TIBETAN LITERATURE

Tibetan storyteller Tibetan literature includes novels, poems, stories, fables, dramas, collections of Buddhist scriptures and works on history, philosophy, medicine, mathematics, and astronomy. Tibetan religion has infused every part of Tibet's culture including literature. Little of it has been translated to English and even if it was it probably be of little interest to people other than scholars.Because so many Tibetans have traditionally been illiterate, folk tales, histories and legends have traditionally been passed on orally from generation to generation. Guru Rinpoche figures prominently in many of these old tales.Works that have been translated into English include “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” (See Religion); “The Life of Milarepa”, an autobiography by Tibet’s most beloved ascetic; “The Jewel Ornament of Liberation”, a description of the path to enlightenment by one of Milarepa’s disciples.

A large amount of ancient scripts, woodblock, metal and stone carvings have been preserved in the Tibetan areas. Some have been made using ancient block printing techniques. Others were written in Sanskrit on loose leaves. In addition to two well-known collections of Buddhist scriptures known as the Kanjur and the Tanjur, Tibetan literary works include prosody, epics, novels, operas, biographies, poetry, stories and fables and works on philosophy, history, geography, astronomy, mathematics and medicine. Classics works of Tibetan literature include “Thirty Rules of Tibetan Grammar,” the four-part “Ancient Encyclopedia of Tibetan Medicine,” “Feast of the Wise,” the King Gesser Epic (regarded by some as world's longest epic poem ), the legendary-biographical novels “Milarib” and “Boluonai,” “The Sakya Maxims” and “The Love Songs of Cangyang Gyacuo (the Sixth Dalai Lama).” [Source: China.org]

In their book “Tibetan Literature,” Wei Wu and Yufang Geng wrote: “The severe conditions that often imperil survival on the towering Tibetan Plateau have helped for it unique culture, along with its close ties with the Central Plains. Tibetan literature not only reflect the life, thoughts, and esthetics of different levels at various phases in Tibetan history, but also provides an important reference for the study of the Tibetan language and origin of words, social history, religion and belief, morality and behavior, the spiritual world, as well as local conditions and customs. [Source: Tibetan Literature by Wei Wu and Yufang Geng. 2005]

Tsangyang Gyatso (1683-1706), the sixth Dalai Lama, was a poet whose love songs in Tibetan verse are much beloved among Tibetans and Han alike. Tsangyang Gyatso’s writing is considered by some to be part of the Chinese literary tradition. This is ironic considering he was kidnapped and deposed in a series of murky events, possibly with the consent of Qing Dynasty Chinese Emperor Kangxi. [Source: Bruce Humes, Ethnic ChinaLit, December 17, 2014]

See Separate Articles TIBETAN CULTURE: HISTORY, STEREOTYPES AND KEEPING IT ALIVE factsanddetails.com; TIBET, SHANGRI-LA MYTH AND WESTERN ACTIVISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; KING GESAR: TIBET’S GREAT HEROIC EPIC factsanddetails.com; WOESER: HER LIFE, POEMS AND ACTIVISM factsanddetails.com OPERA AND THEATER IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; FILMS ABOUT TIBET AND THE HIMALAYAS factsanddetails.com; PEMA TSESDEN AND FILM IN TIBET factsanddetails.com;TIBETAN BUDDHIST TEXTS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Series of Basic Information of Tibet of China--Tibetan Literature” by Wu Wei and Geng Yufang Amazon.com; “A Classical Tibetan Reader: Selections from Renowned Works” by Yael Bentor Amazon.com; “The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet” Amazon.com; “Tibetan Folktales” by Haiwang Yuan , Awang Kunga , et al. Amazon.com; “Wonder Tales from Tibet” by Eleanore Myers Jewett Amazon.com; “Old Demons, New Deities: Twenty-One Short Stories from Tibet” by Tenzin Dickie Amazon.com; “South of the Clouds: Tales from Yunnan”by Lucien Miller, Guo Xu, Xu Kun Amazon.com; “The Epic of Gesar of Ling: Gesar's Magical Birth, Early Years, and Coronation as King” by Robin Kornman, Lama Chonam, et al. Amazon.com; “Milarepa: The Magic Life of Tibet's Great Yogi” by Eva Van Dam Amazon.com; “Tibet's True Heart: Selected Poems” by Tsering Woeser Amazon.com; “Voices From Tibet: Selected Essays and Reportage” by Tsering Woeser, Wang Lixiong, et al. Amazon.com; “Yeshe: A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities” was launched in August 2021. It publishes English translations of short stories, poetry, and essays by Tibetan writers originally written in Tibetan and Chinese, as well as interviews, book reviews, and academic articles on literature, art, and history.

