ETHNIC MINORITIES AND THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT

Uyghur girl Minorities make up about nine percent of China’s population. Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: The Chinese “government has supported Han migration to minority territories in an effort to spread the population more evenly across the country and to control the minority groups in those areas, which sometimes are perceived as a threat to national stability. The rise in population among the minorities significantly outpaces that of the Han, as the minority groups were exempt from the government's one-child policy.” [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The impact of Chinese government policy on the lives of ethnic minorities varies from region to region and minority to minority. In most cases the government builds roads, schools and clinics but their quality is often less that than those received by Han Chinese. Minorities are often exempt from China’s strict family planning rules but often their homelands are threatened by encroachment by Han Chinese. Some minorities are in danger of becoming minorities in the areas where they have traditionally been the majority.

Jianli Yang and Lianchao Han wrote in The Hill: “China has been carrying out propaganda that it cares for its minority communities, putting forth this perspective at various international forums, such as the United Nations Human Rights Council and the council’s Universal Periodic Review Working Group, and in white papers issued periodically. In its September 2019 white paper, “Seeking Happiness for People: 70 Years of Progress on Human Rights in China,” Beijing claimed that it has effectively guaranteed ethnic minority rights in administering state affairs, with representation of all 55 ethnic minority groups in the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. [Source: Jianli Yang and Lianchao Han, The Hill, July 29, 2020]

“It also claimed that it fully protects the freedom of ethnic minorities to use and develop their spoken and written languages, and that the state protects by law the legitimate use of spoken and written languages of ethnic minorities in the areas of administration and judiciary, press and publishing, radio, film and television, and culture and education. China claims to have established a database for the endangered languages of ethnic minority groups, and has initiated a program for protecting China’s language resources.

See Separate Articles: ETHNIC MINORITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DIVERSITY, ASSIMILATION AND ETHNIC RELATIONS AND TENSIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PUSHING MANDARIN AND TRYING TO PRESERVE OTHER CHINESE DIALECTS AND LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com; PROBLEMS FACED BY MINORITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Governing China's Multiethnic Frontiers” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com “Affirmative Action in China and the U.S.: A Dialogue on Inequality and Minority Education” by M. Zhou and A. Hill Amazon.com; “China's Minority Cultures: Identities and Integration Since 1912" by Colin Mackerras Amazon.com; “Coming to Terms with the Nation: Ethnic Classification in Modern China” by Thomas S Mullaney and Benedict Anderson Amazon.com; “Social and Economic Stimulating Development Strategies for China’s Ethnic Minority Areas” by Yanzhong Wang , Sai Ding, et al. Amazon.com; Amazon.com; Education and Language: “An Introduction to Ethnic Minority Education in China: Policies and Practices” by Sude, Mei Yuan, et al. Amazon.com ; “Minority Languages, Education and Communities in China” by L. Tsung Amazon.com; “China's National Minority Education: Culture, Schooling, and Development” by Gerard A. Postiglione Amazon.com; “Language, Culture, and Identity among Minority Students in China: The Case of the Hui’by Yuxiang Wang Amazon.com ; “Minority Education in China: Balancing Unity and Diversity in an Era of Critical Pluralism” by James Leibold and Yangbin Chen Amazon.com

Political Importance of Places Minorities Live in China

Many of the places where minorities live — including Tibet and Xinjiang and areas near the borders of Burma, India, Russia, Mongolia and the republics of the former Soviet Union — are regarded as places where discontent and unrest "could threaten security." Many minorities living along China's perimeter live across from the border from people — often of the same ethnic group — that either have their own states or have more freedom than people living in China. The Chinese are concerned about independence movements launched by these minorities and border conflicts with countries such as India, Vietnam or Afghanistan.

“Because many of the minority nationalities are located in politically sensitive frontier areas, they have acquired an importance greater than their numbers. Some groups have common ancestry with peoples in neighboring countries. For example, members of the Shan, Korean, Mongol, Uygur and Kazak, and Yao nationalities are found not only in China but also in Burma, Korea, the Mongolian People's Republic, Kazakhstan and Thailand, respectively. If the central government failed to maintain good relations with these groups, China's border security could be jeopardized. [Source: Library of Congress]

The minority areas are economically as well as politically important. China's leaders have suggested that by the turn of the century the focus of economic development should shift to the northwest. The area is rich in natural resources, with uranium deposits and abundant oil reserves in Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region. Much of China's forestland is located in the border regions of the northeast and southwest, and large numbers of livestock are raised in the arid and semiarid northwest. Also, the vast amount of virgin land in minority areas can be used for resettlement to relieve population pressures in the densely populated regions of the country.

