TARSIERS

Tarsiers (Tarsiidaetarsiers) are bizarre, lemur-like primates that look like squirrels from Mars on an LSD trip. About the size of al chipmunk and the same basic shape of an African bush and found only in the rainforests and jungles of Borneo, Indonesia and the Philippines, they have enormous eyes and a gremlin-like smile and can rotate their head nearly 360̊. They forage for food at night and are particularly fond of eating cockroaches Tarsiers are found only in some rainforest in some parts of the Philippines and Indonesia.

Tarsiers are named after their tarsal bones — two greatly elongated bones on their feet. These extra bones give tarsiers added leverage for jumping. Even though they are the size of rats they can leap 1.2 to 1.8 meters (four to six feet) in a single jump. The Dayaks of Borneo call tarsiers “hantu”, ancestral spirits. In the past, they were used as a totem animal of the head-hunting by Iban people of Borneo. Some scientist argue that they are prosimians like lemurs and lorises but others say they more closely related to monkeys and apes. Tarsiers are similar to lemurs but have different nose structures (a dry nose) and lack the reflective material behind the iris that lemurs have. Monkeys also share these traits. The olfactory and sight-related structures of tarsier skulls is similar to that of monkeys. Some scientist view them as missing links between lemurs and monkeys. The name tarsier refers to the tarsier’s elongated tarsal, or ankle, region.

Tarsiers have been compared with the creatures in the film "Grmelins" and are rumored to have been the inspiration for Yoda in Star Wars.Sharon Gursky-Doyen wrote in Natural History magazine, “Tarsiers stand out in numerous ways. Their saucerlike eyes are larger, relative to the head, than those of any other mammal. The animals boast two or three pairs of nipples, even though a female gives birth to only one infant at a time (apparently not all of the nipples are functional). And they are the most carnivorous of the primates, with a diet consisting entirely of insects and, in some cases, small vertebrates. They are extreme leapers — indeed, they are named for an unusually long tarsal (ankle) bone that acts as their launcher. They are reportedly capable of leaping as far as eighteen feet. [Source: Sharon Gursky-Doyen, Natural History magazine, October 2010]

There are 13 living species of tarsier, all in the genus Tarsius. Similar in size, morphology, and ecology, members of all tarsier species are all small, nocturnal (active at night), predatory primates known for their leaping and clinging abilities. They prefer secondary forests and mangroves with dense vegetation rather than canopied primary forests. The longest reported lifespan for a tarsier in captivity is over 17 years. The oldest individual caught in the wild was estimated to be 10 years old. Tarsiers change their behavior due to old age between 14 and 16 years of age. Signs of advanced aging may include graying of hair around the face and dental wear. For most tarsier species there are healthy numbers. The biggest threats to tarsiers are deforestation, habitat loss and capture by humans. [Source: Sabrina Archuleta, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TARSIER BEHAVIOR: SOCIALIZING, MOBBING AND MATING factsanddetails.com ;

TARSIERS OF INDONESIA AND BORNEO factsanddetails.com ;

SPECTRAL TARSIERS factsanddetails.com ;

PHILIPPINE TARSIERS factsanddetails.com l

PRIMATES: HISTORY, TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com ;

MONKEY TYPES: OLD AND NEW WORLD, LEAF- AND FRUIT-EATING factsanddetails.com ;

MAMMALS: HAIR, CHARACTERISTICS, WARM-BLOODEDNESS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Tarsier History

Tarsiers are the most "primitive" of the haplorrhine primates (suborder of primates that are characterized by their dry noses, forward-facing eyes, and larger brains than other primates). There are tarsier fossils dating to the Eocene Period (56 million to 33.9 million years ago). Tarsiers were once widely distributed, fossils of them have been found in America, Europe, North Africa, and Asia. The oldest fossil tarsiiform primate dates 50 million years ago and was found in sediments in China.[Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Four fossil species are known from five fossils: 1) an Eocene Period (56 million to 33.9 million years ago) from of Myanmar; 2) the the Middle Eocene Period (47.8 million to 38 million years ago) fossil from China; 3) a Middle Miocene Period (16 million to 11.6 million years ago) fossil from Thailand; 4) a Oligocene Period (33 million to 23.9 million years ago) fossil from Egypt; 5) a Miocene Period (23 million to 5.3 million years ago) fossil of Lybia.[Source: Sabrina Archuleta, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Sabrina Archuleta wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Because of the interest toward dividing the genus into three, some species are referred to as the attempted revised taxonomic names including the genera Carlito and Cephalopachus. Molecular data and physiological differences noted by Groves and Shekelle suggest this may be true. There may be some cryptic species of Tarsius yet to be discovered.

