EDUCATION IN TIBET

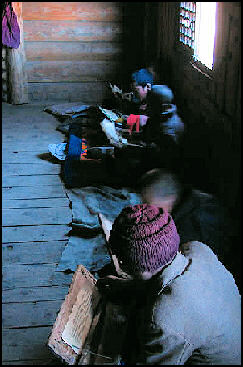

Students studying a monastery

The Communist Chinese have greatly improved education in Tibet. They have built hundreds of schools. Before their arrival there were only a handful of non-religious schools on Tibet. Only a small minority received any kind of education at all. A census in 2010 found that people living in Tibet were better educated than in 2000. The number of college graduates per 100,000 residents rose from 1,282 to 5,507 in that time and at least 17,200 out of every 100,000 finished secondary school, as opposed to 9,891 in 2000. [Source: Xinhua, May 4, 2011]

Education was once reserved for monks in monasteries. Layperople that were educated were often done so by monks. Since the Communists came to power in China 1949, an educational system from primary school to university has been created in Tibet and Qinghai practically from scratch. It includes medical and technical schools. However, many people live in remote areas and it is hard for them to travel to a school. Many young Tibetans head to the cities to study.

According to the Chinese government: “Education in the Tibetan areas used to be monopolized by the monasteries. Some of the lamas in big lamaseries, who had learned to read and write and recite Buddhist scriptures and who had passed the test of catechism in the Buddhist doctrine, would be given the degree of Gexi, the equivalent of the doctoral degree in theology. Others, after a period of training, would be qualified to serve as religious officials or preside over religious rites. [Source: China.org]

When the Chinese arrived in in 1950 there were no universities in Tibet. Three institutions of higher learning had opened by the end of 1985 as well as 2,600 middle and primary schools, with a total enrollment 87 per cent more than in 1965. Many Tibetan professors, engineers, doctors, veterinarians, agronomists, accountants, journalists, writers and artists have been trained." For a long a time Tibetan language and customs and habits were respected and many classes were taught in Tibetan but that is no longer the case (See Below) . For the most part, Tibet has been closed to Western scholars and researchers. In many cases, the work of Chinese scholars has also been curtailed. [Source: China.org]

See Separate Articles: GOVERNMENT OF TIBET: CHINESE CONTROL, TRADITIONAL RULE AND THE CTA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE GOVERNMENT POLICY AND DEVELOPMENT IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; articles under TIBETAN GOVERNMENT, SERVICES AND ECONOMICS factsanddetails.com

Sources on Education in China:

Sources on Education in China: Tashi Ragbey (trabgey@gwu.edu), co-founder of the non-profit Machik (http://www.machik.org/), which works with Tibetan youth on language and cultural education. You can find a wealth of information, and many more worthwhile citations, in Naomi Furnish Yamada's PhD dissertation, which is on contemporary minority education and with lots on Tibetan areas: There is a detailed account about education in Tibet written by Martina Wernsdörfer, but it is in German only: Experiment Tibet. Felder und Akteure auf dem Schachbrett der Bildung. Peter Lang. Books by scholars like Matthew Kapstein, Melvyn Goldstein, Gray Tuttle, and many others.

Books and Studies: A) “Education in Tibet: Policy and Practice Since 1950" by Catriona Bass, St. Martin's Press, 1998; B) “Anthropological Field Survey on Basic Education Development in the Tibetan Nomadic Community of Maqu, Gansu, China” by Lopsang Gelek, Asian Ethnicity 7(1), February 2006; C) “Schooling Sharkhog,” by Janet Upton, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, 1999, (also see other work by Janet Upton; "Education in Rural Tibet” by Gerard Postiglione, Ben Jiao and Sonam Gyatso, 2005; D) “Education and social change in China: inequality in a market economy, “ Gerard A. Postiglione, editor ; foreword by Stanley Rosen, M.E. Sharpe, 2006; E) “Choosing Between Ethnic and Chinese Citizenship: the educational trajectories of Tibetan Minority Children in Northwestern China” by Lin Yi; F) “Chinese Citizenship: Views from the Margins” by Rachel Murphy and Vanessa L. Fong (eds), Routledge.

G) “Teaching and learning in Tibet: A review of research and policy publications” by Ellen Bangsbo; Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, Copenhagen: NIAS; London: Taylor & Francis 2004; H) “On the margins of Tibet: Cultural survival on the Sino-Tibetan frontier. By Ashild Kolas; Monika P Thowsen. Seattle; London: University of Washington Press, 2005; “Education as tautology: Disparities, preferential policy measures and preparatory programs in Northwest China: Naomi C.F. Yamada, University of Hawai'i at Manoa, 2012. ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing. 3534561.

