ELDERLY PEOPLE IN CHINA

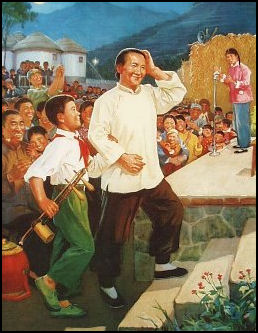

Respect for elders is often the basis for the way society is organized and has been at the foundation of Chinese culture and morality for thousands of years. Older people are respected for their wisdom and most important decisions have traditionally not been made without consulting them. Confucian filial piety encourages the younger generation to follow the teachings of elders and for elders to teach the young their duties and manners.

The elderly enjoy high status. Respect has traditionally been regarded as something earned with age. An emphasis on youth isn't as strong as it is in the West. Respect for the elderly is manifested through the custom of allowing the elderly people to go first, giving up seats to them on buses and generally deferring to them, helping them out and respecting their opinions and advise.

Respect for elders is often the basis for the way society is organized and has been at the foundation of Chinese culture and morality for thousands of years. Older people are respected for their wisdom and most important decisions have traditionally not been made without consulting them. Confucian filial piety encourages the younger generation to follow the teachings of elders and for elders to teach the young their duties and manners.

The elderly enjoy high status. Respect has traditionally been regarded as something earned with age. An emphasis on youth isn't as strong as it is in the West. Respect for the elderly is manifested through the custom of allowing the elderly people to go first, giving up seats to them on buses and generally deferring to them, helping them out and respecting their opinions and advise.

Old people are arguably among the happiest people in China. You can often find them singing and dancing in the parks or hanging out and joking around on the streets with their friends. Their cheerfulness appears to come from three sources: Confucianism, which teaches respect to one's elders; having a network of good friends; and the fact that older people, after a life of working hard, finally get a chance to kick back and relax and have their children take care of them.

Zeng Yi wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Aging”“In the cultural context of Chinese society, the philosophy regarding the support of one's older parents is quite different from that of modern Western societies. Filiality (xiao ) has been one of the cornerstones of Chinese society for thousands of years, and it is still highly valued. The philosophical ideas of filiality include not only respect for older generations but also the responsibility of children to take care of their old parents, which is stated clearly in the Chinese constitution and in laws protecting the rights of elderly persons. Families have been playing, and will continue to play, crucial roles in bearing the costs of caring for the elderly, given limited pensions and health service facilities, especially in rural areas. [Source: Zeng Yi, “Encyclopedia of Aging”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

Hsiang-ming kung wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”: “The elderly, as the closest living contacts with ancestors, traditionally received humble respect and esteem from younger family members and had first claim on the family's resources. This was the most secure and comfortable period for men and women alike. Filial piety ensured that the old father still preserved the privilege of venting his anger upon any member of the family, even though his authority in the fields might lessen as he aged. His wife, having produced a male heir, was partner to her husband rather than an outsider in maintaining the family. If not pleased, she had the authority to ask her son to divorce his wife. However, due to her gender, her power was never as complete as her husband's. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

See Separate Articles: RETIREMENT AND PENSIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; NEGLECT AND PROBLEMS SUFFERED BY ELDERLY PEOPLE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FAMILY IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com ; CONFUCIANISM, FAMILY, SOCIETY, FILIAL PIETY AND RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: People’s Daily article peopledaily.com ; China Daily article chinadaily.com ; China.org article china.org.cn ;

Population and Numbers of Elderly People in China

The proportion of those aged 65 and above of the Chinese population was 5.6 percent in 1990 and 7.0 percent in 2000. Originally it was thought this proportion would climb quickly to 15.7 percent in 2030 but ot reached 18.7 percent in 2020. In Western societies, the aging transition has been place over a longer span of time. In China, it is taking place in a few decades. In 1990 there were 67 million people 65 and over. In 2000, there 87 million. Again projections in 2000 predicted 235 million elderly in China in 2030, but again that figure was more or less reached in 2020. [Source: Zeng Yi, “Encyclopedia of Aging”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

Chinese over 60, who numbered 264 million, accounted for 18.7 percent of China’s total population in 2020, 5.44 percentage points higher than in 2010, according to the 2020 Chinese census. At the same time, the working-age population fell to 63.3 percent of the total from 70.1 percent a decade ago and Meanwhile, the number of working-age people in China has fallen over the past decade and the population has barely grown. The elderly population is unevenly distributed. Most live in the less well-off rural areas. [Source: Associated Press, August 21, 2021]

