TIBETAN CULTURE

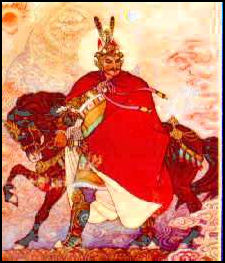

King Gesar, the subject

of many stories and dramas

Tibet has its own language, culture, customs, alphabet, legends, music, government, calendar and religion. Traditionally, art, culture, religion and everyday life have been inextricably intertwined in Tibetan Buddhism.Tibetan culture has gone underground to a large extent under Chinese occupation and is arguably more alive outside of Tibet in places like Ladakh, Bhutan and Sikkim. Tibetan scholars that want to study their classical literature often have to do so with Chinese translations.

Many traditional Tibetan arts — such as religious paintings, sculpture, carved altars, religious texts, altar implements, statues with precious metals inlaid with gems, appliqued temples hangings, operatic costumes, religious performances, religious music, and religious singing — are forms of religious worship, many of them carried out by monks at monasteries.

The Tibetans have their own theater companies, opera, music and ballet performers, broadcasting stations, and film studio. Many Tibetan newspapers, magazines, and books are published each year. Well-known Tibetan intellectuals include Jamyang Kyo, a writer and researcher that was arrested in April 2008 and taken away from her office in a state-owned television station in Xining in Qinghai Province; and Jamyang Kti, a well-known singer and television presenter who has written extensively about women’s rights. Among the Tibetans that gained some notoriety in the West were Chogyam Trunga, the guru of the beat poet Allen Ginsberg.

Tibetan Cultural Sites: Tibetan Cultural Region Directory kotan.org ; Tibet Online on Culture tibet.org/Culture ; Mystical Arts of Tibet mysticalartsoftibet.org ; Tibetan and Himalayan Library thlib.org ; Wikipedia article on Tibetan Literature Wikipedia ; Tibetan Studies and Tibet Research: Tibetan Resources on The Web (Columbia University C.V. Starr East Asian Library ) columbia.edu ; Tibetan and Himalayan Library thlib.org Digital Himalaya ; digitalhimalaya.com ; Center for Research of Tibet case.edu ; Tibetan Studies resources blog tibetan-studies-resources.blogspot.com

articles on TIBETAN CULTURE factsanddetails.com factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; KING GESAR: TIBET’S GREAT HEROIC EPIC factsanddetails.com; WOESER: HER LIFE, POEMS AND ACTIVISM factsanddetails.com TIBETAN ART factsanddetails.com; MUSIC IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN DANCE factsanddetails.com; OPERA AND THEATER IN TIBET factsanddetails.com TIBETAN ARCHITECTURE: TEMPLES, PALACES, STUPAS factsanddetails.com FILMS ABOUT TIBET AND THE HIMALAYAS factsanddetails.com; PEMA TSESDEN AND FILM IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; SPORTS AND RECREATION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com HORSE RACING AND YAK RACING IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Tibetan Life And Culture” by Eleanor Olson Amazon.com; “Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan Culture A Collection of Essays” by Toni Huber Amazon.com “Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture by Ronald Davidson Amazon.com; “Tibet: A History Between Dream and Nation-State” by Paul Christiaan Klieger Amazon.com; “The Myth of Shangri-la: Tibet, Travel Writing and the Western Creation of Sacred Landscape” by Peter Bishop Amazon.com; “Shambhala: The Fascinating Truth behind the Myth of Shangri-la” by Victoria LePage Amazon.com; “Lost Horizon” by James Hilton, Amazon.com; “Tibetan Nomads: Environment, Pastoral Economy, and Material Culture” by Schuyler Jones and Ida Nicolaisen Amazon.com;