What Constitutes a Minority According to the Chinese Government Policy on Minorities

Lhoba, China's smallest minority

The ethnic groups recognized in China were defined and organized by the Chinese government.The Chinese define a nationality as a group of people of common origin living in a common area, using a common language, and having a sense of group identity in economic and social organization and behavior. Altogether, China has fifteen major linguistic regions generally coinciding with the geographic distribution of the major minority nationalities. [Source: Library of Congress]

In the People's Republic of China there are 56 recognized minzu, meaning “nation," “nationality," ethnic group," or “people." All but the Han are referred to as “shaoshu minzu." “Shaoshu means 'minority'. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ The criteria for identifying these groups are unevenly applied and guided in part by political considerations. Officially, the Chinese government defines a minzu as a population sharing common territory, language, economy, sentiments, and psychology. This definition derives from Stalin's writings on the national question, and it is difficult to apply to the situation in China because of population movements and other events of recent history. The term implies legal equality together with subordination to the higher state authority that governs Han and minorities alike. It is worth noting that the term minzuxue, often translated as “ethnology," refers only to the study of China's minority peoples. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Kelly Olsen of AFP wrote: “China's constitution proclaims that the country's dozens of minority groups are an integral and equal part of the national tapestry, but analysts say a system of ethnic labelling — originally meant to promote minority rights — is fuelling unrest. The country's constitution emphasizes the need "to combat big-ethnic chauvinism, mainly Han chauvinism, and also to combat local-ethnic chauvinism"."The state will do its utmost to promote the common prosperity of all ethnic groups," it says. While ethnic categorisation was meant to foster minority rights and status, in places such as Xinjiang it now serves to harden parochial rather than national identity, analysts say. "They've shot themselves in the foot by having fixed ethnic identification," said Reza Hasmath, an Oxford University lecturer in Chinese politics who studies Uyghur issues. "By virtue of doing that, the party has actually solidified ethnic boundaries." [Source: Kelly Olsen, AFP, July 3, 2013]

Minority Rights and Restrictions in China

All nationalities in China are equal according to the law. Official sources maintain that the state protects their lawful rights and interests and promotes equality, unity, and mutual help among them. Issues involving minorities and ethnic groups are overseen by the Office of Nationality, Religion and Overseas Chinese Affairs. Beijing exerts control through Chinese-language school, whose curriculum has a strong nationalist slant. Success in these schools and learning Chinese are regarded as essential to getting ahead and getting a good job. The local government structures are usually not that different from those in non-minority areas, except that tribal leaders and village elders are incorporated into the system. The state owns the land and leases it out on a contract basis in return for taxes or the handover of a portion of the harvest.

Members of ethnic minorities are required to carry ID cards that have their ethnicity listed on it. Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The state controls population transfers: minority people cannot opt to resettle in the autonomous region of ethnic choice, and the authorities even discourage travel across county boundaries. Most minorities were not affected by the one-child policy, although the government encouraged them to practice family planning. Also, for registration purposes, most minority people must select a Chinese name for their children and follow the Chinese model of the paternal surname. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Aside from these constraints, the minorities are free to use their own languages, follow culturally valued styles of housing, dress, and diet, practice customs that are not in direct violation of national laws, develop and perform their traditional arts, and practice their own religions. During the ten years of the Cultural Revolution, however, holders of or contenders for local power violated these rights, attacking or virtually prohibiting expressions of local culture such as language, dress, food preferences and economic techniques, traditional arts, and religious ritual.

Chinese Government Policy on Minorities

Henzhen, China's second smallest minority

Since 1949 Chinese officials have declared that the minorities are politically equal to the Han majority and in fact should be accorded preferential treatment because of their small numbers and poor economic circumstances. The government has tried to ensure that the minorities are well represented at national conferences and has relaxed certain policies that might have impeded their socioeconomic development. [Source: Library of Congress]

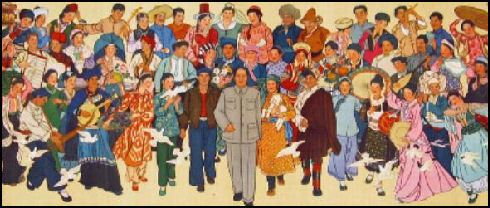

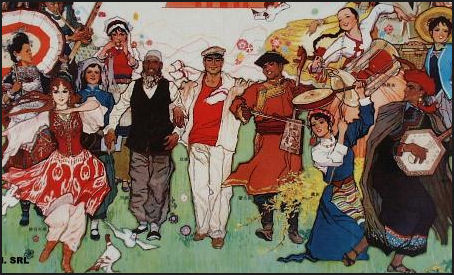

Official policy recognizes the multiethnic nature of the Chinese state, within which all "nationalities" are formally equal. On the one hand, it is not state policy to force the assimilation of minority nationalities, and such nonpolitical expressions of ethnicity as native costumes and folk dances are encouraged. On the other hand, China's government is a highly centralized one that recognizes no legitimate limits to its authority, and minority peoples in far western Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region, for example, are considered Chinese citizens just as much as Han farmers on the outskirts of Beijing are. [Source: Library of Congress]

Official attitudes toward minority peoples are inconsistent, if not contradictory. Since 1949 policies toward minorities have fluctuated between tolerance and coercive attempts to impose Han standards. Tolerant periods have been marked by subsidized material benefits intended to win loyalty, while coercive periods such as the Cultural Revolution have attempted to eradicate "superstition" and to overthrow insufficiently radical or insufficiently nationalistic local leaders.

