TARSIERS

Tarsiers (Tarsiidaetarsiers) are bizarre, lemur-like primates. About the size of al chipmunk and the same basic shape of an African bush and found only in the rainforests and jungles of Borneo, Indonesia and the Philippines, they have enormous eyes and a gremlin-like smile and can rotate their head nearly 360̊. They forage for food at night and are particularly fond of eating cockroaches Tarsiers are found only in some rainforest in some parts of the Philippines and Indonesia.

There are 13 living species of tarsier, all in the genus Tarsius, nearly all of them in Indonesia, primarily Sulawesi. Similar in size, morphology, and ecology, members of all tarsier species are all small, nocturnal (active at night), predatory primates known for their leaping and clinging abilities. They prefer secondary forests and mangroves with dense vegetation rather than canopied primary forests. The longest reported lifespan for a tarsier in captivity is over 17 years. The oldest individual caught in the wild was estimated to be 10 years old. Tarsiers change their behavior due to old age between 14 and 16 years of age. Signs of advanced aging may include graying of hair around the face and dental wear. For most tarsier species there are healthy numbers. The biggest threats to tarsiers are deforestation, habitat loss and capture by humans. [Source: Sabrina Archuleta, Animal Diversity Web (ADW

Tarsiers are named after their tarsal bones — two greatly elongated bones on their feet. These extra bones give tarsiers added leverage for jumping. Even though they are the size of rats they can leap 1.2 to 1.8 meters (four to six feet) in a single jump. The Dayaks of Borneo call tarsiers “hantu”, ancestral spirits. In the past, they were used as a totem animal of the head-hunting by Iban people of Borneo. Some scientist argue that they are prosimians like lemurs and lorises but others say they more closely related to monkeys and apes. Tarsiers are similar to lemurs but have different nose structures (a dry nose) and lack the reflective material behind the iris that lemurs have. Monkeys also share these traits. The olfactory and sight-related structures of tarsier skulls is similar to that of monkeys. Some scientist view them as missing links between lemurs and monkeys. The name tarsier refers to the tarsier’s elongated tarsal, or ankle, region.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SPECTRAL TARSIERS factsanddetails.com ;

TARSIERS: CHARACTERISTICS, TAXONOMY, FOOD factsanddetails.com ;

TARSIER BEHAVIOR: SOCIALIZING, MOBBING AND MATING factsanddetails.com ;

PHILIPPINE TARSIERS factsanddetails.com

PRIMATES: HISTORY, TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com ;

MONKEY TYPES: OLD AND NEW WORLD, LEAF- AND FRUIT-EATING factsanddetails.com ;

MAMMALS: HAIR, CHARACTERISTICS, WARM-BLOODEDNESS factsanddetails.com

Sangihe Tarsiers

Sangihe tarsiers(Tarsius sangirensis) live on subtropical-tropical Sangihe Island of North Sulawesi, which is a small island approximately 576 square kilometers in area and situated east of the Caleb Sea and southwest of Philippine Sea on the eastern side of Indonesia. Sangihe has a climate with a dry and wet season. The tarsiers are normally found in groups of two to six living on coconut trees, bamboo, vines, and brush in limited patches of forest, shrubs, and wetlands around agricultural areas, farms and villages. Before human disturbance the animals occupied the island’s primary forests, which are now largely gone. Sangihe tarsier are considered a lowland species. [Source: Miriam Minich, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Regarded as subspecies of spectral tarsier until 2008 but now ar considered a distinct species, Sangihe tarsiers range in weight from 120 to 160 grams (4.2 to 5.6 ounces) and their head and body range in length from 12 to 13 centimeters (4.72 to 5.12 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Like other tarsiers, they have large bulging eyes and bat-like ears. They have short coat that is golden brown, black ot grey in color with some white spots located on the stomach. Their scaly tail, approximately 30 centimeters long, more than twice as long as their body. Because tarsiers normally cling vertically to branches and trees, they have long, cushioned palm and fingers for holding on. Sangihe tarsiers are known for their large skulls and having the longest tails of all tarsier species. They are also known having less woolly fur than other tarsier species.

Tarsiers mostly forage on insects and occasionally birds and lizards.Sangihe tarsiers have been observed foraging in groups. In captivity, individual tarsiers have been reported eating a diet consisting of 48 percent crickets, 24 percent worms, 24 percent grasshoppers, and four percent geckos — consuming about 10 to 12 grams of food a day. Their main known predators are humans, feral cats, snakes, Asian palm civets and birds of prey.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Sangihe tarsiers are listed as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Local people sometimes trade and eat these tarsiers as bush meat.

