SHANGHAI

Shanghai Is the largest, richest and most cosmopolitan city in China. Built on mud flats of the Whangpo River, about 20 kilometers up the Yangtze from the Pacific Ocean, it is home to about 20 million people — a remarkable number when you consider it has only been around for about 160 years. The “hai” in Shanghai means ocean.

Shanghai is most populous city in China and the third most populous city in the world with 24.3 million people (2019) in municipality and 34 million in the metro area. Called “hu” or “shen” for short, and located where the Yangtze River empties into the sea, serving as a gateway to the Yangtze River valley, Shanghai is a municipality directly under the central government. It has an area of 6,340 square kilometers is the major financial, trade and shipping center of China.

Regarded by many as more of a business center and a fashion statement than a tourist destination, Shanghai doesn't have as many tourist sights as Beijing but it has a vibrancy and intensity that makes the rest of China seem like it needs a shot of whiskey and a battery recharge to catch up. Communism isn’t very visible. People seem more interested in striking deals, looking good and getting a hold of the latest stuff. A sign outside the airport reads; “Welcome to Stylish Shanghai.”

Andrea Sachs of the Washington Post described Shanghai as “an economic renegade....dialed to high speed, trying to be the first to reach some undefined finish line. Drivers disregarded speed limits and red lights, pedestrians move with the force of an undertow, futuristic building materialize nearly overnight.” Shanghai is a municipality like Beijing, Tianjin and Chongqing. The old parts of town are a mix of European buildings, crowded working class neighborhoods, and vast expanses of drab buildings, smokey industrial complexes and manufacturing centers.

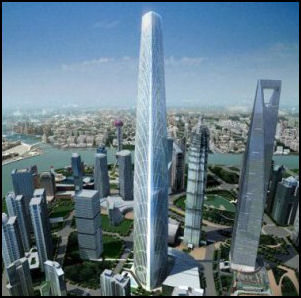

New Shanghai is a city of striking skyscrapers, pedestrian-hostile roads, modernist transportation, and smoke-filled, hazy skies. The impressive skyline grows higher and become more surreal every day, filling up with futuristic architecture that makes it look like something out of Flash Gordon, The Jetsons or Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

By some counts Shanghai is the world’s fastest-growing city. It sprawls like Los Angeles but is dense like Manhattan and has had more than 10,000 high-rise buildings constructed in it in the past quarter century. From the sky neatly-arranged, apartment blocks that look like rows of oblong houses go on and on and on.

Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing are direct-administered municipalities — municipalities under the direct administration of the central government in Beijing and have the same rank as provinces. A municipality is a "city" (“shì”) with "provincial" (shěngjí) power under a unified jurisdiction. As such it is simultaneously a city and a province of its own right. A municipality is often not a "city" in the usual sense of the word term but instead is an administrative unit with a main central urban area at its core and much larger surrounding area containing rural areas, smaller cities (districts and subdistricts), towns and villages. Books: “Shanghai: The Rise and Fall of a Decadent City” by Stella Dong HarperCollins, 2000; “Global Shanghai 1850-2010: A History in Fragments” by Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, Routledge (New York), 2009; Book: “Shanghai Future: Modernity Remade” by Anna Greenspan Oxford University Press, 2014. "Shanghai" by Harriet Sergeant (John Murray, 1998) is an interesting and readable account of Shanghai's colorful history.

Web sites: Smarts Shanghai smartshanghai.com ; Shanghai China ; Travel China Guide travelchinaguide.com ; Wikitravel wikitravel.org Maps Joho Maps Joho Maps ; China Highlights chinahighlights.com ; Subway Maps: Joho Maps johomaps.com

Climate in Shanghai

Shanghai has a humid subtropical climate and experiences four distinct seasons. Winters are chilly and damp, and cold northwesterly winds from Siberia can cause nighttime temperatures to drop below freezing, although most years there are only one or two days of snowfall. Summers are hot and humid, with an average of 8.7 days exceeding 35 °C (95 °F) annually; occasional downpours or freak thunderstorms can be expected.

