ROAD TRAVEL IN CHINA

Gas-powered bus

In 2003, an estimated 6,789,000 passenger automobiles used the highway system in China, up from 50,000 in 1949. In addition, there were some 17,222,000 commercial vehicles operating in the same year. In the early 1990s there were about 7 million motor vehicles, two-thirds of which were trucks and buses. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The highway and road systems carried nearly 11.6 billion tons of freight and 769.6 trillion passenger/kilometers in 2003. The importance of highways and motor vehicles, which carry 13.5 percent of cargo and 49.1 percent of passengers, was growing rapidly in the mid-2000s. Road usage has increased significantly, as automobiles, including privately owned vehicles, rapidly replace bicycles as the popular vehicle of choice in China. In 2002, excluding military and probably internal security vehicles, there were 12 million passenger cars and buses in operation and 8.1 million other vehicles. In 2003 China reported that 23.8 million vehicles were used for business purposes, including 14.8 million passenger vehicles and 8.5 million trucks. The latest statistics from the Beijing Municipal Statistics Bureau show that Beijing had nearly 1.3 million privately owned cars at the end of 2004 or 11 for each 100 Beijing residents. Beijing currently has the highest annual rate of private car growth. [Source: Library of Congress, 2008]

Rural roads are often in poor condition. Some roads have pavement sections that run only a few miles and then deteriorate into potholes, washboard ripples, dirt and rocks. Maps are often unreliable. Distances can be deceptive. Even on paved roads traffic is often slowed by potholes and slow trucks. A journey of a 100 miles through the mountains sometimes takes four or five hours. In villages, it is often impossible to drive. Villages were mostly built before people had cars. Homes are linked by foot paths.

Many highways are dominated by fully loaded trucks that have to brake hard when they go downhill. Car travel is still lighter than might be expected because Chinese are still not big on the idea of taking long car trips and tolls are high. Tractors sometimes use the main highways. Farmers sometimes put grain down on secondary roads to dry or to be threshed by passing vehicles.

Shanghai is better organized than Beijing transportation-wise. It has a larger population than Beijing but just one-third of the number of cars. (Shanghai has imposed limits since the 1980s on the number of autos that can be registered in the city and sells license plates through an auction system.) The transit system in Shanghai is better designed than the one in Beijing.

See Separate Articles: TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; AUTOMOBILES IN CHINA: GROWTH, POPULAR CARS, NUMBERS factsanddetails.com ; DRIVING IN CHINA: CUSTOMS, TESTS AND BAD HABITS factsanddetails.com ; ROAD TRAVEL, TRUCKS AND BUSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ROAD CONGESTION AND TRAFFIC JAMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRAFFIC ACCIDENTS, DRUNK DRIVING AND CAR, BUS AND TRUCK CRASHES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Country Driving: A Journey Through China from Farm to Factory by Peter Hessler, Peter Berkrot, et al. Amazon.com; Driving toward Modernity: Cars and the Lives of the Middle Class in Contemporary China by Jun Zhang Amazon.com; “English-Chinese and Chinese-English Glossary of Transportation Terms: Highways and Railroads” by Rongfang (Rachel) Liu and Eva Lerner-Lam Amazon.com ; “Decoding China's Car Industry: 40 Years” by Anding Li (2021) Amazon.com; Lonely Planet China" 16 Amazon.com

Road Travel in China in the 1980s

Old-style Chinese-made truck

In 1985 the transportation system handled 2.7 billion tons of goods. Of this, highways handled 762 million tons. The 1985 volume of passenger traffic was 428 billion passenger-kilometers. Of this, road traffic, for 157.3 billion passenger-kilometers. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

China's highways carried 660 million tons of freight and 410 million passengers in 1985. In 1984 the authorities began assigning medium-distance traffic (certain goods and sundries traveling less than 100 kilometers and passengers less than 200 kilometers) to highways to relieve the pressure on railroads. Almost 800 national highways were used for transporting cargo. Joint provincial-level transportation centers were designated to take care of crosscountry cargo transportation between provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities. A total of about 15,000 scheduled rural buses carried 4.3 million passengers daily, and more than 2,300 national bus services handled a daily average of 450,000 passengers. The number of trucks and buses operated by individuals, collectives, and families reached 130,000 in 1984, about half the number of state-owned vehicles. In 1986 there were 290,000 private motor vehicles in China, 95 percent of which were trucks. Most trucks had a four- to five-ton capacity.*

Although cars and trucks were the primary means of highway transportation, in the mid-1980s carts pulled by horses, mules, donkeys, cows, oxen, and camels still were common in rural areas. Motor vehicles often were unable to reach efficient travel speeds near towns and cities in rural areas because of the large number of slow-moving tractors, bicycles, hand- and animal-drawn carts, and pedestrians. Strict adherence to relatively low speed limits in some areas also kept travel speeds at inefficient levels.*

Buses in China

China is home to 700,000 buses and more bus manufacturers than any other country. Of the 90 or so companies, only 20 make more than 1,000 buses. Competition is very fierce. Some companies have succeeded by stealing designs of other companies and using gangster tactic to get their clients to buy their buses.

