TIBETAN ART

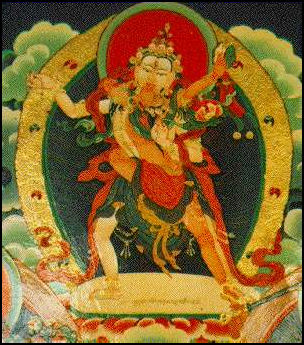

Tantric thangka Much of Tibetan art is oriented towards Buddha, gods and merit. Many works have complex iconography and symbolism that requires extensive knowledge about Tibetan Buddhism to unravel. Influences come from the Pala kingdom in India, the Newari kingdom in Nepal, Kashmir in India, Khotan in Xinjiang, and China.

The major art forms are: 1) Tibetan paintings, including thangkas (cloth paintings), frescoes, mandalas, rock drawing and contemporary painting; 2) Tibetan sculptures, including Buddhist sculptures, metal sculptures, clay modelings and stone carvings; 3) Tibetan handicrafts, including metal wares, masks, block-printing, textiles handicrafts and wooden wares; and 4) Tibetan architectures including ancient tomb architecture, monastery architecture, palace architecture and residence architectures;

Most Tibetan art has traditionally been produced by monks at monasteries. Most artists were anonymous and rarely signed their works, although names have survived in texts, in murals on monastery walls, and on some thankas and bronzes. Mark Stevenson, a lecturer on Asian art at Melbourne University told the New York Times, “Every monk has a need for artistic talent. They make alms and assemble tormas, which are offering cakes. Many have to work on mandalas as well. This is part of being a monk. Every monk needs some manual dexterity skill in designing ritual objects.”

Much of Tibet’s great art was either destroyed by Communists, particularly in the Cultural Revolution, or taken out of Tibet and sold in art shops and auctions and now is in the hands of collectors. Tibetan are is increasingly being sought after by collectors. Art auctions sponsored by Christie’s and Sotheby’s often feature art that was looted or was confiscated during the Cultural Revolution.

The most well-known contemporary Tibetan artist is Kalsang Lodrie Oshoe.

articles on TIBETAN CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; See Separate Articles TIBETAN ART factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN PAINTING factsanddetails.com; THANGKAS: TYPES, SUBJECTS, MATERIALS AND MAKING THEM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN ARCHITECTURE: TEMPLES, PALACES, STUPAS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Himalayan Art Resources himalayanart.org ; Buddha.net buddhanet.net ; Conserving Tibetan Art and Architecture asianart.com ; Guardians of the Sacred World (Tibetan Manuscript Covers) asianart.com ; Wikipedia article on Mandalas Wikipedia ; Introduction to Mandalas kalachakranet.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet” by M.M. Rhie and Robert Thurman Amazon.com . “Images of Enlightenment: Tibetan Art in Practice” by Jonathan Landaw and Andy Weber Amazon.com; “Tibetan Art” by Lokesh Chandra Amazon.com; “Buddhist Art of Tibet: In Milarepa's Footsteps: by Etienne Bock, Jean-Marc Falcombello, et al. Amazon.com; “Art of Tibet” by Robert E. Fisher Amazon.com; “Tabo: A Lamp for the Kingdom : Early Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Art in the Western Himalaya” by Deborah E. Klimburg-Salter Amazon.com; Symbols and Iconography: “The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “Buddhist Symbols in Tibetan Culture : An Investigation of the Nine Best-Known Groups of Symbols” by Dagyab Rinpoche and Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; “The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Other Deities: A Unique Pantheon by Lokash Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce Amazon.com; “The Way of the Bodhisattva: Shambhala” by Shantideva, Padmakara Translation Group, et al. Amazon.com; Gods, Goddesses & Religious Symbols of Hinduism, Buddhism & Tantrism [Including Tibetan Deities]by Trilok Chandra Majupuria and Rohit Kumar Amazon.com; Crafts: Buddhist Ritual Art of Tibet: A Handbook on Ceremonial Objects and Ritual Furnishings in the Tibetan Temple Amazon.com; “Tibetan Silver, Gold and Bronze Objects and the Aesthetics of Animals in the Era before Empire: Cross-cultural reverberations on the Tibetan Plateau” by John Vincent Bellezza Amazon.com; “Dream Weavers: Textile Art from the Tibetan Plateau” by Thomas Cole Amazon.com

Tibetan Buddhist Art

Tibetan lamaseries contain thousands of frescoes and statues of Buddha and Buddhist gods such as the eleven-headed Avalokitesvara, the Buddhist god mercy. Many of the frescoes depict episodes from Buddha's life, whose aim in part is to educate the illiterate the same way painting of Christ and the saints in European Christian churches aims to do.