Shanghai is situated on the same latitude as northern Florida and has a similar climate. Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! From May to September temperatures are around 20°C (68°F), June through August is both the rainy season and the hottest time of year in Shanghai. Temperatures above 30°C (86°F) coupled with the rain make Shanghai a steamy sauna during the summer. The coldest days of winter in Shanghai hover around 0°C (32°F). Every three years, Shanghai gets a good sprinkle of snow that lasts long enough to cause chaos on the roads. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Shanghai sits on the edge of southern China, which is affected most by the monsoon season known to Chinese as the "plum rain season" and is dominated by the Bai-u front. In most places the monsoon season extends from June to September . In some places it begin in May. The Bai-u front brings seasonally heavy rains in June and July. The typhoon season is from July to October. The typhoons that strike southern China come in from the Pacific and South China Sea and are usually characterized more by their heavy rains than high winds. The ones that strike Shanghai typically blow in from Taiwan and leaves behind clear blue skies.

The most pleasant seasons are Spring, although changeable and often rainy, and Autumn, which is generally sunny and dry. The city averages 4.2 °C (39.6 °F) in January and 27.9 °C (82.2 °F) in July, for an annual mean of 16.1 °C (61.0 °F). Shanghai experiences on average 1,878 hours of sunshine per year, with the hottest temperature ever recorded at 40.6 °C (105 °F) on 26 July 2013, and the lowest at −12.1 °C (10 °F) on 19 January 1893.

Shanghai is susceptible to typhoons in summer and the beginning of autumn, none of which in recent years has caused considerable damage. The City's average elevation is 4 meters (13 feet) above sea level. Lower lying areas are vulnerable to flooding during prolonged regional rains, typhoons, tropical storms and storm surges. Severe flooding may close roads and halt all transportation.

Life in Shanghai

Jin Mao Tower and

Shanghai World Financial Center

On the ground, especially in the city center, Shanghai is a intense, sensory place with little space. Sidewalks and markets are filled with vendors selling all kinds of things; the aroma of seafood, snacks and cakes being deep fried in oil permeates the air; almost everywhere you look there are huge crowds. In the backstreets many people live, crowded with several families in 100-year-old “shikumen” designed for a single family. Since there often isn't enough buildings to house everyone and their businesses people treat the streets as their living rooms and sidewalks as commercial space.

Shanghai is regarded as more livable and less ugly than Beijing. The pollution isn’t quite so bad and the development hasn’t been quite so reckless. There are lots of trees and enough water and an effort has been made funnel people on to subways rather than cars. Critics claim Shanghai is on the road to becoming like Singapore and lacks the intellectual and cultural vibrancy of Beijing. Some people really don’t like Shanghai. The actor Ralph Fienes told the Times of London. “I thought it was a place gone mad with retail commerce, with everyone working their asses off to sell, sell, sell. I thought Shanghai has an exciting energy initially. After a while it gets to you, and I found it a bit oppressive, all that manic craziness to build the modern world ad nauseam.”

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Every city has a rhythm, a pulse that makes it move. In Shanghai, one of the fastest growing megacities in the world, it's easy to get lost in the relentless percussion of jackhammers and pile drivers, bulldozers and building cranes. The proliferating skyscrapers and construction sites are part of a stunning metamorphosis that Shanghai showed off as host of Expo 2010...The rise of China's only truly global city, however, is driven not by machines but by an urban culture that follows its own beat — embracing the new and the foreign even as it seeks to reclaim its past glory." [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010]

Shanghai Population

Shanghai is the most populated city in the most populated country in the world. It is the third most populous city in the world behind Tokyo and Delhi, with 24.3 million people (2019) in municipality which covers 6,341 square kilometers (2,448 square miles) and 34 million in the metro area. The population density of Shanghai is 3,800 people per square kilometer(9,900 per square mile). [Source: Wikipedia]

David Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Over the past decade or more, Shanghai has grown like no other city on the planet. Home to 13.3 million residents in 1990, the city now has some 23 million residents (to New York City’s 8.1 million), with half a million newcomers each year. To handle the influx, developers are planning to build, among other developments, seven satellite cities on the fringes of Shanghai’s 2,400 square miles. Shanghai opened its first subway line in 1995; today it has 11; by 2025, there will be 22. In 2004, the city also opened the world’s first commercial high-speed magnetic levitation train line. [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

In the mid 2000s, Shanghai was the fifth most populated city in the world. Only Tokyo, New York, Sao Paulo and Mexico City were larger. There were 8 million people in Shanghai city and 19 million in the Shanghai municipality, plus an additional two to three million unregistered migrants, most of them rural people who had moved into shanytowns and slums, and worked primarily in the service and construction industries. Shanghai grew from 4.3 million in 1950 to 15 million in 2000. The number of foreign visitors to Shanghai was 4 million in 2004 , about half of them tourists and half of them business travelers.