Tarsier Characteristics

Adults weigh between 80 and 165 grams and have a head and body length of 85 to 165 millimeters, with tail between 135 and 275 millimeters long. Their fur is usually gray or brown in color. The are built a little bit like a kangaroo in that they have short forelimbs and long hind legs and a long mostly naked tail. They also have relatively large hands and feet, long fingers and toes, rounded pads and highly developed first toes on their hands and feet allow them to grip almost any surface and effectively grasp prey. Tarsiers also have a muscular upper lip, which is associated with facial expressions.

Like all haplorrhines, tarsiers have hairs on their nose pads. There is little to no Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) although males may be slightly larger. For the most part both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. Like all mammals, they are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them) and homoiothermic (warm-blooded, having a constant body temperature, usually higher than the temperature of their surroundings).[Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Their fur is velvety or silky and buff, grayish brown, or dark brown on the back and grayish or buffy on the underside, generally resembling the color of dead leaves or bark. Species from higher altitudes sometimes have curly hair. Their most distinctive features are their round heads, remarkably large eyes that are directed forward, and their medium to large, hairless, and very mobile ears. Their eyes are so large that one of them weighs nearly as much as their brain. The skin in relatively naked areas of the body are often colored by glandular secretions. Males of some species have orange on the skin near their testicles and other species have dark brown spots on their ears. Their muzzle is short, and they seem to have almost no neck (although they are capable of turning their head over 180 degrees!). Tarsiers have long, slender bodies, but tend to look round because of their habit of crouching while clinging to a branch.

The skulls of tarsiers are unmistakeable due to the huge, forward-directed orbits. These have expanded rims and are separated by a thin interorbital septum. The dental formula is 2/1, 1/1, 3/3, 3/3 = 34. The upper medial incisors are large and pointed; the upper canines are small; and the upper molars are tritubercular. /=\

Tarsier Limbs

According to Animal Diversity Web: Members of the genus Tarsius possess long, slender hands, feet, and digits. Their hands are thought to be the longest of any living primate relative to body size. These extremely elongated hands are designed for clinging and gripping despite the lack of opposable thumbs. [Source: Kenzie Mogk, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tarsier forelimbs are short and their hindlimbs elongated, the hindlimbs are longer in proportion to body length than in any other mammal. They are unique among mammals in that the elongation of their hindlimbs is the result of lengthening of the tarsals (especially the calcaneum and navicular) rather than the metatarsals. By elongating the tarsals, tarsiers can lengthen the limbs without sacrificing dexterity of the hands, often a result of metatarsal elongation. The elongation of their tarsals gives their names "Tarsiidae" or "Tarsius". The digits are extraordinarily long and tipped with soft, rounded toe pads that help them grip and cling to surfaces. /=\

While the thumb is not opposable, but the big toe is. All digits have flattened nails except the second and third hind toes, which have claw-like nails used for grooming (sometimes called "toilet claws"). The tail is naked except for tufts of hairs at the tip and is thin and long, from 20 to 25 centimeters. Tarsier species have ridges of skin on the ventral surfaces of their tail that help them to stabilize themselves against tree trunks when clinging. /=\

Tarsiers and Trees

Tarsier species are are found primarily in tropical, forested habitats with dense vertical growth. They use their leaping and clinging abilities to move around via vertical tree trunks or other vertical supports, which are important components of their habitats. They may venture into non-forested habitats if vertical surfaces for clinging and leaping are available. They can jump to the ground to move around but are vulnerable there and only stay on the ground for short periods. Sleeping roosts in trees — typically hollows, and clusters of vines are also important components of their habitats. Most of their foraging time is spent below one meter in the vertical structure of a forest. Sleeping roosts are mainly at two to five meters above the ground. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tarsiers are quite mobile in the trees. When they are awake their eaas are in nearly constant motion. Their disproportionally long legs and elongated tarsal bones give them great leaping ability. They can make quick, acrobatic leaps of up to six meters (20 feet) — more than 20 times their body length — with great ease. Their leaps have been compared to those of a tree frog because they can leap and land on near flat surfaces.

Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web Tarsiers are extremely specialized for vertical clinging and leaping. Their rigid tails with ventral ridges help them to cling to vertical supports. Their extremely elongated hindlimbs, well-developed leg muscles (thigh muscles may represent 12 percent of total body mass), and long fingers with gripping tips enable them to make impressive leaps of up to 45 times their body length. They are especially adept at backward leaping, propelling themselves backwards, rotating in the air, and landing with their feet. They also use quadrupedal (use all four limbs for walking and running) locomotion, small hops, and can run on their hindlimbs on the ground.

Tarsier Senses

Tarsiers sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with sound and chemicals usually detected by smell. They leave scent marks produced by urine and special glands and placed objects in their environment so others can smell and taste them. Tarsiers use scent marking and vocalizations to mark and defend territories and to confirm group membership. Their scent glands are on their lips, chest, and anogenital region. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tarsiers have acute hearing and night vision. The tarsier’s ability to rotate it head like an owl, almost 360 degrees, gives them an extraordinary field of vision. Headhunters in Borneo viewed the tarsier’s head turning ability as an omen. A tarsier turning it head 360̊ was viewed a sign that a head was going to be lost soon. A tarsier’s sense of smell is not developed in part because it eyes take up so much space in its head there isn’t any room left for a sophisticated nose. Consequently smell is not a very important sense and is sued mainly to mark territory.

David Attenborough wrote, “Uniquely among prosimians, the retina at the back of the eye has a groove down the middle which gives extra definition to its sight. Its neck is so mobile it can be twisted through 180 degrees in either direction. When the animal’s ears pick up the sound of an insect moving behind it, its head swivels round immediately and its sight is so good and its reactions so swift that it can pluck a fast-flying insect from the air with the skill of a cricketer making a difficult catch in the slips.”

“The tarsier’s nostrils, which project sideways, are circular. Fur grows almost to the edge of them and surrounds them, separating them from the upper lip. The nostrils of other prosimians, in contrast, are shaped like commas, permanently moist and linked to the upper lip by a strip of naked skin. The difference in the structure of the nose is a reflection of the smallest extent to which the tarsier relies on its sense of smell compared with other prosimians. The only other clambering tree-dwellers that have noses like the tarsier are the monkeys. Those scientists concerned with working out the ancient lineages of animals regard this as being of great significance. The tarsier, they believe, is the only prosimian that truly deserves the title, It, unlike the others, really is a “pre-monkey”, an ancient twig on the great branch that was to lead to that group. It was also, of course, the branch that lead to ourselves.”

Tarsier Hearing and Vision

Tarsiers have the biggest eyes of any mammal relative to their body weight. According to Animal Diversity Web: Their large, close-set eyes are 150 times larger in relation to their body than human eyes and, relative to body size, are largest eyes of any animal in the world. Each eye is larger than its brain and both eyes together are larger than its stomach. If human eyes were as big in proportion to their bodies they would be the size of softballs. Their eyes are so big the tarsiers can’t rotate them in their sockets, which is why tarsiers have developed their ability to rotate their heads.

Interestingly, tarsiers lack a tapetum lucidum, a highly reflective layer behind the retina that is characteristic of most nocturnal (active at night), mammals. Instead tarsiers have extremely large eyes and a well-developed fovea to maximize light-gathering capacity and to allow the development of highly resolved pin-sharp vision. These adaptations have bestowed tarsiers with the most acute night vision of all primates. [Source: Kenzie Mogk, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tarsiers have excellent hearing. Their ears are very thin, mobile and somewhat similar to those of bats. They can be unfurled and retracted as needed; twisted and crinkled to focus sound; and can easily pick of the sounds of moving insects. When a tarsier hears a beetle it swivels it head and the ears bend forwards to get a better read on the sound.

Tarsiers have huge eyes but rely on their ears The most acoustically sensitive acute primate, Philippine tarsiers hear sounds up to 91 kiloherz — a level inaudible to nearly all terrestrial mammals. Such senses may help the animalss catch insects and escape predators. In comparison humans can only hear sound up to 20 kilohertz.