Kathryn Selig Brown wrote in the Metropolitan Museum of Art website: Although Tibet's vast geographic area and its many adjacent neighbors—India and Kashmir, Nepal, the northern regions of Burma (Myanmar), China, and Central Asia (Khotan)—are reflected in the rich stylistic diversity of Tibetan Buddhist art, during the late eleventh and early twelfth century, Pala India became the main source of artistic influence. In the thirteenth century and thereafter, Nepalese artists were also commissioned to paint thankas and make sculptures for Tibetan patrons. By the fourteenth century, stylistic influences from Nepal and China became dominant and in the fifteenth century these fused into a truly Tibetan synthesis. [Source: Kathryn Selig Brown, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art ]

“Although numerous monks were artists, there were also lay artists who traveled from monastery to monastery and, with a few exceptions, it is difficult to assign a particular style to a monastery or sect. Most artists were anonymous and rarely signed their works, although names have survived in texts, in murals on monastery walls, and on some thankas and bronzes. In addition to Tibetan artists, the names of Indian, Nepalese, Central Asian, and Chinese artists were recorded.

Kathryn Selig Brown wrote in the Metropolitan Museum of Art website: “Many sculptures and paintings were made as aids for Buddhist meditation. The physical image became a base to support or encourage the presence of the divinity portrayed in the mind of the worshipper. Images were also commissioned for any number of reasons, including celebrating a birth, commemorating a death, and encouraging wealth, good health, or longevity. Buddhists believe that commissioning an image brings merit for the donor as well as to all conscious beings. Images in temples and in household shrines also remind lay people that they too can achieve enlightenment.” [Source: Kathryn Selig Brown, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art]

History of Tibetan Buddhist Art

According to the Asia Society Museum: “Although Buddhism had been introduced to Tibet by the seventh century, the greatest influx of teachers, texts, and images began in the tenth century. This wave came from India's northeastern regions, then ruled by the Pala dynasty, where Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism were practiced; it was these two types of Buddhism that were adopted in Tibet. The strong links between Pala-period India and Tibet are demonstrated by an important illustrated Buddhist manuscript that has inscriptions in Sanskrit and Tibetan, which trace the manuscript's history from its creation at the famous Nalanda monastery in eastern India, circa 1073, through its use by a number of famous Tibetans over the next 300 years. It was through illustrated manuscripts such as this that both Buddhism and Buddhist art were transmitted from India to Tibet. This stream of Indian influence lasted through the late twelfth and the thirteenth centuries, when Buddhism was annihilated in India, primarily due to Muslim invasions, and many Buddhist monks fled to neighboring countries such as Nepal and Tibet. [Source: Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org |~| ]

“By the fourteenth century, Tibetan artists had synthesized a unique style from Indian, Nepalese, Chinese, and indigenous sources; however, eleventh- and twelfth-century Tibetan artists often tried to replicate Indian prototypes exactly, which sometimes makes it difficult, even for experts, to distinguish between Pala Indian and early Tibetan art. However, Tibet also turned west to Kashmir, a prestigious center of Buddhist learning that produced a number of important scholars and translators over the centuries. It was to Kashmir, for example, that a seventh-century Tibetan king sent envoys in search of a script that would serve the Tibetan language. In 988, a king of western Tibet, Yeshe O, gave royal support for the creation of local workshops to produce images for temples, workshops that likely employed artists from Kashmir. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, Western Tibetan and Kashmiri interactions were so pronounced that until recently a Western Tibetan image of a bodhisattva was thought to have been made in Kashmir.” |~|