People from Shanghai

The people of Shanghai are considered "blunt, offhand, and presumptuous.” Traditionally more worldly, Westernized and wealthy than other Chinese, they like their food cooked in rapeseed oil and view themselves as different from other Chinese, who they sometimes dismiss as still living in the Stone Age. The Shanghainese, as the city's residents are known, speak their own distinctive dialect — some say it's a separate language — and are recognized as being among the country's most able businessmen. The rapid Shanghai dialect is difficult for those outside the city to understand.

Some have compared Shanghainese to New Yorkers. Both carry themselves with haughty superiority and share a sort of "it-stinks-but-its-great" attitude about their cities. One Hong Kong banker said the Shanghainese "have a strong sense of self-importance." Both Shanghai and New York have traditionally been regarded as places where one can find anything: the latest fashions, the best food, drugs, girls...and boys.

Other have compared Shanghai people with Singaporeans. Peter Kwan, a professor of Asian American studies at Hunter College, wrote in the New York Times, “the people of Shanghai, whether rich or poor, have always regarded themselves to be more rational and efficient than their countrymen. They have always reproached the people of Beijing for talking about politics, while they themselves got things done. They are especially proud of their trademark way of doing things — the so-called haipai style.”

The Shanghai-based writer Wang Anyi told Newsweek: “Shanghai people have a long tradition of following the rules. Beijing people are a bit wild and grandiose.” People from Shanghai live to an average of 76.5 years, about 6½ years longer than the people from the rest of the country. The mayor Shanghai told the Washington Post that the reason for this is that they do tai chi exercises every morning and go to bed before 10 every night.

On his effort to make conversation with some prospective clients, California architect Robert Steinberg told Smithsonian magazine: “I was trying to make polite conversation and started discussing some political controversy that seemed important at the time. “One of the businessmen leaned over and said, ‘We’re from Shanghai. We care only about money. You want to talk politics, go to Beijing.’ On the pace in the city, he said “We talk acres in America; developers here think kilometers,” he said. “It’s as if this city is making up for all the decades lost to wars and political ideology.” [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

At the time of the Olympics, Shanghaiese tried to portray themselves as more warm-hearted and compasionate. In the autumn of 2007 Shanghai hosted the Special Olympics. More than 1,200 of the 8,000 athletes that participated were Chinese. Chinese President Hu Jintao presided over the opening ceremony. To promote the events billboards with happy-faced special athletes and signs with characters for “civilization,” “humanism” and “love” were post all over town. The Shanghai mayor said the point of hosting the Special Olympics was to help create “a civilized and harmonious environment for all.”

Life in Shanghai’s Lilongs and Shanghai’s ‘Street of Eternal Happiness, ’See Separate Article URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

History of Shanghai

opium

Shanghai is not particularly known for its ancient history. One noodle shop owner told the Washington Post, “If you want to see 2,000 years of history, you go to Xian. If you want 500 years of history, go to Beijing. If you want to know what will happen, you go to Shanghai.” Up until 1842 Shanghai was just a small fishing village. After the Opium Wars (1839-42) and the bombardment of the Chinese fort at Huangpu by the British man-of-war “Nemesis”, the British coerced the Chinese into making Shanghai a "treaty port" with a self-governing British district called a concession. Quick on the heels of the British came sizable populations of Americans, French and Russians. By the 1850s, Shanghai had a community of 60,000 expatriates, most of whom lived in separate concessions which were divided along national lines. In 1863, the British and Americans merged their territory into the International Concession.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “In the beginning it was a foreign dream, a Western treaty port trading opium for tea and silk. The muscular buildings along the riverfront known as the Bund (a word derived from Hindi) projected foreign, not Chinese, power. From around the world came waves of immigrants, creating an exotic stew of British bankers and Russian dancing girls, American missionaries and French socialites, Jewish refugees and turbaned Sikh security guards.

