MINORITIES IN CHINA

The Chinese government counts 55 minorities and 56 ethnic groups, including the majority Han Chinese. The population of ethnic minorities was 125.5 million, or 8.89 percent according to the 2020 Chinese census. Compared with the 2010 census, the ethnic minorities population increased by 10.26 percent compared 4.93 percent for Han Chinese population, who numbered about 1.29 billion in 2020. China’s ethnic minorities account for a population that is larger that the populations of all but 11 countries in the world. There are almost as many members of ethnic minorities in China as there are people in Mexico.

Many minorities live in compact communities at the upper reaches of large rivers and in border regions. Centuries of isolation and autonomy have made many of them linguistically and culturally distinct from the majority Han. Most of these minorities live in southern China, Tibet or the western Province of Xinjiang or near the borders of Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, India, Russia, Mongolia, North Korea and the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

With the exception of the Hui and She ethnic groups, the first languages of the minority peoples in China belong to language families other than Chinese. Many minority members speak their own language at home and may also speak the Chinese dialect of their region and have some familiarity with the language of neighboring minorities. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 ]

Minorities make up the bulk of the population in 60 percent of China's territory, namely in Tibet and Xinjiang. These areas contain important natural resources such as minerals, timber, water and petroleum. There are 19 ethnic groups with over a million people. They include Tibetans, Mongolians, Uyghurs, Zhuang, Manchus and Koreans. The smallest ethnic, the Lhoba, has only about 2,300 members. Many of the ethnic groups still dress in traditional clothes though more are probably assimilated and don’t look so different from Han Chinese. Some of them have very distinct customs. The largest of the 55 recognized minorities in China is the Zhuang, over 20 million people. They are concentrated mainly in Guangxi province in southern China. The smallest minority is the Lhoba in Tibet with only 3,680 people.

Ethnicity has been incorporated into views about Chinese nationalism. Pioneering, early 20th century, Chinese leader Sun Yat-sen described China’s main ethnic groups — the Han, Manchu, Hui, Mongolian and Tibetans — as the “five fingers” of China. With one of these five fingers missing the Chinese feel their nation is not whole — a view aggressively promoted today by the Communist Party. According to the 2010 census, about 4 percent of Beijing's population, or 800,000 people, belonged to ethnic minorities, most of whom were Mongolian or Manchurian. Ethnic tensions are rarely reported in the capital. [Source: Patrick Boehler, South China Morning Post, May 13, 2013]

See Separate Articles: DIVERSITY, ASSIMILATION AND ETHNIC RELATIONS AND TENSIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PROBLEMS FACED BY MINORITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; MINORITIES AND THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE DIALECTS AND LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com; PUSHING MANDARIN AND TRYING TO PRESERVE OTHER CHINESE DIALECTS AND LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com; PEOPLE OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; HAN CHINESE factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Sources: Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; Paul Noll site: paulnoll.com ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ethnic Minorities of China” by Xu Ying & Wang Baoqin Amazon.com; “Handbook on Ethnic Minorities in China” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “Minority Peoples of China” by OMF International Amazon.com; “China's Minority Nationalities” (1984) Amazon.com; “China's Minority Nationalities” by Ma Yin (1989) Amazon.com; China's Minority Nationalities” by Red Sun Publishers (1977) Amazon.com; “China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xiao Xiaoming Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Vol. 6, Russia and Eurasia/China” (1994) by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond Amazon.com; “Ethnic Groups in China” by Wang Can Amazon.com; Identity and Ethnicity: “Ethnicity in China: A Critical Introduction” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “Lesser Dragons: Minority Peoples of China” by Michael Dillon Amazon.com; “The Classification of Ethnic Groups in Ancient China” by Wang Wenguang and Duan Hongyun Amazon.com; “Ethnic Minorities in Socialist China: Development, Migration, Culture, and Identity” by Han Xiaorong and The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Amazon.com; “Invisible China: A Journey Through Ethnic Borderlands” by Colin Legerton and Jacob Rawson Amazon.com; “Ethnic Minorities of China” by Ying Xu and Baoqin Wang Amazon.com; “Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers” by Stevan Harrell Amazon.com;

What Constitutes an Ethnic Minority in China

Wa (Va) Villagers

The Chinese define a nationality as a group of people of common origin living in a common area, using a common language, and having a sense of group identity in economic and social organization and behavior. Classifications are often based on self-identification, and it is sometimes and in some locations advantageous for political or economic reasons to identify with one group over another. Most minorities have their own language. Some have their own script, although some of these have fallen into disuse under Communist rule. Most minorities live in a specific area of China.

