BIRTH CONTROL IN JAPAN

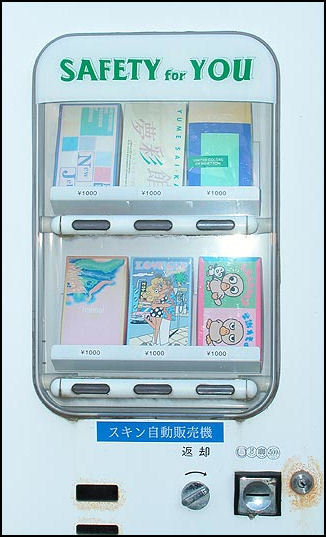

condom vending machine Among Japanese that use birth control, 80 percent use condoms, followed by the rhythm method and spermicide jelly. Some use female contraceptives (a cookie-size, thin piece of plastic with a spermicide). Sterilization is practiced among couples that already have kids. Many Japanese don't use contraceptives as illustrated by the high number of shotgun weddings.

Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki wrote in the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: Japan has consistently maintained one of the world’s lowest incidence of out-of-wedlock births, well below 5 percent (Lewin 1995). A 1995 study by the Population Council, an international nonprofit New York-based group, reported that only 1.1 percent of Japanese births are to unwed mothers, a figure that has been virtually unchanged for twenty-five years. In the United States, this figure is 30.1 percent.

Japanese birth control policy has often been determined by politics. Abortions were banned in 1907 and all kinds of birth control were made illegal in World War II. In the 1950s, when the population was growing rapidly and women were added in the labor force, abortion were legalized for "economic and health" reasons.

Single women are reluctant to visit gynecologists because of the widespread assumption that only reason a single woman would do so would be to obtain an abortion or receive treatment for a sexually transmitted disease. Single women become painfully aware of these assumptions if they are in awaiting room surrounded by pregnant or married women.

Good Websites and Sources: Blog Report on Birth Control in Japan myso-calledjapaneselife.blogspot.com ; 2009 Japan Times Article japantimes.co.jp ; New York Times 1999 Article on Viagra Versus Birth Control Pills nytimes.com ; Links in this Website: POPULATION OF JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BIRTH CONTROL IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PEOPLE, RACE, AND PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Contraception in Japan

▪Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki wrote in the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: Various contraceptive devices became available in the democratic days after the war, including use of the pessary (diaphragm), contraceptive jelly and foams, etc. Nearly 80 percent of Japanese people still choose the condom as their most favorable contraceptive device. This choice, however, is conditioned by the government’s near-total ban on the oral contraceptive pill. [Source: Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki Encyclopedia of Sexuality, 1997 ++]

Even married women tend not to discuss contraceptives openly with their husbands. Traditionally, Japanese men are accustomed to taking the lead in relationships, especially when it comes to sex. Japanese women frequently express their awe at the independence of American women who make their own decision to use the pill. Nevertheless, after decades of public and national administration debate, approval of the OCP may be expected in the near future (WuDunn 1996). ++

Japanese contraceptive practices naturally reflect this limitation. According to the latest statistics, 77.7 percent of contracepting Japanese use a condom; one in five, 21 percent, use the Ogino method/rhythm method/BBT method; 7.1 percent use withdrawal (coitus interruptus), 7 percent rely on surgical sterilization, and 3.7 percent on the intrauterine device. The rather high popularity of condom usage among the Japanese people is due to the strong policy of the Imperial Army Administration throughout the militarist period, when it was consistently used to prevent various venereal diseases. ++

Margaret Sanger (1883-1966), the American nurse who eventually organized the International Federation of Birth Control, visited Japan early in the Showa Era, the late 1920s, to promote the birth control movement in Japan. At the time, the national administration disliked this idea because of its own policy of promoting childbirth for national security reasons. Thus, the government publicly opposed the birth control movement. Nevertheless, because the military widely promoted use of the condom for prevention of venereal diseases, it eventually was firmly accepted by the common people in Japan as an effective method of birth control. Later, in the post-World War II years, this positive attitude of the Japanese people toward the condom functioned effectively in promoting the family planning movement. ++

Condoms are often sold to housewives by door-to-door “skin ladies.” In 1990, moralists were disturbed when, after a marked increase in teen abortions, a condom company targeted the teenage market with condom packets bearing pictures of two cute little pigs or other cartoon animals and names like “Bubu Friend” (Bornoff 1991, 337). ++