To serve the international community and seek their own fortune many Chinese moved to Shanghai. A busy harbor carried out about half of China's foreign commerce. Goods from the interior of China came via the Yangtze River. Suzhou Creek linked Shanghai to the Grand Canal. Railways were built that linked Shanghai to Beijing and other parts of China and the world. . Known as both the "Whore of Asia" and the "Paris of Asia," late 19th-century Shanghai boasted fine restaurants, exquisite craft shops, backstreet opium dens, gambling parlors and brothels with names like "Galaxy of the Beauties" and "Happiness Concentrated." In the 1920s, foreigners played polo and enjoyed dog racing and horse racing. By the 1930s, Shanghai was the largest trading center in Asia, among the ten largest cities in the world, arguably the most decadent place on the planet, and a city so westernized, it had its own Chinatown. By some counts one in 20 women worked as prostitutes and Western taipans and Chinese compradores amassed huge fortunes, engaged in intrigues and plots and threw lavish parties.

Japanese attack in 1937

Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “It was like no other place on Earth: a mixed-blood metropolis with a reputation for easy money — and easier morals. The British, French, and Americans built gracious homes along tree-lined streets. Local shops carried the latest fashions and luxuries. The racecourse dominated the center of town, while the city's nightlife offered everything from dance halls and social clubs to opium dens and brothels.

The whole enterprise, however, rested on the several million Chinese immigrants who flooded the city, many of them refugees and reformers fleeing violent campaigns in the countryside, beginning in the mid-1800s with the bloody Taiping Rebellion. The new arrivals found protection in Shanghai and set to work as merchants and middlemen, coolies and gangsters. For all the hardships, these migrants forged the country's first modern urban identity, leaving behind an inland empire that was still deeply agrarian. Family traditions may have remained Confucian, but the dress was Western and the system unabashedly capitalist, and the favorite soup, borscht, came from Russians escaping the Bolsheviks. "We've always been accused of worshipping foreigners," says Shen Hongfei, one of Shanghai's leading cultural critics. "But taking foreign ideas and making them our own made us the most advanced place in China."

The Japanese occupied Shanghai from 1937 to 1945. In that time, Shanghai was the only city in the world that did not require a visa and was sort like Asia’s answer to the Casablanca, attracting thousands of displaced people, from all over the world, including Jews fleeing Nazi Germany and white Russians fleeing the Russian Revolution. After the Communist takeover in 1949 about 2 million people from the countryside moved into the Shanghai. There was not enough jobs, food or housing for them so the government shipped about a million of them to farms, public works projects and industrial zones. "China's socialist overlords" Larmer wrote, "made Shanghai suffer for its role as a modern-day Babylon. Besides compelling the economic elite to leave and suppressing the local dialect, Beijing siphoned off almost all the city's revenues. The Communists changed Shanghai dramatically. Addicts and prostitutes were given the choice of cleaning up their act or being shot. Trade collapsed. Businesses fled — many to Hong Kong — or were taken over. The government made Shanghai into a manufacturing center for textiles, steel, heavy machinery, ships and oil refining When China's economic reforms began in the 1980s, Shanghai had to wait nearly a decade to join in. "We kept wondering, When is it going to be our turn?" Huang Mengqi, a fashion designer and entrepreneur who owns a shop off the Bund, told National Geographic. In 1991 Deng Xiaoping finally decided that Shanghai should be a showcase for the progress made by China with its economic reforms. Between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, Shanghai went from being a drab socialist city into a modern capitalist metropolis. [Source:Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010, Fro more, See History, History in the 19th Century, Foreigners and Chinese in the 19th Century also See Culture, Film, Chinese Film Industry

See Separate Article HISTORY OF SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com

Shanghai Economy and Business

In the late 2000s, about five percent of China’s GDP is generated in Shanghai and 20 percent of its exports — a 500 percent increase from 1992 — pass through its ports. New businesses open at a rate of five an hour and growth rates of 8 or 9 percent a year are considered disappointing. Shanghai accounts for 2 percent of China’s population but also accounts astounding 20 percent of China’s property value. In 2006, 1 million homes — half the of housing starts in the United States in 2004 — were under construction

The Shanghai metropolitan area (including the suburban counties) is a financial, commercial, educational, industrial, technology, shipping and transport center. It has several Development Zones, each dedicated to specific industries. Shanghai is a still a hub industries — though less than before — such as iron and steel, shipbuilding, textiles and garments, electronics, clocks, bicycles, automobiles, aircraft, pharmaceuticals, computers, publishing, and cinema. Shanghai is China's largest port and most important foreign trade center. Shanghai itself accounts for 8 percent of all Chinese exports but handles nearly two-thirds of China's total exports through its ports. Once the world's third-largest port, Shanghai remains China's principal shipping center. [Source: Cities of the World, Gale Group Inc., 2002, adapted from a December 1996 U.S. State Department report]

