NAMES FOR CHINA

calligraphy by the famous Tang Poet Li Bai

China was named by Europeans after the ancient Ch'in Dynasty of the 3rd century B.C. This dynasty in turn was named after Emperor Qin (Chin) Shihuang, the man credited with unifying China. China is known today as the People's Republic of China “(Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo in Romanized Chinese, or Zhong Guo for short).

Chung-kho, the Chinese name for China, means "Middle Kingdom." It is derived from the traditional Chinese belief that China lay in the middle of a flat earth, with deserts and oceans around the edges. The Chinese people call themselves Hans in honor of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220), which itself was adopted from the name of a river. According to “Countries and Their Cultures”: The Middle Kingdom name is also an indication of how central the Chinese have felt themselves to be throughout history. There are cultural and linguistic variations in different regions, but for such a large country the culture is relatively uniform. [Source: Eleanor Stanford,“Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

China was first known to ancient Europeans as Serica and the people of Serica were called the Seres, a word of ancient Greek origin. Serica was one of the easternmost places in Asia known to ancient Greek and Roman geographers. It is generally thought to refer to North China during the Zhou, Qin, and Han dynasties (11th century B.C. to A.D. 2nd century) and was reached by the overland Silk Road. Serica is the source of the word sericulture ( the rasiing of silkworms to produce silk.). Sinae was another ancient name for China — particularly southern China reached via the maritime routes. It is the source of the word Sinology (the study of Chinese culture). [Source: Wikipedia]

A similar distinction between north and south China was made during medieval time with "Cathay" (north) and "Mangi" or "China" (south). The word Cathay comes form the Karakitay dynasty, an 11th century Buddhist empire in western China. In the Silk Road era this was the first part of China that Europeans reached when the approached China from the west.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: FIRSTS, ACHIEVEMENTS AND THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com; THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY: CIVILIZATION, FOREIGNERS AND THE DEFINITION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE HISTORY, POLITICS, AND VIEWS OF THE STATE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE DYNASTIES AND RULERS factsanddetails.com; FAMILY AND GENDER IN TRADITIONAL CHINA factsanddetails.com; SIMA QIAN AND THE HISTORY OF CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"China: A History (Volume 1): From Neolithic Cultures through the Great Qing Empire, (10,000 BCE - 1799 CE)" Amazon.com:

"The Cambridge Illustrated History of China"

by Patricia Buckley Ebre Amazon.com:

"China: A History"

by John Keay Amazon.com:

"Lonely Planet China" 16 Amazon.com

Chee-Na: A Derogatory and Offensive Name for China

Through much of its history ‘Chee-na’ was a neutral expression, but its association with Japanese aggression turned it into a taboo word. There have been times when Hong Kong activitists have used it show their distaste for the Central Chinese government. Sixtus “Baggio” Leung Chung-hang and Yau Wai-ching stirred up outrage when they said “Chee-na” during their swearing-in ceremony as the city’s newly elected legislators,

Chow Chung-yan wrote in South China Morning Post: ““The Chinese word [Chee-na] first appeared in the Buddhist scriptures of the Tang dynasty (6th century). It is believed to be the phonetic translation of the ancient Sanskrit word “cina”. Some see this as the origin of the English word “China”, but there is no conclusive evidence to support that. “For most of its history, the term has had no derogatory meaning. Some scholars even argue that it is actually not the name of any particular country, but a loose expression for “land of the east”. [Source: Chow Chung-yan, South China Morning Post, October 30, 2016]

“The Chinese themselves almost never use it. In fact, even Zhongguo — the Middle Kingdom — was not often used in ancient times. Before the 1911 revolution, China existed not as a nation state in the Westphalian sense. It was a civilisation with an unbroken line of imperial dynasties. People referred to themselves as “people of the great Qing” or “people of the great Tang”. Few would call themselves “people of Zhongguo”, even fewer would use “Chinese”.