What has not varied has been the assumption that it is the central government that decides what is best for minority peoples and that national citizenship takes precedence over ethnic identity. In fact, minority nationality is a legal status in China. The government reserves for itself the right to determine whether or not a group is a minority nationality, and the list has been revised several times since the 1950s. Most Han Chinese have no contact with members of minority groups. But in areas such as the Tibet or Xinjiang autonomous regions, where large numbers of Han have settled since the assertion of Chinese central government authority over them in the 1950s, there is clearly some ethnic tension. The tension stems from Han dominance over such previously independent or semi-autonomous peoples as the Tibetans and Uygurs, from Cultural Revolution attacks on religious observances, and from Han disdain for and lack of sensitivity to minority cultures. In the autonomous areas the ethnic groups appear to lead largely separate lives.

China defends its treatment of minorities, saying all ethnic groups are treated equally and that tens of billions of dollars in investment and aid have dramatically raised their living standards. William Wan wrote in the Washington Post, “Nationwide, China has long offered ethnic minority groups favorable treatment as a way to try to integrate them into society, a policy that is often criticized by Han and ethnic minorities alike. When one or both spouses are of ethnic minority, a couple can generally have up to three children, despite China’s one-child policy. Ethnic students are given extra scores for their minority status in college entrance exams. Intermarried families are also often awarded honors for being “models of ethnic unity” and are sometimes favored for government positions. [Source: William Wan, Washington Post, August 18, 2014]

Autonomous Regions, Townships and Counties in China

Many minorities reside primarily in autonomous areas set up for them by the Chinese government. The groups are usually allowed to practice their religion, marriage customs and other aspects of their culture as they please and have some degree of control over their own affairs as long as they respect Beijing’s ultimate authority. “Autonomous” regions have been set for up dozens of ethnic groups but many members of those groups complain that policy is aimed at merely giving the appearance of autonomy while Chinese control remains tight.

Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ Since 1949, a number of areas have been designated as autonomous regions wherein the minorities are guaranteed, within limits, the rights to express and develop their local cultures and representation in the political arena. There are five large autonomous regions (Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Zhuang, Ningxia Hui, Xinjiang Uyghur), each named after the predominant minority group. These regions contain multiple nationalities, the Han now being the largest group in all but Tibet. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

“In addition, by 1985 there were thirty autonomous prefectures and seventy-two autonomous counties, or 'banners," often of mixed ethnicity and sometimes listing two or three minority groups in their official name. Under continuing pressure to grant minorities greater autonomy and representation, the government organized minzuxiang (minority townships) in the 1980s for areas of mixed settlement outside of the larger autonomous units. These townships incorporate Han and minority villages under one administration at the lowest level of government.

Minority Participation in the Chinese Government

Although the minorities accounted for only about 7 percent of China's population in the mid 1980s, the minority deputies to the National People's Congress made up 13.5 percent of all representatives to the congress in 1985, and 5 of the 22 vice chairmen of its Standing Committee (23 percent) in 1983 were minority nationals. A Mongol, Ulanhu, was elected vice president of China in June 1983. Nevertheless, political administration of the minority areas was the same as that in Han regions, and the minority nationalities were subject to the dictates of the Chinese Communist Party. Despite the avowed desire to integrate the minorities into the political mainstream, the party was not willing to share key decision-making powers with the ethnic minorities. As of the late 1970s, the minority nationality cadres accounted for only 3 to 5 percent of all cadres. [Source: Library of Congress]

Ethnic minorities, including Tibetans and Muslim Uyghurs, made up about 6 percent of the Communist Party's 86 million members in the mid 2000s. They are recruited to fill posts at various levels as a key component of the party's united front policy, although the top party official in provinces and regions such as Tibet is always a member of China's overwhelming majority Han ethnic group. [Source: Louise Watt, Associated Press, January 28, 2015]

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Minority representatives are guaranteed seats at various administrative levels from the township up through the county and prefecture, and there are reserved seats for minority representatives in the provincial and national peoples' congresses. The State Nationalities Affairs Commission, directly under the State Council, also includes minority representatives, as do provincial and prefectural branches. Within the autonomous units the state sets some policies. For example, the government has prohibited landlordism, slavery, child marriages, forced marriages, elaborate festivals, and what the state regards as harmful facets of religion and traditional medicine everywhere in China since the early days of the Revolution. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Forging a Chinese Identity Among Chinese Minorities