Subjects in Tibetan Buddhist Art

Sacred beings that appear regularly in Tibetan Buddhist art can be categorized into five groups: buddhas, bodhisattvas, dharma protectors, great masters, and arhats. Be they peaceful deities or wrathful ones, dharma protectors are the manifestation of skillful means to lead sentient beings to enlightenment. In illustrated sutras dharma protectors account for roughly half the images and female deities a quarter. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

In Buddhism, an arhat is one who achieved Nirvana and often refers to one of the 18 disciples of the Buddha. Arhats are frequent subjects if Tibetan Buddhist art. On a painting in a Tibetan Buddhist texts called T”he First Arhat A gada”, by Yao Wenhan in Qing dynasty, the National Palace Museum says: On the gorgeous Mt. Kailash lived Arhat A gada, holding an incense burner and a scented fly whisk, with other 1,300 arhat attendants accompanying him. Arhat A gada ranks first among the sixteen Tibetan arhats. By the order of Buddha Śākyamuni, he lived on a snowy mountain. In the painting, his head is covered by a halo. He wears the Han-style loose robe, tilting his body on a stone seat. His left arm folds a scented fly whisk, and two hands hold an incense burner. It is said that when the followers smell the incense, they can obtain the fragrant sweetness of precept observation; when they touch the scented fly whisk, they can eliminate affliction and illness. There are monks waiting on both sides of the Arhat. Two lions crawl under his feet. In the halo is the Nāgarāja Buddha with eight snakes spiraling behind the bun of the Buddha's crown. The Nāgarāja Buddha, the objects that Arhat A gada holds, and the monk's upturning robe are all rendered in the Tibetan painting style. (Department of Painting and Calligraphy)

Purpose of Tibetan Religious Art

Tibetan frescoe, 1000 Buddhas In Tibetan art the emphasis is placed on the "sacred process" and devotional aspects of the work rather than the aesthetic qualities and originality of the finished product as is often the case with Western art. Most works are done anonymously. Personal expression and the selling of Tibetan art is frowned upon.

Tibetan art is expected to be a tool for enlightenment rather an expression of the self. John Listopadm an expert on Tibetan art told the Los Angeles Times, "Tibetan art is psychological art and meditational. It is an art which works on people and their personalities. It can calm you down and help you find peace and balance."

Many works of Tibetan Buddhist art are connected with Tantric rituals and are regarded as tools for mediation and worship. Some art objects can he touched, owned, held and moved. Others are meant to be meditated on. These incorporate a “Circle of Bliss,” a sharing of power between the observer and the work of art.

Violence, Politics and Compassion in Tibetan Buddhist Art

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: There is no denying “the transcendent beauty in many of the pieces of” Tibetan Buddhist art and “they can be viewed purely on their merits as vivid expressions of fury, violence, peace, and splendor. But understanding their place in Tibet’s history enhances a deeper appreciation of this still-remote corner of the world and its remarkable journey over the past millennium. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, July 13, 2019]

Karl Debreczeny, a curator at the Rubin Museum in Boston, challenges the western romantic notion of Buddhism and Tibet. He said. Tibetan “rulers were not interested in mindfulness, meditation, and yoga mats; they wanted to know what this religion could do for the state..” These ideas owe a great deal to the influence of Elliot Sperling, the venerated Tibetologist... Sperling’s classic 2001 essay “‘Orientalism’ and Aspects of Violence in the Tibetan Tradition” underpins many of the concepts” in regard to “realism about Tibetan politics and the integration of Buddhism with the needs of secular power.

Vidya Dehejia, a professor at Columbia University, wrote: “ Himalayan Buddhism, especially that of Tibet, introduced some unique imagery. Ferocious deities are protectors of the Buddhist faith and devout Buddhist believers. Esoteric male-female figures in embrace are known as Yab-Yum, or "Father-Mother." They represent the union of wisdom (female) and compassion (male), which results in supreme wisdom leading to salvation. Also popular in the medium of painting are mandalas intended for meditation; these esoteric diagrams of the cosmos center around a deity upon whom the devotee has chosen to meditate. [Source: Vidya Dehejia, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Tibetan Painting

Most Tibetan painting is in the form of murals and frescoes painted on monastery walls. They depict bodhisattvas, scenes from the life of Buddha, Tibetan gods, portraits of famous lamas, “asparas” (angels) and demonlike “dharmpalas” stomping on human bodies. Many are intended to be used as meditation aids.

