GRAY LANGURS OF SOUTH ASIA

Semnopithecus is a genus of Old World monkeys native to the Indian subcontinent, with all species except for two being commonly known as gray langurs. Members of this genus tend to spend as much time on the ground as in the trees and inhabit forest, lightly wooded habitats, and urban areas. Mostly walk quadrupedally (on all fours) and make occasional bipedal hops, climbing and descending supports with the body upright, and leaps. Langurs can leap 3.6–4.7 meters (12 to 15 feet) horizontally and 10.7–12.2 meters (35–40 feet) in a descending direction. Most species are found at low to moderate altitudes, with the exception of the Nepal gray langur and Kashmir gray langur which can be found up to 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) in the Himalayas. [Source: Wikipedia]

Gray langurs are largely gray but some are more yellowish, with a black face and ears. As a rule, species can be differentiated by the darkness of their hands and feet, their overall color and the presence or absence of a crest. Generally, northern Indian gray langurs have their tail tips looping towards their head during a casual walk whereas southers Indian and Sri Lankan gray langurs have an inverted "U" shape or a "S" tail carriage pattern. There are also significant variations in the size depending on the sex, with the male always larger than the female. The head-and-body length ranges from 51 to 79 centimeters (20 to 31 inches), with tails, ranging from 69 to 102 centimeters (27 to 40 inches) and always longer than their bodies. Langurs from the southern part of their range are smaller than those from the north. The average weight of gray langurs is 18 kilograms (40 pounds) in the males and 11 kilograms (24 pounds) in the females. The larger gray langurs among the largest species of monkey found in Asia.

Gray langurs are diurnal. They sleep during the night in trees but also on man-made structures like towers and electric poles when in human settlements.When resting in trees, they generally prefer the highest branches. Gray langurs are primarily herbivores. However, unlike some other colobines they do not depend on leaves and leaf buds, but also eat coniferous needles and cones, fruits and fruit buds, shoots, roots, seeds, grass, bamboo, fern rhizomes, mosses, and lichens. Leaves of trees and shrubs are their most preferred food, followed by herbs and grasses. Non-plant material consumed include spider webs, termite mounds and insect larvae. They forage on agricultural crops and other human foods, and even handouts. Although they occasionally drink, langurs get most of their water from the moisture in their food.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LANGURS: TYPES, GENUSES, LEAF MONKEYS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

HANUMAN LANGURS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR. HUMAN factsanddetails.com

LANGURS AND LEAF MONKEYS OF SOUTHEAST ASIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com;

DOUC LANGURS (DOUCS): SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

LANGURS OF INDONESIA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

LANGURS AND LEAF MONKEYS OF NORTHERN INDONESIA, BORNEO AND MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

PRIMATES: HISTORY, TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com ;

MONKEY TYPES: OLD AND NEW WORLD, LEAF- AND FRUIT-EATING factsanddetails.com ;

MAMMALS: HAIR, CHARACTERISTICS, WARM-BLOODEDNESS factsanddetails.com

Gray Langur Behavior

Gray langurs exist in three types of groups: 1) one-male groups, comprising one adult male, several females and offspring; 2) multiple-male groups, comprising males and females of all ages; and 3) all-male groups. All-male groups tend to be the smallest of the groups and can consist of adults, subadults, and juveniles. Some populations have only multiple-male groups as mixed sex groups, while others have only one-male groups as mixed sexed groups. Some evidence suggests multiple-male groups are temporary and exist only after a takeover, and subsequently split into one-male and all-male groups. [Source: Wikipedia]

Social hierarchies can be found in all group types. In all-male groups, dominance is attained through aggression and mating success. With sexually mature females, rank is based on physical condition and age. The younger the female, the higher the rank. Dominance rituals are most common among high-ranking langurs. Females within a group are matrilineally related. Female memberships are also stable, but less so in larger groups. Relationships between the females tend to be friendly. They will do various activities with each together, such as foraging, traveling and resting. They will also groom each other regardless of their rank. However, higher-ranking females give out and receive grooming the most

In one-male groups, the resident male is usually the sole breeder of the females and sires all the young. In multiple-male groups, the highest-ranking male fathers most of the offspring, followed by the next-ranking males and even outside males will father young. Higher-ranking females are more reproductively successful than lower-ranking ones. Female gray langurs do not make it obvious that they are in estrous. However, males are still somehow able to deduce the reproduction state of females. The gestation period of gray langur lasts around 200 days. A single offspring is usually born. Infanticide is common among gray langurs.