In the Mao era, members of the old Shanghai elite who remained in China had their money taken away and were hounded by Red Guards. Deng Xiaoping deliberately promoted economic development in Shenzhen, Guangzhou the Pearl River and excluded Shanghai in the 1980s concerned about Shanghai’s potential as an economic power and worried about what might have happen if the economic reforms failed. In Shanghai was not really open up economically until 1991, after Tiananmen Square, when Beijing wanted to appease popular discontent there by distracting them with the potential to make money, and picked up momentum when Jiang Zemin and Zhu Ronji, two former Shanghai mayors, became Chinese leaders,. Once cut loose Shanghai took little time to catch up. To attract foreign investment it offered cheap office space, tax breaks and promised of minimal red tape. Foreigners came in droves. Within 15 years Shanghai had surpassed Shenzhen and thr Pearl River Delta as China’s primary industrial zone The scale of development Shanghai has experienced has been enormous and been compared to the rebuilding of Japan and Europe after World War II. Billions of dollars has been spent on public works programs, new office towers, hotels, shopping centers and factories. A 208-square-mile industrial development called the Pudong was built with some of the world’s highest skyscrapers and billion-dollar auto and steel plants. The Chinese government wanted Shanghai to surpass Hong Kong as a trading center in the early 2000s and become the trade and banking center of the whole world in the 2010s As of 2006, the United States has invested more $6 billion in the Shanghai area and imports at least $25 billion in products from the region annually. U.S. companies with major research centers in Shanghai include DuPont, Rohm & Haas and General Electric. IBM and Intel are among the companies that have established their Asian headquarters and major manufacturing operations in Shanghai.

Shanghai in the 1920s

Shanghai Development

Shanghai often seems like one huge construction project and most of what is completed was built in the last 30 years. More than 27,000 companies have participated in 20,000 projects, including 3,000 high rises, and 5,000 major projects like new bridges, tunnels, ring roads and public housing. Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in ““CultureShock! China”: Imagine living in a city where if you forget to pick up your dry cleaning for just a week, you run the risk of losing it forever because the block the Laundromat is located on is slated that week for demolition. In 1995, that was the risk that you ran of forgetting your dry cleaning for more than a few days in Shanghai. Twenty-five percent of the construction cranes in the world were in Shanghai. Imagine living in a city where the day you arrived, the place known as Pudong was a single-standing TV tower, grandiosely called ‘The Pearl of the Orient’, which looked like a cross between a Jetson’s space home and a series of onions skewered on a stick, standing amid farmland and rundown wood shacks. A mere six years later, that same TV tower was surrounded by a shining city of iconic architecture, inhabited by millions. [Source:“CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, "Shanghai's moment has arrived. Fueled by years of growth faster than China's as a whole — and a culture now unshackled and dealing comfortably with the outside world — the city is eager to recapture the glories of the past, only this time on its own terms. Twenty years ago the European buildings on the Bund stared across the Huangpu River at low-lying farmland dotted by factories; today that same land bristles with skyscrapers, including the 101-story World Financial Center. All told, the city has added more than 4,000 high-rises. For a place once dominated by rickshaws and bicycles, the most extraordinary statistic may be not vertical but horizontal: nearly 1,500 miles of roads in and around Shanghai that did not exist a decade ago." [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010]

Anna Greenspan wrote in “Shanghai Future: Modernity Remade”: “China is in the midst of the fastest and most intense process of urbanization the world has ever known, and Shanghai — its biggest, richest and most cosmopolitan city — is positioned for acceleration into the twenty-first century. Yet, in its embrace of a hopeful — even exultant — futurism, Shanghai recalls the older and much criticized project of imagining, planning and building the modern metropolis. Today, among Westerners, at least, the very idea of the futuristic city — with its multilayered skyways, domestic robots and flying cars — seems doomed to the realm of nostalgia, the sadly comic promise of a future that failed to materialize. Shanghai Future maps the city of tomorrow as it resurfaces in a new time and place. It searches for the contours of an unknown and unfamiliar futurism in the city’s street markets as well as in its skyscrapers. For though it recalls the modernity of an earlier age, Shanghai’s current re-emergence is only superficially based on mimicry. Rather, in seeking to fulfill its ambitions, the giant metropolis is reinventing the very idea of the future itself. As it modernizes, Shanghai is necessarily recreating what it is to be modern.” [Source: “Shanghai Future: Modernity Remade” by Anna Greenspan Oxford University Press, 2014]