Tibetan painting has been influenced by art from China, Central Asia and Nepal but is regarded as closest to the original Buddhist art that evolved in India but is now all but lost. The composition of paintings is often the same: a central image of Buddha, surrounded by smaller, lesser deities. Above the central figure is a supreme Buddha from which the central figure emanated.

Some of the best frescoes are seen outside of Tibet in places like Mustang in Nepal and Ladakh in India. Many frescoes in Tibet were either lost or badly damaged in the Cultural Revolution.

TIBETAN PAINTING factsanddetails.com

Thangkas

Thangkas are traditional Tibetan painted tapestries or cloth scrolls designed as aids in meditation. Painted on cotton or linen, they usually contain images of deities and religious figures and often are representations of spiritual or historical events. As is true with mandalas both making a thangka and gazing at one are regarded as forms of meditation. The idea is to lose oneself in thangka not express it. Traditionally, they were never bought or sold. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 29, 2009]

The content of thangkas varies quite a bit. They usually contain portraits of bodhisattvas, giant mandalas, and images of Buddhas. They often depict Tibetan gods and other religious iconography such gods like Padmasambhava and White Tara and Green Tara, and the circle of life with people reclining in heaven and roasting in hell.

Unlike an oil painting or acrylic painting, the thankga is not a flat creation, but consists of a painted or embroidered picture panel, over which a textile is mounted, and then over which is laid a cover, usually cotton, but sometimes silk or linen. Generally, thankgas last a very long time and retain much of their lustre, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places so as to prevent the quality of the silk from being affected by moisture. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

See Separate Article TIBETAN THANGKAS factsanddetails.com

Mandalas

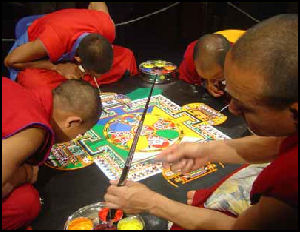

Making a mandala

A mandala is a form of Buddhist prayer and art that is usually associated with a particular Buddha and his ascension to enlightenment. Regarded as a powerful center of psychic energy, it symbolizes the macrocosm of the universe, the miniature universe of the practitioner and the platform on which the Buddha addresses his followers. The design for the mandala is said to have been brought to Tibet by the legendary 1,000-year-old lama, Guru Rinpoche, in the Each Ox Year of 749.

A typical mandala measures five feet across and contains a pictorial diagram of Buddhist deities in circular concentric geometric shapes. Many are shaped like a lotus flower with a round center and eight pedals, with a central deity surrounded by four to eight other deities who are manifestations of the central figure. The deities are often accompanied by consorts. In large mandalas there may several dozen circles of deities, with hundreds of deities.

Mandalas can be painted, constructed of stone, embroidered, sculptured or even serve as the layout plan for entire monasteries.. Most are painstakingly made from sand, preferably sand made from millions of grains of crushed, vegetable-died marble. The tradition of making mandalas is said to be derived from ancient folk religions and Hinduism. Today mandalas are mostly made by followers of Tantric Buddhism.

See Separate Article TIBETAN MANDALAS factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Sculpture

Sculpture, like painting, is mostly religious in nature. Most of images are of Buddha or Buddhist deities. Many are hollow and have Buddhist sutras or prayers inside. Metal sculptures are made using the lost wax technique. Many Tibetan sculptures are of historical figures or real life religious figures such as past Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In Tibetan Buddhism, the esoteric Tantric vehicle was especially emphasized. Distinctive to their sculptures are double bodies or wrathful expressions. The style was influenced by the Kashmiri manner before the 14th century, the Pâla style from eastern India during the 8th to 12th centuries, as well as Nepali, Khotan, and Tun-huang regional styles. After the 15th century, Chinese art also exerted an influence on Buddhist art. Due to the dexterity of craftsmen and completeness of scriptures, the 14th through 18th century was the liveliest period for Tibetan Buddhism. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