Sangihe Tarsier Behavior, Communication and Reproduction

Sangihe tarsiers are arboreal (live mainly in trees), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Tarsiers generally socialize and forage in groups. Typically social groups are made up of on male and a few females with their offspring. They reside and sleep mostly in trees and spend their nights scavenging for food in groups, mostly feeding on insects and small prey while clinging to trees and branches. The home range of the Sangihe tarsier has not been demarcated but they have been recorded to make nightly paths which range from 1119 to 1636 meters per individual.

Sangihe tarsiers sense using touch, sound and chemicals detected by smelling and communicate with pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species), scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them) and sound, using duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds). In the early mornings and late evenings, male and female Sangihe tarsiers communicate through mating calls. Females call out two-note, whistle sounds while males reply with a single-note chirping sound. Sangihe tarsiers are different than other species of tarsiers in that males in that males and female typically produce only one-noted or two-noted sounds. Their duets are repeated multiple times, females having a whistle note while males have a chirping note. When they feel threatened they also make sounds. Sangihe tarsiers have a lingering scent that they use to communicate and define their territories. This scent is unique to each tarsier. and employ

Sangihe tarsiers are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). Adults usually live with their mate and are monogamous, but some live in a group where one male mates with a few females. The presence of polygynandrous activities in tarsier group often depends on the structure and number of individuals in a population.

Tarsiers breed once a year, sometimes twice a year. Seasonal changes in the Sangihe islands are minimal so tarsiers mate year-round. Most female Sangihe tarsiers mate and have a single offspring each year. At birth, offspring are approximately 25 percent of female weight. The female tends to leave the young at night in a hidden area while she feeds. The gestational period of Sangihe tarsier’ is not known but it may be similar to that of spectral tarsier, which is about six months. The average weaning age is 80 days. Female tarsiers typically become sexually mature at 2.5 years of age. Females are the primary caregivers of offspring. Among their duties are carrying, feeding and grooming. Males mainly play the role of protectors but have been observed occasionally carrying and grooming young. Offspring tend to stay in the social group of the parents after they become independent.

Horsfield's Tarsiers

Horsfield's tarsiers (Tarsius bancanus) are also called western tarsiers. They live in primary and secondary forests of hilly lowlands and swampy plains in Borneo and southern Sumatra as well as on several smaller islands. Its range Sumatra, is restricted in the north by the Musi River. Although they prefer primary and secondary forest they can also be found in mangroves, fruit plantations and forest edges. They are a vertical clingers and leapers, and thus generally do not venture into open areas unless both prey and small-diameter trees to cling to are present. Although they are described as a lowland species, residing below 100 meters in elevation, they have been sighted above 1,200 meters ((3937 feet). It has been estimated that Horsfield's tarsiers have a lifespan of 12 years in the wild. [Source: Paul McKeighan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Horsfield's tarsiers weigh 86 to 135 grams (3 to 4.8 ounces) and measure 12.1 to 15.4 centimeters (4.8 to 6.1 inches) from head to foot. Their average length is 12.9 centimeters (five inches). Their tail is 18.1 to 22.4 centimeters (7.1 to 8.8 inches) long. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. They are about 10 grams heavier than female [Source: Canon advertisement in November 2011 National Geographic; [Source: Paul McKeighan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]]

Horsfield's tarsiers have huge eyeballs. A single eyeball is larger than its brain. They can also turn their head 180 degrees like an owl. Their upper vertebrae are modified to allow their head to rotate like this. Their fur is grey and/or brown. Their tail is nearly twice as long as its head and body and has a tuft of hair near the end. Like all tarsiers they have long hind legs — the longest of any mammal in proportion to body length — which contributes to their extraordinary leaping ability. The forelimbs are mushc shorter. All four limbs end in long, thin digits. The front digits have disc-like pads. /=\

Horsfield's tarsiers are carnivorous and mainly eat insects of almost every kind and have been observed consuming small vertebrates, including birds, mammals and reptiles an even prey as large as themselves such as a spotted-winged fruit bats tangled in mist nets. Their main known predators are slow lorises. The Horsfield's tarsier’ brown-grey no doubt provides them with at least some camouflage and helps decrease risk of predation. Perhaps they are most vulnerable when they are chewing and can’t hear approaching predators.