Gray langurs make a number of vocalizations. The include: 1) loud calls or whoops made only by adult males during displays; 2) harsh barks made by adult and subadult males when surprised by a predator; 3) cough barks made by adults and subadults during group movements; 4) grunt barks made mostly by adult males during group movements and agonistic interactions; 5) rumble screams made in agonistic interactions; 6) pant barks made with loud calls when groups are interacting; 7) grunts made in many different situations, usually in agonistic ones; 8) honks made by adult males when groups are interacting; 9) rumbles made during approaches, embraces, and mounts; 10) hiccups made by most members of a group when they find another group.

Gray Langur Species

Nepal Gray Langurs (Semnopithecus schistaceus, Hodgson, 1840) are gray in color. They live in the Himalayas. They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. At 26.5 kilograms (58 pounds), the heaviest langur ever recorded was a male Nepal gray langur. They live in the forest, shrubland, and eat leaves and fruit, as well as seeds, roots, flowers, bark, twigs, coniferous cones, moss, lichens, ferns, shoots, rhizomes, grass, and invertebrate animals. They are a species of least concern. Their numbers are unknown. Their population is declining.

Tarai Gray Langurs (Semnopithecus hector, Pocock, 1928) are gray in color. They live in the Himalayas. They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest and eat leaves, fruit, and flowers. They are a near-threatened species. Their numbers are unknown. Their population is declining.

Tufted Gray Langurs (Semnopithecus priam, Blyth, 1844) are brown in color. There are three subspecies: 1) S. P. anchises; 2) S. P. priam; and 3) S. P. thersites. They live in Southern India and Sri Lanka. They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest and shrubland and eat leaves and fruit. They are a near-threatened species. Their numbers are unknown. Their population is declining.

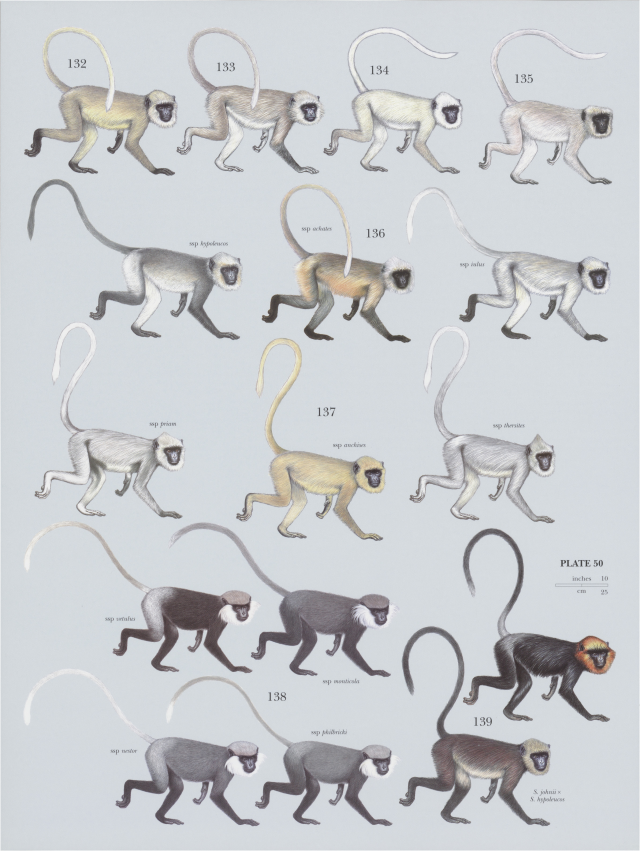

Langur species: 132) Bengal Sacred Langur (Semnopithecus entellus), 133) Chamba Sacred Langur (Semnopithecus ajax), 134) Terai Sacred Langur (Semnopithecus hector), 135) Nepal Sacred Langur (Semnopithecus schistaceus), 136) Malabar Sacred Langur (Semnopithecus hypoleucos), 137) Tufted Gray Langur (Semnopithecus priam), 139) Nilgiri Langur (Semnopithecus john)

Purple-Faced Langurs (Semnopithecus vetulus, Erxleben, 1777) are gray in color. There are four subspecies: 1) T. v. monticola (Montane purple-faced langur); 2) T. v. nestor (Western purple-faced langur); 3) T. v. philbricki (Dryzone purple-faced langur); and 4) T. v. vetulus (Southern lowland wetzone purple-faced langur). They live in Sri Lanka. They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest and eat leaves, fruit, flowers, and seeds. They are endangered. Their numbers are unknown.