The greatest obstacle in Japan to contraception is the national control of the contraceptive pill (OCP). In the 1970s, the promoters of feminism were openly against induced abortion and thus started a movement to make the OCP available. However, when they recognized that high-dosage OCPs had side effects, they changed their position and strongly opposed its free use. As is widely known now, the majority of current low-dosage OCPs pose little danger. Consequently, some of the current feminist promoters in Japan are not against expansion of choices by making low-dosage OCPs widely available. Nevertheless, the great majority of Japanese feminists still maintain their skepticism about the use of OCPs. ++

Birth Control Pills in Japan

Birth control pills were finally approved in Japan in May 1999, nearly 50 years after they were approved the United States. Before then only high-dose varieties of the pill were available and they were prescribed for menstrual disorders not birth control. These pills carry a higher risk of high blood pressure and some forms of cancer than the low dose versions.

Over the years the Japanese government has supported the ban on the pill on the grounds of sexual morality, AIDS prevention and women's health. Critics have claimed the pill encourages promiscuity, produces side effects such as morning sickness, bloating and strokes and pollutes rivers with hormones. Among the groups opposed to the legalization of birth-control pills were condom makers and health clinics that performed abortions.

One of the main reasons approval of birth control pills was finally granted was the outcry over the fact that Viagra was approved with a minimum of fuss by the Japanese-equivalent of the FDA in 1998 after a review process that took only six months while birth control pill had been under review for nine years and remained unavailable 34 years after regulatory approval was first requested. Many women felt there was clearly a double standard. It was said that Viagra was approved so quickly because members of Parliament?mostly old men?wanted to get their hands on the drug.

Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki wrote in the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: As of January 1997, only a medium-strength form of the pill was available in Japan for medical (non-contraceptive) purposes. However, some women were using it as a substitute for the low-dose contraceptive pill normally taken by American and European women. Originally, the Ministry of Health and Welfare cited the possible link between the hormonal pill (OCP) and cardiovascular disease, weakened immunity, cervical cancer, and thrombosis as its reason for not approving distribution of the pill in Japan. ++

In 1996, new research studies undermined this objection, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare gave signs that it might remove its over three-decade-old ban on the OCP, perhaps even by the end of 1997. The Ministry admitted to some continuing concerns about removing the ban. There is a fear that, with the birthrate at 1.4 live births per woman, pushing the OCP might drop the birthrate even lower. More realistic is the fear that use of the OCP rather than the condom would increase the spread of AIDS among those who use the pill. More basic to the cultural values of Japanese men and women is the fear that Government approval of the OCP may send a signal of promiscuity and upset the delicate dynamics in male-female relationships. ++

Aversion to Birth Control Pills in Japan

bloody-type condom

vending machine It was thought that after the pill was legalized, Japanese women would jump at the change to take it. That has not happened. As of 2004, five years after they were legalized, Japanese women continue to shun birth control pills. According to one survey only 1.3 percent of the Japanese females between 15 and 49 used the pill, compared to 15.6 percent in the United States. More than 70 percent the women surveyed said they would never use the pill. Only 20 percent said they world try it.

The number of women using birth control pills increased from 200,000 in 2001 to 600,000 in 2009 but that still was only 3 percent of women between 16 and 49. In France 44 percent of women that age use the pill. In Britain 18 percent do. In a survey by the Tokyo University Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, more than half of those who said they wouldn’t use the pill said they wouldn’t because they were “concerned about side effects.”

Reasons why Japanese women avoid the pill, experts say, include ignorance, easy-to-obtain abortions, marketing restrictions, discriminatory pricing and taboos associated with visiting a gynecologist. A month’s supply of birth control pills cost around $30 but women who want the pill sometimes have or pay a $1,000 a year for the pills and extensive tests required to get a prescription.

Many women fear they will gain weight, become infertile, or suffer some other side effect. One woman told the Los Angeles Times, "I hear women can't get pregnant again, even after they stop using it." Another said, "It's much cheaper and easier just to ask men to but condoms. Taking something everyday seems like a real bother."

On the social stigmas attached to birth control pills, one Japanese psychiatrist told Newsweek, "Many women still say, my boyfriend would think I play around if I talked about birth control." One Japanese gynecologist said, "It's easier for a Japanese woman to say she's had an abortion that to say she's on the pill."