Among scholars there is some debate over how the groups were defined and who belongs in which group. There are many examples of small groups being lumped together with larger groups which they have little in common with linguistically and culturally. Some officially-designated groups — such as the Nu — seem be comprised of groups that are different enough they should be regarded as distinct ethnic groups but are conveniently grouped together based on geography. [Source: Library of Congress]

Ethnic distinctions are largely linguistic and religious rather than racial. Although non-Han peoples are relatively few in number, they are politically significant because they occupy about two-thirds of China's land area. Most live in strategic frontier territories in the southwest, Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia and have religious or ethnic ties with groups in adjoining nations. Since the take over of China, by the Communists in 1949, the dominance of non-Han groups in their traditional homelands — such as Tibet, Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia — has been weakned as Han Chinese have entered these regions in increasing numbers since 1950.[Source: U.S. State Department report, December 1996]

Haoming Gong and Xin Yang wrote in “Reconfiguring Class, Gender, Ethnicity and Ethics in Chinese Internet Culture”: The Chinese term minzu (ethnicity) “incorporates and intermingles different levels of race, nationality, and ethnicity in different social, historical, and political contexts” and thus “does not have an exact equivalent in English”. The Chinese minzu is a highly “definitive and performative” imagined identity closely linked to Chinese nationalism and other ideological projects. At the same time, minzu is a volatile, contingent concept that is caught up in contestations between different sociocultural actors and forces. The performative nature of Chinese minzu identity, together with its entanglement in political and legal discourses both enables and constrains non-Han Chinese citizens. [Source:“Reconfiguring Class, Gender, Ethnicity and Ethics in Chinese Internet Culture” by Haoming Gong and Xin Yang (Routledge, 2017) Reviewed by Jamie J. Zhao, MCLC Resource Center Publication, September, 2017]

How China’s Minorities Were Determined

Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”:“The present listing of the various nationalities follows an intensive period of survey research by ethnologists, historians, linguists, folklorists, and government cadres during the 1950s. There are recognized problems with the categories that emerged. Initially, only 11 nationalities received official recognition, although over 400 separate groups had applied. According to Tom Mullaney’s "Coming to Terms with the Nation: Ethnic Classification in Modern China", in the first census of the PRC conducted in 1953-4, over four hundred minzu were recorded, more than half by Yunnan Province alone. Over time, additional groups were added to the list and some populations reclassified. Jino, for example, were originally classified as Dai, and Daur were identified as Mongols. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Some requests for recognition were unsuccessful. For instance, in Guizhou some 200,000 people referred to as the Chuanqing were denied minority status and classified as Han. The basis for the decision is that their genealogies trace back to Ming occupation troops and conscripted laborers left behind to cultivate the land and open the frontier in the twelfth century. The men married women from neighboring ethnic groups, and their communities developed a distinct local culture over eight centuries. Even so, the evidence of forefathers of Han ancestry negates their claims to a separate ethnicity.

Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, there has been a new wave of applications for recognition. In Guizhou alone, some eighty groups (close to one million people) petitioned for recognition or reclassification. Most of the remaining contested groups are small (20,000 or less) and, given the difficulty of finding information on them outside of neibu documents (government classified materials), they will not be discussed in this volume.

Largest Ethnic Groups in China

Tibetan girl

The largest ethnic group in China is the Han Chinese. Based on the 2020 census, about 91 percent of the population of China is classified as Han Chinese. This amounts to about 1.3 billion people. Among the main non-Chinese minorities are 1) the Zhuang, a Thai-speaking group, found principally in Guangxi; 2) the Uyghurs, a Turkic Muslim people who live mainly in Xinjiang; 3) the Hui (Chinese Muslims), found chiefly in Ningxia, Gansu, Henan, and Hebei; 4) the Miao, widely distributed throughout the mountainous areas of southern China; 5) Manchu, concentrated in Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning; 6) Yi, formerly called Lolo, who live on the borders of Sichuan and Yunnan; 7) the Tibetans, concentrated in Tibet, western Sichuan and Qinghai; and 8) the Mongols, found chiefly in the Mongolian steppes; and 9) the Koreans, who are concentrated in Jilin Province. Other minority nationalities, with estimated populations of more than one million, included the Tujia, Bouyei, Dong, Yao, Ba, Hani, Li and the Kazakhs. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Largest Ethnic Groups in 2010: 1) Han: 1,220,844,520 (91.6474 percent); 2) Zhuang: 16,926,381 ( 1.2700 percent); 3) Hui: 10,586,087 (0.7943 percent); 4) Manchu: 10,387,958 (0.7794 percent); 5) Uyghurs: 10,069,346 (0.7555 percent); 6) Miao: 9,426,007 (0.7072 percent); 7) Yi: 8,714,393 ( 0.6538 percent); 8) Tujia: 8,353,912 ( 0.6268 percent); 9) Tibetan: 6,282,187 (0.4713 percent); 10) Mongol: 5,981,840 ( 0.4488 percent); 11) Dong 2,879,974 (0.2161 percent); 12) Bouyei: 2,870,034 (0.2153 percent); 13) Yao: 2,796,003 (0.2098 percent); 14) Bai: 1,933,510 ( 0.1451 percent);15) Korean: 1,830,929 (0.1374 percent); 16) Hani: 1,660,932 ( 0.1246 percent); 17) Li: 1,463,064 ( 0.1098 percent); 18) Kazakh: 1,462,588 ( 0.1097 percent); 19) Dai: 1,261,311 (0.0946 percent); 20) She: 708,651 (0.0532 percent). [Source: People’s Republic of China censuses]

The largest minorities in China in 2000 (according to the 2000 census) were: 1) Zhuang (16.1 million), 2) Manchu (10.6 million), 3) Hui (9.8 million), 4) Miao (8.9 million), 5) Uyghur (8.3 million), 6) Tujia (8 million), 7) Yi (7.7 million), 8) Mongol (5.8 million), 9) Tibetan (5.4 million), 10) Bouyei (2.9 million), 11) Dong (2.9 million), 12) Yao (2.6 million), 13) Korean (1.9 million), 14) Bai (1.8 million), 15) Hani (1.4 million), 16) Kazakh (1.2 million), 17) Li (1.2 million), and 18) Dai (1.1 million).