Langurs and Leaf Monkeys in India

Black-Footed Gray Langurs (Semnopithecus hypoleucos, Blyth, 1841) are gray in color. There are three subspecies: 1) S. h. achates; 2) S. h. hypoleucos; and 3) S. h. iulus. They live in Southern India. They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest and shrubland and eat leaves, fruit, and flowers. They are a species of least concern. Their numbers are unknown. Their population is declining.

Kashmir Gray Langurs (Semnopithecus ajax, Pocock, 1928) live in the Himalayas. They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest and eat leaves, bark, and seeds. They are endangered. There are only 1,400–1,500 of them. Their population is declining.

Nilgiri Langurs (Semnopithecus johnii, J. Fischer, 1829) are gray in color. They live in India . They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest and eat leaves, fruit, and flowers. They are vulnerable. There are 9,500–10,000 of them. Their population is steady.

Northern Plains Gray Langurs (Semnopithecus entellus, Dufresne, 1797) are gray in color. They live in India. They are 41–78 centimeters (16–31 inches) long, with a 69–108 centimeter (27–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest, savanna, and shrubland and eat leaves, fruit, and flowers, as well as insects, bark, gum, and soil. They are a species of least concern.Their numbers are unknown. Their population is declining.

Langurs and Leaf Monkeys in South Asia

François' Langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi, Pousargues, 1898) are gray monkeys. They live in South Asia. They are 40–76 centimeters (16–30 inches) long, with a 57–110 centimeter (22–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest, rocky areas, and caves and eat leaves, fruit, and seeds, as well as insects. They are endangered. There are only 2,000–2,100 of them. Their population is declining.

Gee's Golden Langurs (Trachypithecus geei, Khajuria, 1956) are brown in color. They live in South Asia. They are 50–75 centimeters (20–30 inches) long, with a 70–100 centimeter (28–39 inch) tail. They live in the forest and eat Fruit, leaves, flowers, seeds, and twigs. They are endangered. There are only 6,000–6,500 of them. Their population is declining.

Shortridge's Langurs (Trachypithecus shortridgei, Wroughton, 1915) are gray in color. They live in South Asia. They are 40–76 centimeters (16–30 inches) long, with a 57–110 centimeter (22–43 inch) tail. They live in the forest and eat leaves, flowers, and fruit. They are endangered. Their numbers are unknown. Their population is declining.

Nilgiri Langurs

Nilgiri langur (Trachypithecus johnii) are also known as black leaf monkeys, hooded leaf monkeys, Indian hooded leaf monkeys, John's langur, Nilgiri black langurs and Nilgiri leaf monkey. There is some debate over the classification of this species, with some taxonomists placing it with Hanuman langurs, while others consider it a species of Trachypithecus. Still others place them in their own genus known as Kasi. Nilgiri langurs are therefore named Trachypithecus johnii, Semnopithecus johnii, Presbytis johnii, and Kasi johnii in various scientific literature.[Source: Claire Solomon, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

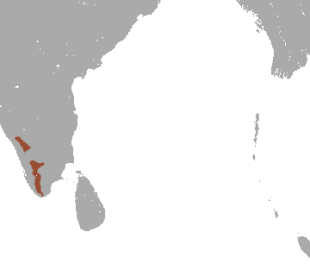

Nilgiri langur are endemic to the southern portions of the Western Ghats, a mountain range in the south of India. They inhabit a wide range of forest habitats: primarily in secondary moist deciduous forests and wet evergreen but also semi evergreen forests. They prefer locations that are as close to water, and as far away from humans as possible. They have lived in captivity up to 29 years.

Nilgiri langurs sleep in middle or lower canopy trees of medium height. They reside in the sholas of the Western Ghats. Sholas are narrow stretches of forest surrounded by grasslands, nestled in valleys at high elevations. Nilgiri langurs live at elevations between around 300 and 2,500 meters (984.25 to 8,200 feet) and are most commonly found at approximately 1,400 meters (4,593).

