TIBETAN PAINTING

Most Tibetan painting is in the form of murals and frescoes painted on monastery walls. They depict bodhisattvas, scenes from the life of Buddha, Tibetan gods, portraits of famous lamas, “asparas” (angels) and demonlike “dharmpalas” stomping on human bodies. Many are intended to be used as meditation aids.

Most Tibetan painting is in the form of murals and frescoes painted on monastery walls. They depict bodhisattvas, scenes from the life of Buddha, Tibetan gods, portraits of famous lamas, “asparas” (angels) and demonlike “dharmpalas” stomping on human bodies. Many are intended to be used as meditation aids.

Tibetan painting has been influenced by art from China, Central Asia and Nepal but is regarded as closest to the original Buddhist art that evolved in India but is now all but lost. The composition of paintings is often the same: a central image of Buddha, surrounded by smaller, lesser deities. Above the central figure is a supreme Buddha from which the central figure emanated.

Some of the best frescoes are seen outside of Tibet in places like Mustang in Nepal and Ladakh in India. Many frescoes in Tibet were either lost or badly damaged in the Cultural Revolution.

See Separate Articles TIBETAN ART factsanddetails.com; THANGKAS: TYPES, SUBJECTS, MATERIALS AND MAKING THEM factsanddetails.com; MANDALAS: TYPES, MEANING AND MAKING THEM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN SCULPTURE factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN JEWELRY, MASKS AND OBJECTS DE ART factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN ARCHITECTURE: TEMPLES, PALACES, STUPAS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Painting: “Tibetan Painting” by Hugo Kreijer Amazon.com; “Painting Traditions of the Drigung Kagyu School” by David P. Jackson, Christian Luczanits, et al. Amazon.com; “Mirror of the Buddha: Early Portraits from Tibet” by David P. Jackson Amazon.com; Thangkas: “Tibetan Paintings: A Study of Tibetan Thankas, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries” by Pratapaditya Pal, with lots of illustrations Amazon.com; “Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials” by David Jackson and Janice Jackson Amazon.com; Art: “Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet” by M.M. Rhie and Robert Thurman Amazon.com . “Images of Enlightenment: Tibetan Art in Practice” by Jonathan Landaw and Andy Weber Amazon.com; “Tibetan Art” by Lokesh Chandra Amazon.com; “Buddhist Art of Tibet: In Milarepa's Footsteps: by Etienne Bock, Jean-Marc Falcombello, et al. Amazon.com; “Art of Tibet” by Robert E. Fisher Amazon.com; Symbols and Iconography: “The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Other Deities: A Unique Pantheon by Lokash Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce Amazon.com; “The Way of the Bodhisattva: Shambhala” by Shantideva, Padmakara Translation Group, et al. Amazon.com; Gods, Goddesses & Religious Symbols of Hinduism, Buddhism & Tantrism [Including Tibetan Deities]by Trilok Chandra Majupuria and Rohit Kumar Amazon.com;“The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “Buddhist Symbols in Tibetan Culture : An Investigation of the Nine Best-Known Groups of Symbols” by Dagyab Rinpoche and Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com

Thangkas

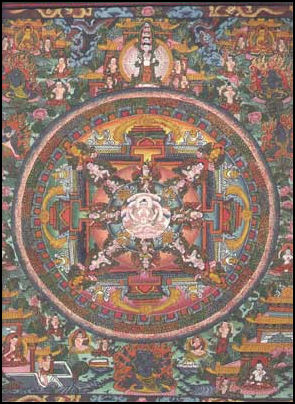

Thangkas are traditional Tibetan painted tapestries or cloth scrolls designed as aids in meditation. Painted on cotton or linen, they usually contain images of deities and religious figures and often are representations of spiritual or historical events. As is true with mandalas both making a thangka and gazing at one are regarded as forms of meditation. The idea is to lose oneself in thangka not express it. Traditionally, they were never bought or sold. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 29, 2009]

The content of thangkas varies quite a bit. They usually contain portraits of bodhisattvas, giant mandalas, and images of Buddhas. They often depict Tibetan gods and other religious iconography such gods like Padmasambhava and White Tara and Green Tara, and the circle of life with people reclining in heaven and roasting in hell.