“The word “Chee-na” was introduced to Japan — whose writing system borrowed heavily from Chinese — in the Tang dynasty. But it was used only as a geographic term rather than the name of any particular country or people. For centuries, Japan followed its neighbour’s tradition and addressed China by its dynasty name. This changed after the outbreak of the Opium War in 1839 between China and Britain. The humiliating defeat of the Qing empire and the loss of Hong Kong shattered China’s millennia-old worldview and its sense of cultural superiority. The Chinese civilisation entered a century of sharp and painful decline. Japan, on the other hand, quickly reinvented itself after the Meiji Restoration. It was the most successful, in fact the only, Asian country that transformed peacefully from an ancient regime into a modern nation state. Japan gradually lost its respect for the giant across the sea and started to look at China with contempt and a predatory interest.

“The first Sino-Japanese war in 1894 ended in total disaster for the Qing court. The Chinese elite were shocked to their core. Within two decades, the Qing dynasty was overthrown and China was declared a modern republic. Initially, China and Japan enjoyed a decade-long “golden relationship” shortly after the war. Many Japanese intellectuals were genuinely sympathetic towards China and hoped to get their Asian brethren back up on their feet. Many Chinese revolutionary leaders — from Sun Yat-sen to Chiang Kai-shek and Zhou Enlai — lived or studied in Japan. The modern Chinese language, in turn, borrowed extensively from Japanese. “Chee-na”, together with many other words like “economy”, “democracy” and “police”, was reintroduced back to China.

“At that time, the word had no obvious derogatory implication. In the run-up to the collapse of the Qing empire, people increasingly stopped seeing the Manchurian court as the legitimate representation of the Chinese civilisation. Japanese scholars ceased to refer to China as “the great Qing”. More and more of them started to use the word “Chee-na” as a neutral geographical expression. Sun and some early Chinese national revolution leaders did use the word in their writing at that time as they refused to see themselves as the subject of the Qing and the modern Chinese state had yet to come into being.

“But then the meaning of the word started to undergo a dramatic transformation. It was increasingly used in Japan as a demeaning way to address China and its people, implying that they were a sub-class. Japanese scholar Sato Nobuhiro, founder of the “Greater Asia” concept, used the term in his influential book, A Secret Strategy for Expansion, to suggest that China existed not as a political entity but a mere geographic expression. His work became the intellectual inspiration of Japanese imperialism towards China.

““Chee-na” quickly became a taboo word in China. While in Japan, it was used more and more as an insult. The Chinese government banned the use of the word shortly after the establishment of the republic. In 1930, the Nanjing government formally requested Japan to stop using it to address China. The Tokyo civilian government complied but the imperialist advocates continued to use the word. It implied that China was not worthy to be recognised as a sovereign state and it existed only as a geographical expression. This was used to justify Japan’s aggression.The psychological association of “Chee-na” with Japanese aggression and invasion became inseparable following the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was widely used in the propaganda materials of the Japanese military. Today, using the word will inevitably bring back that painful history to Chinese people everywhere, particularly those who had witnessed and endured all the horrors of the war.

Creation of China

Emperor Qin

Over several millennia, China absorbed the people of surrounding areas into its own civilization while adopting the more useful institutions and innovations of the conquered people. Peoples on China's peripheries were attracted by such achievements as its early and well-developed ideographic written language, technological developments, and social and political institutions. The refinement of the Chinese people's artistic talent and their intellectual creativity, plus the sheer weight of their numbers, has long made China's civilization predominant in East Asia. The process of assimilation continued over the centuries through conquest and colonization until the core territory of China was brought under unified rule. The Chinese polity was first consolidated and proclaimed an empire during the Qin Dynasty (221--206 B.C.). Although short-lived, the Qin Dynasty set in place lasting unifying structures, such as standardized legal codes, bureaucratic procedures, forms of writing, coinage, and a pattern of thought and scholarship. These were modified and improved upon by the successor Han Dynasty (206 B.C.--A.D. 220). Under the Han, a combination of the stricter Legalism and the more benevolent, human-centered Confucianism — known as Han Confucianism or State Confucianism — became the ruling norm in Chinese culture for the next 2,000 years. Thus, the Chinese marked the cultures of people beyond their borders, especially those of Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Much of what came to constitute China Proper was unified for the first time in 221 B.C. In that year the western frontier state of Qin, the most aggressive of the Warring States, subjugated the last of its rival states. (Qin in Wade-Giles romanization is Ch'in, from which the English China probably derived.) *