Tarsier Food and Hunting

Horsefield tarsius

Tarsiers are the only primates that are totally carnivorous. They insectivores (mainly eat insects) but also eat non-insect arthropods and small mammals and reptiles. They use their exceptional hearing and night night to locate prey and then pounce on it with rapid leaps and quick grabs. They can feed on prey up to their own size, including small lizards, frogs, crabs, nesting birds, bats and even snakes but prefer arthropods, especially moths and butterflies, cicadas, orthopterans (grasshoppers and crickets), ants, and beetles. Other primates eat mostly fruits and leaves. Tarsiers capture methods include quickly grabbing prey with their strong, long fingers or leaping onto prey.

Tarsiers hunt by leaping from tree trunks and pouncing on prey, often on the ground. They kill prey by biting down with the anterior teeth, and they chew with a side to side motion. Tarsiers typically take large prey for their body size and consume the entire prey, which can result in large fluctuations in body weight. When a tarsier sees prey it adjust its position and suddenly In captivity, tarsiers capture prey by carefully watching prey movements and leaping forward suddenly to capture prey in both hands. leaps. Lorises and tarsiers are the only primates that eat mostly animal prey.

Tarsiers chew their food with a side-to-side motion of the jaw while the tarsier sits on its hind limbs grasping a tree branch. Tarsiers also ingest water by lapping, or take in liquid using the tongue. Most tarsier species forage at less than 1.5 meters from the ground. Around 60 percent of prey is caught on branches or leaves and around 25 percent is caught in the air. Only about five percent of prey are caught on the ground. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tarsier Predators and Human Threats

Tarsiers are preyed upon by a any number of arboreal predators that are active at night like tarsiers and share their tropical, forested habitats. They have been observed mobbing and being captured by snakes and slow lorises. Their nocturnal habits, keen vision and hearing, quickness hleps them elude predation. Their habit of clinging to vertical surfaces is also an obstacle that makes it difficult to capture them.

The main predators of tarsiers are monitor lizards, civets, snakes, and birds of prey. In the presence of bird predators, individuals vocalize and disperse to hide. When in the presence of a terrestrial predator, such as a snake, individuals “mob” the threat. When mobbing, all individuals respond to a threat with vocalizations as each repeats lunging towards and retreating from the predator. Recent studies suggest predation by domestic animals as habitats grow smaller, and people who capture and sell or who erroneously consider them pests in farmland./=\

Spectral tarsiers have been a popular tourist attraction in Tangkoko, northern Sulawewsi. Philippine tarsiers are a popular tourist attraction on the island of Bohol in the Philippines. Tarsiers are generally too small to be hunted by humans for food and not kept as pets but often don't mind humans observing them in the wild.

As of the late 2000s, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List recognized eight species, including the Lariang tarsier (Tarsius lariang, 2006), of which two species are considered endangered, three were considered vulnerable, one was near threatened, and two were data deficient. All tarsier species are considered threatened by habitat destruction of 30 percent or more throughout their range. They do better in primary forest habitats than degraded habitat. They may be negatively impacted by human use of insecticides in some areas. Taxonomic uncertainty makes assessing risks and coming up with conservation plans difficult.

Tarsius Classification and Genera

Tarsiers occupy a unique primate niche and have many morphological and behavioral specializations. The evolutionary history and position of living tarsiers within the order primates has been debated for decades. The animals have alternately been classified with strepsirrhine and Prosimii primates (lemurs, galagos ("bushbabies") and pottos from Africa, and lorises from southern Asia) or as the sister group to the simians (monkeys and apes) in the infraorder Haplorhini. Recently In tarsiers have been rmoved from the suborder Prosimii to the suborder Haplorrhinii, although their classification is still under debate.