Unlike an oil painting or acrylic painting, the thankga is not a flat creation, but consists of a painted or embroidered picture panel, over which a textile is mounted, and then over which is laid a cover, usually cotton, but sometimes silk or linen. Generally, thankgas last a very long time and retain much of their lustre, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places so as to prevent the quality of the silk from being affected by moisture. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

See Separate Article TIBETAN THANGKAS factsanddetails.com

Rutog Rock Paintings in Western Tibet

The famous bird-observing site, Pangongcuo Lake, is surrounded by rocks on which there are many paintings. They are the well-known Rutog rock paintings in western Tibet. Some of them are on the rocks beside the road. You can easily see them in your car if you travel to Ngari, west Tibet. But these have been painted relatively recently. You should get off the road to view the ancient rock paintings at Rutog. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

In recent decades, people found a large number of rock paintings in the Gerze, Ge'gyai and Rutog counties. Some of them are found in higher elevations in western and northern Tibet. They consist mainly of deep and shallow lines carved on stones with harder rocks or other hard objects. Some images have been painted in rich colors. The most beautiful rock paintings in about a dozen places in the Rutog County. Among them, those in the Risum Rimodong and Lorinaka are both large in size and great in number. Their artistic value is important but as of is not completely understood and is not even really known how old they are although they are believed to be very ancient.

In ancient times, Tibetan people used the stone inscriptions to describe and record their way of life. The content of the Rutog rock paintings are very rich, including images of hunting, religious rituals, riding, domestic animal herding and farming, and objects like the sun and moon, mountains, yaks, horses, sheep, donkeys, antelopes, houses and human figures.

The capital of the ancient Xiangxiong Kingdom was also in the Ngari. Xiangxiong writing is a special form of writing created by the ancestors of the Tibetan ethnic group. This kind of writing is significant as it appeared before Tibetan writing. Thus, the rock paintings here are very important to study the history, culture and early human life in Ngari, as well as the whole region of Tibet.

Tibetan Mural Painting

Tibetan mural painting traditions grew out Tibet's indigenous religion, Bon, and Tibetan Buddhism but also incorporate features from the religious and artistic traditions of India and Nepal. While the majority of the murals center on religious aspects of Tibetan culture, others portray historical figures or social activities. As many of these murals are religious in nature, murals are concentrated in temples, the holiest sites in Tibet, although they may be seen anywhere. [Source: China Tibetan Information Center, cultural-china.com, Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Tibetan murals contain rich content, involving religion, politics, history, economy, culture, Tibetan medicine, and social life. Any of the Buddhist scriptures, Buddhist messages, fairy tales, history stories, daily living scenes, mountains and rivers, birds and flowers, patterns and adornment can be adopted into a wall painting, which has a unique style. It uses cold and dark colors, such as black, dark blue, mauve, dark grey, brown and white; drawing with lines, especially plain lines; simple, rough and sparse outlines. It has the same style of art as the atmosphere of the monastery, and contains exaggerated and distorted art images.

Brightly colored wall paintings can be found everywhere in Tibetan monasteries. Some of them are more than 1300 years old. As it is recorded in Tibetan history, in the year when Songtsen Gampo, the Tibetan king, inherited the throne, it is said he saw Sakyamuni, Horse-necked Diamond King, Tara, Stationary Vajrapani, and the four Buddhas. He told the Nepali artisan, Ciba, to carve the four Buddhas into a rock wall and paint them. This is the earliest wall painting and sculpture.

History of Tibetan Mural Painting

Some of the earliest Tibetan murals and Buddhist paintings are found in caves and thus it can argued that the art form evolved from early rock paintings. Early rock paintings found in Tibet consisting mainly of the animal images of deer, ox, sheep, horses, and hunting scenes. Rock painting was quite developed in ancient times, especially after Buddhism arrived, and religious painting was further developed. [Source: China Tibetan Information Center, cultural-china.com, Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Tibetan mural experienced two periods. The first period starts after Songtsen Gampo became the king. Because he married a Khridzun princess of Nepal, and a Wenchen princess of the Tang Dynasty who brought Buddhist statues and Buddhist scriptures, he built Jokhang Monastery and Romoche Monastery, which affected the development of wall painting. The figures in the wall paintings of that period are chubby, and painted with simple color, which is close to the art works at Dunhuang by Bei Wei and the beginning of the Tang Dynasty.