Condoms in Japan

Condomania shop Condoms are the most common form of birth control. According to a United Nation study, they are used regularly by 46 percent of couples between the ages of 15 and 49 and by 80 percent of the sexually active public who use birth control.

.

One reasons they are so popular is that they are easy to obtain with a minimum of fuss and embarrassment. Condoms are sold at all kinds of stores and can be purchased discreetly from vending machines. Condomania in Tokyo sells Skinless Wrinkle Zero-0 condoms and glodoms" that "light up your love life." Sometimes female salespersons sell them door-to-door in respectable neighborhoods.

Condom use is linked with low teenage pregnancy, low HIV and sexually transmitted disease rates. Widespread use of condoms dates back to World War II when Japanese soldiers in foreign lands were required to use them when the visited prostitutes. Women often insist that men wear condoms and the men comply.

Abortion in Japan

Abortion has been an accepted form of birth control for centuries in Japan. At least one out of three Japanese women has had an abortion. The number of legal abortions has declined from about 460,000, about one abortion for every two live births, in 1990 to 330,000 in 2002.

About 52 percent of pregnancies are unwanted (compared to 30 percent in the United States). Abortions cost about $1,000 in Japan and are not covered by health insurance. They have been legal and free of controversy since 1948.

An informal survey at a provincial university found that about 10 percent of the female students has had an abortion. Buddhist temples contain "abortion cemeteries," rows of little stone figures, often dressed in miniature clothes, honoring children who were never born. Small toys and fruit are often placed outside the glass case holding the small statues to placate the spirits of the lost infants.

The number of abortions of embryos and fetuses believed to have been carried out after abnormalities were discovered during prenatal examinations doubled in the 10 years from 2000, compared to the previous 10 years, a survey has revealed. Ultrasound scanning in recent years can detect chromosomal abnormalities and other abnormalities in the early stages of pregnancy, when abortions are relatively safe. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun , July 23, 2011]

According to the survey, carried out by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 11,706 embryos and fetuses were aborted from 2000 to 2009 on indications that they were affected by Down syndrome, fetal hydrops--abnormal accumulation of fluid in the abdomen or chest--and other serious conditions. The number is 2.2 times more than the 5,381 abortions carried out for such reasons from 1990 to 1999. The survey's results were compiled by Fumiki Hirahara, a professor at Yokohama City University and director of the university's ICBDSR (International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research).

History of Abortion in Japan

Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki wrote in the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: The national policy of Japan after the Meiji Era, when Japan’s modern national structure emerged, was to strengthen the nation. Thus children were considered to be the treasure of the nation, and abortion was naturally deemed illegal. [Source: Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki Encyclopedia of Sexuality, 1997 ++]

With the rebounding of the post-World War II social order, the Eugenic Protection Law was implemented in 1948, and induced abortion became a fully legal and allowed method of birth control in Japan. The law set out certain premises to be satisfied for abortion to be permitted, but many accepted it quite readily. Thus induced abortion became the most popular method of family planning in Japan in the mid-1950s, with 1.2 million abortions a year, an extremely high rate of 50.2 per 1,000 women annually. Later, the rate and the number of the induced abortions declined rapidly, dropping from 1.1 million cases in 1960, to 730,000 cases in 1970, and 457,000 cases in 1990. By 1990, the abortion rate was 14.9 per 1,000 women a year, less than a third of the rate of forty years ago. This significant and important change came about because of the special effort of advocates of a sound family planning movement and the increased use of condoms. It should be noted that this reduction in abortion and the popularization of family planning were achieved despite the unavailability of the oral contraceptive pill and a quite low IUD usage rate. ++

Even though the current rate of induced abortion is becoming acceptably low, there are still disturbing elements in the statistics, mainly a gradual increase of abortion among teenage youths. In the 1970s, the total number of abortions for teenage pregnancy was approximately 13,000. This number increased to 14,300 in 1970,19,000 in 1980, and 29,700 in 1990. The rates of abortion among women under 20 years of age increased as follows: 3.2 per 1,000 in 1960 and 1970, 4.7 per 1,000 in 1980, and 6.6 per 1,000 in 1990. Keeping in mind that the sexual activity of young people in this nation is increasing, it is apparent that more efficient education of the youth for pregnancy prevention is strongly needed. For one thing, sex education within the public education system is far from being well developed in this country. The traditional value systems about sex and sexuality, such as the theory of purity education that prohibits and condemns premarital sexual activities as a crime, for example, creates burdens for the young people, even though two thirds of them accept premarital relations. Such beliefs often affect the sexual behavior of the young and interfere with their acquisition of knowledge and skills about pregnancy prevention. ++