Chinese Ethnic Group Numbers

Officially Recognized Ethnic Groups in Mainland China (rank, ethnic group: population in 2020, 2010, 2000 and 1990):

1) Han: 1,286,310,000 (91.11 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 1,220,844,520 (91.6474 percent) in 2010; 1,139,773,008 in 2000; 1,042,482,187 in 1990.

Minority groups: 25,470,000 (8.89 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census.

2) Zhuang: 19,568,546 (1.39 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 16,926,381 ( 1.2700 percent) in 2010; 16,187,163 in 2000; 15,489,630 in 1990.

3) Uyghurs: 11,774,538 (0.84 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 10,069,346 (0.7555 percent) in 2010; 8,405,416 in 2000; 7,214,431 in 1990.

4) Hui: 11,377,914 (0.81 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 10,586,087 (0.7943 percent) in 2010; 9,828,126 in 2000; 8,602,978 in 1990.

5) Miao: 11,067,929 (0.79 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 9,426,007 (0.7072 percent) in 2010; 8,945,538 in 2000; 7,398,035 in 1990.

6) Manchu: 10,423,303 (0.74 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 10,387,958 (0.7794 percent) in 2010; 10,708,464 in 2000; 9,821,180 in 1990.

7) Yi: 9,830,327 (0.70 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 8,714,393 ( 0.6538 percent) in 2010; 7,765,858 in 2000; 6,572,173 in 1990.

8) Tujia: 9,587,732 (0.68 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 8,353,912 ( 0.6268 percent) in 2010; 8,037,014 in 2000; 5,704,223 in 1990.

9) Tibetan: 7,060,731 (0.50 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census. 6,282,187 (0.4713 percent) in 2010; 5,422,954 in 2000; 4,593,330 in 1990.

10) Mongol: 6,290,204 (0.45 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 5,981,840 ( 0.4488 percent) in 2010; 5,827,808 in 2000; 4,806,849 in 1990.

[Source: People’s Republic of China censuses]

11) Bouyei: 3,576,752 (0.25 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 2,870,034 (0.2153 percent) in 2010; 2,973,217 in 2000; 2,545,059 in 1990.

12) Dong 3,495,993 (0.25 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 2,879,974 (0.2161 percent) in 2010; 2,962,911 in 2000; 2,514,014 in 1990.

13) Yao: 3,309,341 (0.23 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 2,796,003 (0.2098 percent) in 2010; 2,638,878 in 2000; 2,134,013 in 1990.

14) Bai: 2,091,543 (0.15 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 1,933,510 ( 0.1451 percent) in 2010; 1,861,895 in 2000; 1,594,827 in 1990.

15) Hani: 1,733,166 (0.12 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 1,660,932 ( 0.1246 percent) in 2010; 1,440,029 in 2000; 1,253,952 in 1990.

16) Korean: 1,702,479 (0.12 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 1,830,929 (0.1374 percent) in 2010; 1,929,696 in 2000; 1,920,597 in 1990.

17) Li: 1,602,104 (0.11 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 1,463,064 ( 0.1098 percent) in 2010; 1,248,022 in 2000; 1,110,900 in 1990.

18) Kazakh: 1,562,518 (0.11 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 1,462,588 ( 0.1097 percent) in 2010; 1,251,023 in 2000; 1,111,718 in 1990.

19) Dai: 1,329,985 (0.09 percent of the population of China) in 2020 according to the 2020 census; 1,261,311 (0.0946 percent) in 2010; 1,159,231 in 2000; 1,025,128 in 1990.

20) She: 708,651 (0.0532 percent) in 2010; 710,039 in 2000; 630,378 in 1990.

map from 1983

Rank, Ethnic group: population in 2010, 2000 and 1990:

21) Lisu: 702,839 (0.0527 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 635,101 in 2000; 574,856 in 1990.

22) Dongxiang: 621,500 (0.0466 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 513,826 in 2000; 373,872 in 1990.

23) Gelao: 550,746 in (0.0413 percent) 2010; 579,744 in 2000; 437,997 in 1990.

24) Lahu: 485,966 (0.0365 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 453,765 in 2000; 411,476 in 1990.

25) Wa (Va): 429,709 (0.0322 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 396,709 in 2000; 351,974 in 1990.

26) Sui: 411,847 (0.0309 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 407,000 in 2000; 345,993 in 1990.

27) Nakhi: 326,295 (0.0245 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 309,477 in 2000; 278,009 in 1990.

28) Qiang: 309,576 (0.0232 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 306,476 in 2000; 198,252 in 1990.

29) Tu: 289,565 (0.0217 percent) in 2010; 241,593 in 2000; 191,624 in 1990.

30) Mulao: 216,257 (0.0162 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 207,464 in 2000; 159,328 in 1990.

31) Xibe: 190,481 (0.0143 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 189,357 in 2000; 172,847 in 1990.

32) Kyrgyz: 186,708 (0.0140 percent) in 2010; 160,875 in 2000; 141,549 in 1990.

33) Jingpo: 147,828 (0.0111 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 132,158 in 2000; 119,209 in 1990.