Development and Characteristics of Tibetan Literature

On the developing process and characteristics of Tibetan Literature Wei Wu and Yufang Geng wrote “1) Strong Temporal Background: Tibetan folklore and authorial literature provide living pictures of Tibetan life and development at various stages in history. The literature of history, biography and drama was especially outstanding. A General Record of Tibetan Kings and A Feast of Scholars are supreme examples of history-themed literary works, and the Biography of Milha Raba leads in biographical literature. The dramatic eight major Tibetan opera items are still popular today. [Source: Tibetan Literature by Wei Wu and Yufang Geng. 2005 ^*^]

“2) Folklore and Authorial Literature Promoted Each Other: The folklore and authorial literature were the two necessary wings of Tibetan literature. Among the folklore, the great epic Biography of King Gesar was known publicly as the culmination of Tibetan literature and a masterpiece among world literary works. It was also a encyclopedia for researching Tibetan social life, national history, economic culture, class relations, national intercourse, ideology, morality, customs and habits, as well as religion and belief.^*^

“3) Art, History and Philosophy Proceed Side by Side: Over quite a long period, Tibet had no the concept of literature in today's sense of the word, so it had relatively few pure literary works. These were generally a fusion of history and philosophy, such as the Biographies of Tubo Kings found in Dunbhuang, the historical works like Records of Bamya Monastery, Collected Works of Manyi, Five Volumes of Biography, biographical works like Biography of Marba, Biography of Riqoinba, Biography of Riqoinba, Biography of Tongdong Gyibo, Biography of Pholhanas, and gnomic verses like Sagya's Mottoes, Sayings of Gedain, Mottoes on Water and Trees and How the King Cultivates His Personal Virtues. These deeply influential works handed down from ancient times were not pure literature in the literal sense, but were recorded in Tibetan literary history due to their literary grace, splendid rhetoric, lively plots and their mix deal of folk songs, proverbs and folk stories related to the seeking of Tao (The Way). ^*^

“4) Close Relation With Religion: Given the long history of Tibetan Buddhism and the implementation of a combined religious and temporal administrative system, in addition to some writers either being religious followers or even eminent monks, Tibetan literature, especially authorial literary works, contains a strong religious imprint. Some works were originally drawn from Buddhist tales. Iron certificate bearing golden words in Pagba script, reading: “Relying on the imperial edict issued by the emperor and blessed with the strength bestowed by the Heaven, the certificate holder would punish whoever disobeys”. This is a certificate the Yuan emperor issued to leader of the Sagya Sect.” ^*^

Preservation of Tibetan Literature

“The value of Tibetan literature is two things,” David Germano, a professor of Tibetan studies at the University of Virginia, told the New York Times. “First of all, it’s one of the four great languages in which the Buddhist canon was preserved.” (The others are Chinese, Sanskrit and Pali, an extinct language of India.) “In addition to the scriptural canon,” he said, “there were histories, stories, autobiography, poetry, ritual writing, narrative, epics — pretty much any kind of literary output you could imagine. So the second value of the Tibetan canon is it’s one of the greatest in the world.”

The canon was imperiled after China invaded and occupied Tibet in the 1950s. Though fleeing refugees managed to smuggle some books out, the Chinese destroyed a great many others.”With the close of the Cultural Revolution, you essentially lost much of the Tibetan Buddhist literature,” Professor Germano said. “It was lost to the war; it was lost to the destruction of the monasteries, libraries and collections of books in Tibet that were systematically sought out and burned during the Cultural Revolution.”