On education in Tibet: in the general literature on Tibet, you would also find a large literature on Tibetan education before the Chinese, and that includes education in language, religion-Buddhism, philosophy, medicine etc etc, that has been partially revived after Mao. (Buddhism is all about "teaching" and "learning". There used to be a "Tibet Film and Video List" online, compiled by Tom Grunfeld, with 800+ titles. But I can't find it now? However, this list seems to also list films about schools, etc.: http://tibetsites.com/articles/10-Videos-and-Films-on-Tibet.html [Source: Magnus Fiskesjö, Cornell]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Education in Tibet: Policy and Practice since 1950" by Catriona Bass Amazon.com; “The Struggle for Education in Modern Tibet: The Three Thousand Children of Tashi Tsering” by William R. Siebenschuh and Tashi Tsering Amazon.com; “Series of Basic Information of Tibet of China -- Tibetan Education” by Zhou Aiming Amazon.com; “An Introduction to Ethnic Minority Education in China: Policies and Practices” by Sude, Mei Yuan, et al. Amazon.com ; “Minority Languages, Education and Communities in China” by L. Tsung Amazon.com; “China's National Minority Education: Culture, Schooling, and Development” by Gerard A. Postiglione Amazon.com; “Language, Culture, and Identity among Minority Students in China: The Case of the Hui’by Yuxiang Wang Amazon.com ; “Minority Education in China: Balancing Unity and Diversity in an Era of Critical Pluralism” by James Leibold and Yangbin Chen Amazon.com

Illiteracy and Poor Education in Tibet

Tibet has highest illiteracy rate in China. According to Statista the illiteracy rate in Tibet in 2020 was 28 percent, the highest in China by a large margin, compared with a national average of 3.26 percent in China. The second lowest was Qinghai, which has a large Tibetan population, at around 10 percent. Tibet's rate is an improvement from 42 percent in 2000. According to the 1990 census, 72.8 percent of ethnic Tibetans over the age of 15 were illiterate. In the 1950s the figure was 95 percent.

Lack of a good formal education has long been a major social problems in Tibet. It is hard to provide good education for Tibet's small population, which is scattered over such a large area of land. Many Tibetans are held back by a lack of education. A surprising number can’t read or write, speak Chinese or do basic math. Those that work in markets often rely on intermediaries, often Muslim Huis, to do the calculating, weighing and marketing of their products in markets.

In the 2000s, only 78 percent of Tibetan children entered elementary school and only 35 percent entered middle school. Although even the poorest families consider education to be of utmost importance, many families can't send their children to school because schools are in short supply and children are needed for agricultural and herding chores. Poor families that value education often spend what little money they have for education on one child. The others often can not read to write.

Education in Tibet in the Early 2000s

According to the Chinese government: A Plan for Compulsory Education in the Tibet Autonomous Region was adopted in 1994. In 2005, the teaching and administrative staff reached 22,279, among whom 19,276 are full-time teachers, and the teachers of ethnic minorities, with most being Tibetans, account for some 80 percent. [Source: chinaculture.org, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China, October 10 2005]

According to statistics, Tibet had 820 primary schools, 101 middle schools and 3,033 teaching centers, with a total enrollment of 354,644 in primary and middle schools, including 34,756 junior middle school students and 9,451 senior middle school students in Tibet in 2005. The enrollment ratio of school-age children has reached 83.4 percent.

In 2005, compulsory education comprised three in pastoral areas; six years in agricultural areas; and nine years in major cities and towns. Sixteen secondary vocational schools had been set up in the region, and the number of Tibetan students attending such schools both within and outside Tibet has reached 8,161. With the development of adult education, the illiteracy rate of Tibetan young and middle-aged people declined from 95 percent before 1951 to 42 percent in 1999.Higher education has also been developed rapidly. Tibet has now established four universities — the Tibet Ethnic Institute, Tibet Institute of Agriculture and Animal Husbandry, Tibet University, and Tibet College of Tibetan Medicine, with a total enrollment of 5,249.

Between 1985 and 2005 over 20,000 students have graduated from universities, and more than 23,000 from secondary vocational schools. Some Tibetans have received master's degrees or doctorates. A large number of Tibetan professionals have thus been trained, including scientists, engineers, professors, doctors, writers and artists.