The number of Horsfield's tarsier is unknown but their habitat is threatened by logging and palm oil plantations. They are classified as "vulnerable" on the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species, primarily due to a 30 percent habitat loss in the 1990s and 2000s. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Some tarsiers are collected for the illegal pet trade. They may be killed because they are regarded as agricultural pests. They appears to be especially vulnerable to contamination from agricultural pesticides.

Horsfield's Tarsier Behavior and Communication

Horsfield's tarsiers are arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (able to or good at climbing), saltatorial nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range). They determined hunters, consuming one-tenth of their body weight each night and using sound to locate prey such as insects, spiders and other arachnids and small animals. It captures many kinds of prey by leaping on them and is capable of covering 45 times its body length (almost six meters0 in a single pounce. The size of their range territory is .045 to .1125 square kilometers, with their average territory size being .085 square kilometers. Male territories tend to be slightly larger than those of females. Radio-telemetry data of Horsfield's tarsiers showed that males traveled farther during the night than females. [Source:Paul McKeighan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Paul McKeighan wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Horsfield's tarsiers are vertical clingers and leapers. They use their tail and hind limbs to support themselves on vertical surfaces, normally saplings. They strongly prefer trees with trunks smaller than four centimeters in diameter, with the majority being about two centimeters. Leaping makes up the majority of their locomotion, and they spend only five percent of their time on the ground. They prefer prey that are on tree trunks rather than on the ground, where the tarsier are is less mobile. Regardless of the prey, they return to a tree to perch and consume it.

Horsfield's tarsiers are are most active in the hours immediately after dusk. The tarsier's gigantic eyes allow it to hunt at night. Differing from other tarsiers, the Horsfield's tarsier is quite solitary, coming in contact with other members of its species only for mating, establishing territory, or raising young. They often return to the same general area to sleep, if not to the same perch. They tend to hunt within one meter of the ground, and sleeping perches are usually found on a vertical or near-vertical structure over four meters high.

Horsfield's tarsiers sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with touch, sound and chemicals detected by smelling and pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Horsfield's tarsiers relies mostly on sight for foraging and depends upon sound and smell for intraspecific communication. Of all tarsier species, Horsfield's tarsiers is the least communicative. Where touching and grooming are common in most other species, it has only been documented between mothers with young and mating pairs. Territory is marked with urine, scent from glands in the ano-genital region, and secretions from the epigastric gland. Horsfield's tarsiers communicates with potential mates via squeaks and whistles, and physical contact prior to copulation is usually initiated by grasping the tail.

Horsfield's Tarsier Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Horsfield's tarsiers are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). It had previously assumed that tarsiers, including Horsfield's tarsiers, were monogomous. According to to Animal Diversity Web: However, recent evidence suggests that the mating system is highly dependent on prey availability, and that Horsfield's tarsiers is most likely polygynous. Females signal their readiness to mate both chemically and visually. When in estrus, females exhibit labial swelling and scent-rubbing near territorial (defend an area within the home range), borders shared with males. Once males identify estrous females, the often perform "courtship calls."

Horsfield's tarsiers engage in year-round breeding. Mating is nonseasonal. They tend to have slightly more than one birth per year, with an average inter-birth period being 258 days. The average gestation period is 178 days. The average number of offspring is one. Offspring can be up to 25 percent of the mother body weight. Horsfield's tarsiers are moderately precocial at birth, as they are able to climb but not leap. Most young are weaned by 80 days after birth. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at about 2.7 years.

After birth male Horsfield's tarsiers are aggressively chased away by the mother until the baby reaches maturity perhaps out of fear of infanticide. Captive males sometimes kill their young. Young do not develop locomotor independence until about four weeks; until then, they are "parked" while mothers forage for prey. Unlike many other primates, mother's rarely carry young, which may be due to the large-size of newborns. Other than providing milk and protection from the father, mothers offer limited care to their offspring.