Fertility in China has declined dramatically from more than six children per woman in the 1950s and 1960s to 1.3 children per woman today, which is one of the lowest rates in the world. Average life expectancy at birth for both sexes combined in China has increased from about 41 years in 1950 to 68.4 years in 1990, and 71 years in 2000 to 77 in 2019. The large numbers of baby boomers born in the 1950s and 1960s are becoming elderly now. [Source: Zeng Yi, Encyclopedia of Aging, Gale Group Inc., 2002, with modern data]

Population 65 and above: 12 percent (compared to 3 percent in Kenya, 17 percent in the United States and 28 percent in Japan). [Source: World Bank data.worldbank.org ]

China’s Elderly Live Longer, But Are Less Healthy, Fit, Study Says

The number and proportion of people in China over 80 are growing, but their mental and physical fitness appear to be declining. AFP reported: “Comparing medical data and surveys from 1998 and 2008 of nearly 20,000 people aged 80 to 105, researchers found that the ranks of China’s ‘oldest old’ had expanded since the turn of the century. For octogenarians and nonagenarians, mortality fell by nearly one percent over that decade, they reported in the medical journal The Lancet. For the 100-and-up club, death rates dropped nearly three percent.

The ‘over 80’ cohort is by far the fastest rising age group in the country. [Source: Agence France-Presse, March 10, 2017]

The number and proportion of people in China over 80 are growing, but their mental and physical fitness appear to be declining. AFP reported: “Comparing medical data and surveys from 1998 and 2008 of nearly 20,000 people aged 80 to 105, researchers found that the ranks of China’s ‘oldest old’ had expanded since the turn of the century. For octogenarians and nonagenarians, mortality fell by nearly one percent over that decade, they reported in the medical journal The Lancet. For the 100-and-up club, death rates dropped nearly three percent.

The ‘over 80’ cohort is by far the fastest rising age group in the country. [Source: Agence France-Presse, March 10, 2017]

“At the same time, however, physical and cognitive function showed a small but significant deterioration. Simple tasks — standing up from a chair, for example, or picking up a book off the floor — were harder to perform, while scores on memory tests slumped. “This has clear policy implications for health systems and social care, not only in China but also globally, ” the authors concluded. “Many more state-subsidized public and private programs and enterprises are urgently needed to provide services to meet the needs of the rapidly growing elderly population, ” especially those over 80.

“Paradoxically, the 2008 respondents reported less difficulty in performing daily activities — such as eating, dressing and bathing — than those born a decade earlier. The scientists, led by Yi Zeng, a professor at the National School of Development at Beijing University, chalked this up to improved amenities and tools, but said more research was needed. The findings illustrate the tug-of-war between two approaches to assessing ageing populations, whether in rich or developing countries. One emphasizes the “benefits of success”: people living longer with lower levels of disability because of healthier lifestyles, better healthcare and higher incomes. By contrast, the “cost of success” theory suggests that living longer might mean that individuals survive life-threatening illnesses but live with chronic health problems as a result.

“The new study shows that both theories are at play, and that governments will need to adapt under either scenario. “The findings provide a clear warning message to societies with ageing populations, ” Yi said in a statement. “Although lifespans are increasing, other elements of health are both improving and deteriorating, leading to a variety of health and social needs in the oldest-old population.” Whether it means providing long-term care for the disabled, or work and social opportunities for healthy octogenarians, adjusting to an ageing population will require planning and investment, the researchers concluded.

Graying of China

A major consequence of a low birth rate and the one-child policy has been an increasingly older population. China’s elderly population is growing rapidly while the number of young adults is shrinking, a huge demographic shift that has been building for decades. While the elderly still make up a relatively small share of China’s population compared with some Western nations, their proportion of the population nearly doubled in the 2000s and 2010s. By 2050, some demographers predict, one in four Chinese will be 65 or older. The 2020 census showed that people over 60 years of age account for almost 18 percent of the populace, compared 13.26 percent in 2010 and 10.33 percent in 2000. By 2040, this figure is projected to spike to a stunning 28 percent. A 2010 study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) forecast that by 2030, the proportion of the population that is over 65 will exceed even that of Japan, which has the grayest population in Asia. "By 2050, Chinese society will enter into a phase of severe agedness," the CASS said. [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, Jamestown Foundation, May 6, 2011]

China is quickly fulfilling the oft-repeated adage that "China is becoming old before it becomes rich." China’s demographic dividend — a reference to speedy economic expansion due to an increase of the proportion of Chinese who are working — is forecast by official economists to decline sharply from around 2013. And by 2039, less than two Chinese taxpayers may have to look after one retiree.