See Separate Article TIBETAN SCULPTURE factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Crafts and Objects de Art

Tibetan traditional arts focused on religious worship and included many crafts involved in making religious texts, scriptures, scroll paintings of deities, carved altars, sculpture, altar implements, statues of precious metal inlaid with gems, appliquéd temple hangings, operatic costumes for religious performances, monastic furniture, ritual textiles, and gilt copper figures of animals and gods. Even cairns on pilgrimage trails have been made into works of art. Most of these crafts were made d out by monks in monasteries.

Meanwhile, local peasants produced utilitarian household objects for their own use or purchased them at a local market Tibetan handicrafts and art objects more secular in nature include jewelry, clothing, personal affects, seat covers, bed covers, saddle blankets, daggers, and tents.

Among the Tibetan crafting techniques are encasing, inlaying, and making wire drawing. The techniques used decorate jewelry are also used on religious articles and everyday objects such as snuff bottles with hollowed-out designs; prayer wheels; barrels to hold rice for offering before Buddha images; and sea-snail-shaped ritual horns. The designs are mostly derive from religious beliefs and the lifestyle of the Tibetan people, often featuring symbols that convey special meaning. and the deeply-hued Tibetan silver is a mysterious temptation.

See Separate Articles TIBETAN CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN JEWELRY, ORNAMENTS AND OBJECTS DE ART factsanddetails.com

Nomadic Art of Tibet

The Mongolian, Tibetan, and western Muslim people living in western, southern and northern China and the Eurasian continent share many things in common, including and high terrain and the cold climate, with unpredictable rainfall, in which they live, and the traditional nomadic lifestyle. Except for settlements along river valleys and oases, a nomadic economy has traditionally governed the way of life there. This lifestyle also explains why people living over such a vast area share commonalities in their material culture and art forms. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Nomadism is a lifestyle chosen in response to the natural conditions of the place where they live and usually involving the optimal use of limited resources. Following the customs and experiences they inherited, nomads move with their animals in keeping with the seasons. Livestock, such as horses, cattle, and sheep, is important to them, providing clothing, food, and transportation. Every part of the plants they encounter along the way is also utilized to make many of the things needed in life. These people often live in tent-like structures easy to erect and take apart, as vessels for food and drink are taken with them and not much else. Such basic necessities of life as wooden bowls and utensils, when given as presents, reflect their simple and practical values. The workmanship involved in such objects, however, is elegantly refined, amply demonstrating the maturity of arts and crafts among these nomads.

“Wood bowl and gilt iron case inlaid with turquoise” is Tibetan work at the National Palace Museum, Taipei, dated to 1786 in the Qing dynasty: According to the museum:Wood bowls are the utensils that best illustrate the Mongolian and Tibetan eating habits and can be used to drink tea, hold tsampa, and store food. In addition, wood bowls are light, durable, easy to carry and can be used to preserve the taste of food as well as prevent the heat of the food from burning the hands. Wood bowls are generally made from birches, Rhododendron roots, or roots from a variety of trees; however, the most precious wood bowls are made from parasitic plants (especially a type of tumor called "zan" that is parasitic in mugwort roots). Since the time of the Kangxi era, Tibetan people had often offered wood bowls in early spring as tributes to the Qing court and to wish them a prosperous new year. The Qing court commonly used wood bowls to drink milk tea, earning the container the name "milk bowl." The practice of using the container to drink milk continued through the Yongzheng era. According to the Imperial Workshop Archives, Kalon Khangchenné Sonam Gyalpo offered wood bowls to the Qing court. Similarly, the Dalai Lama offered a set of five small and large wood bowls. The wood bowl and gilt iron hollow round case inlaid with turquoise exhibited here features a metal bowl made of delicate, light, and precious materials and displaying distinct and contrasting threadlike patterns, making this artifact set an example of the treasures offered by Tibetan aristocrats to the Qing court.