Steven Denney and Christopher Green wrote in The Diplomat: The Communist Party (CCP) has shown very little practical interest in the preservation of ethnic minority cultures and devoted a great deal of attention to forging some kind of “unified” Chinese identity, In its early years, the CCP took up a carbon copy of the Soviet Union model for governing the multitude of ethnic minorities that fell under its control, and in the 1850s when ethnic autonomous rule formally arrived in many minority areas, relative administrative autonomy and an acceptance of dual national-ethnic identities followed. One could identify as an ethnic “other” (i.e., not Han) whilst remaining nationally Chinese; indeed, an inclusive embrace of diversity was desired. [Source: Steven Denney and Christopher Green, The Diplomat, June 9, 2016]

“For China’s 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities (in addition to the Han majority) there was nothing unduly appealing about being Chinese in those days. States that fail — as the People’s Republic repeatedly did — to deliver basic public goods or a stable political and economic environment do not tend to readily generate loyalty and enduring feelings of patriotism and national pride. As a consequence, many Chinese minorities who came of age in the turbulent years of the 1960s and ’70s are said to hold ambivalent or even anti-CCP attitudes.

“But the young tell a different story. Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening” marked the beginning of the end of China’s era of economic uncertainty. Events at Tiananmen Square in June 1989 were a tremendous shock to the system. The government was in no mood to let a surfeit of independent spirit get in the way of the country’s trajectory, and this — coupled with the disintegration of the Soviet Union — necessitated a recalibration of national policy toward ethnic minority education. The impact was readily felt. In 1990 there were 1,106 Korean elementary schools in the Yanbian autonomous region, but this was down to just 138 by 1999 and 31 another decade after that. In the same period, 155 middle schools withered to 49 in 1999 and 27 in 2009, and 25 high schools shrank back to 19 in 1999 and then lost a further six in the following ten years.

Early History of Ethnic Policy in China

Dru C. Gladney wrote in the Wall Street Journal: "Sun Yat-Sen, leader of the republican movement that toppled the last imperial dynasty of China (the Qing) in 1911, promoted the idea that there were Five Peoples of China — the majority Han being one and the others being the Manchus, Mongolian, Tibetan and Hui (a term that included all Muslims in China, now divided into Uighurs, Kazakhs, Hui etc.). Sun was a Cantonese, educated in Hawaii, who wanted both to unite the Han and to mobilize them and all other non-Manchu groups in China (including Mongols, Tibetans and Muslims) into a modern, multi-ethnic nationalist movement against the Manchu Qing state and foreign imperialists. This expanded policy with the recognition of a total 55 official minority nationalities, also helped the Communists’ long-term goal of forging a united Chinese nation." [Source: By Dru C. Gladney, Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2009, Dru Gladney is president of the Pacific Basin Institute at Pomona College]

Since 1949 government policy toward minorities has been based on the somewhat contradictory goals of national unity and the protection of minority equality and identity. The state constitution of 1954 declared the country to be a "unified, multinational state" and prohibited "discrimination against or oppression of any nationality and acts which undermine the unity of the nationalities." All nationalities were granted equal rights and duties. Policy toward the ethnic minorities in the 1950s was based on the assumption that they could and should be integrated into the Han polity by gradual assimilation, while permitted initially to retain their own cultural identity and to enjoy a modicum of selfrule . Accordingly, autonomous regions were established in which minority languages were recognized, special efforts were mandated to recruit a certain percentage of minority cadres, and minority culture and religion were ostensibly protected. The minority areas also benefited from substantial government investment. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Yet the attention to minority rights took place within the larger framework of strong central control. Minority nationalities, many with strong historical and recent separatist or anti-Han tendencies, were given no rights of self-determination. With the special exception of Tibet in the 1950s, Beijing administered minority regions as vigorously as Han areas, and Han cadres filled the most important leadership positions. Minority nationalities were integrated into the national political and economic institutions and structures. Party statements hammered home the idea of the unity of all the nationalities and downplayed any part of minority history that identified insufficiently with China Proper. Relations with the minorities were strained because of traditional Han attitudes of cultural superiority. Central authorities criticized this "Han chauvinism" but found its influence difficult to eradicate.

“Pressure on the minority peoples to conform were stepped up in the late 1950s and subsequently during the Cultural Revolution. Ultraleftist ideology maintained that minority distinctness was an inherently reactionary barrier to socialist progress. Although in theory the commitment to minority rights remained, repressive assimilationist policies were pursued. Minority languages were looked down upon by the central authorities, and cultural and religious freedom was severely curtailed or abolished. Minority group members were forced to give up animal husbandry in order to grow crops that in some cases were unfamiliar. State subsidies were reduced, and some autonomous areas were abolished. These policies caused a great deal of resentment, resulting in a major rebellion in Tibet in 1959 and a smaller one in Xinjiang in 1962, the latter bringing about the flight of some 60,000 Kazak herders across the border to the Soviet Union. Scattered reports of violence in minority areas in the 1966-76 decade suggest that discontent was high at that time also.