E. Gene Smith, a Utah native who died in 2010, amassed the largest collection of Tibetan books outside Tibet and put much of it online through the Tibetan Buddhism Resource Center, which he founded. Beginning I earnest when worked for the Library of Congress in India, according to New York Times, he “acquired as many Tibetan books as he could for the library, seeking out Tibetan refugees in India, Nepal and Bhutan and earning their trust. Most of the books he collected were either hand-lettered manuscripts or had been printed in the traditional manner, using carved wood blocks. (Tibet had no printing presses.) Often, a book he obtained was the only known copy in the world.”

Robert Thurman, of Columbia University studied to become a Tibetan Buddhist monk after he ended a marriage to an heiress after deciding that he didn’t want to spend his life, as he told the Times, “drinking Champagne and staring at Rouaults.” He friendship with the Dalai Lama dates back to the 1960s when they met in India.

Tibetan Folklore

According to one Tibetan myth, a divine monkey married a female monster in Yarlung Valley long ago. They gave birth to six children whose descendants spread over the earth but had a hard life. They lived off of wild fruits of the forest. Then the monkey gave them seven kinds of grain, and they learned how to farm and began to speak.

In their book “Tibetan Literature,” Wei Wu and Yufang Geng wrote: Tibetan authorial literary writing has enjoyed a long history, with abundant works, unique style, skillful practice, a profound base and wide influence, based on its strong roots in folklore. There were a lot of authorial works that took the reference of folklore, for instance, the Songs of Milha Raba based on Tibetan folk songs, A General Record of Tibetan Kings, Annotated Book on Tibetan Kings and A Feast of Scholars injected with such fables as how the macaque became human, as well as the stories about Princess Wencheng and Princess Jincheng, the tale of building the Jokhang Monastery, etc; the Love Songs of Cangyang Gyaico and the eight major Tibetan opera items handed down through the generations Prince Norsang, Princess Wencheng, Girl Namsa, Baima Wenba, Denyu Toinzhu, Zholwa Sangmo, Sugyi Nyima and Trimai Gundain adopted all materials from historical tales, folk tales and sutras. [Source: Tibetan Literature by Wei Wu and Yufang Geng. 2005 ^*^]

“Famous old Tibetan folk stories include: “The Song of Siba Butchering Cows, the Biographies of Tsampo Kings, the Story of Songtsan Gambo Greeting Princess Wencheng, as well as the rare Tibetan literary works unearthed at Dunhuang, the Records of the Banya Monastery, etc., were mythic stories of the important figures” in and issues in primitive and later feudal society. The works reflecting the days when several kingdoms thrived. The birth of a number of works handed down from ancient times, including the Collected Works of Manyi and the Five Volumes of Biography that mainly described the social history and culture of the Tubo Kingdom; the Songs of Milha Raba that focused on Buddhist teachings; the Sagya's Mottoes targeted at learning, pursuit of politics and the ways getting along with others; and especially the Biography of King Gesar, the epic ballad about a national hero, helped Tibetan literature to spring into full flower.” ^*^

King Gesar: Tibet’s Great Heroic Epic

The Gesar Epic of Tibet is regarded as the world’s second longest book in the world after the India epic The Mahabharata. It is a heroic tale created by the Tibetans from a collection of ancient legends, myths, verses, proverbs and various other folk cultures of Tibet. Originating via folk oral traditions, King Gesar was passed down from generation to generation orally in a combination of song and narration. Thought to have be written down in the 11th century, "Biography of King Gesa'er" is a called "Jiawugesa'ertena" or "Gesa'er'azhong" in Tibetan, and is widely read over Tibetan regions, including Tibet, Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, Yunnan, and the Tu and Naxi region. There are at least 70 versions of it, with some having over one million lines. [Source: Tibetravel.org ; Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

The Tibetan epic is believed to have been formed between around 200 B.C. or 300 B.C. and A.D. 600. Even after it was written down, folk balladeers continued to pass on the story orally, which enriched the plots and embellished the languages. The story gradually become the story known today and was very popular in the early 12th Century. The epic began to be compiled mainly by the monks of Nyingmapa (Red Sect of Tibetan Buddhism) in about the 11th century mainly in hand-written books.