Shanghai fascinates urban planners because it is already huge and is still growing at an amazing pace and has lots of money to play with. The amount of living space per person in Shanghai has grown from 8 to 16 square meters between 1990 and 2008. This means that not only is the city growing at an amazing pace in term of numbers these numbers they are also growing in terms of the space they need. Shanghai residents are proud of their city’s explosive growth. Huge skyscrapers have gone up in the business center. Massive concrete pylons rise from densely-populated neighborhoods for elevated highways that snake through the city and converge at the Yanan Road flyover. The mix of futurist skyscrapers and garish shopping complex have made Shanghai a popular location for movies set in the 22nd century.

History of Shanghai Development

Shanghai skyscrapers Much of the city’s development was launched by former mayor and leader Zhu Rongji. In the 1990s $1 billion was authorized for a "green belt" beautification program and $24 billion was allocated to build a subway system, a second international airport, a container port, more tunnels, freeways, railroads, and water and sewer facilities. In the late 1990s, according to some estimates, Shanghai was the site of 10 percent of the world's commercial construction projects. As of 2006, there were 4,000 skyscrapers in Shanghai, nearly double the number in New York City, with another 1,000 due to be completed in the next ten years.

Among trophy projects that have recently been completed are the Hangzhou Bay Bridge, the world’s longest sea bridge, which opened in 2008; the 1,088-meter-long, $846 million Sutong Bridge, the longest cable-stayed bridge, which opened over the Yangtze River less than 300 kilometers away in 2008; and the space-age magnetically levitated train, which began operating in 2004 Shanghai spent $2.5 billion on the Expo in 2010 and invest another $12 billion in infrastructure related to the project and in the process relocate tens of thousands of more people.

David Devoss wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Shanghai’s makeover began haphazardly — developers razed hundreds of tightly packed Chinese neighborhoods called lilongs that were accessed through distinctive stone portals called shikumen — but the municipal government eventually imposed limitations on what could be destroyed and built in its place. [Source: David Devoss, Smithsonian magazine, November 2011]

“Materialism, of course, comes with a cost. A collision of two subway trains” in September 2011 “injured more than 200 riders and raised concerns over transit safety. Increased industry and car ownership haven’t helped Shanghai’s air; this past May, the city started posting air-quality reports on video screens in public places. Slightly less tangible than the smog is the social atmosphere. Liu Jian, a 32-year-old folk singer and writer from Henan Province, recalls when he came to the city in 2001. “One of the first things I noticed was there was a man on a bicycle that came through my lane every night giving announcements: ‘Tonight the weather is cold! Please be careful,’” he says. “I had never seen anything like it! It made me feel that people were watching out for me.” That feeling is still there (as are the cycling announcers), but, he says, “young people don’t know how to have fun. They just know how to work and earn money.” Still, he adds, “there are so many people here that the city holds lots of opportunities. It’s hard to leave.”

“Even today, Shanghai’s runaway development, and the dislocation of residents in neighborhoods up for renewal, seems counterbalanced by a lingering social conservatism and tight family relationships. Wang, the business reporter, who is unmarried, considers herself unusually independent for renting her own apartment. But she also returns to her parents’ house for dinner nightly. “I get my independence, but I also need my food!” she jokes. “But I pay a price for it. My parents scold me about marriage every night.”

“In a society where people received their housing through their state-controlled employers not so long ago, real estate has become a pressing concern. “If you want to get married, you have to buy a house,” says Xia, the wine seller. “This adds a lot of pressure”—especially for men, she adds. “Women want to marry an apartment,” says Wang. Even with the government now reining in prices, many can’t afford to buy. Zao Xuhua, a 49-year-old restaurant owner, moved to Pudong after his house in old Shanghai was slated for demolition in the 1990s. His commute increased from a few minutes to half an hour, he says, but then, his new house is modern and spacious. “Getting your house knocked down has a positive side,” he says.

Demolition and Preservation in Shanghai

Around 5 million square meter of property is demolished each year to make way for new buildings, parks, highways and residential area that house people more efficiently. Entire neighborhoods with Ming, Qing and Republican-era buildings have been leveled by bulldozers and wrecking balls to make room for modern office building. Classic buildings have been given horrible renovations.