Pygmy Tarsiers

Pygmy tarsiers (Tarsius pumilus) live in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia in cloud forests at elevations between 1800 and 2200 (5905 to 7218 feet), at an average elevation of 2100 meters (6890 feet). The cloud forest where they is often shrouded in dense mist. Humidity in these regions is 85 to 100 percent. It is a cold and wet environment. Moss-covered conifer forest predominates at elevations between 1900 and 2000 meters where they live. Above this elevation, the canopy is only 10 to 20 meters high, tree trunks are not buttressed, leaves are small, large woody vines are absent, and species diversity of trees and plants is lower than in lowland tropical rainforest. Pygmy tarsiers often reside in the lower canopy, among sapling trunks, and on the forest floor. [Source: Trevor Ford, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Pygmy tarsiers were first described by Miller and Hollister in 1921 and were first classified as a subspecies of Spectral tarsiers. They are is now recognized as a separate species. Pygmy tarsiers are mainly insectivores (mainly eat insects) but also eat non-insect arthropods and occasional. birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles. Their main prey is insects heavily keratinized exoskeletons. Larger arthropods are less abundant at higher altitudes. Pygmy tarsiers drink water by lapping.

In 2008, on a misty mountaintop on Sulawesi, scientists for the first time in more than 80 years observed living pygmy tarsier. Reuters reported: Over a two-month period, the scientists used nets to trap three pygmy tarsiers — two males and one female — on Mt. Rore Katimbo in Lore Lindu National Park in central Sulawesi, the researchers said. They spotted a fourth one that got away. The tarsiers, which some scientists believed were extinct, may not have been overly thrilled to be found. One of them chomped Sharon Gursky-Doyen, a Texas A&M University professor of anthropology who took part in the expedition. ““I’m the only person in the world to ever be bitten by a pygmy tarsier,” Gursky-Doyen said in a telephone interview. “My assistant was trying to hold him still while I was attaching a radio collar around its neck. It’s very hard to hold them because they can turn their heads around 180 degrees. As I’m trying to close the radio collar, he turned his head and nipped my finger. And I yanked it and I was bleeding.” [Source: Reuters, November 18, 2008]

“The collars were being attached so the tarsiers’ movements could be tracked. They had not been seen alive by scientists since 1921. In 2000, Indonesian scientists who were trapping rats in the Sulawesi highlands accidentally trapped and killed a pygmy tarsier. “Until that time, everyone really didn’t believe that they existed because people had been going out looking for them for decades and nobody had seen them or heard them,” Gursky-Doyen said. Her group observed the first live pygmy tarsier in August at an elevation of about 2,100 meters. “Everything was covered in moss and the clouds are right at the top of that mountain. It’s always very, very foggy, very, very dense. It’s cold up there. When you’re one degree from the equator, you expect to be hot. You don’t expect to be shivering most of the time. That’s what we were doing,” she said.

The number of pygmy tarsiers and how seriously they might be endangered is not known. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Data Deficient. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Most of what is known about them is from a few museum specimens and one wild group. However, it is assumed that pygmy tarsier populations are small, fragmented and declining. Deforestation and loss of habitat due but their habitat is remote habitat and thus far seen only small-scale human expansion. The open canopy cover of the highland montane forests where pygmy tarsiers live and their small size makes them vulnerable to raptor attacks.

Pygmy Tarsier Characteristics

Pygmy tarsiers range in weight from 48 to 52 grams (1.7 to 1.8 ounces) and range in length from eight to 11 centimeters (3.2 to 4.4 inches), with their average length being 9.6 centimeters (3.78 inches). Like other tarsiers, pygmy tarsiers have large round eyes, large bare ears, long hind limbs with elongated ankles, elongated digits, and a long slender tail. They are most easily distinguished from other tarsiers by their small body size, which is about half that of lowland tarsier species. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. [Source: Trevor Ford, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW): Pygmy tarsiers are similiar in overall appearance to spectral tarsiers, of which they were once considered a subspecies. The fur of pygmy tarsiers is silky and is longer and denser than that of spectral tarsiers. They are red-brown in color, although pygmy tarsiers occasionally lack the buff colored post-auricular spot common among spectral tarsiers. The underbelly of pygmy tarsiers is buff, grayish, or slate colored. Hair on the face is usually shorter than hair on the rest of the body. Pygmy tarsiers have a rounded head with a short snout. Their ears are relatively smaller than those of other tarsiers, and the degree of orbital enlargement is smaller than other species. Their eyes are approximately 16 millimeters in diameter. Members of this species have a long slender tail. Approximately one third of the ventral surface of the tail is scaly, which is attributed to its function in body posture. The tail is heavily haired and is dark brown or black in color. The tip of the tail bears a tuft of hair. /=\