The buses in Zigong have huge five-foot-high bags on their roofs which run the length and width of the bus. The 1000-cubic- foot bags contain enough natural gas — which costs half as much as gasoline — to propel the bus for 50 miles. Potential riders know when the bag hangs limply from the roof they should think about taking a different bus. Beijing introduced 5,000 environmentally-friendly, natural-gas-powered buses to run at the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

Bus Travel in China

The Lonely Planet guide for China described one incident witnessed by a German traveler journeying between Wuzhou and Yangshuo involving two competing buses. "After getting up perilously close to its rear bumper and blasting furiously with an armory of horns, the driver managed, in a hair-raising exhibition of reckless abandon and daredevilry, to sweep around the opposite lane on a blind bend and be the first to get a group of passengers."

“The other driver, determined not to let this fellow get away with such deviously unsporting behavior, pulled up and started thumping him through the window. A decisive knockout proving elusive in such cramped quarters, the two soon leapt out of their buses to continue the punch-up on the roadside." The police soon arrived and without consulting the passengers handcuffed the drivers and took them away. "It was five hours before new drivers were dispatched to the scene of the crime."

Another Lonely Planet bus traveler reported sharing a bus with a Chinese girl with motion sickness. "The driver kept flying along, turned the internal loudspeaker on and blasted the girl: 'Hey you behind! get your head in! Get it in! Observe safety! Observes safety. While his voice rose to a frenzy, he turned in his seat to look back and the bus swayed violently."

One group of tourists on a broken down bus had to form a human chain across a road to get a vehicle to stop and help them.

Fake Bus Service in Shenzhen Results in Mass Mugging

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times: They have fake Louis Vuitton handbags, Rolex watches, Rolls-Royce cars and even entire Ikea stores. Now the counterfeiters of Shenzhen have outdone themselves by running a fake city bus service. The scam, intended to exploit the very lowest rung of urban Chinese commuters, combined the drudgery of a late-night journey on public transport with the misery of a backstreet mugging. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, March 9, 2012]

“Passengers unfortunate enough to be waiting at the bus stop on an evening when the fake No 868 drew up imagined they were boarding the real thing on a heavily used route between the Fuyong and Pingshan districts of one of the largest cities in the world. Passengers bought their tickets as normal, but once the bus was in motion they were confronted by four burly "conductors" who demanded everything they had in their bags and wallets. Any resistance was met with a beating. In some instances, the fake bus diverted from its regular route, with the thugs manhandling the passengers out on to the pavement and abandoning them in a different part of the city.

“The scam appears to have been the brainchild of a disgruntled former employee named only as Mr Xu. He was a driver on the No 868 route before being forced into retirement. In 2011, after nurturing his criminal plot for some months in his home town in Hubei province, Mr Xu assembled two business partners - identified by police as Mr Guo and Mr Gong - and invested 40,000 yuan ($5950) in a decommissioned bus he found in a Dongguan scrapyard. A further 10,000 yuan was spent on a paint touch-up and fake No 868 plates.

“However, his elaborate ruse had two important flaws: all of the victims were by definition poor, which meant that the average amount taken from each of them was no more than $10; while, because the gang was operating late at night, there were never more than a dozen people to rob at any one time. The gang was caught in March 2012 week after police boarded a suspect bus and, according to a local newspaper account, noticed that four "large men" on board suddenly became rather nervous. Unable to bear the tension, the quartet took thousands of yuan from their pockets and invited the officers to tea - an offer that was declined in favour of four immediate arrests.

Trucks in China

There are more than 1 million trucking and removal companies is China. The industry is hampered by provincial laws that often require advance approval to cross between provinces. Sometimes trucks have to endure customs checks and even unload and reload their cargo from one truck to another, increasing transportation time and the risk of spoiling and theft--when crossing from one province to another.