The unabridged King Gesar has been collected in more than 120 volumes, with more than one million verses (over 20 million words) — 25 times the length of the Western classic, Homer's Iliad. The epic has been translated into Chinese and the languages of other Chinese nationalities as well as English, French, Russian, German, Indian and other foreign languages. It has now become a subject of study and has been discussed as a topic in the international seminar. The King Gesar’s story has been the the subject of stage operas and serial TV dramas.. ~

See Separate Article KING GESAR: TIBET’S GREAT HEROIC EPIC factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Literature and China

In their book “Tibetan Literature,” Wei Wu and Yufang Geng wrote: “After the establishment of new China, especially in late 1978, when the Central Government introduced the reform and opening-up program, Tibetan literature achieved much; Tibetan and Chinese literary works developed equally, authorial literature and folk literature ran side by side, literary writing and criticism made simultaneous progress, and poetry, the novel, prose, drama, movies as well as quyi (Ghinese folk art forms including ballad singing, story telling, comic dialogues, clapper talk, cross talk, etc.) bloomed at the same time. The achievement of novel was especially eye-catching. [Source: Tibetan Literature by Wei Wu and Yufang Geng. 2005 ^*^]

“Tibet has been dealing with various ethnic groups in inland China and the surrounding areas in politics, economy and culture since ancient times. During the Tubo Kingdom in the 7th century A.D., the language scholar Tomi Sangbozha invented the Tibetan script according to the characteristics of Tibetan language, after investigating several kinds of Indian scripts. Soon after, some Tibetan scholars successfully translated Canons of Yao and Shun-Book of History, Military Strategy of the Warring States and some famous articles forming part of the scriptures of Han Chinese Buddhism into Tibetan script. ^*^

“In the early 13th century, the great Tibetan scholar Gonggar Gyaincain introduced into Tibet the Indian rhetorical masterpiece Mirror of Rhetoric. Later, on the strong call of Pagba, it was fully translated into Tibetan script. Hence, Tibetan scholars studied and applied it, popularizing the study of good articles and use of carefully considered rhetoric for a certain period of time. The successful works were the History of Kings and Ministers of the 5th Dalai Lama and the Youth Darma of Cering Wanggyia. ^*^

“After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, communication between the Tibetan races and other ethnic groups were increasing. The four famous classical Chinese novels, Water Margin, Three Kingdoms, A Pilgrimage to the West and A Dream of Red Mansions, were completely or partially translated into Tibetan. Other world-renowned works were also translated in succession. Meanwhile, Tibetan literary masterpieces, either classical or modern, were translated into Chinese, English, French, German, Japanese, Russian, Hungarian, Czech and other languages, which aroused great interest among readers of different races and nations, enabling Tibetan literature to make further progress. ^*^

Modern Literature Related to Tibet

Tsering Döndrup is a Mongolian-Tibetan author from Amdo (Qinghai Province). He is one of the most popular and acclaimed authors writing in Tibetan today, and is renowned for his humorous and penetrating critiques of contemporary Tibetan society. Of particular interest is the manner in which he treats the experiences of Tibetans in modern China, including the major impact of Chinese on the modern Tibetan language. “The Handsome Monk and Other Stories”, by Tsering Döndrup, is available in English. It is published by Columbia University Press.

In the early 2010s, thrillers and mysteries connected to Tibet were all the rage in China. He Ma’s The Tibet Code reportedly sold over 3 million volumes sold and spawned a number of thrillers and mysteries driven by a similar fascination with Tibetan history, religion and relics. The popular three-volume Tibetan Mastiff by Yang Zhijun was made into an animated film co-produced by a Sino-Japanese partnership. He Ma and Yang Zhijun are both Han Chinese writing about Tibet. [Source: Bruce Humes,Altaic Storytelling, May 18, 2014]

“The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa” is a book by the Chinese writer Chan Koonchung on Tibet. He wrote on the PEN Atlas: “The main protagonist of my new novel, Champa, is a young, modern, Chinese-speaking Tibetan man. He grew up in the cosmopolitan city of Lhasa. The novel in this sense is about Tibetan and Han relationships, but it will defy easy stereotyping. It is one of the intentions of the novel to be as uncompromisingly realistic and anti-romantic as possible. [Source: Chan Koonchung, English Pen, June 26, 2014]