Tibetan Art Given as Gifts

Art played a role in relations between Tibet and the Imperial Chinese court. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Not only were Tibetan monasteries centers of religion, they also were vital focal points for local administration and the economy. For this reason, the tribute items sent by Tibetan lamas and nobility to the Qing dynasty court were always the finest in terms of quality. They invariably submitted Buddhist religious implements as gifts because of their constant reference to the Qing emperor in Tibetan diplomatic letters as "Manjusri," the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. The Qing emperors likewise paid homage to Tibetan Buddhism, demonstrating the high level of importance attached to its influence and the accompanying esteem that it earned as a result.

“Silver mandala with multicolored khatas” was presented by the Tuguan Hutuktu to the Qing court in the 19th century. According to the museum; The silver mandala with multicolored khatas was presented by Tuguan Hutuktu (1839–1894), the 6th Lama of the Gönlung Jampa Ling Monastery (in Qinghai) who stayed in China's capital city, to Empress Dowager Cixi on her birthday. The mandala symbolizes the Buddhist world; the surface of the mandala was engraved with wave-like text, whereas the center of the mandala contains a four-story square platform. Mount Sumeru, which represents the center of the universe, is found in the axis, whereas Mount Akravada-Parvata is observed covering the circumference of the surface.

Looted Art from Tibet

In October 2004, Souren Melikian wrote in the New York Times, “Perhaps those who buy sculptural fragments broken off Buddhist structures from Afghanistan to Tibet and other Asian countries are beginning to have second thoughts. Watching the sale "Indian & South East Asian Art" at Sotheby's, any observer aware of the background of some of the works must have experienced deep unease. The work on the catalogue's cover, a Tibetan bronze statue of a 14th-century, four-armed seated figure, Shadakshari Avalokiteshvara, was a disturbing sight. Set on a pedestal against a partition, it sat behind the last row of seats arranged for bidders. The Buddhist statue gave the jarring impression of a parody of respect to a culture whose sacred images have been scattered to the winds by invaders during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. [Source: Souren Melikian, New York Times, October 23, 2004 |~|]

“To underline the statue's importance, the catalogue referred readers to M.M. Rhie and Robert Thurman's "Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet (expanded edition)" and noted that "it is one of very few large Tibetan cast-metal temple sculptures of the period to exist outside Tibet." Pious remarks about the image that "embodies the essence of Shadakshari's mantra, OM MANI PADME HUM, (Hail the jewel in the lotus)" concluded the entry. No one raised a hand as the auctioneer called out $600,000 and brought down his gavel, leaving it unsold. Maybe the estimate, $650,000 to $750,000, plus the sale charge, did not help. Maybe there was something else. |~|

“The danger for buyers goes beyond the risk of future lawsuits. Even if none should take place, the opprobrium that is beginning to surround the ownership of works of art illicitly dug up can only intensify, making later resale problematic. At the very least, it reduces their commercial potential. In the worst of cases, it will make the sale of objets d'art without a verifiable past going back 50 or 60 years, well nigh impossible. When the bill is in the area of $200,000 or more, Sotheby's sale appeared to suggest, these fears can have an inhibiting effect. |~|

“At Sotheby's, memories of past destruction also seemed hazy. They did not wreck the chances of a beautiful gilt copper makara in a style typical of the Densatil monastery, that jewel of 15th-century Tibetan architecture. Photographed by an Italian team in the 1930s, the monastery was destroyed in the 1970s in one of the worst atrocities committed against world culture by the Red Guards. The mythical beast sold for $16,800/ |~|

“Was it right or wrong to buy it? Some will argue that it is better for the piece to be silently admired by a collector respectful of Buddhist art than to go on knocking about the market and risking further damage. Others may stay away from a fragment blighted by destructive fury, wherever it was unleashed. This is a moral dilemma to be resolved by each one of us according to our convictions. Cynics will add that at that price the risk involved was minimal. But there were quite a few failures of low-priced works as well as of expensive ones. In a market starved for goods, where some are prepared to pay the earth, this may mean that a new approach to the debris of destroyed monuments and archaeological sites across Asia is looming.

Image Sources: University of Purdue, Kalachakranet.org, CNTO; Mandala images, Univeristy of Liverpool, Harvard Education Review

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022