Modernizing Tibetan Education

Tim Sullivan of Associated Press wrote: “In Tibetan culture, change has traditionally come at a glacial pace. Isolated for centuries atop the high Himalayan plateau, and refusing entry to nearly all outsiders, Tibet long saw little of value in modernity. Education was almost completely limited to monastic schools. Magic and mysticism were — and are — important parts of life to many people. New technologies were something to be feared: Eyeglasses were largely forbidden until well into the 20th century. No longer. Pushed by the Dalai Lama, a fierce proponent of modern schooling, a series of programs were created in exile to teach scientific education to monks, the traditional core of Tibetan culture. [Source: Tim Sullivan, Associated Press, July 3, 2012 ^/^]

“The Tibetan culture, meanwhile, is increasingly imperiled. Ethnic Han Chinese, encouraged by generous government subsidies, now outnumber Tibetans in much of Tibet. The traditional Tibetan herding culture is dying out as people move to cities. Many young Tibetans now speak a tangle of Chinese and Tibetan. Amid such tumult, the Dalai Lama — a man raised to live in regal isolation as a near-deity — has instead spent much of his life seeking ways that Tibetans can hold onto their traditions even as they find their way in the modern world. He has encouraged modern schooling for exile children. There are job programs for the armies of unemployed young people.” ^/^

Monastery Education in Tibet

Education has traditionally been centered in the monasteries in Tibet. Traditional monastery schools today provide religious training, teach reading, writing, math and sciences and provide training in the arts, crafts and professions. Instruction is provided by religious teachers called "dge bshe." After entering the school monk initiates are divided into groups and spend 10 years memorizing texts, debating a variety topics, studying, learning how to conduct ceremonies and taking exams. Oracles, mediums and exorcists receive special training.

One Tibetan teacher told National Geographic, “One of the main reasons Tibet is so backward is that too many men were in the monasteries and not contributing toward development. I continually advise parents to send their children to school not to monasteries. Otherwise the economy will remain stagnant, and we’ll never be able to compete economically.” Some have suggested that boys at any age should be allowed to enter monasteries but that the monasteries have to provide a Chinese education. Tibetan families pay monasteries as little as $30 a month to teach a boy or girl Tibetan, Chinese, a little English and math.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times:“Monasteries have long served as educational institutions in Tibetan society, with monks and nuns among the elite few who could read and write before Tibet came under Chinese Communist rule in 1951. Until recently, many monasteries held classes on the written language for ordinary people, and monks often gave lessons while traveling. “Mr. Tashi said he first learned to read and write Tibetan in primary school and from older brothers who had studied with a monk. He continued studying as a monk himself for three years, and in 2012, he took private classes in Yushu for a few months. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 28, 2015]

See Studying and Debating Monks Under TIBETAN BUDDHIST MONKS factsanddetails.com

Schools in Tibet

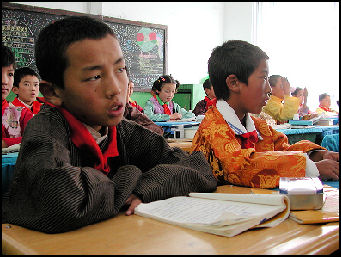

Tibetan kids in a Chinese-run schoolThe Chinese have built an education system virtually from scratch in Tibet. In 1951, there were no public schools in Tibet By 1999, there were over 2000.

Unlike schools outside of Tibet, elementary schools and middle schools in Tibet charge no tuition fees. High schools charge about $70 a semester, including board. The government goes through great lengths to encourage Tibetan students to stay in school. Free transportation is offered to children of nomads.

Many Tibetan cities and towns have new schools with facilities that are much better than their counterparts in provincial China. The situation is different in the Tibetan countryside. In some poor rural schools, many classes are conducted standing up because there are no chairs in the classrooms. In others, children have no pencils and they sit on cement floors to save wear and tear on their desks. Teachers in these schools receive lass than $1 a month for school supplies. In some places the schools are only in session when inspectors are around.

Students are discouraged from engaging in any kind of religious activity. In some schools, Tibetan children are forced to say things like "I am a Chinese citizen” and that Tibet is a land of savages and that Tibetan Buddhism is a superstition.

Elementary school students are taught the importance of achieving a per capita GNP of a developed country by 2050 and told: "We must achieve the goal of modern socialist construction...We must oppose the freedom of the capitalist class, and we must be vigilant against the conspiracy to make a peaceful evolution towards imperialism."

The curriculum in exile schools in India and elsewhere highlights Tibetan suffering at the hands of Chinese

Chinese-Run School in Tibet

“The government has encouraged wealthier Chinese cities to finance school construction in Tibet. In the city of Shigatse, four hours from Lhasa, the Tibet-Shanghai Experimental School was completed in 2005 with an investment of $8.6 million from the Shanghai government. The principal, Huang Yongdong, arrived in January from Shanghai for a three-year posting. Nearly 1,500 students, all Tibetan, attend junior and senior high schools here. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, July 24, 2010]

“A portrait of Mao hangs in the lobby. All classes are taught in Mandarin Chinese, except for Tibetan language classes. Critics of the government ethnic policies say the education system in Tibet is destroying Tibetans’ fluency in their own language, but officials insist that students need to master Chinese to be competitive. Some students accept that.”