The nation’s elderly population could reach 400 million by the end of 2035, up from 240 million in 2018, year, according to government forecasts. As of 2005 about 143 million people (more than 10 percent of the population) were over 60. This is more than population of all but about ten countries. The rate is expected to increase at a rate of 100 million a decade. By 2050, there are expected to be 438 million elderly, or one out of four Chinese, compared with one out of ten in 1980. By 2020 the number of people between 20 and 24 is expected to be half of the 124 million in 2010. During the same time period the number of people over 60 is expected to jump from 12 percent of the population — 167 million people — to 17 percent. By 2050 China will have more than 100 million over 80.

See Separate Articles POPULATION OF CHINA: STATISTICS, REGIONS AND RESULTS OF THE 2020 CENSUS factsanddetails.com POPULATION GROWTH IN CHINA: HISTORY, DECLINES, REASONS AND IMPACTS factsanddetails.com DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES IN CHINA: AGING POPULATION, BIG PENSION PAY OUTS, LABOR SHORTAGES AND SLOWED ECONOMIC GROWTH factsanddetails.com

Rural Versus Urban Elderly in China

The elderly in the countryside is really worrying,” said Therese Hesketh, a professor of global health at the University College London who has studied China’s population policies. “Even in the U.K. at Christmastime, this is an issue that comes up,” with smaller families and couples deciding whose parents to visit, Hesketh said. “This is a universal issue magnified in China by the one-child policy.”

Zeng Yi wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Aging”: “Although fertility in rural China is much higher than in urban areas, aging problems will be more serious in rural areas because of the continuing massive rural-to-urban migration, the large majority of which is young people. Under the medium fertility and medium mortality assumptions, the proportion of elderly will be higher in rural areas than percent in urban areas.[Source: Zeng Yi, “Encyclopedia of Aging”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

According to a national survey on China's support systems for the elderly, conducted by the China Research Center on Aging in 1992, 12.7, 53.1, 22.7, and 11.6 percent of the rural elderly reported that their monthly income was enough with savings, roughly enough, a little bit difficult, and rather difficult, respectively. The corresponding figures for the urban elderly were 15.3, 63.9, 15.9, and 5.0 percent, respectively. About 0.8, 47.4, 14.7, and 7.3 percent of the rural elderly had a telephone, a television set, a washing machine, and a refrigerator in their home, in contrast to 7.5, 88.2, 51.5, and 46.6 percent for the urban elderly (CRCA, 1994). Obviously, the economic status of the rural elderly is substantially worse than that of their urban counterparts.

Although this data is very old, similar patterns probably exist today. “Based on the 1992 survey, 66.6 percent of the urban elderly had their medical expenses paid entirely or partially by the government or collective enterprises in 1991. However, this figure was only 9.5 percent for the rural elderly (CRCA, 1994). According to a national survey on healthy longevity of the oldest old conducted by China Research Center on Aging and by Peking University in 1998, around 80 percent of the Chinese oldest old reported that they could get adequate medical care when they were sick. Note that the term "medical care" used in the survey includes traditional Chinese medicine, which is cheap and widely available even in poor and remote areas. As a result, we should not interpret the 1998 survey figures as an indication of good and modern health service facilities in China today. [Source: Zeng Yi, “Encyclopedia of Aging”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

Respect for Older People and Taking Care of Them in China

Many codes of behavior revolve around young people showing respect to older people. Younger people are expected to defer to older people, let them speak first, sit down after them and not contradict them. Sometime when an older person enters a room, everyone stands. People are often introduced from oldest to youngest. Sometimes people go out their way to open doors for older people and not cross their legs in front of them. When offering a book or paper to someone older than you, you should show respect by using two hands to present the object. On a crowded subway or bus, you should give up your seat to an elderly person.