The second period started around 10 century A.C. when the initiator of the Yellow sect, Zongkapa, reformed the religion. Yellow sects grew rapidly as the predominant religion. The number of yellow sect monasteries increased to 3000. During that period, the political and religious leaders collected many folk painters to complete wall painting jobs, and let them run in the families. That is the most splendid period of wall painting. The painters gave human life to the statue of Buddha through art, which make the statue look faithful, handsome, merciful, charming, fiery and forthright. Such works exist as picture-story book in all the monasteries. Each of these images has distinct features that can be easily recognized by someone who knows a little bit of Tibetan culture.

Types of Tibetan Murals

1) Religious Murals: Murals in Tibet focus primarily on religion. Although some early murals devoted to Bon still exist, most of the contemporary murals depict various aspects of Buddhism. The most popular murals are of religious figures, such as Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Guardians of Buddhist Doctrines, Taras in the sutras, or Buddhist masters. In these paintings, there is always a head deity or human, who is usually surrounded by some other deities or humans. If the central figure is featured alone, his surroundings are extravagantly detailed. Jokhang Temple and Tashilhunpo Monastery have built special courtyards dedicated to this type of mural painting. [Source: China Tibetan Information Center, cultural-china.com, Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

In addition to the murals of religious figures, there are also some that focus on religious activities, such as debating sutras, Changmo Dance, the Buddhist cosmologic mandalas , and other Buddhist morality tales. In certain temples, chains of pictures illustrate Tibetan legends or follow the lives of religious figures like Sakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism. One of the most famous legends about the Tibetan ancestors - a monkey and a Raksasi - is told in the murals of Potala Palace and Norbulingka.

2) Historical Murals: Based on the history of Tibet, these murals depict key historical figures and events. There are paintings of ancient Tibetan kings, like Songtsen Gampo (617-650), Trisong Detsen (742-798) and Tri Ralpa Chen (866-896) of Tubo Kingdom, as well as their famous concubines, Princess Wencheng and Princess Jincheng of Tang Dynasty (618-907) and Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal. Their stories are told through the series of pictures in Potala, Jokhang and Norbulingka. In Potala, there are also chains of pictures about the biography of the 5th Dalai Lama , who had done much to facilitate the friendship of Tibet and the Chinese central government. Two other historical murals of note: in Ruins of Guge Kingdom there are a series of murals about the rise and down of Tubo Kingdom; and an impressive mural in Norbulingka provides a brief illustration of the entire Tibetan history, from the origination of Tibetans to the 14th Dalai Lama's meeting with Chairman Mao.

3) Social Murals: Some murals are neither religious nor historical, but rather feature the social life of Tibetans. For example, in Jokhang Temple , there is a group of jubilation murals that shows people singing, dancing, playing musical instruments and engaging in sporting matches. In Potala and Samye Monastery , murals of folk sport activities and acrobatics can also be seen.

In addition, many large palaces or temples in Tibet feature murals that describe their entire architectural design and construction process. These murals can be found in Potala, Jokhang, Samye Temple, Sakya Monastery and other famous buildings in Tibet.

Whether religious, historical or social, all of the murals are elaborate and detailed pieces created by expert artists. In some cases, strict guidelines define the correct way that a key figure should be depicted, so the artist must use his artistic talents to impart subtle differences that make the mural unique from others that feature the same figure. Colors must be applied properly to make sure the murals do not fade excessively over time.

Donggar Frescos in Western Tibet

The vast stretches of the Ngari region in western Tibet is the birthplace of the Bon Religion and the home of the capitals of the ancient Xiangxiong and Guge kingdoms. The region is also the home of some of Tibet’s oldest art: the Donggar frescos and Rutog rock paintings. Discovered relatively recently, these 1000-year-old frescoes are among the oldest Buddhist art in Tibet and were produced when the small Guge Kingdom was the main culture center in Tibet. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Donggar, located in Zhada County, is a small village with only a dozen households. It is about 40 kilometers northwest of the ruins of the Guge Kingdom. Many important archeological discoveries have been made. Two grottos—one discovered on the cliff near the Donggar village, and the other near neighboring Piyang Village—are the largest known Buddhist caves in Tibet.

Donggar frescos are housed in three caves. The caves are located half way up the mountain. Since no records are left, much about them remains a cultural mystery. The craftsmanship is of a high quality. They were well knitted with smooth, easy lines, using bright colors and unique designs. The contents include exotic figures, patterns and designs. They are in amazingly good condition: almost a good as those in Mogao Caves in Dunhuang. People think the special mineral-based paints is one of the secrets to their longevity.

