments from a cross-cultural perspective: Japanese vs. American English” — published in Working Papers in Educational Linguistics in 1986 — by M. Daikuhara: 115 compliment exchanges were collected in natural conversations by 50 native speakers of Japanese and analyzed in terms of age, gender, relationships, situations, and non-verbal cues. The most frequently used adjectives in the compliments were: ii “nice/good,” sugoi “great,” kirei “beautiful/clean,” kawaii “pretty/ cute,” oishii “good/delicious,” and erai “great/deligent.” The “I like/love NP” pattern never appeared in the data. Although there was a great similarity between compliments in Japanese and English (as was found by Wolfson, 1981) with regard to the praised attributes, in Japanese, compliments about one’s ability or performance (73 percent) or character (rather than one’s appearance) were common. While Americans praised their family members in public, the Japanese seldom complimented their spouses, parents, or children as this would be viewed as self-praise. Ninety-five percent of all responses to compliments fell into the “self-praise avoidance” category, which included rejection of the compliment (35 percent), smile or no response (27 percent), and questioning (13 percent). The author argues that compliments in Japanese seem to show the speaker’s deference to the addressee and this perhaps creates distance between the interlocutors. The addressee fills in this gap by rejecting or deflecting the compliment in order to sustain harmony between the interlocutors.

Japanese Sense of Humor and Jokes

21st century cosplay girl The Japanese enjoy a good laugh. Bars are filled with drunk men laughing uproariously; late-night television is dominated by silliness and mean jokes; and it said that while Japanese laugh less at work than Westerners they laugh more outside of work.

Even so Japanese are not known for having much of a sense of humor. They are better known for their dour expressions and businesslike manner. Some of their most famous jokes are about death. A well-known “rakugo” ("comic tale") begins with a couple making a pact commit suicide. The man says "Let's use razors." The woman says, "Let's not, the wounds take too long to heal."

A typical rakugo joke goes like this: a group of boys are sitting around talking about things that scare them. The usual things, snakes, spiders are mentioned. One boy says he’s afraid of “manju” (sweet bean paste buns) then says he needs to take a nap. While he’s sleeping the other boys figure they will play a joke on him and place some manju next to his head. When he wakes up the boy first acts afraid and then laughs and eats the bun, saying he actually loves the buns. When the boys ask what he is really afraid the boy says, “Right about now I’m afraid of a nice cup of tea.” [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri]

Sometimes the Japanese sense of humor can be quite strange and even cruel and creepy. Anime, films television shows and manga often feature violent humor and violent sex. “Batsu” (“Punishment”) games shows with contestants who are “dunked, slammed and swirled,” slapped around by the host or who are forced to do potentially dangerous tasks are fairly common in Japan. Fuji television comedy show “ Tunnels ni Minsasan no Okagedeshita” features “human Tris” segment in which kids have to make shapes or they are dumped into a pool of water.

I've seen shows in which guests were given an electric shock for failing to negotiate a maze, forced to go as long as possible without going to the bathroom and choked on a ball rolled down a ramp into their throat. These shows often also feature women placed into various compromising and humiliating situations, such as stripping if they lose a game of ping pong. In “Hexagon II” celebrity contestants are given painful electric shocks if they give the wrong answer to trivia questions.

Partly explaining why shows of this kind are so popular, Ian Buruma, wrote in “Behind the Mask”, "violent entertainment and grotesque erotica are still important outlets in what continues to be an oppressive social system." Some sociologists have suggested the shows may be a manifestation of a morbid Japanese fascination with destroying beauty.

Henshu Techo wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Here is a joke about a fight between a Japanese man and a Chinese man. When a police officer came to question them, the Chinese man said, "The Japanese guy started the fight when he hit me back." This story is included in "zoku Sekai no Nipponjin Joku-shu" (a sequel collection of world jokes about Japanese people) written by Takashi Hayasaka, part of the La Clef paperback series published by Chuokoron-Shinsha. [Source: Henshu Techo, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 22, 2011]

It is not necessary for one of the characters in the joke to be Japanese. The joke would work regardless of the nationality of the person fighting the Chinese man.

Gestures and Expressions

On the reaction of different cultures to different expressions and gestures Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Semantic interpreter Heeryon Cho and five other researchers used an online pictogram survey to assess divergent construal of meaning between American and Japanese respondents. Five hundred and forty-three Japanese people and 935 Americans responded to the survey, which included 120 pictograms, 19 of which were identified as having culturally different interpretations. Some of the differences were not surprising for those familiar with gestures in Japan and America. For instance, an image of a person raising their hands above their head to form a circle was understood to mean OK or correct by Japanese respondents, while Americans suggested it was exercise. The figure of a person with hands pressed together signified praying for many Americans, but meant please or thank you for Japanese respondents.”