34) Daur: 131,992 (0.0099 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 132,747 in 2000; 121,357 in 1990.

35) Salar: 130,607 (0.0098 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 104,521 in 2000; 87,697 in 1990.

36) Blang: 119,639 (0.0090 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 91,891 in 2000; 82,280 in 1990.

37) Maonan: 101,192 (0.0076 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 107,184 in 2000; 71,968 in 1990.

38) Tajik: 51,069 (0.0038 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 41,056 in 2000; 33,538 in 1990.

39) Pumi: 42,861 (0.0032 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 33,628 in 2000; 29,657 in 1990.

40) Achang: 39,555 (0.0030 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 33,954 in 2000; 27,708 in 1990.

41) Nu: 37,523 ((0.0028 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 28,770 in 2000; 27,123 in 1990.

42) Ewenki: 30,875 (0.0023 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 30,545 in 2000; 26,315 in 1990.

43) Jin (Gin): 28,199 (0.0021 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 22,584 in 2000; 18,915 in 1990.

44) Jino: 23,143 (0.0017 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 20,899 in 2000; 18,021 in 1990.

45) De'ang: 20,556 (0.0015 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 17,935 in 2000; 15,462 in 1990.

46) Baoan: 20,074 (0.0015 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 16,505 in 2000; 12,212 in 1990.

47) Russian: 15,393 (0.0012 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 15,631 in 2000; 13,504 in 1990.

48) Yugur: 14,378 (0.0011 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 13,747 in 2000; 12,297 in 1990.

49) Uzbek: 10,569 ((0.0008 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 12,423 in 2000; 14,502 in 1990.

50) Monba: 10,561 ((0.0008 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,928 in 2000; 7,475 in 1990.

51) Oroqen: 8,659 (0.0006 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,216 in 2000; 6,965 in 1990.

52) Derung: 6,930 (0.0005 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 7,431 in 2000; 5,816 in 1990.

53) Hezhen: 5,354 (0.0004 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 4,664 in 2000; 4,245 in 1990.

54) Gaoshan: 4,009 (0.0003 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 4,488 in 2000; 2,909 in 1990.

55) Lhoba: 3,682 (0.0003 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 2,970 in 2000; 2,312 in 1990.

56) Tatars: 3,556 (0.0003 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 4,895 in 2000; 4,873 in 1990.

Undistinguished: 640,101 (0.0480 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 734,438 in 2000; 749 341 in 1990.

Naturalized Citizen: 1,448 (0.0001 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 941 in 2000; 3,421 in 1990.

Provinces and Province-Like Units of China

Chinese Minority by Region

Northern China (size ranking of China's 55 minorities, ethnic group: population in 2010, 2000 and 1990)

3) Hui: 10,586,087 (0.7943 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 9,828,126 in 2000; 8,602,978 in 1990.

4) Manchu: 10,387,958 (0.7794 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 10,708,464 in 2000; 9,821,180 in 1990.

10) Mongol: 5,981,840 (0.4488 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 5,827,808 in 2000; 4,806,849 in 1990.

15) Korean: 1,830,929 (0.1374 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 1,929,696 in 2000; 1,920,597 in 1990.

34) Daur: 131,992 (0.0099 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 132,747 in 2000; 121,357 in 1990.

42) Ewenki: 30,875 (0.0023 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 30,545 in 2000; 26,315 in 1990.

51) Oroqen: 8,659 (0.0006 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,216 in 2000; 6,965 in 1990.

53) Hezhen: 5,354 (0.0004 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 4,664 in 2000; 4,245 in 1990.

See Separate Article Minorities in Northern China factsanddetails.com

Northwest China (mostly Xinjiang and Gansu Province)

3) Hui: 10,586,087 (0.7943 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 9,828,126 in 2000; 8,602,978 in 1990.

5) Uyghur: 10,069,346 (0.7555 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,405,416 in 2000; 7,214,431 in 1990.

18) Kazakh: 1,462,588 (0.1097 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 1,251,023 in 2000; 1,111,718 in 1990.

22) Dongxiang: 621,500 (0.0466 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 513,826 in 2000; 373,872 in 1990.

29) Tu: 289,565 (0.0217 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 241,593 in 2000; 191,624 in 1990.

31) Xibe: 190,481 (0.0143 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 189,357 in 2000; 172,847 in 1990.

32) Kyrgyz: 186,708 (0.0140 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 160,875 in 2000; 141,549 in 1990.

35) Salar: 130,607 (0.0098 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 104,521 in 2000; 87,697 in 1990.

38) Tajik: 51,069 (0.0038 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 41,056 in 2000; 33,538 in 1990.

46) Baoan: 20,074 (0.0015 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 16,505 in 2000; 12,212 in 1990.

47) Russian: 15,393 (0.0012 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 15,631 in 2000; 13,504 in 1990.

48) Yugur: 14,378 (0.0011 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 13,747 in 2000; 12,297 in 1990.

49) Uzbek: 10,569 (0.0008 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 12,423 in 2000; 14,502 in 1990.

56) Tatars: 3,556 (0.0003 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 4,895 in 2000; 4,873 in 1990.

See Separate Articles Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com ; Small Minorities in Xinjiang and Western China factsanddetails.com

Southern China (mostly Guizhou and Guangxi):

2) Zhuang: 16,926,381 (1.27 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 16,187,163 in 2000; 15,489,630 in 1990.