“My favorite class is Tibetan because we speak Tibetan at home,” said Gesang Danda, 13. “But our country mother tongue is Chinese, so we study in Chinese.” On a blackboard in one classroom, someone had drawn in chalk a red flag with a hammer and sickle. Written next to it was a slogan in Chinese and Tibetan: "Without the Communist Party, there would be no new China, and certainly no new Tibet."

Schools and Language in Tibet

Schools in Tibet often have separate classes for Tibetan and Chinese children. This is done mainly for linguistic reasons, with the Han Chinese receiving instruction in their language and, for a long time, Tibetans being taught in Tibetan. Until around the early 2010s, many Tibetan students took courses in Tibetan and Chinese while Chinese students take Chinese and English. These many Tibetans take all their classes in Chinese.

In the 2010s, 90 percent of school lessons in Tibet were in Chinese. For the remainder, students could choose between Tibetan and English. An envoy of the Tibetan government-in-exile Dawa Tsering told a forum in Taipei organized by the Taiwan New Century Foundation: “Take me: I don't speak Tibetan very well, even though I grew up in Tibet and my parents speak only Tibetan. That's because I attended elementary school during the Cultural Revolution and the Tibetan language was not allowed in school,’ Dawa said, adding that although Tibetan language instruction was later permitted, it was more for ‘cosmetic’ purposes. He added, “A civilization that loses its language becomes one that is only good for display in a museum. “

Tibetan students are encouraged to learn Chinese because they need to know the language if they want to do well on the all-important university entrance exam, gain admission to a university, get a good job and generally get ahead in life in China and Chinese-controlled Tibet. One 17-year-old Tibetan in Shigatse told the Washington Post, “I use Tibetan at home, but I use Chinese with my friends. My teacher said that is the best way. Now my Chinese is better than my Tibetan. That’s the future.” A Tibetan student told Reuters, “I want to be a lawyer and for me Chinese plays a very important role both in my life and my study...If someone can’t speak Chinese then they might as well be mute.”

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “Tibetan attitudes" about language "are complicated by the practical reality of living in a country where the Chinese language is dominant, and where parents and children sometimes prefer English as a second language of education, not a minority language. Some Tibetan parents worry that their native language and culture are dying but nevertheless tell their children to prioritize Chinese studies, in part because the national university entrance exam is administered only in Chinese. “The parents think that Chinese is most important for their children’s future,” said Phuntsok, a monk at a Yushu monastery told by officials to close its Tibetan classes this year.The government says it supports bilingual education. In practice, though, bilingual education now generally means using Chinese as the main language of instruction, while a minority language is taught as a separate subject. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 28, 2015]

Tibetan children in exile study in Tibetan until they are 10 so they are rooted in their culture and then switch to English.

See Separate Article TIBETAN LANGUAGE: GRAMMAR, DIALECTS, THREATS AND NAMES factsanddetails.com ; See Chinese Replacing the Mongolian Language in Inner Mongolia Schools and Protests Under MONGOL ISSUES, ANGER, ACTIVISM AND PROTESTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Replacing Tibetan Language with Chinese at Tibetan Schools

Chinese has displaced Tibetan as the main teaching medium in schools despite the existence of laws aimed at preserving the languages of minorities. Young Tibetan children used to have most of their classes taught in Tibetan. They began studying Chinese in the third grade. When they reached middle school, Chinese becomes the main language of instruction. An experimental high school where the classes were taught in Tibetan was closed down. In schools that are technically bilingual, the only classes entirely taught in Tibetan were Tibetan language classes. These schools have largely disappeared.

These days many schools in Tibet have no Tibetan instruction at all and children begin learning Chinese in kindergarten. There are no textbooks in Tibetan for subjects like history, mathematics or science and tests have to be written in Chinese. Tsering Woeser, a Tibetan writer in Beijing, told the New York Times that when she lived” in 2014" in Lhasa, she stayed by a kindergarten that promoted bilingual education. She could hear the children reading aloud and singing songs every day — in Chinese only. Most Han Chinese teachers know little or no Tibetan. They teach their classes either in Chinese or English. At one school a Chinese principal who didn't speak one word of Tibetan told the Washington Post, "Tibetans don't have a vocabulary for science. Some science terms that are two words in Chinese, like 'electrical resistance,' when you translate then into Tibetan come up with a whole long string that you can't even write on the blackboard." Tibetan middle school and high school teachers are supposed to teach in Mandarin although many teach in Tibetan.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times:“Many schools in” Tibetan areas in Qinhai and Sichuan — home “to nearly 60 percent of China’s Tibetan population — had taught mainly in the Tibetan language for decades, especially in the countryside. Chinese was taught too, but sometimes not until later grades. “This is why almost all innovation in Tibetan literature, film, poetry and so forth, plus a great deal of academic writing, since the 1980s has come from Qinghai,” said Robbie J. Barnett, a historian of Tibet at Columbia University. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 28, 2015]

“But in 2012, officials in Qinghai and neighboring Gansu Province introduced a teaching system that all but eliminated Tibetan as a language of instruction in primary and secondary schools. They had backed off a similar plan in 2010 because of protests by students and teachers across Qinghai and Gansu, and even in Beijing. Schools were ordered to use Chinese as the main language of instruction, which led to layoffs of Tibetan teachers with weak Chinese-language skills. And new Chinese-language textbooks were adopted that critics said lacked detailed material on Tibetan history or culture.