Once the king of Qin consolidated his power, he took the title Shi Huangdi (First Emperor), a formulation previously reserved for deities and the mythological sage-emperors, and imposed Qin's centralized, nonhereditary bureaucratic system on his new empire. In subjugating the six other major states of Eastern Zhou, the Qin kings had relied heavily on Legalist scholaradvisers . Centralization, achieved by ruthless methods, was focused on standardizing legal codes and bureaucratic procedures, the forms of writing and coinage, and the pattern of thought and scholarship. To silence criticism of imperial rule, the kings banished or put to death many dissenting Confucian scholars and confiscated and burned their books. Qin aggrandizement was aided by frequent military expeditions pushing forward the frontiers in the north and south. *

To fend off barbarian intrusion, the fortification walls built by the various warring states were connected to make a 5,000- kilometer-long great wall. (What is commonly referred to as the Great Wall is actually four great walls rebuilt or extended during the Western Han, Sui, Jin, and Ming periods, rather than a single, continuous wall. At its extremities, the Great Wall reaches from northeastern Heilongjiang Province to northwestern Gansu. A number of public works projects were also undertaken to consolidate and strengthen imperial rule. These activities required enormous levies of manpower and resources, not to mention repressive measures. Revolts broke out as soon as the first Qin emperor died in 210 B.C. His dynasty was extinguished less than twenty years after its triumph. The imperial system initiated during the Qin dynasty, however, set a pattern that was developed over the next two millennia. *

Languages in China

Early writing from Neolithic Shandong

The Chinese define a nationality (ethnic group) as a group of people of common origin living in a common area, using a common language, and having a sense of group identity in economic and social organization and behavior. Altogether, China has fifteen major linguistic regions generally coinciding with the geographic distribution of the major minority nationalities. Members of non-Han groups, referred to as the "minority nationalities," constitute only about 7 percent of the total population but are distributed over 60 percent of the land. [Source: Library of Congress]

Most nationalities have their own language. Some have their own script, although some of these have fallen into disuse under Communist rule. Over the centuries a great many peoples who were originally not Chinese have been assimilated into Chinese society. Entry into Han society has not demanded religious conversion or formal initiation. It has depended on command of the Chinese written language and evidence of adherence to Chinese values and customs.

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “One of the most unusual aspects of Chinese culture is the Chinese language. It includes a vast array of regional dialects, many of which cannot be understood by Chinese of other regions, and it features the use of inflectional tones to distinguish among different words, otherwise pronounced identically. These characteristics make Chinese dramatically different from European languages, and it is relatively difficult for speakers of English and Romance languages to learn. But these differences also make Chinese a language of unusual interest. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

“Because Chinese characters do not give a clear indication of their pronunciation, regional differences in pronunciation of Chinese were likely always very broad, and particularly after the migrations that led to the development of equally strong Northern and Southern regions, the local dialects of Chinese diverged to the same degree that dialects of Latin in Europe diverged to create the various Romance languages. Today, the language spoken in the southern port cities of Guangzhou and Hong Kong, “Cantonese,” is at least as far removed from the language spoken in Beijing as Spanish is from French. However, the disjunction between writing and pronunciation has had the contrary effect of preserving the universal intelligibility of written Chinese, which has consequently served to reinforce the cultural and political unity of China. Thus Chinese may be considered the language of the “Han” Chinese people, who comprise the overwhelming majority of the population. /+/