6) Miao: 9,426,007 (0.7072 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,945,538 in 2000; 7,398,035 in 1990.

11) Dong: 2,879,974 (0.2161 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 2,962,911 in 2000; 2,514,014 in 1990.

13) Yao: 2,796,003 (0.2098 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 2,638,878 in 2000; 2,134,013 in 1990.

17) Li: 1,463,064 (0.1098 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 1,248,022 in 2000; 1,110,900 in 1990.

20) She: 708,651 (0.0532 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 710,039 in 2000; 630,378 in 1990.

23) Gelao: 550,746 (0.0413 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 579,744 in 2000; 437,997 in 1990.

26) Sui: 411,847 (0.0309 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 407,000 in 2000; 345,993 in 1990.

30) Mulao: 216,257 (0.0162 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 207,464 in 2000; 159,328 in 1990.

37) Maonan: 101,192 (0.0076 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 107,184 in 2000; 71,968 in 1990.

43) Gin: 28,199 (0.0021 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 22,584 in 2000; 18,915 in 1990.

54) Gaoshan (Taiwan): 4,009 (0.0003 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 4,488 in 2000; 2,909 in 1990.

See Separate Article Minorities in Guangxi, Guizhou and Southern China factsanddetails.com

Southwest China (mostly western Yunnan):

12) Bouyei: 2,870,034 (0.2153 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 2,973,217 in 2000; 2,545,059 in 1990.

16) Hani: 1,660,932 (0.1246 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 1,440,029 in 2000; 1,253,952 in 1990.

19) Dai: 1,261,311 (0.0946 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 1,159,231 in 2000; 1,025,128 in 1990.

21) Lisu: 702,839 (0.0527 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 635,101 in 2000; 574,856 in 1990.

24) Lahu: 485,966 (0.0365 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 453,765 in 2000; 411,476 in 1990.

25) Wa (Va): 429,709 (0.0322 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 396,709 in 2000; 351,974 in 1990.

33) Jingpo:147,828 (0.0111 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 132,158 in 2000; 119,209 in 1990.

36) Blang: 119,639 (0.0090 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 91,891 in 2000; 82,280 in 1990.

39) Pumi: 42,861 (0.0032 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 33,628 in 2000; 29,657 in 1990.

40) Achang: 39,555 (0.0030 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 33,954 in 2000; 27,708 in 1990.

44) Jino: 23,143 (0.0017 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 20,899 in 2000; 18,021 in 1990.

45) De'ang: 20,556 (0.0015 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 17,935 in 2000; 15,462 in 1990.

See Separate Article Minorities in Western Yunnan factsanddetails.com

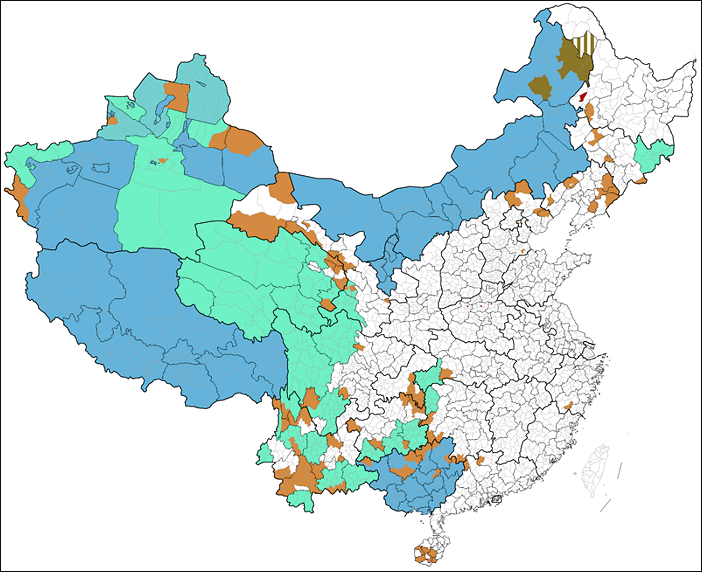

Minority Regions under Autonomous Rule Designated by the Chinese Government

Autonomous Region — blue

Autonomous Prefecture — aquamarine blue

Autonomous County — brown

Autonomous Banner — greyish brown

Ethnic district — red

Central, Southern, Western China (mostly northern Yunnan and Sichuan)

7) Yi: 8,714,393 (0.6538 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 7,765,858 in 2000; 6,572,173 in 1990.

8) Tujia: 8,353,912 (0.6268 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,037,014 in 2000; 5,704,223 in 1990.

14) Bai: 1,933,510 (0.1451 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 1,861,895 in 2000; 1,594,827 in 1990.

27) Naxi: 326,295 (0.0245 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 309,477 in 2000; 278,009 in 1990.

28) Qiang: 309,576 (0.0232 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 306,476 in 2000; 198,252 in 1990.

41) Nu: 37,523 (0.0028 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 28,770 in 2000; 27,123 in 1990.

52) Derung (Dulong): 6,930 (0.0005 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 7,431 in 2000; 5,816 in 1990.

See Separate Article Minorities in Northern Yunnan, Tibet and Central China factsanddetails.com

Tibet:

9) Tibetan: 6,282,187 (0.4713 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 5,422,954 in 2000; 4,593,330 in 1990.