Chinese and Tibetan Culture

Robert A. F. Thurman wrote: “Culturally, Chinese people tend not to know the myths, religious symbols, or history of Tibet, nor do Tibetans tend to know those of the Chinese. For example, few Tibetans know the name of any of the Chinese dynasties, nor have they heard of philosophers Confucius or Lao-tzu, and fewer Chinese know of the Yarlung dynasty, or have ever heard of Songzen Gampo (emperor who first imported Buddhism, seventh century), Padma Sambhava (eighth century religious leader), or Tsongkhapa (philosopher 1357–1419). Tibetan and Chinese clothing styles, food habits, family customs, household rituals, and folk beliefs are utterly distinct. The Chinese people traditionally did not herd animals and did not include milk or other dairy products in their diets; in fact, the Chinese people are the only large civilization on the earth that was not based on a symbiosis of upland herding people and lowland agriculturalists. Hence they were the only culture to create a defensive structure, the "Great Wall" in order to keep themselves separate from upland herding peoples such as Tibetans, Turks, and Mongolians. [Source: Robert A. F. Thurman, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

The Chinese artist Zhang Huan, who visited Tibet in 2005, told the New York Times the trip irrevocably altered his Zhang’s thinking and his art making. “One day in Lhasa, I got up at 4 a.m. and went to the Jokhang Temple, the biggest one in Tibet, and I saw men and women already lining up for miles,” Mr. Zhang said. He said he was amazed by the sight of pilgrims crawling to the site in the middle of traffic, in a seeming clash between modernity and ancient tradition. “I have been to the most famous museums in the world, and I have never seen a sight as striking as this,” he said. [Source: Barbara Pollack, New York Times, September 12, 2013]

Stereotypes About Tibet

Tibet has one of the world’s most romanticized cultures. Elliot Sperling of Indiana University's Tibetan Studies Program told PRI"There is a tendency among many people who are interested in Tibet to see Tibet as frozen in this sort of idealistic Buddhist, or even folk, kind of culture. But all culture is dynamic." [Source: Matthew Bell, PRI, February 11, 2014]

On the five stereotypes that shape views of Tibet, Chan Koonchung, a Chinese writer heo has written about Tibet, wrote: 1) The romantic stereotype –Tibet as Shangri La, an exotic, timeless touristy region of simple, peaceful folks. 2) The spiritual stereotype – Tibet as the spiritual Buddhist holy land. Tibetan Buddhist gurus have many followers in other parts of China. 3) The patronising stereotype – Tibet is pre-modern, China is modern. The Communist Party liberated Tibet from medieval backwardness. Tibet depends on aid from the Chinese state. China’s affirmative action policies are beneficial to the Tibetans, maybe too generously so. 4) The statist stereotype – Tibet has always been a part of China from time immemorial. Foreign imperialists are always there trying to encourage Tibetan separatists to divide the Chinese motherland.

5) The victim stereotype – Tibetan culture is under threat, all because of the Chinese rule: non-Tibetan migrants, ‘Han-ification’, assimilation policies, bureaucratic nepotism and state violence. But traditional culture is also changing inside Tibet because many Tibetans want modernisation and welcome economic growth. Many Tibetan families urge their children to learn Chinese and young Tibetans love hybridised popular culture. (Though, of course, I am not unsympathetic to this victim stereotyping because Tibetans are now indeed a minority culture under stress.)

See Separate Article TIBET, SHANGRI-LA MYTH AND WESTERN ACTIVISM factsanddetails.com

History of Tibetan Culture and Arts

Tibetan art and culture is closely linked with religion. Early Tibetan art and culture was closely bound up with the aboriginal Bon religion, while later art and culture has been closely associated with Tibetan Buddhism. Bon was the main aboriginal religion of the ancient Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. It is said to have originated in the 5th century B.C. with Shenrab Miwoche, the prince of Zhang-zhung kingdom in western Tibet. Around the first century A.D. the religion began to spread eastward until it became widely practiced in the Tsang region and Lhasa region. Bon is still practiced today. It embraces pantheism and beliefs that “everything has a soul”. Bon deities include supernatural powers of mountains, rivers, lakes, seas, the sun, the moon, stars, wind, rain, thunder, lightening, birds, and beasts, as many as one can enumerate. These deities govern the birth, ageing, sickness, death, events and fortunes of people, who can not predict and control their own destinies because people have been created by the deities. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

In the 7th century A.D., Buddhism was introduced to Tibet on a large scale and Bon lost its dominance in the mid 8th century. Tibetan Buddihism has been ramified into four major sects: Nyingma Sect, Kadam Sect, Sakya Sect, Kagyu Sect and Gulug. These sects have had significant and extensive impacts on the political, economic and cultural life of Tibet and its progression through different period of time. Buddha is the sovereign of the realm of Tibetan Buddhism, and is the most frequently occurred figure in Tibetan art works as well. The major subject matters of Tibetan arts include Buddha, Bodhisattvas and a Variety of Deities, the mandala, the Gurus and Dharma Kings, the biographic Stories and Jataka Stories of Sakyamuni.