Sometimes a comment based on age meant to be complimentary can turn out to be an insult. The New York Times described a businessmen who was meeting with some high-ranking government officials and told one them he was “probably too young to remember.” The comment was intended to be a compliment — that the official looked young for his age — but it was taken as insult — that the officials was not old enough to be treated with respect.

Respect for elders is best expressed during the "elder’s first" rite, the central ritual of the Chinese New Year, in which family members kneel and bow on the ground to everyone older than them: first grandparents, then parents, siblings and relatives, even elderly neighbors. In the old days a son was expected to honor his deceased father by occupying a hut by his grave and abstaining from meat, wine and sex for 25 months.

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”:“It is the Chinese theory that parents are to be taken care of in old age by their children either in combination or in rotation. But cases in which aged mothers have a portion to themselves, doing all their own cooking and most of the other necessary work are everywhere numerous. A Westerner is constantly struck with the undoubted fact that the mere act of dividing a property seems to extinguish all sense of responsibility whatever for the nearest of kin. It is often replied when we ask why a Chinese does not help his son or his brother who has a large family and nothing in the house to eat, “We have divided some time ago.” The real explanation is perhaps to be found in the accumulated exasperations of the larger part of a lifetime, once delivered from which, a Chinese feels that he can judiciously expend his energies in looking out for Number2 One, leaving the rest of the series to do the same as best they may. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company,1899, The Project Gutenberg]

Filial Piety in Modern China

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “They are exemplars from folklore who are familiar to Chinese school children. There is the Confucian disciple who subsisted on wild grass while traveling with sacks of rice to give to his parents. There is the man who worshiped wooden effigies of his parents...Guangzhou Daily, an official newspaper, ran an article in October about a 26-year-old man who pushed his disabled mother for 93 days in a wheelchair to a popular tropical tourist destination in Yunnan Province. The article called it “by far the best example of filial piety” in years. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, July 2, 2013]

“The classic text that has been used for six centuries to teach the importance of respecting and pampering one’s parents has been “The 24 Paragons of Filial Piety,” a collection of folk tales written by Guo Jujing. In August 2012, the Chinese government issued a new version , supposedly updated for modern times, so today’s youth would find it relevant. The new text told children to buy health insurance for their parents and to teach them how to use the Internet.

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times, The Chinese government has launched a multipronged effort to remind people to take an active role in their parents' lives. The new version of "The 24 Paragons of Filial Piety," features a woman who feeds her toothless mother-in-law breast milk to keep her alive; a son who tastes his father's excrement to help a doctor diagnose his ailment — the federation had some suggestions more in line with the 21st century. Photograph your parents regularly, throw birthday parties for them, teach them how to use the Internet, make an emergency contact card they can carry with them. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, July 29, 2013]

“Meanwhile, the state-run broadcaster CCTV has aired a series of tear-jerking commercials focusing on parent-child relationships. In one, an elderly man tells his daughter over the phone that he's busy with friends, that her mother is out dancing, and that it's OK if she doesn't come visit. In reality, he's sad and lonely, and his wife is in a hospital. "Can you hear your father's lies?" a voice-over asks.”

See Separate Article CONFUCIANISM, FAMILY, SOCIETY, FILIAL PIETY AND RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com

Living Arrangements and Family Support of Elderly Chinese

Zeng Yi wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Aging” in the early 2000s: “Among the elderly, 37.4 percent of men and 66.5 percent of women do not have a surviving spouse. The proportion of those not living with a spouse increases tremendously with age, due to high rates of widowhood at advanced ages (the divorce rate in China is very low). Many more elderly women are widowed than men because of the gender differential in mortality at old ages. The proportion of old men and women living alone is 8.0 and 10.2 percent, respectively. Elderly women are more likely to be widowed and thus live alone. On the other hand, elderly women are economically more dependent. Therefore, the disadvantages of women in marital life and living arrangements are substantially more serious than those of men at old ages (Zeng and George, 2000).[Source: Zeng Yi, “Encyclopedia of Aging”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

“On the basis of 1990 census data, a large majority of old men (68.8 percent) and women (74.8 percent) live with their children ("children" includes grandchildren hereafter). Female elderly persons are more likely to live with their children, because elderly women are more likely to be economically dependent and widowed. Among the elderly who live with offspring, a majority (68.5 percent of men and 80.1 percent of women) live with both children and grandchildren. Multigeneration family households are one of the main living arrangements for the elderly.