“After the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1976, policies toward the ethnic minorities were moderated regarding language, religion and culture, and land-use patterns, with the admission that the assimilationist policies had caused considerable alienation. The new leadership pledged to implement a bona fide system of autonomy for the ethnic minorities and placed great emphasis on the need to recruit minority cadres.

Go West

As early as the 1950s, the government began to organize and fund migration for land reclamation, industrialization, and construction in the interior and frontier regions. Land reclamation was carried out by state farms located largely in Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region and Heilongjiang Province. Large numbers of migrants were sent to such outlying regions as Nei Monggol Autonomous Region and Qinghai Province to work in factories and mines and to Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region to develop agriculture and industry. In the late 1950s, and especially in the 1960s, during the Cultural Revolution, many city youths were sent to the frontier areas. Much of the resettled population returned home, however, because of insufficient government support, harsh climate, and a general inability to adjust to life in the outlying regions. China's regional population distribution was consequently as unbalanced in 1986 as it had been in 1953. [Source: Library of Congress]

As part of the “Go West” campaign a number of recently graduated doctors, teachers, engineers and agronomists are heading to Xinjiang, Tibet, Yunnan and other western provinces to offer their services at local clinics, schools and other facilities in remote, undeveloped areas. China has a tradition of sending people with expertise to the countryside to help and live among peasants. Each year about 10,000 Peace-Corps-like volunteers are sent by the Communist Party Youth League to underdeveloped areas. Young people are increasingly eager to take part in such endeavors even though they only receive $80 a month in living expenses and salary. In 2006 there were 60,000 applicants for the 10,000 positions. The Go West program is also involved in developing tourism (See Xinjiang).

Later History Minority Policy in China

Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese government in the mid-1980s was pursuing a liberal policy toward the national minorities. Full autonomy became a constitutional right, and policy stipulated that Han cadres working in the minority areas learn the local spoken and written languages. Significant concessions were made to Tibet, historically the most nationalistic of the minority areas. The number of Tibetan cadres as a percentage of all cadres in Tibet increased from 50 percent in 1979 to 62 percent in 1985. In Zhejiang Province the government formally decided to assign only cadres familiar with nationality policy and sympathetic to minorities to cities, prefectures, and counties with large numbers of minority people. In Xinjiang the leaders of the region's fourteen prefectural and city governments and seventy-seven of all eighty-six rural and urban leaders were of minority nationality. [Source: Library of Congress]

Dru C. Gladney wrote in the Wall Street Journal: “The country’s policy toward minorities involves official recognition, limited autonomy and unofficial efforts at control. Although totaling only 9 percent of the population, they are concentrated in resource-rich areas spanning nearly 60 percent of the country’s landmass and exceed 90 percent of the population in counties and villages along many border areas of Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia and Yunnan. Xinjiang occupies one-sixth of China’s landmass, with Tibet the second-largest province. [Source: By Dru C. Gladney, Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2009, Dru Gladney is president of the Pacific Basin Institute at Pomona College]

“Surprisingly, it has now become popular, especially in Beijing, for people to come out as Manchus or other ethnic groups. While the Han population grew 10 percent from 1982 to 1990, the minority population grew 35 percent overall — from 67 million to 91 million. The Manchus, long thought to have been assimilated into the Han majority, added three autonomous districts and increased their population by 128 percent from 4.3 million to 9.8 million. The population of the Gelao people in Guizhou shot up an incredible 714 percent in just eight years. These rates reflect more than a high birthrate; they indicate category-shifting, as people redefine their nationality from Han to minority or from one minority to another. In inter-ethnic marriages, parents can decide the nationality of their children, and the children themselves can choose their nationality at age 18.”

Yugurs — Buddhist Uyghurs

"Why is it still popular to be officially ethnic in today’s China? This is an interesting question given the riots in Xinjiang recently and in Tibet last year, not to mention the generally negative reporting in the Western press about minority discrimination in China. By the mid-1980s, it had become clear that those groups identified as official minorities were beginning to receive real benefits from the implementation of several affirmative action programs. The most significant privileges included permission to have more children (except in urban areas, minorities were generally not bound by the one-child policy), pay fewer taxes, obtain better (albeit Mandarin Chinese) education for their children, have greater access to public office, speak and learn their native languages, worship and practice their religion (often including practices such as shamanism that are still banned among the Han) and express their cultural differences through the arts and popular culture.