“China includes many ethnic groups that were brought within Chinese boundaries through processes of imperial expansion: Uighurs, Tibetans, Mongols, and a host of others. The most influential of these groups speak and write their own languages with non-Chinese scripts, and in some cases prefer not to use Chinese, which to them is the language of an occupying power. However, from the early twentieth century, there has been an increasingly active effort by Chinese governments to ensure that a version of Chinese known as Mandarin – closely related to the dialect of Beijing – be universally taught in schools and used for all official transactions. The active spread of Mandarin, particularly once the use of radios and televisions became widespread, has created a common spoken language that can be understood by people in almost all regions. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

See Separate Articles: HISTORY OF WRITING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com

Ancient Chinese Language

Dr. Eno wrote: “The earliest evidence of writing that reflects the spoken Chinese language dates back over three thousand years to the lower Yellow River Valley. Ancient Chinese seems to have been part of the same linguistic lineage that produced the languages of Tibet and Burma, and it is generally considered part of the “Sino-Tibetan” language group. The earliest Chinese states were formed from a coalescence of many different peoples, speaking many different languages, but because among them only Chinese could be written, it came in time to be the universal language of the Chinese state. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

China's language groups in 1983

“Even those who love ancient Chinese admit that the language is bizarre and that it creates unusual difficulties for the study of China in Western languages...We have little insight into the spoken language of ancient China. The texts we possess now are, being texts, all examples of the written language, and there is much evidence to support the view that spoken and written languages were very different in antiquity. In fact, as the Chinese cultural sphere expanded during the ancient period, it appears that many of the ethnic groups it absorbed maintained their native spoken language for many generations, and employed the Chinese written language for textual communication simply because it was the only written language available. /+/

“We are able to say that spoken ancient Chinese was largely a monosyllabic language: that is, the semantic (meaning) units of the language were almost always expressed by a single syllable. Each of these semantically significant syllables constituted a word. Words were uninflected: they did not take variable endings that indicated features such as tense, number, gender, or case. All these features, which make many Indo-European languages tedious to learn, are entirely absent from Chinese. No tense, no plurals, no subject-object markers. But it is disappointing to learn that a language stripped of all this complex features becomes not easier to master but harder. In ancient Chinese, which relies almost wholly on word order and a limited set of function words to provide grammatical clues to meaning, The level of ambiguity is spectacularly high. This is one of the reasons why many of the most revered ancient texts remain imperfectly understood.” /+/

Writing: A Pillar of Chinese Civilization

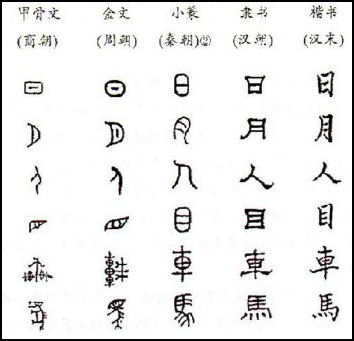

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Chinese characters are one of the world's most unique forms of writing. They reflect the perfect fusion of idea and image. Although cuneiform and hieroglyphics disappeared with the civilizations that produced them, Chinese has continued down to the present day, evolving into a beautifully aesthetic system of lines and dots the incorporates such calligraphic styles as seal, clerical, cursive, running, and standard script for visual appeal. Using the brush to create them results in one of the world's most beautiful forms of writing. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/ ]

“Writing is one of the pillars by which a civilization is judged. Words and the way they are written down also preserve many aspects of the culture that produced them by incorporating elements of time and space. The system of Chinese characters remains one of the most important threads that ties together its three thousand years of written history. Forms of ancient Chinese writing include: 1) oracle bone writing; 2) bronze writing bronze writing; and 3) writing on bamboo slips.Some of the more famous examples of these are: 1) bronze writing from Mao-pi Yi; 2) Bronze Writing from Sung Hu; 3) the Ch'u Bamboo Slips; and the Ch'u Bamboo Slips from Ching-meng Pao-shan. \=/