In 2012, “I started to work on a new story, Luo Ming or ‘Naked Life’, renamed for its English edition as The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa the Driver. The year 2012 was difficult for Tibetans in China, and I wanted a raw and pungent way to express my feelings, and the main protagonist needed to be a Tibetan. Champa, the main protagonist, has two very different but equally bumpy relationships with Han women. He was a tourist driver before he became the ‘kept man’ of an attractive, affluent middle-aged Han businesswoman in Lhasa. Life was good for Champa until he fell for an enigmatic young woman, an event which made him give up on his cushy Lhasa life and drive to Beijing, his dream city. Nothing in Beijing turned out as expected. I intended to capture at least a fraction of the complicated relationships between the Han Chinese and Tibetans and cut across five kinds of stereotypes when it comes to Tibet and Tibetans:

Chan Koonchung was born in Shanghai and raised in Hong Kong. He was a reporter at an English newspaper in Hong Kong before he founded the influential magazine ‘City’ in 1976, where he was the chief editor and then publisher for 23 years. He is also a screenwriter and film producer of both Chinese and English-language films. He is fluent in English, and now lives in Beijing. The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa the Driver was published in the UK by Doubleday. The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa is translated by Nicky Harman.

Chinese Crackdowns on Tibetan Writers

In August 2015, Chinese Authorities closed down Choemei (also spelled Chodme), or “Butter Lamp” in Tibetan, a website founded by a group of young Tibetans that served as a forum for news and literary writings in Tibetan. It was one of the oldest Tibetan websites promoting culture and literature. According to Radio Free Asia: Writer Kunchok Tsephel established the website in 2005 with his own money as a joint venture with young poet Kybchen Dedrol in Machu (in Chinese, Maqu) county of Kanlho (Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu province, according to the Tibetan source and information on the website of the nonprofit, nongovernmental organization Free Tibet. [Source: Radio Free Asia, August 25, 2015]

“Chinese authorities had shut down the website on other occasions as well, according to Free Tibet. In February 2009, they had searched Tsephel’s home and seized his computer, mobile phone and other belongings, and took him into custody. In November 2009, the Intermediate People’s Court in Kanlho sentenced him to 15 years in prison for “divulging state secrets” during a closed-door trial.

“Authorities previously had detained and tortured Tsephel for two months in 1995 for his alleged involvement in political activities, according to the Free Tibet website. Authorities targeted many other contributors, especially Tibetans, who wrote articles for the website and warned its owners about accepting reports that went against Chinese policy in Tibetan-populated areas, he said. The website carried news and other reports, both written and audio, as well as video stories, music and contemporary writings.

Alai

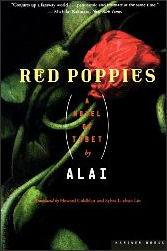

Alai, a Tibetan writer who goes by one name, is from the Tibetan area of northwestern Sichuan. Alai emerged in 1998 with his debut novel “Red Poppies”, now available in English. Its original title in Chinese is “The Dust Settles”, and it is also set in Tibet. Alai’s writing career started in the 1980s, first with poetry and then with fiction. He is now president of the Sichuan Writers Association.

Alai was born in 1959 in the Gyarong Tibetan ethnic community that inhabits Aba Prefecture, Sichuan Province. Liu Yuanhang wrote in News China: He was raised in a close-knit family: His mother is Tibetan and his father Hui Muslim. Before writing novels, Alai was a poet. A diehard follower of Pablo Neruda and Walt Whitman, he was passionate about poetry in his youth. [Source: Liu Yuanhang, News China, September 2019]

“Alai graduated from a teacher training college and taught in a rural school for five years before landing a job at the Aba Cultural Bureau as an editor for a local literary journal. He began writing poems in 1982 and published his first anthology The Lengmo River in 1989. He was 30 “My youth was all about writing poetry in loneliness. I came from a very poor family and suffered from a chronic illness. As a teacher, when the bell rang, I had to be in class but most of the time I kept myself invisible from others and indulged in reading, music and writing poems,” Alai told NewsChina.