“The Chinese Constitution promises autonomy in ethnic regions and says local governments there should use the languages in common use. In 1987, the Tibetan Autonomous Region, which encompasses central Tibet, published more explicit regulations calling for Tibetan to be the main language in schools, government offices and shops. But those regulations were eliminated in 2002. These days, across Tibetan areas, official affairs are conducted mostly in Chinese, and it is common to see banners promoting the use of Chinese. Such efforts are in part a response to the Tibetan uprising in 2008, when anti-government rioting broke out in Lhasa and spread across the plateau. “The government thinks people who go to ethnic schools have a stronger Tibetan nationalist identity,” Ms. Woeser said. “The government thinks if they switch the instruction to Chinese, then people will change their views.”

Closing Schools That Teach Tibetan

Reporting from Yushu in Qinghai Province, Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: When officials forced an informal school run by monks near here to stop offering language classes for laypeople, Tashi Wangchuk looked for a place where his two teenage nieces could continue studying Tibetan. To his surprise, he could not find one, even though nearly everyone living in this market town on the Tibetan plateau here is Tibetan. Officials had also ordered other monasteries and a private school in the area not to teach the language to laypeople. And public schools had dropped true bilingual education in Chinese and Tibetan, teaching Tibetan only in a single class, like a foreign language, if they taught it at all. “This directly harms the culture of Tibetans,” said Mr. Tashi, 30, a shopkeeper who is trying to file a lawsuit to compel the authorities to provide more Tibetan education. “Our people’s culture is fading and being wiped out.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 28, 2015]

“China has sharply scaled back, and restricted, the teaching of languages spoken by ethnic minorities in its vast western regions in recent years, promoting instruction in Chinese instead as part of a broad push to encourage the assimilation of Tibetans, Uighurs and other ethnic minorities into the dominant ethnic Han culture. The Education Ministry says a goal is to “make sure that minority students master and use the basic common language.” And some parents have welcomed the new emphasis on teaching Chinese because they believe it will better prepare their children to compete for jobs in the Chinese economy and for places at Chinese universities.

“Monasteries have long served as educational institutions in Tibetan society. But in the mid 2010s, officials in many parts of the plateau have ordered monasteries to end the classes, though Tibetan can still be taught to young monks. “Mr. Tashi said “My nieces want to become fluent in Tibetan but don’t know where to go. Our words will be lost to them.”

Resentment Over the Decline of Teaching Tibetan in Schools

Reporting from Yushu in Qinghai Province, Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “But the new measures have also stirred anxiety and fueled resentment, with residents arguing that they threaten the survival of ethnic identities and traditions already under pressure by migration, economic change and the repressive policies of a government fearful of ethnic separatism. The shift away from teaching Tibetan has been especially contentious. It is most noticeable outside central Tibet, in places like Yushu, about 420 miles northeast of Lhasa, in Qinghai Province.[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 28, 2015]

“In March 2012, a student in Gansu, Tsering Kyi, 20, set fire to herself and died after her high school changed its main language to Chinese, her relatives said. She is one of more than 140 Tibetans who since 2009 have self-immolated in political protest. Three years later, frustrated students are still taking to the streets. In March, high school students marched in Huangnan Prefecture in Qinghai. The local government accused the Dalai Lama, the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader, and “hostile Western forces” of tricking students to “defy the law, disrupt society, sabotage harmony and subvert the government.”

In November 2015, a petition circulated on WeChat, the Chinese messaging app, calling on officials to open a Tibetan-language primary school in Qinghai’s provincial capital, Xining, which has had no such schools under Communist rule. “Letting 30,000 Tibetan children learn their mother tongue so they can carry on their own traditional culture is a very important matter,” said the petition, which got more than 61,000 signatures before censors blocked it.