Evolution of Chinese characters

Forms of ancient Chinese script include: 1) Small Seal Script; 2) Clerical Script; 3) Running Script; 4) Standard Script and 5) Cursive Script. Some of the more famous examples of these are: 1) Small Seal Script from Mt. T'ai; 2) Clerical Script in the “Stone Gate Eulogy”’ 3) Running Script in the “Lan-t'ing Preface”; 4) Standard Script in the “Record of Niu Chueh”; and 5) Cursive Script in “Essay on Calligraphy.” \=/

“In China, writing before the Ch'in dynasty in the 3rd century B.C. evolved to become the clerical script of the Ch'in and Han dynasties, making these ancient forms difficult to decipher. At around 100 AD, Hsu Shen of the Eastern Han compiled "An Etymology Dictionary" of 9353 small-seal characters and included ancient forms or equivalents. This first effort at understanding ancient characters laid the foundation for the study of bronze inscriptions from the Shang and Zhou dynasties. "The Stone Classics in Three Scripts" from the 3rd century AD not only corrected characters in the Classics, but more importantly provided a link between contemporary and ancient writing. Deciphering Shang and Zhou bronze inscriptions has consistently relied on Hsu's dictionary. Even the discovery of script on unearthed oracle bones from the late Shang relied on his text. Just as important, however, oracle bone script has also made corrections to the dictionary itself. The study of ancient characters involves investigating the original appearance, addressing problems of pronunciation, and researching issues of meaning and grammar. \=/

Dr. Eno wrote: “Ancient Chinese was a language of great subtlety, enhanced by resonances which related written characters could produce.” In the story, “Han Qi Visits the State of Zheng”, set in the 6th century B.C., “ Han Qi’s comment about the “will of Zheng” employs two such resonances. The word for “poetry” in Chinese (shi) sounds like and uses a graphic element in common with the word for “will” (zhi u: “will” in the sense of “intent” or “purpose”). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

“There was, in fact, a saying current about the time that this narrative was composed to the effect that, “Poems speak one’s will.” The sense of the saying not only concerned the function of poetry, but also served as a gloss for the written character for “poetry,” which is composed of two graphs, one meaning “to speak,” and the other close to and homophonous with the graph for “will.” This notion of the “original” sense and function of poetry, as expressed by the written character, lay behind Han Qi’s initial request to learn the “will” of Zheng by hearing poetic recitations.” /+/

“Now, when Han Qi notes that the poems “have all reflected the will of Zheng,” yet another pun is involved. Because the word for “will” is written with the same character as a homophonous word meaning “record,” his statement is an elegant observation that both praises the way in which the ministers have conveyed the intent of their ruler, and equally points out that all of the poems selected by the ministers for this purpose are to be found among the recorded “Airs of Zheng.”“ /+/

Family Names, Genealogies and Rulers’ Titles in Ancient China

Character for the surname ren

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “In studying Chinese cultural history, nothing is more difficult than the fact that – just Chinese words in transcription tend to look alike to foreign readers – Chinese names, when written without characters, are far more similar to one another than is the case in Western countries. The most important rule in dealing with Chinese names is this: the surname precedes the personal name. For example, the Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Zedong was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Mao, who gave him the name Zedong. This order always holds in a Chinese context, although some Chinese, when abroad, may reverse the order to conform with non-Chinese norms. Dr. Eno wrote: “In ancient China, surnames were possessed only by those patrician families who played significant social roles. While some clans seem to have possessed surnames from a very early date, we still see at a late date rulers creating new clans through the bestowal of surnames, which was a great honor. Qi, by receiving a surname, now became the head of a clan (whereas before, according to the myth, he would have been a man without any clan status whatever, his father being a footprint without social standing). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/]