“But in the years following The Lengmo River, Alai gradually felt that poetry was no longer enough to balance his thoughts with the rapidly changing and increasingly complex world. He increasingly could not turn a blind eye to social issues. “A feeling of emptiness haunted me for a long time and I couldn’t get rid of it. The old passion gradually turned into suspicion,” Alai said. Alai began to contemplate his ethnic identity and Tibetan history and culture. Outsiders describe Tibet with an air of mystery and romance, while Tibetan history is framed in the official narrative. For Alai, neither provides a complete picture. “He gave up writing poems and began researching local records and the family histories of 18 Tibetan chieftains, which laid the foundation of Red Poppies

“In 1998, Alai became chief editor of Science Fiction World, a magazine based in Chengdu. Running a commercial magazine, Alai had to interact with many people, such as writers, sponsors, advertisers, contributors, publishers and distributors. But through his efforts, Science Fiction World became China’s most influential sci-fi magazine — it now has a circulation larger than any sci-fi magazine in the world.

“Alai’s focuses do not stop with Tibetan history. As China marched toward a market society under reform and opening- up, Alai began to explore how commercialism had reshaped the relationship between urban and rural areas, and its effect on traditional values. “Commercialism is a much more powerful force than ideology. In the past, people could fight against ideological control, and they were seen as heroes even if they failed. But in a commercial society, there’s no chance for you to fight against its hidden rules. If you don’t follow them, you’ll be a useless person left behind, you’ll be a loser,” Alai told NewsChina.

Red Poppies and Alai Books

Red Poppies, Alai’s first and most famous novel, came from researching of local records and the family histories of 18 Tibetan chieftains. Liu Yuanhang wrote in News China: Red Poppies tells a sweeping epic tale about the final years in the history of the Gyarong-Tibetan chieftain system from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century. It was based on a story Alai wrote in the 1980s about a legendary Tibetan sage named Aku Tongpa, who masked his wisdom and intelligence behind a facade of idiocy. [Source: Liu Yuanhang, News China, September 2019]

“In Red Poppies, the character became Young Master, a chieftain’s son who despite his mental deficiencies, possessed great wisdom and a supernatural foresight that revealed the rise and fall of his family and other chieftains. Published in 1998, Red Poppies was a bestseller. It won the 2000 Maodun Prize, China’s highest literary award. At 41, Alai was the youngest writer in China to win the award.

“In 2005, Alai published his six-volume novel “The Empty Mountain”, which tells about the lives of the last Tibetan hunters and depicts the changes that have taken place in Tibet during China’s three decades of reform and opening-up. Also known as “Hollow Mountain”, the book is about a Tibetan village in the middle of a 50-year tumultuous transformation and is seen as a microcosm of rural China as a whole. Alai told the China Daily, “The protagonist of my novel is the village, not a person, and this village is broken and unstable, with an array of people on center stage at various times.” Alai won the title of “Outstanding Author of 2008," the year the last installment of "Empty Mountain" was published. [Source: Raymond Zhou, China Daily, April 15, 2009]

In his novella “The Shade of the Cypress on the River”, Alai writes about the extinction of a rare kind of cypress in a village after its highly inflated price tempts the villagers to cut them all down. Another novella, “Winter Worm, Summer Grass”, focuses on how the trade in Cordyceps, a caterpillar fungus found on the Tibetan Plateau prized for its medicinal value, changes a Tibetan village. “The desires behind consumerism have forever altered people’s thinking. I think it’s a much more crucial problem than ethnic relations,” he said.

“Cheng Depei, a noted literary critic and Lu Xun Literary Prize winner, told News China that the force of nature plays a central part in Alai’s novels. “The most striking feature in Alai’s writings lies in his focus on the relationship between human and nature. He sees a huge gulf between human and nature, and in this gulf is the collected philosophy and literature of humankind. In the Cloud provides a special viewpoint to contemplate the relationship between them. Humans never quite balance these two — if one cares too much about that world, he may inevitably resort to religion, while if he cares too much about this world, he would turn into a very petty secularist,” Cheng said at the event.