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Nilgiri langurs are listed as Vulnerable. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Nilgiri langurs are poached for their body parts, which are sold for use in traditional medicine and aphrodisiacs, and for their skins, which are used as drum heads. Nilgiri langurs are also captured and sold as pets. Nilgiri langurs are known as crop pests to cauliflower, potato, cardamom, and garden poppy farmers but many place blame on humans for encroaching on the natural habitat of Nilgiri langurs.

Only 50 percent of the Nilgiri langurs’ territory is within the protected area in the Western Ghats. Their population is estimated at around 10,000. Their main threats are habitat destruction and poaching. for various purposes. There is correlation between human disturbance, instances of infanticide among langurs, which is more likely when females leave their young unattended as the struggle to find food. Natural predators include the Indian wild dog.

Nilgiri Langur Characteristics and Feeding

Nilgiri langurs range in weight from 9.1 to 14.8 kilograms (20 to 32.6 pounds) and range in length from 58 to 80 centimeters (22.8 to 31.5 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Sexes are colored or patterned differently. The body and head of males ranges between 78 and 80 centimeters; for females the range is 58 to 60 centimeters,. Males weigh between 9.1 and 14.8 kilograms while females weigh between 10.9 and 12 kilograms. The tails of both males and females vary in length between 68.5 and 96.5 centimeters. [Source: Claire Solomon, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Nilgiri langurs are colobine monkeys, which share characteristic such as a complex stomach, a reduced thumb, and a long tail. Nilgiri langurs have a shiny black coat with a reddish-brown to gold head. Newborns are reddish-brown for up to ten weeks, when they gain the hue of the adults. Similar to purple faced langurs, Nilgiri langurs have dark faces and white sideburns. Females have white patches on their thighs that distinguish them from males. /=\

Nilgiri langurs are primarily folivores (eat mainly leaves) but are also considered herbivores (eat plants or plants parts), frugivores (eat fruits), granivore (eat seeds and grain), lignivore (eats wood). Animal foods include insects. Among the plant foods they eat are bark, stems, nuts, flowers. They also eat detritus and soil but leaves make up the majority of their diet. They prefer the large leaves of teak trees, Tectona grandis. These langurs reportedly choose foods based on digestibility; they have a diet that is low in both fiber and vegetable tannin. It is hypothesized that they use the soil they consume as an antacid, which stabilizes the pH level of the stomach.

Nilgiri langurs spend almost half of their waking hours feeding. They consume over 115 different species, including at least 58 tree species, six shrubs, 13 non-woody plants, 32 vines, and six parasitic plants. When eating leaves, these langurs eat the tips first, then they rip off the sides to expose the midrib, which they also consume. This is a delicate and deliberate process, with one side of each leaf pealed back at a time to expose the midrib of the leaf. Each leaf takes approximately 30 seconds to eat. During eating periods, in which Nilgiri langurs take and consume leaves almost continuously, about 5-10 seconds are taken between leaves. /=\

Nilgiri Langur Behavior and Communication

Nilgiri langur are arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (able to or good at climbing), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), territorial (defend an area within the home range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). During peak activity, these monkey engages alternatively in feeding and resting. Their average territory size is 10,000 square meters. The size of the home range fluctuates with quality of habitat during the seasons: when preferred food is readily available, the range is smaller; when it is more scarce, the home range increases. The core area of this species includes feeding sites and resting or sleeping sites. These sites are chosen as close to water and as far away from humans as possible. [Source:Claire Solomon, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Claire Solomon wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Nilgiri langurs generally live in small female-centric groups. These groups can consist of one male and several females, several males and several females, or one or more solitary males. Typically, the uni-male, multi-female model is the most common. Group sizes have been documented between one and 27 members, with an average of 14 or 15 individuals. Social activities that are visible, primarily during resting periods. Examples of these are grooming, playing, chasing, watching, fighting, mounting, aggression, and dominance assertion.