Hsiang-ming kung wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”:“The life of widows in traditional China was no less miserable than that of divorced women. Although widowers could remarry without restraint, the pressure of public opinion ever since Sung dynasty (A.D. 960-1279) prevented widows from remarrying. The remarriage of widows was discouraged, and their husbands' families could actually block a remarriage. Nor could the widow take property with her into a remarriage. The only way a widow could retain a position of honor was to stay as the elderly mother in her late husband's home. This way, her family could procure an honorific arch after her death (Yao 1983). A widow's well-being was less valuable than the family's fame. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Elderly People and Their Children in China

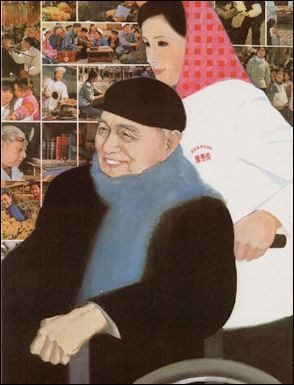

Old people have traditionally been taken care of by their children. Nursing homes for the elderly are still an alien idea in much of Asia. Those that enter nursing homes often feel as if they are being sent away and rejected. The families that put them there feel guilty. Three in ten Chinese families have grandparents living in the same household. Things are changing quick. Just a few years ago, about 70 percent of China's elderly people, particularly in rural areas, live with their children or relatives while less than 1 million live in retirement homes.

The demographics expert Cai Feng told Newsweek the one-child generation are “more likely to be spoiled and self-centered. As adults, children of this generation lack the inclination to support their parents.” A law passed in 1996, stipulated that children were responsible for taking care of their parents in old age. Still a lot of young Chinese have said they are willing to take care of their elderly parents. In one survey, 66.2 percent of Chinese high school students said they planned to take care of their parents in old age (compared to of 15.7 percent of Japanese high school students).

“Once ensconced in intimate neighborhoods of courtyard houses and small lanes and surrounded by relatives and acquaintances, older people in China are increasingly moving into lonely high-rises and feeling forgotten,” Lafraniere wrote. “Whereas once several generations shared the same dwelling, more than half of all Chinese over the age of 60 now live separately from their adult children, according to a November 2010 report by China’s National Committee on Aging, an advisory group to the State Council. That percentage shoots up to 70 percent in some major cities, the report said. Half of those over the age of 60 suffer from chronic illness and about 3 in 10 suffer from depression or other mental disorders, the group said.

In 2006, 42 percent of Chinese families consisted of an old couple living alone. In a survey in 2002, half of the elderly respondents said they preferred to live alone rather than with their children. The finding dispelled the concept that most elderly Chinese want to be taken care of by their children.

In China there are contests for best children, The winner of the Model Filial Daughter-in-Law contest in Shanxi in 2006 received $60 prize and the opportunity to compete in the national contest. She cheerfully took care of her father-in-law and disabled sibling for two decades. The winner of the National Person of the Year contest gave his mother one of his kidneys without saying anything. “My contribution to may mother does not compare to what she has given me,” he said. Dramas on state-run television that deal with filial themes include "Nine Daughters at Home" and "My Old Parents".

There are newspapers ads that link lonely elderly people who feel ignored by their children with adult women who want to be adopted. The women, who tend to be married and and in their 40s, visit their elderly hosts on the weekends and do things like clean and play cards with their host. One host told Newsweek, “I consider them my real daughters now.”

Elderly Care Burdens Families

Lihong Shi of Case Western Reserve University wrote in The Conversation: “In China, where the pension and health care systems are patchy and highly stratified, adult children are the main safety net for many aging parents. Their financial support is often necessary after retirement. Due to the country’s longstanding tradition of filial piety, children also have a moral obligation to support their aging parents. Parental care is actually the legal responsibility of children in China; it is written into the Chinese Constitution.” [Source: Lihong Shi, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Case Western Reserve University, The Conversation, September 26, 2021]

China's relative lack of wealth and a shortage of qualified health caregivers has hindered the elderly health care sector, keeping the burden of care on families. Gabriel Crossley of Reuters wrote:“Nie Guihua, 72, has been looking after her husband, Yang Shulin, for nearly two decades, He had a stroke at 55, can no longer speak, and uses a wheelchair. Nie also helps care for her two grandchildren. Nie and her husband each get 800 yuan [US$125] a month from the state — about two-thirds the cost of a care home near where they live in a village outside Beijing.[Source: Gabriel Crossley, Reuters, July 9, 2021]