Xi Jinping’s Policy Towards Ethnic Minorities in China

James A. Millward wrote in the New York Times: “In its first decades, the P.R.C. tacitly acknowledged this past and proudly proclaimed its identity as a multinational state. But now, under President Xi Jinping, the C.C.P. is actively working to erase the cultural and political diversity that is the legacy of its imperial precedents. The early P.R.C., then, recognized and drew upon the Qing tradition with flexible approaches to diversity and sovereignty. But over the years, especially since Mr. Xi came to power in 2012, the C.C.P. has abandoned its relatively tolerant tradition while intensifying ethnic assimilationism and political rigidity. Today, rather than celebrating the uniqueness of individual cultures, the C.C.P. increasingly promotes a unitary category called “zhonghua,” a kind of pan-Chinese identity. Though supposedly all-inclusive, the customs and characteristics of “zhonghua” are practically identical to those of the Han. [Source: James A. Millward, New York Times, Mr. Millward is a China scholar and historian., October 1, 2019. Millward, a professor of history at Georgetown University, is the author of “Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang” and “The Silk Road: A Very Short Introduction”]

“The government now calls Mandarin, previously known as the “Han-language” (“hanyu”), the “national language” (“guoyu”) and more forcefully pushes its use in schools and public settings, even though linguistic freedom and the official use of local languages are guaranteed by the Constitution. The P.R.C. once actively supported publishing and bilingual education in non-Han languages. Now, Uyghur bookstores in Xinjiang are empty and shuttered. In both Xinjiang and Tibet, bilingual education has been replaced by Mandarin schools, and proponents of Uyghur and Tibetan language-learning have been persecuted. Authorities have scrubbed Arabic script from public places across China — including the word “halal” on the front of stores and restaurants. TV shows in non-Mandarin Chinese languages are disappearing from P.R.C. broadcasts. Cantonese is under pressure, in Hong Kong and neighboring Guangzhou province.

“Similarly, in the name of Sinicizing religion, Mr. Xi’s party-state is razing mosques and churches and has demolished huge swaths of the Tibetan Buddhist monastic centers of Larung Gar and Yachen Gar, expelling monks and nuns and interning some of them in so-called re-education camps like those in which it now holds some one million Uyghurs. The C.C.P. has tried to impose “patriotic education” in Hong Kong schools to enforce the teaching of the party’s version of history. When Taiwanese voters elected a leader Beijing didn’t like in 2016, Mr. Xi threatened military force and prevented mainland tourists from visiting the island.

Hani Village

“Such policies undercut the P.R.C.’s legacy of administrative flexibility and relative ethnic tolerance, as well as expose it to international criticism, exacerbating tensions while undermining the party’s legitimacy. What’s more, concentration camps will not turn Uyghurs and Kazakhs into faithful “zhonghua” Chinese who eat pork and disregard Ramadan. Violent policing will not make Hong Kongers abandon calls for the autonomy promised in the territory’s mini-Constitution. Religious repression and demonizing the Dalai Lama will not endear Tibetans to the party. Military threats will not make Taiwanese feel closer to the mainland.

“Mr. Xi’s vain dream of political and cultural homogeneity not only runs counter to Chinese traditional approaches to diversity. His assimilationism also incites the very instability the C.C.P. has long hoped to avoid. For the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in July 2021 ethnic minorities including Uyghurs were forced to leave Beijing. Around major political events, China spares no expense in ‘stability maintenance’ in order to ensure everything goes off without a hitch.

Efforts to Help Minorities in China

The government — on paper anyway — protects the customs of minorities by law, and encourages them to participate in the government and has set up special development programs to help them. During televised coverage of Communist party meetings, cameras often pan across all the minorities dressed in their traditional costumes in the People's Hall. For minorities there are five autonomous regions, 30 autonomous prefectures, 124 autonomous counties.

Because minorities in China are exempt from some of China's birth control restrictions their growth rates are as much as triple that of the Han Chinese majority. The Chinese government allows this at least partly to assuage worries by the minorities about being outnumbered in their homelands by migrating Han Chinese.

Minorities have been beneficiaries of some affirmative action policies: they have sometimes been given preferences for university admission and government promotions. The aim of these policies however. it often seems, is to recruit the best and brightest minority group members to join the Communist Party. To recruit loyal party members from China's non-Han ethnic groups the Chinese government set up the National Minorities Institute in Beijing.

Partly due to the fact that he had served as Tibet party secretary from 1988 to 1992, Former President Hu Jintao was personally involved with Beijing’s policy toward ethnic minorities. And the majority of senior cadres in both Tibet and Xinjiang, including their party bosses — Zhang Qingli and Wang Lequan, respectively — -are senior members of the president’s so-called Communist Youth League (CYL) Faction. These Hu protégés, however, are also hardliners known to have neither sympathy for local culture nor sensitivity toward their charges’ sentiments. Zhang, for example, publicly labeled the Dalai Lama — -the revered leader of the exiled Tibetan movement — -a wolf in sheep’s clothing. [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, July 23 2009]

Minorities Moved from Their Villages in China Anti-Poverty Campaign

Reporting from Chengbei Gan’en in Sichuan province's Liangshan prefecture,Sam McNeil of Associated Press wrote: Under a portrait of President Xi Jinping, Ashibusha sits in her freshly painted living room cradling her infant daughter beside a chair labeled a “gift from the government.” The mother of three is among 6,600 members of the Yi ethnic minority who were moved out of 38 mountain villages in China’s southwest and into a newly built town in an anti-poverty initiative. Farmers who tended mountainside plots were assigned jobs at an apple plantation. Children who until then spoke only their own tongue, Nuosu, attend kindergarten in Mandarin, China’s official language. “Everyone is together,” said Ashibusha, 26. [Source: Sam McNeil, Associated Press, September 22, 2020]