50) Monba: 10,561 (0.0008 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,928 in 2000; 7,475 in 1990.

55) Lhoba: 3,682 (0.0003 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 2,970 in 2000; 2,312 in 1990.

Chinese Minority History

“At the end of the Han dynasty in the A.D. 3rd century China split into three independent kingdoms. Political instability in the north caused a large migration of Chinese people to the Yangtze River basin. This caused the people living in this area to move to the relatively wild and uncharted south, where various tribal peoples were already living. This started a process of colonization of indigenous lands by the Han Chinese that continues to this day. Some indigenous peoples mixed with the recently-arrived Chinese, assimilating into the Han Chinese masses. Others, such as the Yao, maintained their independence. However, they were forced to abandon their most fertile lands, and migrate further south and into the mountains to agriculturally less productive areas.

Mongols are one of the largest minorities in China, concentrated especially in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region.Most ethnic Uighurs live in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Beginning in the Han dynasty, Han Chinese fought for hegemony along the Yili and Tarim caravan routes through this region, but it was not until the Qing dynasty that the area was fully incorporated into the Chinese state. Uyghurs speak a Turkish language and most are Muslim. Most Tibetans live on the Tibetan Plateau, which includes Qinghai province as well as the Tibetan Autonomous Province. Among ethnic minorities, women's and children's clothing and hairstyle often seems to diverge more from Han customs than men's do.

Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: To some extent, the current classification of nationalities follows categories and terms in use in the literature during the Republican period or earlier. In some cases, the written form of the name has been changed to a neutral one; formerly, the names of many groups were written with a “dog" radical or a character that carried a derogatory meaning while representing the pronunciation of the name. In other instances, the group's own choice of ethnonym has been substituted for the former Chinese term of reference. By the early 1980s, the National Minorities Commission had revised and standardized the names. They were assisted in this by local cadres and by ethnologists from the minority institutes, universities, and academies of social science.

Chinese Minority Groups Under the Communists

In the 1950s, the Minzu Shibie (minorities identification project)—the first major work of ethnic identification in China—was carried and for the most part the 56 or so ethnic groups recognized were defined and categorized. Most of the designations are reasonable and logical and are based on linguistic, historical and cultural criteria. But in some cases—especially with small, difficult-to-categorize groups—groups that were different in many respects were grouped together (See the Nu minority) and small groups were thrown in with larger groups because it seemed they didn’t justify the trouble of designating them as a separate ethnic group. During the Cultural Revolution all religious practices were banned. Harsh punishments were inflicted on those who were caught practicing their faith.

In the 1950s, the Minzu Shibie (minorities identification project)—the first major work of ethnic identification in China—was carried and for the most part the 56 or so ethnic groups recognized were defined and categorized. Most of the designations are reasonable and logical and are based on linguistic, historical and cultural criteria. But in some cases—especially with small, difficult-to-categorize groups—groups that were different in many respects were grouped together (See the Nu minority) and small groups were thrown in with larger groups because it seemed they didn’t justify the trouble of designating them as a separate ethnic group. During the Cultural Revolution all religious practices were banned. Harsh punishments were inflicted on those who were caught practicing their faith.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ One could argue that since 1949 some of the earlier differences between local cultures or nationalities have weakened or disappeared. This occurrence is a result of a number offactors: the spread of Mandarin as the language of the schools and media; the uniform political and social ideology promoted via the Communist party, the Youth League, the Women's Federation, the Peasants Association, and the Peoples Liberation Army; nationwide participation in a series of political campaigns; state control of the news and entertainment media; and the uniformity of socioeconomic organization between 1950 and the early 1980s. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Furthermore, the suppression of some local religious practices and the development of secularized, state-revised festivals and state guidelines for betrothals, weddings, and funerals have all contributed to the blurring of the differences between regional Han cultures, and they have also had their effect on the practices of the minorities. Over recent decades, population movements have also played a part. Han families from diverse regions have been resettled in large numbers in newly developing areas such as the northeastern provinces, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia, whereas some minority communities have been relocated closer to Han areas of settlement. During the Cultural Revolution years this process was accelerated by the transfer of at least 12 million young Han urbanites to rural villages and state farms, some of these in areas primarily inhabited by the ethnic minorities. Many of these transfers have become permanent.

Since the 1980s there has been population movement from the countryside into established urban areas, both by assignment and voluntarily, heavy immigration into the new Special Economic Zones and Development Zones, and a flow into underpopulated areas that hold promise of economic opportunity. Despite these unifying trends, there are also signs of intensification of ethnic awareness and sentiment among the minorities. Some of the official classifications have taken on new meaning. This development is clearly evident in the 1990 census, which reports a large jump in the number ofindividuals or communities claiming minority status.