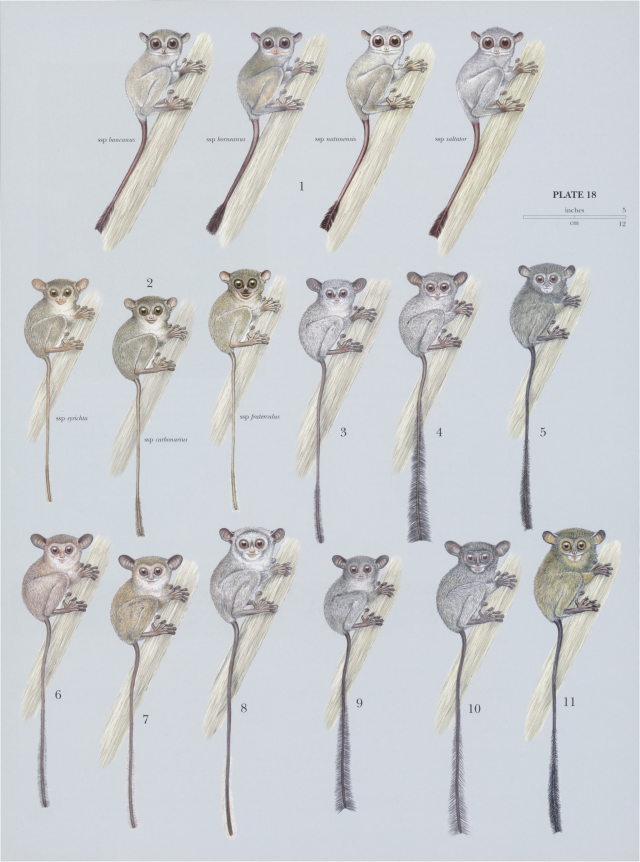

For a long time all living tarsier species were classified in the genus Tarsius. In 2010, Colin Groves and Myron Shekelle suggested splitting the genus Tarsius into three genera: the Philippine tarsiers (genus Carlito), the western tarsiers (genus Cephalopachus), and the eastern tarsiers (genus Tarsius). This was based on differences in dentition, eye size, limb and hand length, tail tufts, tail sitting pads, the number of mammae, chromosome count, socioecology, vocalizations, and distribution. Genus Cephalopachus (Horsfield's tarsier, Cephalopachus bancanus); 1) C. b. bancanus, 2) C. b. natunensis, 3) C. b. boreanus, 4) C. b. saltator.[Source: Wikipedia]

The genus Tarsius consists of 12 tarsier species including: Dian’s tarsier (T. dentatus), Makassar tarsier (T. fuscus), Lariang tarsier (T. lariang), Peleng tarsier (T. pelengensis), pygmy tarsier (T. pumilus), Sangihe tarsier (T. sangirensis), Jatna’s tarsier (T. supriatnai), spectral tarsiers (T. tarsier), Siau Island tarsier (T. tumpara), and (Wallace’s tarsiers). [Source: Sabrina Archuleta, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Genus Carlito (Philippine tarsier, Carlito syrichta) contains 1) C. s. syrichta, 2) C. s. fraterculus (to be combined into C. s. syrichta?) and 3) C. s. carbonarius. In 2014, scientists published the results of a genetic study from across the range of the Philippine tarsier, revealing previously unrecognised genetic diversity. Three subspecies are recognised in the established taxonomy: Carlito syrichta syrichta from Leyte and Samar, C. syrichta fraterculus from Bohol, and C. syrichta carbonarius from Mindanao. Their analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences suggested that ssp. syrichta and fraterculus may represent a single lineage, whereas ssp. carbonarius may represent two lineages – one occupies the majority of Mindanao while the other is in northeastern Mindanao and the nearby Dinagat Island,

Difficulty Classifying Tarsiers

Phillippine tarsier

Sharon Gursky-Doyen wrote in Natural History magazine, “The eighteenth-century French naturalist Buffon, who, upon examining a juvenile tarsier, thought it might be a kind of opossum, was not the first to find them a bundle of contradictions. While other living primates fall fairly neatly into two main groups — the Strepsirrhini (the suborder that embraces lemurs, lorises, and galagos) and the Haplorrhini (the one that includes monkeys, apes, and humans) — tarsiers seem to belong to both at once. [Source: Sharon Gursky-Doyen, Natural History magazine, October 2010]

“A variety of characteristics mark tarsiers as Strepsirrhini: their small body size, grooming claws, nocturnal habits, and two-horned (as opposed to single-chambered) uterus, as well as aspects of their parental care (a mother will park her infant in a tree while she forages, and infants are transported by mouth, the way a dog carries a puppy). On the other hand, tarsiers possess numerous features linking them with the Haplorrhini, including a dry nose, a mobile upper lip that is not attached to the nose, a fovea centralis (a depression in the middle of the retina that increases visual acuity), and a hemochorial placenta, which provides close contact between the mother's blood and the fetal circulatory system. Certain skeletal traits, most notably an eye socket backed by bone, also seem to favor a haplorrhine connection, but they may have evolved independently.