“While other nations invest in developing poor areas, Beijing doesn’t hesitate to operate on a more ambitious scale by moving communities wholesale and building new towns in its effort to modernize China. The ruling Communist Party has announced an official target of ending extreme poverty by the end of the year, ahead of the 100th anniversary of its founding in 2021. The party says such initiatives have helped to lift millions of people out of poverty. But they can require drastic changes, sometimes uprooting whole communities. They fuel complaints the party is trying to erase cultures as it prods minorities to embrace the language and lifestyle of the Han, who make up more than 90 percent of China's population.

Chinese authorities invited reporters to visit Chengbei Gan’en and four other villages — Xujiashan, Qingshui, Daganyi and Xiaoshan — that are part of what authorities see as a successful development project for the Yi in Sichuan province's Liangshan prefecture. The initiative is one of hundreds launched over the past four decades to spread prosperity from China’s thriving east to the countryside and west. “Mass relocations still are carried out because some mountainous and other areas are too isolated, said Wang Sangui, president of the China Poverty Alleviation Research Institute of Renmin University in Beijing. “It is impossible to solve the problem of absolute poverty without relocation," he said.

“In Sichuan, which includes some of China’s poorest areas, 80 billion yuan ($12 billion) has been spent to date to relocate 1.4 million people, according to Peng Qinghua, the provincial party secretary. He said that included building 370,000 new homes and over 110,000 kilometers (68,000 miles) of rural roads. Older villagers welcome the jump in living standards. “You can eat whatever you like now,” said Wang Deying, an 83-year-old grandmother of five. “Now even the pigs eat rice.”

In Chengbei Gan’en, 420 million yuan ($60 million) was spent to build 1,440 apartments in 25 identical white buildings, a clinic, a kindergarten and a center for the elderly. Craftspeople sell silver jewelry, painted cow skulls and traditional clothing that are popular with Han tourists. Yi women can study to become nannies, a profession in demand in urban China, in classes taught with pink plastic dolls. Roadside signs call on people to speak the official language. “Mandarin, please, after you enter kindergarten.” “Speak Mandarin well, it’s convenient for everyone.” “Everyone speaks Mandarin, flower of civilization blooms everywhere.” Murals on buildings depict the Yi with members of the Han majority in amicable scenes. One shows a baby holding a heart emblazoned with the ruling party’s hammer-and-sickle symbol. In one village, Xujiashan, annual household income has risen from 1,750 yuan ($260) in 2014 to 11,000 yuan ($1,600), according to its deputy secretary, Zhang Lixin.

Ulterior Motive for Uprooting Chinese Minorities

Sam McNeil of Associated Press wrote:“Development initiatives can lead to political tension because many have strategic goals such as strengthening control over minority areas by encouraging nomads to settle or diluting the local populace with outsiders. The party faces similar complaints that it is suppressing local languages in Tibet and the Muslim region of Xinjiang in the northwest. [Source: Sam McNeil, Associated Press, September 22, 2020]

“The party boss for Liangshan prefecture acknowledged its initiative isn’t purely economic. Authorities want to eliminate “outdated habits,” said the official, Lin Shucheng. He listed complaints about extravagant dowries, too many animals butchered for funerals and poor hygiene. “We are fighting against traditional forces of habit,” he said. At the same time, ruling party officials say they are preserving Nuosu, a Yi language, through bilingual education in schools and government support for a Nuosu newspaper and TV show. “We protect and promote the learning, use and development of the Yi language,” the provincial party secretary, Peng, told reporters.

“The party might be willing to promote Nuosu because, unlike in Tibet or Xinjiang, the Yi demand no political change, said Stevan Harrell, a University of Washington anthropologist who has spent more than three decades visiting and studying the region. “There is no ‘splittism’ in Liangshan,” Harrell said, using the party’s term for activists who want more autonomy for Tibet and Xinjiang. “So it is kind of safe to have the Yi language as a medium of education,” said Harrell. “And it scores points for the government against those people who rightly point out that Uyghur and Tibetan languages are being severely suppressed.”