“By granting Qi an estate, Shun also assured his clan of membership in the patrician elite, as each generation of subsequent clan heads would inherit the title of the ruler of Dai. The surname of the Zhou ruling house was, indeed, Ji, as the text states. The skeptical historian will suppose that this account of the origins of the Ji clan was an invention devised sometime near the date of the Ji clan’s conquest of the Shang (whose grand progenitor Xie was also a legendary minister to Shun), to glorify their history and present themselves to the various clans of China as worthy successors to the Zi clan, which had provided the rulers of the Shang. /+/

“In general, rulers are known in the histories by a posthumous title which gives their rank and adds one of a relatively short list of honorifics. “Wen”, which means “patterned,” “cultivated,” or “refined,” is such an honorific. Its assignment to King Wen indicates that it was he who brought the Zhou people most decisively into the Zhou cultural sphere. Since the posthumous title and basic legends of King Wen are attested to from the start of the Zhou kingdom, it may be that many of sinicizing features here attributed to the Old Duke’s reign were originally understood to have been the work of King Wen.” /+/

Chinese Time: a History of Dynasties

According to “Countries of the World and Their Leaders”: China is the oldest continuous major world civilization, with records dating back about 3,500 years. Successive dynasties developed a system of bureaucratic control that gave the agrarian-based Chinese an advantage over neighboring nomadic and hill cultures. Chinese civilization was further strengthened by the development of a Confucian state ideology and a common written language that bridged the gaps among the country's many local languages and dialects. Whenever China was conquered by nomadic tribes, as it was by the Mongols in the 13th century, the conquerors sooner or later adopted the ways of the “higher” Chinese civilization and staffed the bureaucracy with Chinese. The last dynasty was established in 1644, when the Manchus overthrew the native Ming dynasty and established the Qing (Ch’ing) dynasty with Beijing as its capital. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

Dr. Eno wrote: “The Western world has a tradition of viewing historical time as a linear progression. We number our years consecutively, and easily conceptualize past eras in terms of centuries, succeeding one another as a type of narrative flow. Until the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, the governments of Chinese history had all been led by kings or emperors, whose thrones were passed down on the principle of hereditary succession within a single, ruling family: a “dynasty.” The history of China before 1912 has traditionally been conceived in terms of a succession of dynasties – rulers of China passing their thrones to their sons through the generations, until the authority of the ruling family is undermined by serious misrule or military weakness, and a challenger’s armies conquer the government, installing a new “dynastic founder,” who begins the process again. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University/+/ ]

“Time was traditionally bound to the ruler. Each new ruler has begun the calendar anew, proclaiming a new “first year” upon the year of his (or, in a single celebrated case, her) accession. Years and dates did not reflect a notion of progressive time – a march towards “the future”; rather, time itself was inseparable from the ruler, whose edicts controlled the calendar. For millennia, rulers of China would exploit this tie by proclaiming new starts to the calendar even in the midst of their own personal reigns, as a way of wiping away past mistakes or launching new policy regimes. /+/

“Historical time was understood through a line of succession – the list of dynasties that had ruled China. Because there were periods of time where China was, in fact, not ruled as a single country by a single ruler, this line of dynasties, when listed in full detail, could be rather complex. However, it was – and still is – common when speaking of China’s past to refer to these periods of disunity by titles such as “the period of the Six Dynasties,” and so forth, and in this way, the three thousand year course of traditional Chinese history is often represented as a succession of just ten major dynastic houses.”

Major Dynastic Periods of Traditional Chinese History

Yellow Emperor, China's legendary first emperor

Pre-imperial Shang c. 1500 – 1045 B.C.

Zhou 1045 – 256 B.C.

Imperial Qin 221 – 208 B.C.