“Most taxonomists today assign tarsiers to their own infraorder within the suborder Haplorrhini, but their unusual combination of traits shows that their lineage branched off long ago from the rest of the suborder. Fos- sils representing Tarsius and closely related genera, found in North America, Africa, and Asia, date as far back as 45 million years, and their lineage is believed to have separated from all the other Haplorrhini as early as 71 million years ago. Strepsirrhini and Haplorrhini diverged perhaps 78 million years ago, not long after the origin of all primates. Consequently, modern tarsiers are pivotal in understanding the roots of primate evolution.

Tarsier Species

The number of tarsier species is debated, but most biologists recognize at least 13 species: One is found on several islands of the Philippines. Another is found in southern Sumatra and Borneo and some nearby islands. Sulawesi is one of the best places to see them. Several species are found there. For most species there are healthy numbers.

The western tarsier lives in primary and secondary forests of hilly lowlands and swampy plains in Borneo and southern Sumatra. It weighs 86 to 135 grams (3 to 4.8 ounces) and measures 12.1 to 15.4 centimeters (4.8 to 6.1 inches) from head to foot. Its tail is 18.1 to 22.4 centimeters (7.1 to 8.8 inches). Its numbers are unknown. Its habitat is threatened by logging and palm oil plantations. [Source: Canon advertisement in November 2011 National Geographic]

The western tarsier has huge eyeballs and is nocturnal. A single eyeball is larger than its brain. A determined hunter, it consumes one-tenth of its body weight each night and uses sound to locate prey such as insects, spiders and other arachnids and small animals. It captures many kinds of prey by leaping on them and is capable of covering 40 times its body length in a single pounce. It can also turn its head 180 degrees like an owl.

Horsfeld's tarsier, Dian’s tarsier, and Spectral tarsiers are considered vulnerable. Philippine tarsiers are considered near threatened. Pelengensis tarsier and Sangihe tarsiers are considered Endangered. Siau Island tarsiers are critically endangered and were listed as one of the world's 25 most endangered primates by the IUCN Species Survival Commission.Tarsius lariang, Pygmy tarsiers, and Wallace’s tarsiers are listed as data deficient. Spectral tarsierss are protected through international treaties. /=\

Studying Tarsiers

Tarsier Expert: Sharon Gursky-Doyen is an associate professor of anthropology at Texas A&M University. She received her PhD from the State University of New York at Stony Brook and has been studying tarsiers throughout Sulawesi, Indonesia, since 1990. While continuing her work on spectral tarsiers, she is also investigating the effects of altitude on the recently rediscovered pygmy tarsier. She is the author of The Spectral Tarsier f(Prentice Hall, 2007) and coeditor (with K.A.I. Nekaris) o{ Primate Aiiti-Piedator Strategics (Springer, 2007).

Sharon Gursky-Doyen wrote in Natural History magazine, “Tarsiers remain shrouded in mystery, because studying their behavior is no easy feat. Not only are they small nocturnal forest-dwellers (bad enough!), but, as I learned early on, some of their most peculiar features make them hard to track. Then, tarsiers have the owl-like ability — shared with no other mammal — to rotate their heads backward 180 degrees. Often when I am out in the jungle tracking a tarsier, it will look in one direc- tion, but then leap the opposite way! That makes it very easy to lose the individual I am following. And unlike the majority of nocturnal mammals — but like all haplorrhines — tarsiers lack the light-reflecting layer of tissue behind the retina known as the tapctum lueiihitii. In low light, that "bright carpet" improves vision and, as a byproduct, renders an animal's pupils visible as "eyeshine." Absent any eyeshine, the strik- ingly large eyes of tarsiers do not broadcast their location as one might hope. [Source: Sharon Gursky-Doyen, Natural History magazine, October 2010]