Communist Party Take on Chinese Minority History

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “When it comes to China’s ethnic minorities, the party-run history machine is especially single-minded in its effort to promote story lines that portray Uyghurs, Mongolians, Tibetans and other groups as contented members of an extended family whose traditional homelands have long been part of the Chinese nation. Alternate narratives are far less cheery. They include tales of subjugation and repression amid government-backed efforts to dilute ethnic identity through the migration of members of China’s dominant group, the Han. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, August 18, 2014 ~~]

“Chinese historians rarely veer from the officially sanctioned scripts; Uyghur and Tibetan scholars who have insisted on writing about the disagreeable aspects of Communist rule have seen their books banned and their careers destroyed. James A. Millward, a professor at Georgetown University who studies China’s ethnically diverse borderlands, said the drive to shape history, while not unique to China, was zealously practiced by each succeeding dynasty in an effort to malign an emperor’s predecessors and glorify his own rule. ~~

“But the Communists have also sought to use history as a tool against separatist aspirations and to legitimize their efforts to govern potentially restive populations. “The ability to control historical narratives and airbrush out problematic truths is a powerful tool but it also reveals the party’s insecurity over certain aspects of the past it would rather the world forget,” Professor Millward said. ~~

“Party propagandists have been especially drawn to female protagonists, often royal consorts, who were bit players in grand power struggles involving warring states on the fringes of the ancient Chinese empire. In Inner Mongolia, the vast grasslands that form a buffer between China and Mongolia, it is Wang Zhaojun, a lovelorn Han dynasty consort who supposedly offered herself to a “barbarian” Mongolian prince to cement an alliance between the two peoples. ~~

Assimilation, Han Cultural Forces and Minorities in China

Dongxiang child Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ “Over the centuries many ethnic groups have been absorbed into the Han majority, especially in the south and west. Sichuan has always had many ethnic groups, but today the large majority are Han Chinese. The majority of ethnic minorities today live in the northeast, northwest, and southwest, undoubtedly as a consequence of the expansion of the Han Chinese over the centuries. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington /=]

Entry into Han society has not demanded religious conversion or formal initiation. It has depended on command of the Chinese written language and evidence of adherence to Chinese values and customs. For the most part, what has distinguished those groups that have been assimilated from those that have not has been the suitability of their environment for Han agriculture. People living in areas where Chinese-style agriculture is feasible have either been displaced or assimilated. [Source: Library of Congress]

The consequence is that most of China's minorities inhabit extensive tracts of land unsuited for Han-style agriculture; they are not usually found as long-term inhabitants of Chinese cities or in close proximity to most Han villages. Those living on steppes, near desert oases, or in high mountains, and dependent on pastoral nomadism or shifting cultivation, have retained their ethnic distinctiveness outside Han society. The sharpest ethnic boundary has been between the Han and the steppe pastoralists, a boundary sharpened by centuries of conflict and cycles of conquest and subjugation. Reminders of these differences are the absence of dairy products from the otherwise extensive repertoire of Han cuisine and the distaste most Chinese feel for such typical steppe specialties as tea laced with butter.

Jonathan Kaiman and Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: In recent decades " a variety of social, economic and political forces have pushed them toward assimilation into mainstream Chinese culture. The lure of well-paid work in the cities draws young people away from traditional village life. Television and popular music have eclipsed traditional forms of entertainment.” [Source: Jonathan Kaiman and Andrew Jacobs , New York Times July 16, 2011]

In a review of “Reconfiguring Class, Gender, Ethnicity and Ethics in Chinese Internet Culture”, Jamie J. Zhao wrote: While recognizing the hegemonic status of Mandarin in mainland China, Gong and Yang pay particular attention to online non-Han ethnic practices that are expressed in Mandarin Chinese. Various intriguing examples are examined: Tibetan writer Woeser’s online writing and her hybrid (ethnically mixed) Tibetan-ness; a set of self-exoticized Tibetan wedding photos that became a sensation on the Chinese Internet in 2015; and an online-circulated ethnic flash mob at Tibet University, etc. The authors argue that the use of Internet and digital media plays a prominent role in complicating already self-conflicted non-Han ethnic cultures and voices. On the one hand, the performativity of minzu looms large online, which enables the subjective, mediated self-expression of ethnic minorities. On the other hand, it also reveals ethnic minorities’ (either willing or involuntary) assimilation into and compromise with postsocialist consumerist Han culture. Ultimately, this convergence of the Internet and minzu exposes the artificiality, contingency, and contradiction of the imagined, simplistic binary of modern Han Chinese and traditional, if not primitive, non-Han Chinese cultures. [Source:“Reconfiguring Class, Gender, Ethnicity and Ethics in Chinese Internet Culture” by Haoming Gong and Xin Yang (Routledge, 2017) Reviewed by Jamie J. Zhao, MCLC Resource Center Publication, September, 2017]

See Separate Article DIVERSITY, ASSIMILATION AND ETHNIC RELATIONS AND TENSIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Cultural Diversity Within the Han Chinese

The peoples identified as Han comprise 91 percent of the population, from Beijing in the north to Canton in the south, and include the Hakka, Fujianese, Cantonese and others. These Han are thought to be united by a common history, culture and written language; differences in language, dress, diet and customs are regarded as minor. An active, state-sponsored program assists the official minority cultures and promotes their economic development (with mixed results). [Source: By Dru C. Gladney, Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2009, Dru Gladney is president of the Pacific Basin Institute at Pomona College]

Cultural diversity within the Han has not been officially recognized because of a deep (and well-founded) fear of the country breaking up into feuding kingdoms, as happened in the 1910s and 1920s. China has historically been divided along north-south lines, into Five Kingdoms, Warring States or local satrapies, as often as it has been united. Indeed, China as it currently exists, including large pieces of territory occupied by Mongols, Turkic peoples, Tibetans, etc., is three times as large as it was under the last Chinese dynasty, the Ming, which fell in 1644. A strong, centralizing government (whether of foreign or internal origin) has often tried to impose ritualistic, linguistic, economic and political uniformity throughout its borders.