The 70-year-old sycamores that once lined the colonnade on the Bund have been torn down to make way for a pedestrian esplanade; new development. The old city of walk-up buildings and vibrant street life is being replaced with expensive high rises, underground parking garages and closed door nuclear families. Hundreds of thousands of people if not millions have been relocated.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, ‘Shanghai's old neighborhoods are disappearing. In 1949 at least three-quarters of Shanghainese lived in lilong; today only a fraction do. Two lilong adjacent to Baoxing Cun have been demolished, one to make room for an elevated highway, the other for a power switching station to light up Expo 2010. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010]

Today the ladies' banter is darkened by speculation. "We keep hearing we're next in line for demolition," Jin says. For many Shanghainese, the decades of neglect and overcrowding have turned the lilong's intimacy into something more like asphyxiation. But Jin worries that the razing of Baoxing Cun will scatter her friends to distant suburbs. "Who knows how much longer we have?" she asks.

“Shanghai has taken more care than most Chinese cities to preserve its historic architecture, sparing hundreds of pre-Communist-era mansions and bank buildings from the wrecking ball. Yet only a few lilong appear on the list of protected areas. Ruan Yisan, a professor of urban planning at Tongji University, is waging a campaign to save these living repositories of Shanghai culture. "The government should demolish poverty, not history," he says. "There's nothing wrong with improving people's lives, but we shouldn't throw our heritage away like a pair of old shoes." Not long ago a government work crew swooped in to splash Baoxing Cun with a fresh coat of cream-colored paint. The Potemkin makeover does little to conceal the neighborhood's dismal condition. Nevertheless, Jin is happy to know that, at least until after Expo 2010, Baoxing Cun will not be torn down. "Here," she says, as a bare-bellied neighbor listens in, "it's all like family."

Shanghai Architecture, Infrastructure and Port

Owen Hatherley wrote in the The Guardian, “In contemporary Shanghai, architectural styles all coincide — the crassest postmodern revivalism and the purest ascetic modernism. You see innumerable blocks of flats clad in neoclassical or neogothic detail, but they're arranged in the geometrically ordered towers-in-parkland style of 1950s high modernism, invariably with south-facing aspect. You find vertiginous skyscrapers treated as objects of national pride that were developed by and bear the logos of Japanese or Taiwanese capital. Some old neighbourhoods — whether the Tudorbethan villas built for French and British colonials and the indigenous bourgeoises, or the ultra-dense Lilong courtyard housing built for the Chinese masses — are restored to the point of sanitization, some are rotting or demolished, others are reconstructed afresh. [Source: Owen Hatherley, The Guardian, October 31, 2010]

At the same time, a high rise boom creates a precipitous, sometimes unnerving and sometimes thrilling new landscape. This too is the product of contradiction — the pinnacles at the top of each tower are not pure capitalist spectacle but the result of state planning edicts, to stop extra floors being built on top.

There is green infrastructure, in the form of an extensive metro system built at lightning speed, and a Maglev train — though the latter goes only from the Pudong business district to the less-than-green airport. Simultaneously, the city erects the most astonishing, Cyclopean multi-level expressways to induce people off bikes and into SUVs.

The megalopolis at the center of the Yangtze river delta, whose factories, refineries and power stations are going at full pelt, creating a charred, apocalyptic industrial maelstrom, suffers nowadays from the consequences of deindustrialization, with numerous inner-city industrial structures ripe for creative reuse. All this raging tension is supposedly harmonious. It is fitting, in a society that still claims to cling to socialist values, while enforcing a spectacularly exploitative primitive accumulation.

The first phase of huge new container port — the Yangshan Deep Water port — opened in Shanghai in December 2005 on an island 32 kilometers out to sea and connected to the mainland by a 30-kilometer six-lane bridge, one of the longest in the world. The bridge alone took 2½ years and 6,000 workers to build. When the port is complete it will be the largest container shipping port in the world, able to handle 20 million containers a year. It is expected to be completed in 2010 at a cost of around $20 billion. Many predict when this port is in full operation Shanghai will overtake Hong Kong and Singapore as the world’s largest port. . As of 2009, the port in Shanghai was the world’s busiest. It has experienced 20 percent growth through much of the 2000s and aims to become a full-service, world-class shipping center by 2020 complete with “software” that it lacks now such as ship financing, reinsurance of ships and arbitration. The centerpiece of the expansion will be the Yangshan Deepwater Port, which is connected to the mainland via a 32.5-kilometer bridge. The shipbuilding facility on Changxingdao Island near Shanghai were finished in the fall of 2008. It is one of the world’s largest shipbuilding sites.