“Her son, Yang Xiaoli, who is divorced, drives buses for a living, and often only gets home late at night. Nie, a former farmer, was fined for having her son under the one-child policy, a key contributor to China's rapidly aging population that was relaxed in 2016. Yang said even if they could afford such care, other pressures would make it impossible. "If my mum and my dad were in a care home, who would look after the kids?" he said. Bei Wu, a professor at New York University who has researched aging in China since the 1980s, said high fees and poor staffing push away potential residents. [Source: Gabriel Crossley, Reuters, July 9, 2021]

China’s One-Child Policy Left 1 Million Elderly With No One to Take Care of Them

Lihong Shi of Case Western Reserve University wrote in The Conversation: “A child’s death is devastating to all parents. But for Chinese parents, losing an only child can add financial ruin to emotional devastation. That’s one conclusion of a research project on parental grief I’ve conducted in China since 2016. From 1980 to 2015, the Chinese government limited couples to one child only. I have interviewed over 100 Chinese parents who started their families during this period and have since lost their only child — whether to illness, accident, suicide or murder. Having passed reproductive age at the time of their child’s death, these couples were unable to have another child. [Source: Lihong Shi, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Case Western Reserve University, The Conversation, September 26, 2021]

“The childless parents I interviewed told me they felt forgotten as their government moves further away from the birth-planning policy that left them bereaved, alone and precarious in their old age — in a country where children are the main safety net for the elderly. “We wanted to have more children,” said a bereaved mother who was in her 60s when I interviewed her in 2017. “My parents had an even harder time accepting that we were allowed to have only one child.” Several bereaved mothers told me that they had gotten pregnant with a second or third child in the 1980s or 1990s but had an abortion for fear of job loss.

It is estimated that 1 million Chinese families had lost their only child by 2010. These childless, bereaved parents, now in their 50s and 60s, face an uncertain future.“Families with an only child are walking on a tightrope. Every family can fall off the tightrope at any moment” if they lose their only child, one bereaved mother explained to me. “We are the unlucky ones,” she said.

A safety net does not exist for parents who lost the only child the government would let them have. Over the past decade, groups of bereaved parents have negotiated with the Chinese authorities to demand financial support and access to affordable elder care facilities. Those I interviewed said they had fulfilled their obligation as citizens by abiding by the one-child rule and felt the government now had the responsibility to take care of them in their old age.

Eventually, the authorities responded to their grievances. Starting in 2013, the government has initiated multiple programs for bereaved parents, most notably a monthly allowance, hospital care insurance and in some regions subsidized nursing home care. However, bereaved parents told me that these programs were insufficient to meet their elder care needs.

For example, adult children often take care of their parents during hospitalization, bathing them and buying meals. Private care aides can charge up to US a day, or 300 yuan, to do these tasks. In regions that now provide government-paid hospital care insurance for childless parents, most plans cover between .50 to — about 100 to 200 yuan — daily for a care aide, based on my research. Other people I interviewed worried about the high cost and limited availability of quality nursing homes in many regions. China’s elder care facilities cannot meet the demand of its aging population, and living in these facilities is not covered by insurance.

Lack of Nursing Homes and Elderly Caregivers in China

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “Rapid urbanization, coupled with the one-child policy and other societal changes, has left tens of millions of elderly people living alone, often with little in the way of government aid. China has few nursing homes and no tradition of professional caretakers to look after the elderly when they become infirm. [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, January 18, 2012]

The number of elderly living in nursing homes in China relative to Western countries is very low. The census data from 1990 revealed that that the proportions of elderly men and women who lived in nursing homes in 1990 in the urban areas were 2.1 and 0.8 percent, respectively. The corresponding figures for rural elderly men and women were 0.8 and 0.2 percent, respectively. [Source: Zeng Yi, “Encyclopedia of Aging”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

Things haven't changed all that much since then. In 2008, it was estimated 1.5 percent of older people lived in nursing homes and apartments for older people. Because of the peculiar 4-2-1 family structure in China, it is expected the demand for nursing home placement of older adults will increase in the coming years. [Source: "Nursing Homes in China by Winnie C W Chu, The Chinese University of Hong Kong and Iris Chi, University of Southern California, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, June 2008]