Tibetan Children Banned From Taking Tibetan Language Classes Outside of School

In November 2021, Radio Free Asia reported that children in the northwestern province of Qinghai, which was historically part of Tibet’s Amdo region, the birthplace of the 14th Dalai Lama, were banned from even taking informal lessons Tibetan language outside of school. Nextshark reported: In recent years, the province has seen a growth in Tibetans and a decline in Han Chinese populations, according to census data. “No individual or organization is allowed to hold informal classes or workshops to teach the Tibetan language during the winter holidays when the schools are closed,” a Tibetan living in Qinghai told Radio Free Asia. “This is an attempt to wipe out the Tibetan language.” “Violators of the ban will face “serious legal consequences and punishment,” the source said. [Source: Carl Samson, Nextshark, November 10, 2021]

This leaves the Tibetan language being taught only in government-run schools, which have begun the work to teach all other subjects in Chinese. In September 2021, China released its National Program for Child Development, which left out a previous pledge to “respect and protect the rights of children of ethnic minorities to be educated in their own language,” as per VOA News. Authorities reportedly changed the wording to “promoting the common national language,” leaving ethnic minority children with no choice but to learn in Chinese instead of their native language.

“The policy begins as early as kindergarten, according to a decree sent earlier in July. By requiring Mandarin as the medium of instruction in kindergarten schools, authorities expect to see “a community for the Chinese nation from an early age.” “The plan is designed to weaken the child’s grasp of one’s mother tongue in the first few years,” Tenzin Sangmo, a researcher with the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy (TCHRD), told Phayul. “Although studies have shown that children are capable of picking up more than one language in early years and much rest in the hands of parents, we must remember that the imposition of compulsory Mandarin education in this context would serve as a conduit for sinicization lessons and cultural values that come with the introduction of a language.”

“Tibetan parents, locals and rights activists have all expressed concerns over the policies, but the Chinese government remains firm. In August 2021, a teenager was reportedly arrested after petitioning to have the Tibetan language prioritized in school, Phayul reported.

Chinese-Supported School Teaching Tibetan Ways

Reporting from Zhandetan in Qinghai Province, Dan Levin wrote in New York Times, “There are many marvels at the end of the punishing dirt road that skirts the edge of this stark white glacier high on the Tibetan plateau: thousands of fluttering crimson prayer flags, planted on the slopes by the religious faithful; wild goats scrambling across impossibly steep cliffs; and Buddhist monks meditating as they have for centuries in a place where newcomers find themselves gasping for air. But perhaps the greatest marvel unfolds each morning in the newly built classrooms here at the foot of one of Tibetan Buddhism’s holiest mountains — six hours from the nearest city and far from the circumspect eyes of Communist Party technocrats — where dozens of young men and boys learn to write the curlicue letters of the Tibetan alphabet and receive their first formal introduction to a history, culture and religion that many Tibetans describe as embattled. [Source: Dan Levin, New York Times, January 27, 2012]

“Tibetan language is the key to our culture, and without it all our traditions will be locked away forever,” said Abo Degecairang, 25, a ruddy-cheeked monk who is among the inaugural class of young men enrolled at the school, the Anymachen Tibetan Culture Center, which opened in September 2011 here in southeastern Qinghai Province. More striking than its improbably isolated setting is the fact that the Chinese government allowed Rinpoche Tserin Lhagyal, 48, the school’s spiritual guide and soft-spoken founder, to set up an autonomous institution dedicated to promoting Tibetan culture and language. Although Tibetan areas of China are flecked with Buddhist monasteries, their mandate is to teach religious devotion through ancient texts and long hours of prayer. Nonreligious schooling is typically controlled by the state, most often anchored in Mandarin, although poverty and geographic isolation deprive many children of any formal education.

It was those young people whom the Rinpoche — a title bestowed on high-ranking teachers in Tibetan Buddhism — has sought out, eager to give them a future that he hopes will help preserve their heritage. “If your heart is in the right place, everything else will fall into place,” said the Rinpoche, who raised more than $3 million to build the vermilion-painted building topped by shimmering gold roofs. The main building, which dominates a breathtakingly picturesque valley, also houses an ornate temple filled with colorful Buddhas and altars illuminated by butter lamps. The school is so far off the grid that it must rely on solar power.

“Today, 30 shepherd boys, orphans and novice monks are learning the fundamentals of Tibetan culture, as well as Mandarin and English. Some are garbed in burgundy monks’ robes, others in jeans and trucker hats. A few arrived unable to read or write in any language, but the Rinpoche has faith that these challenges can be overcome, just as he succeeded in establishing this center despite the daunting political and financial odds. [Source: Dan Levin, New York Times, January 27, 2012]

Those who now call the center home have seen their world profoundly altered. Some, like Tuzansanzhi, 19, a shy youth dressed in monks’ robes who, like many Tibetans, uses a single name, had never been to school before. “I’m an only child, and my parents needed me to care for our sheep,” he said in Tibetan, the only language he knows. Before he arrived in July, Tuzansanzhi was illiterate. Now, he sits at a desk writing a Tibetan script that is crisply uniform.