Night Out a Langma Hall in Lhasa

Xinhua reported in 2011: The word "Langma" in Tibetan language means courtly performance, which in the past was only an entertainment for Tibetan traditional aristocracy...The present langma hall evolved into a place of part bar, part folk concert hall and part ballroom, where common Tibetan people go for relaxation and gathering. Since the first such place opened in the mid-1990s, Langma halls soon became quite popular all over Tibet and emerged one after another in a short time. [Source: Xinhua, May 10, 2011]

Today, Niwei is one of the biggest Langma halls in Lhasa. Its owner Gyaebo, who used to be a famous tap dancer in Lhasa, runs four langma halls of his own. All of his langma halls perform traditional Tibetan songs and dances, but in order to cater to different taste of customers, two langma halls emphasize on modern, western dance and even disco, while the others focus on Tibetan "guozhuang" and tap dance.

Twenty-year-old Rinzin Dawa, a graduate from Chengdu Normal University in southwest China's Sichuan Province, started working in Niwei Langma Hall after quitting an insurance company about a year ago. "I really like music and dancing, it is great to work here. I am happy everyday." Rinzin said. After learning and performing in langma hall for one year, he has mastered a dozen of traditional Tibetan dances. Nevertheless, he was even more delighted to have the chance to perform dances in neighboring regions of Lhasa, such as Quxu, Dagaz and Zhanang County, listening acclamations of local villagers.

“As the clock finger pointed to eleven, Niwei Langma Hall was almost full of audiences. Ordering several canned beer, chatting with friends, dancing "guozhuang" dance ("singing and dancing in a circle") on the stage with others, local guests are appealed here to enjoy Lhasa's most exciting night life, while curious tourists come to have a sip of the original Tibetan culture. Ngawang, a Tibetan born in 1970's, who works for a construction company in Lhasa, is one of the frequent customers of langma hall. "This is my favorite entertainment, it offers genuine Tibetan music, dances and drinks," he made a toast to his friend Zhamdu and continued, "I come here at least once a week. It's almost a must for me".

At two o'clock in the morning, strong rhythms of Tibetan music and "guozhuang" dances continued to jolt the Langma hall. The sound of joy would not fade away until 4 to 5 o' clock. However, in less than two hours, the nearby Barkhor Street will greet the first batch of pious pilgrims, awakening the city again.

China’s Effort to Collect and Bring Culture to and from Tibet

According to the Chinese government: As early as the 1950s, a group of literary and art workers from different ethnic groups went to Tibet to collect music, dance, folk stories, proverbs and folk songs with their Tibetan counterparts, and edited them for publication. One fruit of their labors was the book, "Tibetan Folk Songs." Beginning at the end of the 1970s, the state conducted a large-scale systematic survey, collection and edition of Tibetan folk cultural and art heritage. Since the 1980s, a group of region-, prefecture- and city-level institutions have been set up to save, collect, research, edit and publish Tibetan folk literary and art heritage. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China, October 26, 2005]

These efforts have resulted in the collection of about 30 million words of written materials in the Han Chinese and Tibetan languages, the making of a large amount of videotapes and the taking of nearly 10,000 pictures. On this basis, the History of Chinese Operas and Story-telling Ballads: Tibet Volume, Collection of Chinese Folk Songs: Tibet Volume, Collection of Folk Dances of Chinese Ethnic Groups: Tibet Volume, and Collection of Chinese Proverbs: Tibet Volume have been published, and a series of collections of Tibetan ballads, folk songs, opera music and folk stories are now under compilation and will be published very soon.

The world-famous "Life ofKing Gesar," a lengthy and valuable heroic epic created by the Tibetan people over a considerable length of time, is a rare literary treasure of China and the whole of mankind. However, it has only been passed down orally by folk artists. To better protect it, the regional authorities set up special bodies in 1979 for the collection, research, editing and publishing of the tome. The state placed it on the key scientific research project lists of the Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Five-Year Plans. After 20 years of effort, nearly 300 handwritten or block-printed Tibetan volumes have been collected. Among them, except 100 variant volumes, about 70 volumes have been formally published in the Tibetan language, with a total print run of well more than 3 million copies.