Education of Minorities in China

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “ Because the Communist Party wanted to promote a unified country, it maintained that non-Han populations had the right to preserve their own languages, customs, and religions over a long period of time until all minorities would ultimately "melt together." In the meantime, the government also insisted that minorities were backward in their customs, economy, and political consciousness. Therefore, they needed assistance from the Han people to achieve a developed socialist country. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“As a result of these contradictory policies, China has developed one of the oldest and largest programs of state-sponsored affirmative action for ethnic minorities. By 1950 the government had established 45 special minority primary schools and 8 provincial minority secondary schools. The minority students in these schools were provided free education, books, and school supplies and were subsidized for food and housing (Hansen 1990). For the long-term political goal, the government also focused on the education of minority cadres. An important institution to accomplish this goal is minzu xueyuan (special minority institutes), which trained minority cadres to work in minority regions as representatives of the Communist party and government. In college entrance examinations, minorities are given additional points to give them greater access to higher education—20 points are automatically added to their scores if they apply to minority institutes, or 5 points are added if they apply to other schools. Also, in many cases, minority students are allowed to take the examinations in their indigenous languages and later enroll in classes taught in Mandarin.

Many prominent universities now have minzu ban (ethnic classes or cohorts). Since the early 1980s, there have also been one-year yuke ban (preparatory courses) for minorities at key universities and minority institutes. These classes, which may be arranged by agreement between minority areas and universities, can serve students who failed to enter a university through the national enrollment system. Minority students also benefit from quotas that set aside a certain percentage of the spaces in classes for them. Furthermore, governments at different levels tried to strengthen the training of local teachers and re-establish bilingual education, particularly among Tibetans, Mongols, and Uygurs. The autonomous governments of minorities are allowed to decide which kinds of schools to establish, the length of schooling, whether a special curriculum is needed, which languages to teach in addition to Chinese, and how to recruit students. The central government also decided that minority students studying in cities should be allocated jobs in their home-counties after graduation in order to ensure that poor and underdeveloped rural minority areas would benefit from minority higher education. In exchange for the preferential policies, minorities are expected to support China's construction by providing more natural resources.

“In spite of governmental preferential policies, many minority areas are still characterized by low levels of school enrollment and educational attainment. In 1990, the level of illiteracy of the national minorities as a whole (30.8 percent) is markedly higher than that of all Han combined at 21.5 percent. While minority students continue to do relatively well in terms of opportunities to enter higher education, they are increasingly disadvantaged in their access to the job market upon graduation. Furthermore, both minority men and women are highly disadvantaged in applying to enter graduate school, due to the foreign language requirement. It is not easy for them to reach an adequate level in a foreign language when they must master Chinese in addition to their own language and then learn the foreign language through the medium of Chinese. Nor is there much evidence of affirmative action for minority students at the graduate level. Also, the fact that many minority undergraduates intend to become cadres, rather than academics, contributes to the scarcity of minority graduate students. In 1993, only 3 percent of graduate students were minorities.

In December 2008, the government announced that beginning in primary school students would study “ethnic unity.” The move was widely seen as a response to unrest in Tibet and Xinjiang.

See PUSHING MANDARIN AND TRYING TO PRESERVE OTHER CHINESE DIALECTS AND LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com Chinese Replacing the Mongolian Language in Inner Mongolia Schools and Protests Under MONGOL ISSUES, ANGER, ACTIVISM AND PROTESTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN LANGUAGE: GRAMMAR, DIALECTS, THREATS AND NAMES factsanddetails.com ; EDUCATION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

Education of Minorities in China: Naomi Furnish Yamada's PhD dissertation is on contemporary minority education. : Gerard Postiglione from Univ of Hong Kong has written extensively on minority education and language policy issues. His works include as "China's National Minorities and Education Changes" Journal of Contemporary Asia vol. 22, no. 1 (1992); "China's National Minority Education: Culture, Schooling, and Development" by Gerard A. Postiglione, ed. (New York: Falmer, 1999); "Minority Movement and Education" by Wang, S; "In China's Minorities on The Move: Selected Case Studies", edited by R. R. Iredale, N. Bilik, and Fei Guo,32-50. Armonk, N. Y.: Sharpe, 2003.

Communist-Party-Supported Minority Language Databases

Bruce Hume wrote on Ethnic China Lit: According to China’s Ministry of Education , several minority language projects underway during the current 12th Five-year Plan (2011-15) have been appraised and approved by experts. They are: 1) Database of Modern Tibetan Grammar Research; and 2) Database of Daur, Evenki and Oroqen Voice Acoustic Parameters. Undertaken by the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences , applications for these databases include promotion of minority language education, language engineering research, and in the case of the Tibetan database, text annotation and machine translation. [Source: Bruce Hume Ethnic China Lit:]

“It will be interesting to see where all this hard work leads. Many minority languages in China still have no written form and research into them is often restricted to territory and peoples within the PRC, even when speakers of the language straddle international borders. The Evenki language, spoken by several tens of thousands of Evenki in China, Russia and Mongolia, is a case in point. According to an expert cited in Wikipedia (Evenki Language), in Russia, ‘since the 1930s “folklore, novels, poetry, numerous translations from Russian and other languages, textbooks, and dictionaries have all been written in Evenki.” Evenki elementary and middle school textbooks have also been published. As I understand it, however, nothing similar has taken place on the Chinese side of the border.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022