“When I first began studying tarsiers in the 1990s, they were considered solitary creatures, like most other nocturnal foragers. But when I started tracking them using radio telemetry, I learned that sometimes other tarsiers w^ere not so far away. The conventional approach is to put a radio collar on an individual and track it over the course of one night, picking different nights to watch different individuals. To determine whether tarsiers might be more social than they were reputed to be, I tried a new technique. I would radio-collar a pair of tarsiers and perform "simultaneous focal follows" with an assistant: the two of us would synchronize our watches, each take a radio receiver, and then note our respective tarsier's location every five minutes over the course of twelve hours. So, for example, I might observe a mother while my assistant would simultaneously track her offspring; or we might track two mates this way. Then we would compare our notes. Once we started watching pairs rather than individuals, we , discovered that spectral tarsiers are far from solitary. “To record insect distribution on the ground and in the air, I began collecting insects by means of pittall traps (holes in the ground), sweep nets (similar to butterfly nets), and Malaise traps (stationary nets named for the Swedish entomologist Rene Malaise).

New Tarsier Species

In May 2017, scientists announced the discovery of two new species of tarsier on the northern peninsula of Sulawesi in an article published in the journal Primate Conservation. These new members of the tarsier family upped the total of tarsier species on Sulawesi and nearby islands to 11. Mike Gaworecki of mongabey.com wrote: “The species were given the names Tarsius spectrumgurskyae and Tarsius supriatnai in honor of two scientists who have played central roles in conservation efforts in Indonesia. Dr. Sharon Gursky, a professor of anthropology at Texas A&M University, has studied her namesake species in Sulawesi’s Tangkoko National Park for a quarter century and is widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost experts on tarsier behavior. And Dr. Jatna Supriatna, a professor of biology at the University of Indonesia, has sponsored much conservation science research in Indonesia and served as director of Conservation International’s operations in the country for 15 years. [Source:Mike Gaworecki, mongabey.com, May 2017]

Tarsier species: 1) Western Tarsier (Cephalopachus bancanus), 2) Philippine Tarsier (Carlito syrichta), 3) Selayar Tarsier (Tarsius tarsier), 4) Makassar Tarsier (Tarsius fuscus), 5) Dian’s Tarsier (Tarsius dentatus), 6) Peleng Tarsier (Tarsius pelengensis), 7) Great Sangihe Tarsier (Tarsius sangirensis), 8) Siau Island Tarsier (Tarsius tumpara), 9) Sulawesi Mountain Tarsier (Tarsius pumalus), 10) Lariang Tarsier (Tarsius lariang), 11) Wallace’s Tarsier (Tarsius wallacei)

“As recently as the 1990s, there were believed to be just one or two species of tarsiers in the forests of Sulawesi. Myron Shekelle, a professor of anthropology at Western Washington University and the lead author of the paper describing the two new species to science, has spent the past 23 years helping to show that tarsiers actually represent a cluster of as many as 16 or more species. He led a team of researchers who used the species’ vocalizations and genetic data to establish T. spectrumgurskyae and T. supriatnai as distinct from other tarsiers. “As with many nocturnal species, they look quite similar,” Shekelle told Mongabay, explaining why tarsier taxonomy was ripe for revision when he first began his work. “So visually-oriented diurnal human taxonomists ‘look’ for differences among species and don’t ‘see’ them. Thus, studies of museum specimens, which were conducted by competent and highly qualified taxonomists, tended not to pick up the differences.”

“Field biologists first began to notice differences in the bioacoustics of populations of nocturnal organisms like frogs, crickets, and grasshoppers in the 1950s, Shekelle says. “This led to the theory that these populations were actually a cluster of related ‘cryptic’ species. That is to say, they were taxonomically cryptic, meaning that taxonomists had overlooked the true diversity among many (mostly nocturnal) animals.” In other words, nocturnal creatures may not typically look that much different from their closest relatives, but they often sound different. And new technologies, first deployed in the early 1990s, have allowed us to test the predictions made by scientists back in the 1950s based on their observations of bioacoustics by collecting and comparing genetic data from populations of wild animals. “Painting with a broad brush, the genetic evidence typically provides robust support for these hypotheses, and in many cases show the splits between the cryptic species to be far deeper than had been imagined,” Shekelle said. “For example, with T. spectrumgurskyae and T. supriatnai, genetic evidence indicates a split of 300,000 years.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024