Gabriel Crossley of Reuters wrote: “China planned a decade ago to train 6 million caregivers by 2020. Just 300,000 were qualified by 2017, according to a report cited by state news agency Xinhua. The latest calls for 2 million to be trained by 2022. Until recently almost all the elderly were looked after by family members, Wu said. But shrinking families, migration, and a decline in a sense of filial duty has led to the "erosion of the family support system, " she said. [Source: Gabriel Crossley, Reuters, July 9, 2021]

“Without more frontline staff and expanded community-based care, the pressures on families will mount, she said. Yang Wei, an engineer from northern Hebei province, said that his grandfather, who is nearly 90, had wanted to try out a care home to reduce the stress on his family after a bad fall. He moved into one that cost 4,000 yuan a month. But staff didn't seem to care about residents' well being, Yang said. "The staff weren't professional. And there weren't enough, " Yang said. "Even if you spend more money... it is still difficult for the elderly to enjoy good care in nursing homes, and families can't be completely at ease. So we took Grandpa home."

Nice Facilities for the Elderly Chinese That Can Afford and Get Into Them

In 2021, Gabriel Crossley of Reuters wrote:“ In Heyuejia, a care home in western Beijing, new residents announced their advanced ages and illustrious former careers to applause from a crowded hall, before tucking into a candle-decorated cake and dancing. Spacious rooms, nutritious food, and activities from calligraphy to art therapy are on offer to residents — largely retired professionals — for around 10,000 yuan ($1, 542) a month. Prices scale with the level of care needed. [Source: Gabriel Crossley, Reuters, July 9, 2021]

“Wang Yiguang, 85, a retired scientist who moved into Heyuejia in 2018, likes the care home and can comfortably afford it. "Here you have someone to help you at any time, and there's a doctor to see if you need to go to the hospital, " Wang said. One of her sons, living in the U.S., had resisted the move. He had seen Americans in care homes who seemed sluggish and irritable. But her son came around when he saw how happy his parents were, said Wang, who sings in a Russian-language choir with other residents who studied in the Soviet Union.

“HNA Investment Group opened Heyuejia in 2016 as part of efforts to "respond to China's aging crisis, " according to a company statement. Helped by government subsidies, more than 40,000 registered homes have been built in recent decades. But many are too expensive or too low quality to replace family care, experts say. Some facilities have long waiting lists. But most are quite empty — average occupancy rates are as low as 50 percent, official data suggests, far lower than the 80 percent-90 percent rates seen in Japan or the UK.

In 2012, Leo Lewis wrote in The Times: “It is mid-morning on the outskirts of Tianjin and the sales agents at the Eco Health Farm are zealously touting the joys of the mahjong greenhouse, the pumpkin farm and the ultimate luxury of a 24-hour "happiness butler". Beyond the manicured showroom, welding guns and cranes work in a grinding din of effort, battling to finish the compound and be ready for an experiment designed to spare China from demographic calamity. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, July 28, 2012]

Anyone can buy "dwelling rights" to Eco Health Farm apartments for between £50,000 and £90,000, but the only inhabitants will be women over 50 and men over 55. The dwelling rights become a fully tradeable asset, and the developer will buy the rights back unless they can be sold to someone else at a profit.The concept, though not entirely new to the West, is designed to address a series of complex social changes in China between the generations - problems that have been warped and amplified by 30 years of China's one-child policy.

The Eco Health Farm is designed to play on precisely that set of tensions: the young can throw their money at the problem with relatively low risk and guilt, while their parents are cared for, for an annual fee, under the guise of continuing rural life. If the Eco Health Farm works, say academics, copycat versions may emerge, and the area between Beijing and Tianjin could emerge as one of several Florida-style clusters housing millions of pensioners. The Eco Health Farm, built by a state-owned company and taking its instructions directly from a paragraph in the 12th Five-Year Plan of the Chinese Communist Party, represents growing political panic in Beijing over China's impending ageing crisis. Pitching luxury retirement villages to the elderly may seem an odd way to defuse the time bomb, but, say demographers, there are not many other bright ideas out there.

Image Sources: 1) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 2) Photos, Beifan and Julie Chao

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021