Pygmy tarsiers, like, spectral tarsiers, have short fore limbs and small hands, suggesting that these animals use their hands more for locomotion than for immobilizing prey, as do other tarsier species. Pygmy tarsiers have several distinctive morphological characteristics that may stem from their unique highland habitat. Their body proportions differ considerably from lowland tarsiers. Pygmy tarsiers have a longer tail relative to head-body length and longer thighs relative to overall hind limb length, Despite their smaller overall size, absolute thigh length is still comparable to that of other Sulawesian tarsiers. These qualities are advantageous for leaping great distances between trees in thin forest cover. The small size of pygmy tarsiers may be an adaptation to the cooler, less productive highland environment. Although most tarsiers have low basal metabolic rates, pygmy tarsiers may have increased metabolic rates due to their small size and cold habitat. /=\

Although most tarsiers have reduced nails that do not extend past the digital pads, pygmy tarsiers have nails on all five digits of the hand, including the big toe, and on the two lateral digits of the foot. These nails extend beyond the edge of the digital pads, are laterally compressed, and are sharply pointed at the tips, resembling claws. The digital pads on both their hands and feet are reduced in size. Both their claw-like nails and reduced pads are thought to provide a better grasp on the mossy substrate to which they cling during feeding and locomotion.

Pygmy Tarsier Behavior

Pygmy tarsiers are arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (able to or good at climbing), saltatorial (adapted to leaping), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). The size of their range territory is around hectares. Males and females exhibit different patterns of travel, and males are difficult to track. [Source: Trevor Ford, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: In the dense vegetation of their habitat, pygmy tarsiers spend most of the day sleeping on vertical branches or possibly in hollow trees. When clinging to a vertical branch, they often use their tail to brace themselves against the vertical support and to support their body. The head of pygmy tarsiers tends to drop downward between the shoulders when sleeping. If disturbed while resting, these animals may move up and down the vertical support with the face presented towards the threat, mouth open, and teeth bared. When waking, pygmy tarsiers continuously furl or crinkle their ears. /=\

Tarsiers spend much of their time scanning for prey from low positions on tree trunks. Although they do not build nests, they may return to the same tree to sleep. Preferred sleeping trees are large, and scarcity of large trees at high altitudes may restrict the number of possible sleeping sites for this species. /=\ Pygmy tarsiers have a wide field of vision and can rotate their head nearly 360 degrees. They can leap several meters from tree to tree, and their leaps tend to be froglike. On a flat surface, they can leap from 1.2 to 1.7 meters long and up to 0.6 meters high. When leaping, their tail is arched over their back. When walking on all fours, however, the tail hangs down. /=\

Only one group of pygmy tarsiers has been observed in the wild. This group consisted of one adult female and two adult males, which is unusual for Tarsius. Lowland Sulawesian tarsiers usually live in family groups of one adult male, one to two adult females, and offspring, though group size varies with resource availability and other ecological factors. Social group composition of pygmy tarsiers may be a result of ecological constraints unique to their high-altitude habitat, which alters the dynamics of group living. The population density of pygmy tarsiers also appears to be much lower than that of other tarsiers, as indicated by the historical difficulty in finding individuals to confirm the continued existence of the species. A 3-month survey found only three individuals in 60 nights of attempted trapping, whereas in another 3-month survey, 100 spectral tarsiers were recorded. /=\

Spectral tarsiers, and possibly pygmy tarsiers, are territorial (defend an area within the home range). Spectral tarsiers actively chase others out of their home range and mark their core areas by rubbing the branches with urine and epigastric glands.

Pygmy Tarsier Communication and Reproduction

Pygmy tarsier sense and communicate using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. They employ duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds), choruses (joint displays, usually with sounds, by individuals of the same or different species) and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. [Source:Trevor Ford, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Trevor Ford wrote in Animal Diversity: Tarsiers commonly communicate through vocalizations and urine scent marking. However, each of these is observed much less frequently among pygmy tarsiers than other species. The infrequency of observed scent marking in this species, however, may be due to difficulty in monitoring canopy habitat and high rainfall quickly washing away urine. The auditory bullae of pygmy tarsiers are more enlarged than those of other tarsiers, perhaps because the heavy fog and thick moss cover common in their habitat tend to reduce sound travel. However, vocal communication is markedly reduced in pygmy tarsiers. They rarely perform the male-female vocal duets or family choruses typical of lowland species. Because these vocalizations are associated with territory maintenance, this could indicate that pygmy tarsiers are less territorial (defend an area within the home range), than lowland species, or that they make use other means of communication to communication the same information. /=\