Han 206 B.C. – AD 220

“Six Dynasties” 220 – 589

Sui 589 – 617

Tang 618 – 907

“Five Dynasties” 907 – 960

Song 960 – 1279

Yuan 1279 – 1368

Ming 1368 – 1644

Qing 1644 – 1911

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ The first two dynasties were ruled by “kings” (to translate the Chinese term into its rough English equivalent), whose power was somewhat limited, and whose “kingdoms” were significantly smaller than contemporary China. Beginning in the year 221 B.C., however, the greater part of today’s China was unified and then expanded under an enormously powerful but short-lived ruling house, the Qin (pronounced “chin,” from which the word “China” is derived). From this time, China is considered to have become an empire, ruled by an “emperor,” a title which translates a grandiose term coined for himself by the founder of the Qin, a man known to history as “the First Emperor.” [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“When people in China think of time in the distant past, they don’t think of it in terms of this or that century; they think back to dynasties. Each dynasty has a narrative of events and outstanding people, as well as a distinctive cultural character, and this makes Chinese cultural history, despite its great length, something that can be conceptualized with relative ease.” /+/

See Separate Article CHINESE DYNASTIES AND RULERS factsanddetails.com

Sixty-Year Cycles of Traditional Chinese Time

Dr. Eno wrote: “Although the annual calendar of early China underwent constant revision and years were always calculated relative to political rhythms, there was nevertheless one form of absolute timekeeping that, from Shang times to the present, has persisted unbroken. This is a sixty-day or sixty-year cyclical system, generated by the ordered succession of two series of ordinal signs, known as the ten heavenly stems and the twelve earthly branches. By matching, in sequence, the elements of the set of ten with the set of twelve, a sixty unit series is generated, organized in six units of ten. In this passage, the term "wu-wu"represents such a stem-branch combination (the two “"wu"s,” though homophones, are different characters). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“In ancient China, each day could be designated by a reign year, a month of the lunar calendar, and a day of the month, but it was also designated independently by a stem-branch cyclical sign, which showed its place within the sixty day sequence. Some aspects of daily life, such as sacrificial schedules, were based on the ten-day rhythm of the heavenly stems, which may be thought of as a type of week. (Months and years also received cyclical sign designations, although the earth-branch set of twelve figured more importantly there. The well-known Chinese animal-year cycle simply represents the earthly branches associated with corresponding animals.) Issues of fortune telling, a major concern of traditional China, were closely tied to the cyclical signs, which were considered to have deep mantic significance. /+/

“The stem-branch series of signs is linguistically very puzzling, and there are some scholars who believe that it is of non-Chinese origins. There are several other very unusual such sets associated with calendrical and astronomical terminology which also are suggestive of diffused cultural influences, perhaps from Central Asia or Mesopotamia.

See Separate Article CHINESE LUNAR CALENDAR AND CHINESE ACCOUNTING OF TIME factsanddetails.com

Sexagenary cycle

Historical Dating and Calendars in Ancient China

Dr. Eno wrote: “In traditional China, there was no system of dating years in an unbroken, consecutive stream. Years were noted according to their location within the reigns of specific kings. One sign of the legitimacy of a ruler is whether or not chronicles date events according to his reign. A new ruler, properly a king, but during the eras of disunity of the late Zhou sometimes simply any patrician lord, would often upon assuming the throne issue a calendar in his name. This was often not an empty gesture. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The basic calendrical system of ancient China was a rather unstable solar-lunar year, calculations for which were complex and difficult. Calendars frequently moved far from synchronization with the natural rhythms of the seasons and the stars, which could disrupt agricultural planning (with devastating effects on the economy), confuse the systems of religious sacrifice, and make political activity chaotic – imagine a state where not only clocks but even calendars were not synchronized trying to map out a prolonged military campaign! /+/

“Earlier, Sima Qian’s narrative noted as one of King Wen’s accomplishments that he adjusted the Zhou calendar: this was a significant political act standardizing a basic social measure. Now, when Sima Qian begins to date events according to the elapsed years from King Wu’s accession, he is sending a strong signal that the locus of legitimacy in the Chinese cultural sphere had, from this point on, effectively shifted from the Shang king to the lord of the Zhou people.” /+/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021