Describing a ride on delivery van making a 1,500 mile round trip between Beijing and Guangzhou, an MBA student told the Economist: "The trip took five and a three-quarter days. the truck was idle half the time. The average speed was 21 miles an hour. Not only did the truck have to carry its own fuel, but also its own mechanic. She witnessed 40 crashes, 20 head-on collisions and many major injuries. Half the time the two lane highway was under construction."

Truckers say they regularly encounter pieces or furniture and sometimes even dead bodies on the highway. One Chinese trucker told the Wall Street Journal, the corpses "could be genuine hit-and-run victims, or props for some highway-robbery or extortion scheme." Truck hijacking is a serous problem in southern China.

The roads in northern China are filled with Liberation-brand trucks carrying freight south from Inner Mongolia. Wind sometimes blow the cargo to one side so the trucks almost listand look as if they might topple over.

Truck Strike in Shanghai

In April 2011, thousands of truck drivers in Shanghai staged a three day protest over rising fuel prices they say was crippling their businesses. Truck drivers blockaded part of the city's port — China's busiest — disrupting the flow of goods. The protests were one sign of rising public anger over surging inflation.

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, Truck drivers disrupted operations at Shanghai’s seaport. Hundreds of demonstrators gathered at a container-handling facility at the city’s Baoshan port, news reports stated, monitored by dozens of police officers.... Thousands of drivers staged a noisy protest at the huge Waigaoqiao port, smashing truck windows of drivers who had refused to join them, and officers arrested several drivers who tried to overturn a police car. The drivers were protesting low wages, increased fuel prices — the government recently raised diesel prices by five percent — and higher fees imposed by port operators. “The various fees they have to pay leave them no profit,” said Liu Cheng, a law professor and labor specialist at Shanghai Normal University. “This kind of conflict is hard to resolve because it’s the government that is collecting those fees.” [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, April 22, 2011]

Near one of Shanghai's main port areas, where the Yangtze River meets the sea, groups of truck drivers milled around Friday near a long line of trucks parked bumper to bumper and side by side. On man told Reuters they can't even afford to eat because the price of gasoline is now so high. China has raised fuel prices several times in the past year, blaming the rising cost of crude oil. This month gasoline and diesel prices hit a record high after the government raised them by as much as 5 percent. The drivers are also angered at new fees introduced by warehouse operators.

One man claimed the police have responded with violence — beating up many truckers. One of his friends was beaten and another arrested, he says. The man claims that some 20,000 truckers have gone on strike. It's a number that is hard to confirm. The likelier number of about 2,000 protesters is still a major event in China.

China’s state-controlled newspapers ignored the strike, and censors removed reports on the disturbance from Web sites. News of recent strikes in Shanghai leaked out through the Chinese equivalents of Twitter, known as Weibo and used by many urban Chinese. Word about the strikes initially appeared there, before being deleted by the authorities.

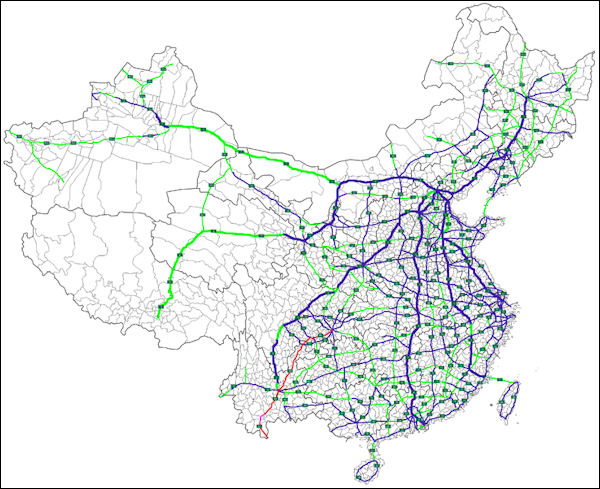

Map of China's NTHS Expressways

The strike eventually ended after government of Shanghai cut some fees. In 2008, China was hit with a wave of strikes by taxi and bus drivers unhappy with the erosion in their take-home pay. Also in April 2011, in what appeared to be a government bid to assuage some of the current economic unhappiness, Shanghai newspapers reported that the government would reduce the monthly fees that independent taxi drivers must pay the companies that employ them, to $1,260 from $1,305.

Image Sources: 1) University of Washington; 2, 9, 10) Beifan.com 3, 5 ) Nolls China website ; 4) Mongabey ; 6) CIA; 7) Gary Braasch; 8) Julie Chao; Wiki Commons; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022