Little is known about the mating systems of pygmy tarsiers. Spectral tarsiers, their closest relative. are usually monogamous but some groups engage in polygyny. It is likely that reproductive behavior of pygmy tarsiers resembles that of other tarsiers. Spectral tarsiers have two breeding seasons annually, about six months apart — at the beginning of the rainy season, and at the end of the rainy season. Births in spectral tarsiers occur in May and from November to December. /=\

Pygmy tarsiers likely have a long gestation period of around six months and produce only one offspring per year. With tarsiers in general, young are born fully furred and well-developed and cling to the mother or or are carried in the mouth. They can leap at about one month of age and can capture prey at approximately 42 days of age. Weaning is thought to occur shortly afterward. In closely related spectral tarsiers, parental care is primarily maternal. Some allocare is exhibited by subadult females, and much less so by adult and subadult males, relatively little compared to other primates.

Dian’s Tarsiers

Dian's tarsier(Tarsius dentatus) lives in primary and secondary lowland rainforests in northern part of Sulawesi at elevations from 1000 to 1500 meters (3920 to 4920 feet). First described as a new species in 1921 by Miller and Hollister, their presence has largely determined by their vocalizations and they are primarily known to live in Morowali Nature Reserve and Lore Lindu National Park. Dian’s tarsier has 46 chromosomes made of five pairs of acrocentric chromosomes and 17 meta- or submetacentric pairs, whereas Philippine tarsiers has 80 chromosomes made of seven meta- or submetacentric pairs and 33 acrocentric chromosomal pairs. [Source: Liubin Yang, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Like all tarsiers,Dian's tarsier are primarily insectivores who hunt crickets, grasshoppers, moths other insects and occasionally small lizards and crustaceans, such as shrimps, Field studies indicate the population density of Dian’s tarsier varies from 129 to 136 individuals per square kilometer. At an altitude of 500 to 1000 meters, population density is estimated to be 180 individuals, while at 1000 to 1500 meters only 57 individuals per square kilometer were observed. The population was also approximately ten times more dense in secondary forests than primary forests.

Dian’s tarsier is categorized as a relatively low risk of being endangered on several conservation lists because of their ability to adjust to disturbed habitats, and because they reside in large, protected parks. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Dian's tarsier are listed as Vulnerable. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Natural predator may include birds of prey, civetsand snakes.

Dian’s Tarsier Characteristics

Dian’s tarsiers range in weight from 95 to 110 grams (3.35 to 3.9 ounces), with an average weight of 100 grams (3.5 ounces). They range in length from 11.5 to 12.1 centimeters (4.5 to 4.8inches), with their average length being 12 centimeters (4.7 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. [Source:Liubin Yang, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dian’s tarsiers are similar in size to spectral tarsiers. . Liubin Yang wrote in Animal Diversity Web: The coat color of Dian's tarsiers is grayish-buff and the tail is naked except for some hair at the end. Dian’s tarsier can be identified by the presence of short, white hairs flanking the upper lip and in the middle of the lower lip. It can be distinguished from Spectral tarsiers by the lack of brown fur at the hip, thigh, or knee and darker pigmentation on the tail, fingers, toes, and nails. Dian’s tarsier also has a more conspicuous black line of fur surrounding the eyes than does Spectral tarsiers. The ears of Dian’s tarsier are shorter and wider than those of Spectral tarsiers and there is a hairless patch at the base of each ear. The fur of subadults is slightly more gray and woolly than those of Spectral tarsiers. The digits are padded to allow gripping with grasping hands and feet. The finger nails of Dian’s tarsier are curved, pointed, and dark. Females have two pairs of mammary glands.

Because of a lack of tapetum lucidum,Dian’s tarsier eyes are enlarged to a diameter of approximately 16 millimeters. The eyes appear asymmetrical and not fully opened compared to those of Spectral tarsiers. Dian’s tarsier is able to rotate its head 180 degrees. The nasal region is covered with short hair except for an area of naked skin around the nostrils. Dian’s tarsier has well-developed, laterally folded nostrils. It also has large ears, but they are short compared to those of Spectral tarsiers. Dian’s tarsier has a more delicate mandible than that of Spectral tarsiers. The dental formula of this species is 2/1:1:3:3, and it has large, pointed upper and lower incisors. The upper canines are small.