Alai and the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake

Liu Yuanhang wrote in News China: “Alai was working on his mythological novel The King of Gesar at his home in Chengdu, Sichuan Province when the ground violently trembled under his feet. “At that moment I was writing about the fury of the gods, who make the entire world quiver in fear. It took me a few seconds to judge whether the violent quake was real or my imagination. I felt the tremor instantly spring up from the ground to my desk and it almost flung me to the floor. Then I realized it was not from my hallucination. It was a real earthquake,” reads the preface of “In the Cloud” (2019). [Source: Liu Yuanhang, News China, September 2019]

“Eleven years earlier, China was traumatized by one of the worst earthquakes in the nation’s history. At 2:28 pm on May 12, 2008, powerful shock waves erupted from the epicenter in Wenchuan County and instantly spread across the province. The magnitude-8 quake would leave 87,000 people dead, 370,000 injured and five million homeless. The provincial capital of Chengdu, where Alai lived, was the closest major city to the earthquake’s epicenter.

“Alai joined in rescue efforts, where he witnessed suffering and death. A decade later, the writer said a flood of memories from these experiences suddenly overcame him. Then he forced himself to face his trauma and write his story about his feeling and experience. Wenchuan is located in Aba Prefecture. After the quake, the only fortunate news for the writer was that there was no one killed in his home village.

“At 49, he volunteered for rescue teams, but was turned away because of his age. He headed in alone. Alai loaded his jeep with large quantities of food and water from the supermarket. He drove into the disaster-stricken area only for two falling rocks to hit his car. After he arrived, the writer joined rescuers and distributed the water and food to people in need. The day was hot and the air thick with the stench of rotting corpses. He had to wear three face masks to cope with the smell. “We dug a two-meter-wide pit, placed one layer of bodies, and a layer of dirt and lime above it, and then another layer of bodies,” Alai told NewsChina. “The whole thing was too much to bear, so I had to stop for a while. I returned to my car and played Mozart’s Requiem in D Minor at low volume. It was pitch dark outside. The sky was full of stars. In an instant I felt the night was so beautiful. And so was Mozart’s Requiem. Some strangers came over and silently listened with me. When the music was over, they left,” he recalled. “I thought if I was about to write about death, I hope my writing would show the power I felt in the Requiem,” he said.

“Soon after the earthquake, many noted writers wrote essays and books about the disaster. But Alai rejected requests from media and publishers to write on the subject. “After having witnessed so much, I had a strong urge to write something. But every time I attempted to write, I repeatedly asked myself whether I had found the most appropriate way to tell the story. I’d been waiting for the proper time for so many years,” he told NewsChina. On May 12, 2018, on the 10th anniversary of the earthquake, a sudden surge of memories engulfed him. He began to write. “I kept myself alone in the study that day. I wrote and wrote with tears rolling down my face,” Alai said. He wrote at a feverish pace, finishing the entire novel in five months.

Alai told NewsChina that In the Cloud was initially inspired by a series of photos taken by his friend, a professional photographer. Among them was a photo of a local shaman holding a drum and standing before the ruins of his village. The shaman told the photographer he had returned to the ruins for one reason: “The government takes care of the living, while I take care of the dead.” The story impressed Alai so deeply that he based Aba, the protagonist from In the Cloud, on that shaman.

“The story is set in Yunzhong, which translates to “in the cloud,” a Tibetan village that had stood for a millennium. Aba comes from a long line of Bon shamans, an ancient religion based in Tibetan Buddhism that also involves animism and ancestor worship. But he did not take up the priesthood, instead choosing to finish middle school and become the first in his village to work at a hydroelectric power plant. The 2008 Sichuan earthquake devastated the ancient village, killing over 80 people. Geologists predicted that the mountain on which the village stood would eventually slide into the nearby Minjiang River. Authorities ordered all the villagers to leave the mountain, the home of their ancestors and the mountain god they worshipped, for a safer area in the plains. Three years later, Aba began feeling a spiritual force drawing him back to the old village. He returned to his lost hometown with two horses and lived there for six months. Answering his family calling, Aba held rituals for the 36 families lost to the earthquake. Every day, before the ruins of every home, Aba would burn incense, chant and dance to comfort the souls of the dead. “I’ve seen many people like this. Many don’t have a clear sense of their responsibilities. They are not aware of their own role and just work and live with no particular purpose. But when disaster comes, something inside them is suddenly awakened, and in extreme conditions they realize their mission and responsibilities,” Alai said during a June 30 event promoting his book in Shanghai.