Nilgiri langur exhibits subtle dominance hierarchies. There are two dominance structures within each group, one for males and one for females. Dominance structures are not completely rigid, in that dominance is expressed in the number of times a specific individual is forced to act subordinately to another. For example, an alpha female with higher status may act dominantly towards a beta female the large majority of the time, but would behave subordinately on rare occasions. However, a gamma female would usually behave subordinately towards a beta female, expressing dominance very infrequently. /=\

Social status is more important for males than for females. The alpha female displays dominance mainly in choosing preferred feeding and sleeping sites. The alpha male displays dominance most noticeably in determining the traveling direction and timing of the entire group, but also in freedom of choice over daily life. The alpha male can eat with or socialize with any other member of the group. Nilgiri langur males are typically more involved in dominance than females, though dominance behaviors in general are not particularly frequent. In addition, aggression during these encounters is avoided. There is little competition for food or mates, and subordinate individuals are careful to avoid potentially harmful situations. Nilgiri langurs therefore have a relatively relaxed daily life. /=\

Nilgiri langurs exhibit territorial (defend an area within the home range), behaviors when confronted by other groups of their species. This defense of territory directly involves only one adult male of each group. Males defend their home areas through physical displays, vocalizations, and chases. Confrontations sometimes escalate to physical violence, leaving both defending males and non-group males with scars on their faces and bodies. In extreme cases, male take-overs and infanticide are known to occur. Such territorial (defend an area within the home range), interactions usually take place in the areas where the home ranges of two or more groups overlap, though Nilgiri langurs usually avoid these overlap areas when the members of other groups are present.

Nilgiri langurs communicate mainly through vocalization. Vocalizations have many different functions, with various calls related to different social situations. Vocal communications are observed during the maintenance of the social hierarchy, during territorial (defend an area within the home range), disputes, as a part of within-group female-female conflicts, and finally for male intervention into such conflicts. Nilgiri langurs also communicate with olfactory, tactile, and visual signals. They are known to engage in mouth sniffing as a part of feeding. This species also exhibits numerous expressions to signal to other species members. Some examples of expressions include a threatening open mouth gesture, a submissive head shaking gesture, a friendly play invitation, and a comforting outstretched hand gesture directed from mothers towards infants. Instances of tactile communication involve biting, licking, embracing, stroking, and slapping.

Nilgiri Langur Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Nilgiri langurs are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They engage in year-round breeding with two periods of increased breeding coinciding with increased food availablity — most notably in May and June, and secondarily between September and November. The regular seasonal rise and depletion of resources might affect females' ability to ovulate and conceive. The average number of offspring is one. [Source: Claire Solomon, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Though there is little documented information about the Nilgiri langur mating system, it is assumed to be similar to that of the Hanuman langur, to which it is closely related. Hanuman langurs exist in uni-male or multi-male groups. The frequency of uni-male groups is dependent on the ability of individual males to defend and retain groups of females. There are small numbers of females in these uni-male groups because larger numbers of females above a certain threshold are able to exert control over the number of males in their groups. Distance between groups, or population density, also has an effect on the proportion of uni-male to multi-male groups. When groups are more spread out, it is more advantageous for a male to remain in his current group than to risk predation while traveling alone to another group. There is evidence that uni-male groups increase female birth rates, indicating that less male-male competition is better for the reproductive success of female langurs.

The gestation period of Nilgiri langurs is believed to be between 140 to 220 days. When newborns are around 10 days old, their mothers permit other females to handle and care for their young. This occurs when the mother wants to feed. One non-maternal female may 'baby-sit' the offspring for up to three mothers. The average weaning age is 12 months. On average males and females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 3-5 years.

Nilgiri langurs do not display strong bonds between mother and young compared to similar species, though nursing lasts almost a year. Occasionally, when young infants are in distress, their mothers will ignore the cries for help in an unusual display of apathy. One hypothesis explains this as a result of the relatively low threat of predators. In all other ways, however, Nilgiri langur mothers are attentive and nurturing. For example, offspring cling to their mothers’ bellies while moving and even jumping, and are also sheltered by their mothers during rainstorms. /=\

Golden Langurs

Golden langurs (Trachypithecus geei) are also called Gee’s golden langur after their discover E. P. Gee. These monkeys have had a number of scientific names. Now they are placed in genus Trachypithecus, but when they were first discovered in 1956 they were put in the Presbytis genus. They have also been placed in the genus Semnopithecus. All three of the genus names fall under the subfamily Colobinae and the family Cercopithecidae (Old World monkey).[Source: Shivani Raval, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Golden langurs are found only in Assam, India and neighboring Bhutan. The area they live is bordered by 1) the foothills of Bhutan to the north, 2) Manas river to the east, 3) the Sankosh river to the west, and 4) the Brahmaputra river to the south. Golden langurs inhabit moist evergreen and tropical deciduous forests as well as some riverine areas. They are dependent on trees and live in the upper canopy and have been found at elevations from sea level to 3000 meters (9843 feet). In Bhutan, they can be found in four national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. In Assam, they inhabit the two wildlife sanctuaries, fragmented reserve forests, proposed reserve forests, and non-forested areas. More than half of the total number of golden langurs living today live in Royal Manas National Park, Black Mountain National Park, Trumsingla Wildlife Sanctuary and Phipsoo Wildlife Sanctuary.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List golden langurs are listed as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. The total population of mature adults has been estimated as 6000–6500. The main reason for their low numbers is the rapid deforestation and degradation of their forest habitat. Although the forests where they live are supposed to be protected, until recently these protections were not strictly enforced. It has been estimated that 50 percent of the langur’s habitat was lost during a period of 12 years in the 1990s and 2000s. Predation by other animals is minimal, likely due to the inaccessible arboreal environment they favor. Sometimes golden langurs raid crops.