Dian’s Tarsier Behavior, Communication and Reproduction

Dian’s tarsiers are arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (able to or good at climbing), saltatorial (adapted to leaping), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Unlike Spectral tarsiers, Dian’s Tarsier spends more time quadrupedally (using all four limbs for walking and running) and walking on horizontal supports. They do not exhibit torpor, a state of dormancy during food shortages. [Source: Liubin Yang, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The home range of Dian’s tarsiers, studied from radio-tracking, was described as smaller than that of Spectral tarsiers. The territory for one male was measured to be 0.8 hectares, and 0.5 hectares for three additional individuals. Studies in 2006 revealed the home ranges were 1.6 to 1.8 hectares. Female home ranges were as large as 1.8 hectares, which is smaller than the 2.3 to 3.1 hectares reported for Spectral tarsiers. Home ranges were smaller in slightly disturbed forests in which food and other resources, such as trees for locomotion and sleeping, were scarce.

According to Animal Diversity Web: This species has been described to live in groups of less than eight individuals composed of one adult male and one to three adult females and their offspring. They spend the day sleeping in a group-specific sleeping site, and at night they hunt and eat. Tremble observed that Dian’s tarsier sleeps in groups in locations with dense foliage, vine tangles, fallen logs, and tree cavities. Although they prefer to sleep in strangling figs, Dian's tarsiers can sleep in a variety of other sites. Sleeping sites were found at the periphery of home ranges, which implies territorial behavior in Dian’s tarsier to refresh their scent marks. At night, the breakdown of activities of Dian’s tarsier is as follows: 44 percent foraging, 28 percent traveling, 21 percent resting, and seven percent resting. Dian's tarsiers were observed to rest and move about randomly for most of the night after four hours of leaping. Before sunrise, adult and subadult tarsiers perform duets to strengthen group bonding and advertise their territories. Subsequently, triggered by the territorial (defend an area within the home range), duet songs, the tarsiers move across great distances as fast as 100 meters in 15 minutes to arrive at their sleeping sites.

Dian’s Tarsier Communication and Reproduction

Dian’s tarsiers sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. The also communicate with duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds) and scent marks produced by special epigastric glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. During the "male-female duet" females and males emit differently pitched sounds for 45 seconds at a sleeping site before dawn. There is regional variation in duet calls. The female begins calling by lowering the frequency pitch 16 to nine kHz, continues her call at seven or eight to one kHz, and concludes by bringing the pitch back up to nine to 16 kHz with a range of one to nine kHz. Similarly, the male's pitch falls from 10 kHz to five kHz at the beginning and steadily rises to 14 kHz until the end. It is thought that the duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds) serve to prevent conflict by warning potential intruders of the claimed territory and of already paired individuals. /=\

Although tarsiers were believed to be monogamous, studies have shown that Sulawesi tarsiers engage in facultative polygyny while forming strong pair bonds. Dian’s tarsiers engage in year-round breeding. Female tarsiers have been observed pregnant year round., with the average number of offspring being one. The mating behavior, reproduction and child rearing of Dian’s tarsier has not been studied. Studies on Spectral tarsiers have revealed that young tarsier females stay with their parents until adulthood, whereas young males leave as juveniles

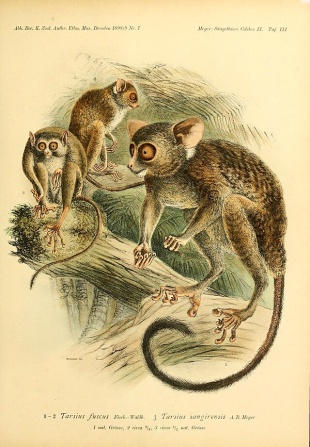

Tarsier species: 1) Western Tarsier (Cephalopachus bancanus), 2) Philippine Tarsier (Carlito syrichta), 3) Selayar Tarsier (Tarsius tarsier), 4) Makassar Tarsier (Tarsius fuscus), 5) Dian’s Tarsier (Tarsius dentatus), 6) Peleng Tarsier (Tarsius pelengensis), 7) Great Sangihe Tarsier (Tarsius sangirensis), 8) Siau Island Tarsier (Tarsius tumpara), 9) Sulawesi Mountain Tarsier (Tarsius pumalus), 10) Lariang Tarsier (Tarsius lariang), 11) Wallace’s Tarsier (Tarsius wallacei)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024