“More unexpected were differing frequencies of interpretations related to gender and color. For the Japanese, it was more cut-and-dried. A simple figure drawn in red was seen as a woman or girl by 92 percent of the Japanese respondents, but 32 percent of the Americans thought it was a man or boy. Similarly, the same figure drawn in blue was more likely to be seen as a man or boy by the Japanese respondents than the Americans. Smiley-face pictograms were frequently perceived differently. Twenty-five percent of the American respondents interpreted a pictogram of a simple face with lips pursed and two horizontal lines indicating that the face was turning to the right as whistling. On the other hand, 30 percent of the Japanese who took the survey felt that the same pictogram expressed feigning ignorance, an interpretation not provided by the Americans. Only 5 percent of Japanese respondents thought the face was whistling.”

Similarly, a face with simple furrowed eyebrows, a wavy line for a mouth and wavy diagonal blue lines on either side was viewed as a representation of being cold by 50 percent of the Japanese but only by 11 percent of the Americans. Thirty-nine percent of the Americans saw it as "scared," "worried," or "nervous," but only 17 percent of the Japanese wrote that it was "scary" or "trembling."

“Some years ago,” Elwood wrote, “I read an essay by an American woman married to a rather reticent Japanese man. In it she confessed that things really got going romantically for them after he wrote an X on the back of an envelope enclosing a letter he had sent her. An X has signified a kiss for English writers since the 18th century, and this mark was the confirmation she needed regarding his feelings for her. It was only after they were married that she found out that Japanese people routinely mark envelopes with the kanji shimeru which means "closed" and resembles an X. His letter was closed, but not sealed with a kiss as she had imagined. Wrongly interpreted, the mark nonetheless achieved an amorous objective. We strive for cross-cultural understanding, but sometimes cross-cultural confusion also works wonders.”

Smiling, Laughing and Lacking a Sense of Humor

Japanese are not known for being big smilers. There are schools like the Smile Amenity Institute that teach people how too smile. Some businesses pay their employees to attend such school. Some schools teach their students to smile by relaxing their nose, loosening their tongue, placing their hands on their stomach and letting the "poisons" escape from their bodies. Other teach them to smile by biting down on a chopstick and laughing with their heads underwater.

Many Japanese laugh, smile or giggle when they are embarrassed or make a mistake rather apologizing or making an excuse. They don't mean to be rude. A smile is regarded as way to escape an uncomfortable situation. A laugh is regarded as a kind a apology. If you laugh along with them it means that you accept the apology. Japanese also sometimes smile when discussing sad topics because it is considered inappropriate to express private sadness.

Another reason that Japanese are reluctant to laugh openly is that they have a great fear of being laughed at and they don’t want to appear rude and laugh at somebody else. Alfons Deeken, a sociologist at Tokyo University, told the Washington Post, "Especially older people were taught to laugh was not to be serious. It is too frivolous. And to be frivolous is to lose face. Everyone is told as a child you are not to lose face."

Donald Richie begins an essay in his 1987 book “ Different People: Pictures of Some Japanese “ with his recollection of seeing a woman narrowly miss catching a train, and reacting with a smile and then makes note of the prevalence of "disappointed grinners" in Japan. Richie suggests that smiling in the face of thwarted wishes expresses a basic attitude in which personal preference is set aside for an "appreciation of reality" that is quite different from the American outlook regarding similar setbacks. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, March 1, 2010]

Some say the Japanese lack a sense of humor and say this dates back the samurai era. Samurai, like American cowboys, were admired as strong, silent types who didn't express their feeling or laugh or smile. One sociologist told the Washington Post, "It was said that it was enough for a samurai to smile once in three years. And then only with one cheek."

Other say the lack of humor dates back the Meiji period when hard work and Prussian propriety were held high as social virtues and jokes and jocularity were dismissed as a frivolous waste of time. Things only get worse under Japan's military leaders.

Another reason that Japanese seem so dour is that they tend to be formal with strangers and open more with their friends. Kieme Oshima of Tokyo University told the Washington Post, "Americans tell jokes to break the ice with strangers or just for the fun of laughing. Japanese don’t do that. We are polite and serious on the first meeting. We tell a joke only after we have a good relation with someone. A joke is told between friends to assure that we can laugh at the same things and have solidarity."

Irony and Sarcasm in Japan

The Japanese sense of irony, usually translated to “hiniku”, is different from the Western sense of irony. Efforts by Westerners to be ironic and sarcastic are often taken literally or are greeted with blank stares or puzzlement. When an American trying to be funny or clever expresses irony through a reverse opinion of what is really the case Japanese often do not pick up on it.

Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “In Japan, another ironic nonstarter is the of reversal in imperatives to lightly — or nor so lightly — to suggest that another person’s action or behavior is inappropriate or indirectly request the opposite behavior . For example, someone who is crowding on too close to another might say,”Why don’t you draw a little nearer? Similarly, a wry “Thanks a lot” when jostled into spilling a cups doesn’t make sense on Japanese.”

For Japanese hiniku is usually equated with sarcastic criticism. If someone says the a house is tidy when it really isn’t the listen either doesn’t get it, takes the comment literally or interprets the comment as mean sarcasm not friendly teasing or a gentle indirect hint as many American would take it.

Be careful when using irony or sarcasm because the Japanese can be very sensitive and easily take offense. Sarcasm often is not well received in Japan.

Interpretations of Teasing in Japan

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Playful mockery may differ across cultures in function, form, and content. Educational researchers Eiko Ujitani and Simone Volet conducted a study of Australian and Japanese university students who all lived in the same international dormitory at a Japanese university. The students were asked to discuss "critical incidents" of an intercultural nature. Among the Japanese participants, more than a third of the reported incidents were related to joking and teasing. In one incident, remarked on in the interviews by many students of both nationalities, an Australian male student said to a Japanese female student who had taken a small portion of food at a party, "You are eating like a pig!" The student blushed and stopped eating. The interviews revealed that all of the Australians recognized that the man had been teasing, but none of the Japanese students had a clue what the intention of the student might have been in saying something so obviously inaccurate, even when reflecting upon the incident later. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, August 31, 2010]

“Ujitani and Volet's study makes clear the difficulty in recognizing teasing conventions of another culture. A study by intercultural gerontology researchers Berit Ingersoll-Day, Ruth Campbell, and Jill Mattson similarly points to differences in the types of teasing between older Japanese couples and American couples. Japanese and American couples were asked to jointly tell a story about their marriage. The ensuing narrative interactions were then assigned communication codes such as prompting, questioning, echoing, contradicting, and teasing. The researchers found that couples of both nationalities engaged in teasing quite often, but the manner of teasing was different. According to their findings, the Japanese couples' teasing was frequently competitive, with, for example, acerbic comments about who was responsible for a child's positive traits. On the other hand, the American couples appeared to use teasing to "detoxify" difficult issues such as illness. The researchers further note that the Japanese couples were especially animated in their interaction during the teasing sequences of their narratives.”

“Applied linguist Naomi Geyer observes that teasing in groups in Japan often occurs when a social norm has been violated. Geyer made a discourse analysis of two teachers' meetings at different high schools in which one of the teachers at each meeting was teased. In each case, the light ridicule took the form of assigning the taunted teacher an unrealistic task. In the first instance, the head teacher announced the need for teachers to hold supplementary lessons during the summer for about three days. The other teachers made minimal responses of consent, but a young male teacher explicitly agreed with the announcement. The overt support was judged improper because it seemed as if he had the authority of contributing the last word on the matter, though no one stated this directly. Instead, the head teacher suggested the young teacher should hold supplementary lessons every day during the summer, a joking proposal that was taken up enthusiastically by the others at the meeting.”

“At the other meeting, a summer cookout was being planned. Another young male teacher asked who would make the teachers' meal. His question also was deemed inappropriate, and consequently he was first answered by the main teacher as if he were a child. This was followed by another teacher's suggestion that the teasing target would be the main cook. As in the other teasing segment, discussion of this facetious arrangement was swiftly continued by other meeting participants as a fait accompli.”

“While in Geyer's data the teasing is triggered by unwitting violations of conventions among teachers, communications researchers Lisa Mizushima and Paul Stapleton observe that teasing in Japan is often a ritualized interaction that may be deliberately initiated by the person who is subsequently teased. In one example, a man who has offered to give a friend's sister a lift suddenly asks in a comically low voice whether the sister has a boyfriend, an invitation for the others present to humorously criticize his bogus ulterior motive. In another instance, a speaker brazenly flouts convention by agreeing with praise, similarly triggering mocking disparagement. In this kind of playful condemnation, all of the participants, including the norm violator, are aware of the correct thing to do, which is reconfirmed through a humorous infringement.”

“At the dinner with Satomi and her father, at one point Mr. Sasaki, in discussing takeout meals, referred vaguely to French fries as jagaimo no kara-age ("potatoes deep-fried like chicken"). His rather fuddy-duddy way of talking about such a ubiquitous fast food provoked perhaps the greatest laughter of the evening — and further teasing from Satomi about her father's lack of knowledge of contemporary culture. Afterward, I couldn't help wondering if Mr. Sasaki had deliberately played up his outmoded persona with the express intention of heightening the guffaws and eliciting more playful ridicule. Calculated or inadvertent, it was all in good fun.”

Image Sources: 1) Hector Garcia 2) xorsystblog 3) xorsystblog

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013