Golden Langur Characteristics and Feeding

Golden langurs range in length from 120 to 175 centimeters (47.2 to 68.9 inches), including their tail. The head and body measures from 50 to 75 centimeters (19.6 to 29.5 inches) and the tail ranges from 70 to 100 centimeters (27.5 to 39.4 inches). Their average weight is 8.1 kilograms (17.6 pounds). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Ornamentation is different. The tassle of the tail is notably larger on males than on females. [Source: Shivani Raval, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Golden langurs are easily recognized by the reddish-golden color of their fur — the source of their name. Their body hair ranges from dark golden to creamy buff. Their faces are black and hairless except for a long pale beard. The color of their fur differs on different locations on their bodies; it is slightly darker red on the top and sides and a lighter color underneath. Researchers have observed that the fur changes colors according to the seasons. In the winter it is dark golden chestnut and in the summer it is more cream colored. The color of the young is almost pure white. Color and size varies geographically. Golden langurs in the south tend to be more uniform in color and smaller than those in the northern regions. The overall shape of this monkey is slim, with long limbs and tail. The tail has a tassle on the end.

Golden langurs are both folivores (eat mainly leaves) and frugivores (eat mainly fruit). The eat unripe fruits, young and mature leaves, leaf buds, flower buds, seeds, twigs, and flowers. The prefer young leaves, especially those from Ficus racemosa, Salmalia malabarica, and Adenanthera peuonina.Most langurs are leaf-eating monkeys and have a sacculated stomach made up of different compartments that help to break down the cellulose in the leaves and obtain the maximum possible nutrition from innutritious leaves. [Source: Shivani Raval, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Golden Langur Behavior, Communication and Reproduction

Golden langurs hey are arboreal (live mainly in trees), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Information about the home range of golden langurs is lacking. Within each group, they tend to stay in the same place and do not move far from their home. [Source:Shivani Raval, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Shivani Raval wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Unlike hanuman langurs that are not afraid to live among humans, golden langurs tend to be a shy species that avoids humans. This makes it difficult to observe many of their behaviors and what can be noted may be unnaturally influenced by the presence of humans. It is known that they are mostly active in the early morning and afternoon, which is when they feed. They spend most of their time in the canopy of trees and move around by leaping from branches by pushing off with their hind limbs and landing with all four limbs. They may also move along quadrupedally (using all four limbs for walking and running), both when they descend and on larger branches of trees. /=\

Golden langurs tend to live in groups that range anywhere from four to 40 members, with an average group size of 8. Although not much is known about the social structure of the groups, it has been noted that social grooming is a very important group activity. Golden langurs use social grooming as a way to strengthen the bonds between members of their group. /=\

Golden langurs communicate with vision, touch and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Again, little is known about the communication between golden langurs. What is certain is that vocal communication does exist between members of the species, including loud “whooping” noises heard from the male langurs. In spite of a paucity of information on these animals, we can assume that like other primates tactile communication (such as grooming, mating, aggressive behaviors) and visual signals (such as body postures and facial expressions) play some role in communication also. /=\

Relatively little is known about the reproduction and parental care of golden langurs. Scientists believe that their behaviors in these matters is similar to that that of their close relative hanuman langurs. Golden langurs engage in year-round breeding and are cooperative breeders (helpers provide assistance in raising young that are not their own). Births occur almost year-round. There may be a period of a few months where more births are concentrated, corresponding to changea in climate or food availability. Golden langurs give birth to a single offspring at a time. In Hanuman langurs of the care for the young is provided by the mother and other females in the group. The father has no contact with his offspring.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024