Figures of Buddha are the main images of the frescos. There are also images of Bodhisattvas, protectors of Dharma, and men with unnatural strength. The frescos also depict legendary stories about Buddhism. We can also find pictures expounding on Buddhist texts, and pictures of people worshipping Buddha. Other images include various decorations like peacocks, dragon fish, twin dragons, two phoenixes standing opposite each other, and the Tantric Mandala. There are foreign animals in the frescos, like the dragon, phoenix, lion, horse, sheep, cattle, wild goose, duck and elephant. The most common images are apsaras—heavenly girls—a sign of Indian influence.

The universe described in the Donggar frescos is both colorful and figurative. Preliminary investigation indicates different types of cave groups. There are caves for worshipping Buddha, caves for monks and caves for the storage of sundry objects. In the caves for worshipping Buddha we can find the most exquisite and marvelous frescos. In order to protect these precious frescos, public are not allowed to get close to the frescos.

Guge Frescos in Western Tibet

The Guge frescos mainly refer to the frescos in the Red and White palaces of the ruins of Guge Kingdom (900-1630 A.D.), a small but enduring and culturally-important city-state in western Tibet. The Guge frescos include religious subject matter and images of ordinary people ploughing, sowing, harvesting, hunting and milking. Most of the older ones are about 300 years old. The key colours of these frescos are red, orange and yellow, which look especially bright juxtaposed against the black and greenish rocks. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

The aesthetic effect of Guge Frescos is close to that of the much older Mogao cave frescos Dunhuang: sublimity mixed with elegance, symmetry with harmony, femininity with masculinity, melancholy with heroism, and religiosity with romanticism. Compared with Donggar frescos that use direct colour stipples and batik-style painting (disambiguation), Guge frescos present a delicacy of brush strokes and a beauty of black ink framing that is more akin to traditional Chinese painting.

frescoe of feminine spirit

900-Year-Old Tibetan Art at Alchi Monastery in Ladakh

One of the best places to see old Tibetan Buddhist art is a small monastery in Alchi, a hamlet high in the Indian Himalayas along the border with Tibet in the Ladakh region of India. Some works are about 900 years old and they are among the best-preserved examples anywhere of Buddhist art from this period. [Source: Jeremy Kahn, Smithsonian magazine, April 2010]

Jeremy Kahn wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The Alchi murals, their vibrant colors and beautifully rendered forms rivaling medieval European frescoes, have drawn a growing number of tourists from around the world.” In 2008, an Indian photographer, Aditya Arya, arrived in Alchi to begin documenting the monastery’s murals and statues before they disappear. A commercial and advertising photographer best known for shooting “lifestyle” pictures for glossy magazines and corporate reports, he once shot stills for Bollywood film studios. In the early 1990s, he was an official photographer for Russia’s Bolshoi Ballet.

“Although tourists now far outnumber worshipers, Alchi is still a living temple under religious control of the nearby Likir Monastery, currently headed by the Dalai Lama’s younger brother, Tenzin Choegyal. Monks from Likir serve as Alchi’s caretakers, collecting entrance fees and enforcing a prohibition on photography inside the temples. (Arya has special permission.) At the same time, responsibility for preserving Alchi as a historic site rests with the government’s Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Jeremy Kahn wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The monastery and its paintings are in grave danger. Rain and snowmelt have seeped into temple buildings, causing mud streaks to obliterate portions of the murals. Cracks in clay-brick and mud-plaster walls have widened. The most pressing threat, according to engineers and conservators who have assessed the buildings, is a changing climate. The low humidity in this high-altitude desert is one reason Alchi’s murals have survived for almost a millennium. With the onset of warmer weather in the past three decades, their deterioration has accelerated. And the possibility that an earthquake could topple the already fragile structures, located in one of the world’s most seismically active regions, remains ever-present...Conservationists also worry the foot traffic may take a toll on ancient floors, and the water vapor and carbon dioxide the visitors exhale may hasten the paintings’ decay. [Source: Jeremy Kahn, Smithsonian magazine, April 2010]

See Separate Articles: Aichi Monastery LEH factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: University of Purdue, Kalachakranet.org, CNTO; Mandala images, Univeristy of Liverpool, Harvard Education Review

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022