Shanghai Traffic and Pollution

Shanghai has its share of environmental problems. It is often shrouded in smog, with cars accounting for 70 percent to 80 percent of the air pollution Describing a sunny day in Shanghai, the journalist Allen Abel wrote, “the sky is the color and density of oatmeal, feebly lit by an orange disc as vague as a watermark.” Sometimes the smog is so bad you can't see the street from a forth floor window.The Huang Po River and Suzhou Creek stink of human waste, factory chemicals and effluence from pig farms; and the majority of homes still don't have flush toilets. There has been so much development that parts of Shanghai are sinking at a rate of about 10 millimeters a year. Most of it is caused by the pumping out groundwater. This could undermine Shanghai's foundations. The government is making an effort to rectify the situation. In the 1990s several billion dollars was authorized for a "green belt" and improved water and sewer facilities.

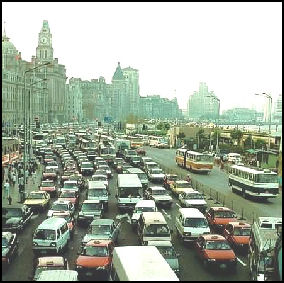

In 1995, there were 3.5 million bicycles and 350,000 cars in Shanghai. At that time traffic often grinded to a halt with bicycle gridlock when too many bicycles from different directions converged on a single spot. Over the past decade or so bicycles have given way to cars as hard as the Shanghai government has tried to prevent that from happening.

In the 1980s, planners in charge of overhauling and modernizing Shanghai made a great effort to spare the city traffic jams and pollution by constructed bridges, elevated highways and a new subway system. The government has also tried to keep cars off the road by making it expensive to own a car and difficult to get licence plates and drivers licenses. (See Education...Transportation, Transportation, Driving and Owning a Car in China). By some measures this has been a great success (Shanghai adds about one forth the number of new cars each year as Beijing, which has much lower licensing fees).

But still the effort has fallen way short of the goals that planners hoped to reach. Shanghai has become choked with cars, fumes, traffic jams and gridlock just like any other city. The planners planned for Shanghai to reach the 2 million vehicle mark in 2020. It reached that figure in 2005 and growth continues at a rate of about 15 percent a year. Another miscalculation has been the subway system. Some lines have fewer than expected riders. One of the problems is that not enough train cars are available and the trains are overcrowded, encouraging more people to use their cars.

Even if trains are available planners have to overcome an increasingly cavalier American attitude about driving. One Buick owner, who has station for a new train line near his home, told the New York Times, “I’m hoping other people will ride it so that the traffic gets better. I’ll keep driving my car, though. It’s more comfortable because I can listen to music, use the air conditioner, and its not crowded.” He added that fixing Shanghai’s traffic problem was the government’s problem. To relieve congestion an effort is being made to reserve some roads for cars and others for bicycles. So far the trend favors cars. In 2004, bicycles were banned from all major roads in Shanghai to make more room for cars.

Shanghai Expo 2010

The Shanghai Expo 2010 will be held in Shanghai over six months in 2010 and is expected to draw 70 million visitors and 200 participating nations. Far and away the most expensive World Expo ever, it will be held on a site that covers an area twice the size of Monaco. Billions of dollars will be spent on it and and tens of thousands of people will put to work. Clocks were have been placed throughout Shanghai to count down the days, hours, minutes and seconds until the event begins. Yao Ming and Jackie Chan have been selected as goodwill ambassadors. The pianist Lang Lang was selected to help promote the event and a big deal has been made about Denmark sending Copenhagen’s Little Mermaid to the event, comparing the move with sending the Statue of Liberty there. Website: en.expo2010 . See AMUSEMENTS IN NEW SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com

Romanian Pavilion

Image Sources: 1) CNTO (China National Tourist Organization; 2) Nolls China Web site; 3) Perrochon photo site; 4) Beifan.com; 5) developers, architecture firms, tourist and government offices linked with the place shown; 6) Mongabey.com; 7) University of Washington, Purdue University, Ohio State University; 8) UNESCO; 9) Wikipedia

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), UNESCO, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in May 2020