For Tuzansanzhi and his classmates, academic instruction may be hard, but it beats their old lives. Wearing a blue track suit and brushing long black hair from his eyes, another boy, Jiuxuejop, 18, said the school had saved him from a bleak future. “I don’t want to be a herder,” he said. “I did it for over 10 years, it’s exhausting. Better to be a teacher and keep Tibetan culture alive.”

Support for the School Teaching Tibetan Ways

Dan Levin wrote in New York Times, “The Rinpoche, who has achieved the status of a “living Buddha,” says the idea for the center came to him in a vision one morning six years ago. Dismayed by the growing number of Tibetans unable to decipher the written form of their mother tongue, he dreamed of a sanctuary where young Tibetans left behind by China’s progress could study their culture and pass it on to the next generation. “Monasteries just teach monks about Buddhism, but they don’t teach the full range of how to be a Tibetan,” he said. “From a cultural point of view, it’s an emergency.” [Source: Dan Levin, New York Times, January 27, 2012]

Rather than be deterred by the tense relationship between the Communist Party and Tibetan people, the Rinpoche spent years cultivating “guanxi,” or personal relationships, with Qinghai officials. Through those efforts he methodically obtained approvals from numerous government departments. The government, he says, hopes the center, which he says will eventually house 600 students, will attract tourism and raise local living standards. To raise money, the Rinpoche traveled across China seeking donations, and received them largely from Han Chinese, who make up 80 percent of his 1,000 contributors. “Han people give me money for the same reason Tibetans donate: they want to do good,” he said. Many donors — most of them newly affluent Han — say they view Tibetan Buddhism as an antidote to the materialism and greed that have flourished alongside China’s breakneck development.

Zhu Chuanhong, 35, a banker in the southern city of Guangzhou, says she was deeply inspired after meeting the Rinpoche at a dinner party there last year. “I was so moved by his love, mercy, devotion, selflessness and determination,” she said in a telephone interview. Soon afterward she traveled to the center and handed over more than $15,000 for a well and a passenger van. Friends of hers contributed money for the center’s cafeteria and religious statuary. “That money can buy a lot more, do a lot more and mean a lot more in Qinghai than in Guangzhou,” she said.

In addition to his fund-raising quest, the Rinpoche traveled to poor villages and orphanages across Qinghai in search of those young people most in need of an education. While room and board for each student costs only $2.50 a day, teaching is more expensive. He said it cost $1,000 a month to employ an artisan from Tibet to teach the students how to paint thangkas, the intricately vibrant scrolls that depict Buddhist religious scenes. The Rinpoche hopes to enroll girls too, but given religious norms that forbid monks from mixing with women, that means building another dorm and a suite of classrooms.

Universities in Tibet

In the old days, the larger monasteries acted like universities. They contained individual colleges devoted to specific subjects and they had their own facilities and administration. Regionalism was very strong. Monk-students from the same regions were assigned to he same residence halls. Each college was headed by an abbot, or "khenpo". A geshe degree, the highest rank in the Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism, is the Tibetan Buddhist equivalent of a Ph.D. The Dalai Lama has one. "Geshe" graduates are expected to be well versed in the 320 volume of the Tibetan Buddhist canon. Usually monks have to study for 20 years before being allowed to take the exam to earn it.

The gap between the knowledge of teacher in Tibet and those outside Tibet is growing, with those outside of Tibet knowing more. In recent years geshe degrees have been awarded outside of Tibet but not in it. In June 2005, a final examination for a geshe degree was held ay Jokhang temple in Lhasa for the first time in 16 years. The Beijing-based Buddhist Association of China conducted the test in the form of a question and answer debate. Six monks in their 70s passed the test.

Conventional universities are Chinese-run. Students at the University of Lhasa face expulsion if they pray at temples or take part in religious activities. They complain they are taught not to believe in religion because religion and socialism are incompatible. Many of the students at Tibet University are Chinese studying for development jobs in Tibet.

Improving Higher Education in Tibet

In 2011, Tibet had six institutions of higher education. That year the Chinese government said it was planning to raise the higher education gross enrollment rate in Tibet to 30 percent by 2015. The enrollment rate in 2011 stood at 23.4 percent, slightly lower than the national average of 26.5 percent. According to Chinese government: “The government has earmarked $461.5 million for boosting enrollment and development in all six of Tibet's higher education institutes between 2011 and 2015. One-third of the funds was to be invested in infrastructure, while the rest will be used to improve the quality of teaching and academic research in the six institutions. [Source: China.org, July 18, 2011]

“More than 31,000 students, mostly ethnic Tibetans, currently study in Tibet's six universities and junior colleges. Of them, 718 are pursuing post-graduate degrees. In addition, many students from Tibet are studying in universities outside the region, officials said. The figures, though not impressive compared with other parts of China, are remarkable for Tibet. It did have a single university school within its borders in 1951.