Alai on Artistic Quality

Alai is a National People’s Congress deputy as well as chairman of the Sichuan Writers' Association. He told the China Daily: contemporary publishing circles suffer from an erroneous belief that sales are a barometer of a book's popularity. So to please the public, some writers seek popularity through creating vulgar works that "undermine the artistic nature of literature". [Source: Liu Lu, China Daily, March 20, 2012]

"The market-oriented approach does stimulate the creativity of Chinese writers, which has greatly contributed to today's literary boom," Alai says. "But there are serious problems behind this." The novelist says that while profitability is an indicator of success, a book's spiritual and artistic value is more important. "The development of the cultural industry cannot simply follow the development routes of other industries and be solely profit-oriented. In my opinion, a good literary work should not only be readable but also put an emphasis on artistic exploration and delve deeper into human nature and the diversity of culture."

Alai says the lack of spiritual qualities in works by Chinese writers means they are not as influential as they could be internationally. "Foreign publishing houses are looking for outstanding literary works from China that allow overseas readers to gain a better understanding of the country," he says. "They do not love just entertaining works."

More foreign works are imported than Chinese works exported, he adds. "If Chinese writers want to improve their international prestige, they must improve their literary quality," Alai says. He also urges the authorities to attach more importance to the export of Chinese literary works, because "they have a more lasting and far-reaching influence in regard to constructing China's soft power and offer a gateway for foreign readers to have a deeper understanding of the diversified aspects of China. When more true-to-life literature is created in China, Chinese literature will surely be more influential."

Shangri-La and Lost Horizon

The term "Shangri-la" was coined by English novelist James Hilton in his novel “Lost Horizon”. It refers to a beautiful mystical place discovered by four Westerners who crash land in an airplane there. “Lost Horizon” was published the year that Hitler rose to power and topped the best seller list for two years. Frank Capra did a 1937 film version of the novel, which starred Ronald Colman and Jane Wyatt. It won several Oscars but seems quite silly and dated when viewed today.

In “Lost Horizon”, Shangri-la is a Buddhist monastery in a Tibetan valley where people enjoy a happy trouble-free life and live to be more than 200 years old by doing yoga, breathing in the mountain air and eating tangatseberry (a native herb).

The monastery boasts central heating, European plumbing, an Oriental garden and a first-rate collection of Chinese art. It is run by a 163-year-old Catholic priest who keeps a file of the London Times and maintains a library. The residents spend their free time learning new languages, mastering Chopin piano pieces, contemplated eternal questions and bathing in green porcelain tubs.

See Separate Article TIBET, SHANGRI-LA MYTH AND WESTERN ACTIVISM factsanddetails.com

Heinrich Harrer and Seven Years in Tibet

Heinrich Harrer

“Seven Years in Tibet”, the film starring Brad Pitt, was based a 1953 autobiographical book by Heinrich Harrer (1912-2006) , a selfish, real-life Austrian mountain-climber who befriended the Dalai Lama and became his tutor. Harrer had been a Nazi and a S.S. officer before setting off for Asia on a climbing expedition, leaving his pregnant wife behind. The book “Seven Years in Tibet” has sold 4 million copies and been translated into 48 languages. [Source: Lewis Simmons, Smithsonian magazine, H.G. Bissinger, Vanity Fair, October 1997]

Harrer befriended the Dalai Lama and became his tutor. Featured in the film “Seven Years in Tibet”, the friendship began when Harrer was 37 and the Dalai Lama was 14. Harrer taught the Dalai Lama English and geography, informed him about Western customs, and explained the best he could how planes flew, tanks worked and atom bombs were detonated. Harrer and the Dalai Lama shared the same birthday, July 6.

Describing the first time he saw the Dalai Lama in a procession, Harrer wrote: "And now approached the yellow, silk-lined palanquin of the Living Buddha, gleaming like gold in the sunlight. The bearers were six-and-thirty men in green silk coats, wearing red plate-shaped caps. A monk was holding a huge iridescent sunshade made of peacock's feathers over the palanquin. The whole scene was a feast for the eyes — a picture revived from a long-forgotten fairy tale of the Orient." Anything the Dalai Lama touched, Harrer said, was seized as an auspicious object.

See Separate Article FILMS ABOUT TIBET AND BY TIBETAN DIRECTORS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Purdue University, Cosmic Harmony, the film Kundun

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022