See Cultural Diversity Within the Han Chinese Under HAN CHINESE AND THE PEOPLE OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

Ethnic Revival in China

Dong during Autumn Festival

Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: Some groups have had a dramatic rise in population since the 1982 census, most markedly the Manchu, Tujia, She, Gelao, Xibe, Hezhen, Mulam, and those claiming Russian nationality. There is increased demand for school texts and other publications in minority languages (including tongues formerly classed as 'dialects"), with recognized standardized romanizations or reformed versions of earlier traditional writing systems. With these come demands for separate schools at the primary level, and the recognition of additional autonomous counties or townships in areas with large minority populations. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Among many groups there is revival, elaboration, or even invention of local dress and other visible markers of ethnic difference. There is also increased production of local craft items (or items with a minority 'feel" to them) for a wider market, as well as a revitalization of local festivals. Some of these changes relate to the growing international and internal tourist market, as at the Dai Water-Splashing Festival in Xishuangbanna, the Miao Dragon Boat Festival in eastern Guizhou, or the tourist souvenirs and entertainment provided by the Sani (Yi) at the Stone Forest near Kunming.

Among the Hui and other Islamic groups, religion has been revitalized and is tolerated by the state because of its desire to maintain and increase good foreign relations with Islamic countries. Buddhism among the Dai and Christianity among the Miao, Yi, Lisu, Lahu-and, of course, the Han themselves-are tolerated for similar reasons. The state allows and in some ways even encourages the upsurge of ethnic expression, as long as it does not move toward separatism. China takes pride in describing itself as a multinational country.

Minority themes figure strongly in contemporary Chinese painting and graphics, and television frequently airs travelogues and commentaries about the minorities and performances by song-and-dance ensembles whose material is drawn in large part from the minority cultures. Books about the strange customs of the shaoshu minzu find a wide market; occasionally, they also spark protests by the minorities.

Foreign NGOs and Preserving Minority Languages in China

Up to 40 percent of China’s minority languages may be at risk of extinction. Phonemica, a project aiming to document China’s threatened languages and dialects through stories told by native speakers, is currently raising funds through indiegogo, a small group of linguists (and a growing group of volunteers) that believe that there is tremendous value in documenting China’s rapidly disappearing languages and dialects. Phonemica is a project to do exactly that. The group is building an open archive of stories from people all over China and the Chinese diaspora, told in the everyday speech of their home towns. [Source: Samuel Wade, China Digital Times, May 6, 2013]

Studying diversity in language helps us understand diversity in culture and how we exist as societies. Sadly, much of China’s linguistic diversity is being threatened by ever-growing pressure from Standard Mandarin. As a result, fewer people are teaching their mother tongues to their children. One consequence of this is that we’re quickly approaching a point where children cannot communicate with their grandparents, whose stories will then be lost. The academic side is that, with this loss of linguistic diversity, we are losing opportunities to understand how these languages work, giving us that much less to help us understand how language as a whole works.

The Eastern Tibet Training Center (EETI) is a vocational training school in Shangri-La (Zongdian) in Yunnan Province where Tibetans, Naxi, Bai, Han and Yi from rural villages are taught English, computer skills and other things in a 16-week, live-in, fully-funded program. The founder of the school, Ben Hillam, a professor at Australian Nation University specializing in development in China, told National Geographic, the ‘school is designed to help students from rural areas bridge the gap to urban job opportunities...They are traditionally agropastorialists, experts at subsistence farming — growing barley, raising yaks and pigs. But these aren’t the skills that youth need today...Culture is something that constantly evolves...Economic development can rekindle interest in cultural heritage, which is inevitably reinterpreted.”

European Chinese and Other Foreigners in China

There are a few European-looking Chinese but not many. Xu Xiangshun is a 58-year-old Italian-born Chinese peasant. He has European features and aquamarine eyes, speaks only a local Chinese dialect and chains smokes and spits like any ordinary Chinese man. Xu was born to Italian parents. His father was killed in World War II and his mother married a Chinese man named Wu and moved with him to China.

Xu’s mother died soon after they arrived in China. Xu dropped out of school in second grade because he was teased so much over his looks by the other students and never learned to read or write. He became a peasant farmer, married a Chinese woman and had three children. He finally got a chance to return to Italy in the late 1990s. By that time he’d long forgotten his Italian name.

According to the 2010 census some people were classified as: 1) Undistinguished 0.0480 percent of the population: 640,101 in 2010, 734,438 in 2000, 749 341 in 1990; and 2) Naturalized Citizen: 0.0001 percent; 1,448 in 2010, 941 in 2000, 3,421in 1990. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

A Vietnamese Chinese in Guangdong Province told the Washington Post. “The government doesn’t help us mainly because we are Chinese Vietnamese. We are poor and uneducated, so no one in our group works for the government. The government knows we are a weak group.”

Image Sources: Wikicommons; Maps: University of Washington; Posters, Landsberger Posters;

Text Sources: "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: China, Russia and Eurasia" edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company); Wong How-Man, National Geographic, March 1984; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022