Between 1951 and 2010, the central government spent billions of dollars to build educational facilities in Tibet. While the government's main focus has been placed on primary and secondary education in the past, higher education is about to receive a major boost. The government will help Tibet University, the region's top university, to grow into an internationally-recognized university, officials said. "The school is not yet a leading university in China, but is becoming one," said Professor Tubdain Kaizhub, head of the university's economics and management department. "The school's developmental momentum is so strong that we often feel great pressure."

The professor, who has been working at the university since 1985, described the changes that have taken place in Tibetan higher education over the past two decades as "tremendous." He said that when the university's economics and management department was founded in 1987, there were fewer than 100 students enrolled in the department, and only ten teachers available to instruct them. Today, the department has over 800 students. About 90 percent of the university's graduates stay in Tibet to work, the professor said. "As Tibet is in its prime time for development, I am confident that the demand for college-educated workers will keep growing," he said.

Tibetan Monks Study Science in India

Tim Sullivan of Associated Press wrote: “ In an educational complex perched on the edge of a small river valley, in a place where the Himalayan foothills descend into the Indian plains, a group of about 65 Tibetan monks and nuns are working with American scientists to tie their ancient culture to the modern world. At the forefront is an intensive summer program, stretched over five years, that brings professors from Emory University in Atlanta. For six days a week, six hours a day, the professors teach everything from basic math to advanced neuroscience. "The Buddhist religion has a deep concept of the mind that goes back thousands of years," said Larry Young, an Emory psychiatry professor and prominent neuroscientist. "Now they're learning something different about the mind: the mind-body interface, how the brain controls the body." The first group from the Emory program — 26 monks and two nuns — have just finished their five years of summer classes. While they earned no degrees, they are expected to help introduce a science curriculum into the monastic academies, and take with them Tibetan-language science textbooks the program has developed.” [Source: Tim Sullivan, Associated Press, July 3, 2012 ^/^]

The science program "was sort of like a culture shock for me," said Choegyal, who is based at a monastery in southern India. While Tibetan Buddhism puts a high value on skepticism, conclusions are reached through philosophical analysis — not through clinical research and reams of scientific data. So it was difficult, at first, for many of the students. And the questions ranged across science and philosophy: Are bacteria sentient beings? How does science know that brain chemistry affects emotions? Are Tibetan beliefs in mysticism provable through science?

After five years, Choegyal says he has managed to hold onto his core beliefs while delving deeply into science. "Buddhism basically talks about truth, or reality, and science really supports that," he said. Questions that science cannot address, like the belief in reincarnation, he brushes aside as "subtle issues." Instead, he mostly finds echoes across the two cultures. He points to karma, the ancient Buddhist belief in a cycle of cause and effect, and how it plays into reincarnation. Then he points to the similarities with evolutionary theory. "Everything evolves, or it changes," he said, whether in evolution or in reincarnation. "So it's pretty similar, except some sort of reasoning."

Tibetology

Tibetan studies, or Tibetology, is now recognized as a distinct field in international academic circles. It covers most of the basic subjects in the social and natural sciences, including political science, economics, history, literature and art, religion, philosophy, spoken and written language, geography, education, archeology, folk customs, Tibetan medicine and pharmacology, astronomy, the calendar, ecological protection, sustainable economic development, and agriculture and animal husbandry. It has brokent the narrow bounds of the "Five Major and Five Minor Treatises of Buddhist Doctrine" of traditional Tibetan culture. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China, October 26, 2005]

University students in Germany, the U.K., the U.S. and other countries can major in Tibetology. The publications of the British diplomat Charles Alfred Bell contributed towards the establishment of Tibetology as an academic discipline. Outstanding tibetologists of the 20th century included Britons Frederick William Thomas, David Snellgrove, Michael Aris, and Richard Keith Sprigg, the Italians Giuseppe Tucci and Luciano Petech, the Frenchmen Jacques Bacot and Rolf Alfred Stein, and the Germans Dieter Schuh and Klaus Sagaster. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the Chinese government, there are now more than 50 institutions of Tibetan studies and more than 1,000 experts and scholars in this field in China. In China A number of special organizations on Tibetan studies were established in Tibet since the 1970s, represented by the Tibet Academy of Social Sciences. In the past few years, the academy has made a breakthrough in Tibetan studies by completing a sequence of important monographs, including A General History of Tibet (Tibetan and Chinese editions), A Political History of Tibet by Xagaba (Annotated), A Communications History of Ancient and Modern Tibet (Chinese edition), The Inference Theory in Tibetan Philosophy (Tibetan edition), A Dictionary of Tibetan Philosophy (Tibetan edition), and Index of the Catalogues of Tibetan Studies Documents. Tibetan Studies has become one of the 100 leading Chinese periodicals on the social sciences.

Image Sources: Julie Chao, Save Tibet

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022