Japan has no debate over the morality of abortion, and no politicians taking political stands for or against abortion In fact, virtually everyone believes that abortion is each woman’s own private business. Despite this wide acceptance of abortion, there is an ambivalence about abortion among many Japanese women and men that reflects the dualism one finds throughout Japanese sexual attitudes. At Buddhist temples around the country, one finds galleries of hundreds, even thousands of tiny memorial statues dedicated to aborted fetuses, miscarried and stillborn babies, and those who died as infants. These mizuko jizo are dressed and visited regularly, sometimes monthly, by Japanese women who have had an abortion or lost a baby, and feel a need to atone for their loss. Japanese women, and sometimes men, visit their mizuko jizo to express their grief, fears, confusions, and hopes of forgiveness for ending a human life so early, however rational and necessary that decision may have been. ++

The concept of the mizuko jizo did not develop until after World War II and has since been linked more and more with abortion rather than miscarriages, stillbirths, or infant deaths. Even some gynecologists who perform abortions regularly visit the temples to purify themselves in a special Buddhist ritual. In former times, fetuses and even newborns were not believed to be fully human or have a spirit or soul until the newborn was ritually accepted into its family and linked with its ancestors, so abortion and even infanticide was accepted matter of factly. The recent tradition of the mizuko jizo appears to satisfy many of the emotions and feeling traditional suppressed in the acceptance of abortion (WuDunn 1996). ++

History of Population Control in Japan

Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki wrote in the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: From ancient times, population control, particularly in each village community, has been maintained publicly perhaps as part of the wisdom of the public welfare. In premodern days, the actual method often involved certain techniques related to primitive religions and/or incantations “turning childbirth changing into stillbirth.” What in Western culture is termed infanticide was not necessarily considered illegal or unreasonable according to the faith and/or ethics of that era. According to authentic ancient belief and practice, the baby belongs to God until the very moment of its first cry. Therefore, suffocating the newborn before it cried, before it was “really born,” and returning the incipient life to God was not considered wrong. Western culture would consider this culpable infanticide, but such was not the case in ancient Japanese beliefs; see the discussion of abortion and mizuko jizo in the preceding paragraph. [Similarly, in many regions of China, a newborn infant is not considered “fully born” and human until the whole family gathers three days after the infant’s birth to celebrate its “social birth” and official recognition by the family’s patriarch and, through him, by the whole family and their ancestors. (Editor)] [Source: Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki Encyclopedia of Sexuality, 1997 ++]

By 1995 the Japanese government had become so concerned about its plunging birthrate - 1.53 per woman and declining - that the Institute of Population Problems, a part of Tokyo’s Health and Welfare Ministry, sent out questionnaires to 13,000 single Japanese citizens asking them what they thought about marriage, families, and children. In view of the plunging birthrate and a heating up of the war of the sexes, Japan is facing a demographic time bomb. As the population ages and the birthrate shrinks, the tax burden on the Japanese work force will rise. Economists also suggest that Japan’s famously high rate of savings will increasingly have to support its retired population, and not factories and other productive investments (Itoi and Powell 1992). ++

With its birthrate plunging to 1.4 in 1996 - Tokyo’s birthrate was 1.1 - Government projections suggested that within a hundred years, by 2100, Japan’s population will tumble to 55 million, from 125 million today. That would be the same population Japan had in 1920. At 55 million, Japan would have a population density five times that of the United States today, but its position as a global power would certainly be reduced, when in 2050 Japan’s population drops to just one quarter of America’s projected population. By the year 3000, it could drop to 45,000, according to a weekly magazine projection. ++

To counteract this trend, many Japanese cities are paying women residents a bonus, up to $5,000, when they have a fourth baby. Among the other incentives being considered are: cash upon marriage, cut-rate land for child-bearing couples, importing Philippine women of marriageable age, and cash grants to parents when their children turn 3, 5, and 7, which are all auspicious birthdays in Japan. Because of the discouraging cost of childrearing, some have recommended an annual financial bonus. In 1995, when Prime Minister Hashimoto was Finance Minister, he suggested a novel way of encouraging fertility: discourage women from going to college.

Image Sources: Japan Visitor, Photomann

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2013