As of 2005, Tibet had constructed more than 400 mass art centers, where rich recreational and sports activities of diverse forms can be carried out. The Tibet Library was opened in July 1996, and has been visited by over 100,000 Tibetan readers by 2005.. At that time Tibet had 17 mobile performance teams and some 160 amateur theatrical performance teams and Tibetan opera teams at the county level. These teams always perform for the people of the farming and pastoral areas, and are very popular there.

Lhozhag County, Biru County, Chenggo Township in Gonggar County, Jiongriwuqi Township in Ngamring County and Gyangze County, are famous for their Tibetan opera, song and dance performances, folk plastic art, folk dances, Tibetan opera and Tibetan carpets respectively. From 1995 to 1999, 40 professional and amateur art ensembles made up of 360 people were sent by the Tibet Autonomous Region to perform or hold exhibitions in or conduct academic exchanges with more than 20 countries and regions worldwide, and wherever they went, they were enthusiastically welcomed.

Amassing Tibetan Texts Saved from the Cultural Revolution

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “Decades ago, the thousands of Tibetan-language books now ensconced in a lavishly decorated library in southwest China might have ended up in a raging bonfire. During the tumultuous decade of the Cultural Revolution, which ended in 1976, Red Guard zealots destroyed anything deemed “feudal.” But an American scholar, galvanized in part by those rampages, embarked on a mission to collect and preserve the remnants of Tibetan culture. The resulting trove of 12,000 works, many gathered from Tibetan refugees, recently ended a decades-long odyssey that brought them to a new library on the campus of the Southwest University for Nationalities here in Chengdu. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, February 15, 2014 ^/^]

“Despite Beijing’s tight control of Tibetan scholarship, the collection’s donor, E. Gene Smith, insisted that the books be shipped here from their temporary home in New York, because as he told friends, “they came from Asia, and Asia is where they belong.” Just to be safe, he created a backup digital copy of every text. Mr. Smith, a lapsed Mormon from Utah who spoke 32 languages and died in 2010, spent much of his life working for the Library of Congress. His interest in Tibetan literature was aroused by an encounter with a Buddhist lama, Deshung Rinpoche. After converting to Buddhism, Mr. Smith found his studies stymied by the paucity of Tibetan texts. He moved to India and began a 25-year quest to find Tibetan books, many of them smuggled out by refugees who had trekked over the Himalayas. ^/^

Using money from an American government program, he printed thousands of rare texts that were later distributed to libraries and scholars around the world. Mr. Smith invariably kept one copy of each print run, forming a collection that took over his Cambridge home and eventually filled two trailers. In 2007, to the dismay of several American universities that coveted the books, Mr. Smith bequeathed his collection to the Southwest University for Nationalities. But a few months later, after deadly ethnic rioting in Lhasa, university officials suspended the project. Officials eventually opened the center, creating the nation’s pre-eminent center for Tibetan literature. But they appear to be reluctant to promote it. During a recent visit, Tibetan students complained that the doors of the library were often locked, but they were thrilled about its existence.“This is our culture; this is our heritage,” Puchor, a student who like many Tibetans uses only one name, said after touring the library. “We need to learn about our patrimony and then protect it for future generations.” ^/^

“As news of the center’s existence has spread across China, the keepers of centuries-old books have flocked to the library with manuscripts that scholars thought had been lost or destroyed. Many had been hidden by Tibetan monks during the Cultural Revolution, when Buddhist monasteries, religious statues and sacred texts were systematically destroyed. In November 2013, robed monks from the Dongkar Monastery in western Sichuan arrived with a yellowing collection of 300-year-old texts that had never been published. Scrawled in cinnabar and black ink, the manuscripts, detailing the tantric rituals of Buddhist deities, were copies of 15th-century texts. The monks stayed for five weeks while archivists scanned 6,000 pages, then returned home carrying their beloved texts and a single CD-ROM of digital copies. They vowed to return with seven more volumes.” ^/^

Image Sources: Purdue University, Cosmic Harmony, the film Kundun

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022