ENERGY IN CHINA

China is the world's most populous country (with about 1.4 billion people) and is home to the world’s second largest economy after the U.S.. Its size and a fast-growing economy has led it to be the largest consumer and producer of energy in the world.. Despite structural changes to China’s economy during the past few years, and government policies support cleaner fuel use and energy efficiency measures, China’s energy demand is expected to increase, [Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020 ++]

China now accounts for about 24 percent of the world’s energy consumption, double what it was in the late 2000s when its rate of consumption was s growing more than four times the world’s rate. In 2009 China surpassed the United States to become the world’s top energy consumer according to the International Energy Agency, consuming 2,252 billion tons of oil equivalent energy from sources such as coal, nuclear power, natural gas and hydro-electric power — about 4 percent more than the United States. China has come a long way in a short period of time. In 2000, it consumed half the energy of the United States.

China needs energy to make its economy run. Just to keep pace with growth, China must construct approximately a dozen 1,000-megawatt power plants every year. By contrast the United States only needs one or two a year to maintain its growth rate.

Energy use (oil equivalent per capita): 2,224 kilograms (compared to 57 kilograms in East Timor and 6,804 kilograms in the United States). [Source: World Bank data.worldbank.org ]

See Separate Articles: ELECTRICITY IN CHINA: PRODUCTION, GRIDS, INEFFICIENCIES AND SHORTAGES factsanddetails.com; NUCLEAR POWER IN CHINA: EXPANSION, SAFETY AND POTENTIAL PROBLEMS factsanddetails.com; RENEWABLE ENERGY AND GREEN TECHNOLOGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; SOLAR ENERGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; WIND ENERGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; OIL IN CHINA: CONSUMPTION, PRODUCTION, HISTORY, GROWTH factsanddetails.com; NATURAL GAS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE OIL COMPANIES: PETROCHINA, SINOPEC AND CNOOC factsanddetails.com COAL IN CHINA: PRODUCTION, DAILY LIFE, SOURCES AND CUTTING BACK ON IT factsanddetails.com; U.S. Energy Information Administration Report on Energy in China eia.gov/international/analysis ; China Sustainable Energy Program efchina.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China’s Energy Security and Relations With Petrostates: Oil as an Idea” by Anna Kuteleva (2021) Amazon.com; “Energy Policy in China” by Chi-Jen Yang (2017) Amazon.com; “China’s Electricity Industry: Past, Present and Future” by Ma Xiaoying and Malcolm Abbott (2020) Amazon.com; “Globalisation, Transition and Development in China: The Case of the Coal Industry” by Rui Huaichuan (2004) Amazon.com; “China's Petroleum Industry In The International Context” by Fereidun Fesharaki (2019) Amazon.com; “China's Biggest Natural Gas Pipeline: Challenges and Achievements” (2008) by Liu Jing Amazon.com; “China, Oil and Global Politics” by Philip Andrews (2011) Amazon.com; “Oil in China: from Self-reliance to Internationalization” by Taiwei Lim (2009) Amazon.com

Energy Sources in China

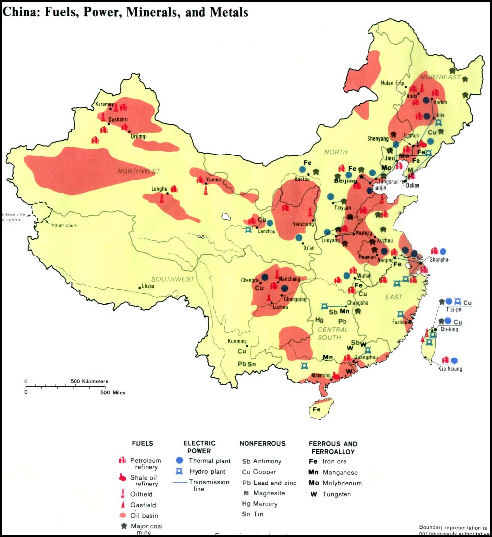

According to the World Bank China — with 20 percent of the world's population — possesses 2.34 percent of the world's oil reserves, 1.2 percent of the world's gas reserves, 11 percent of the world's coal and 13.2 percent of the potential hydroelectric resources. Energy production in 2005: 68 percent from coal, 23 percent from oil, 5 percent from hydro, 3 percent from natural gas and 1 percent from nuclear energy.

China is dependent on coal and oil. It is trying to diversify with natural gas, nuclear power and renewable sources but it will be long time before coal and oil are significantly displaced. Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times China has placed big bets on wind turbines for generating electricity. And despite Japan’s nuclear travails, China is also cautiously proceeding with plans to lead the world in the construction of nuclear power plants in the coming decade. But coal is still king in China. The country has nearly half of the world’s total coal-fired capacity, and coal plants currently represent 73 percent of this nation’s total generating capacity. Hydroelectric power, at 22 percent, is a distant second and has been hampered by droughts.”

Coal supplied most (about 58 percent) of China’s total energy consumption in 2019, down from 59 percent in 2018. The second-largest fuel source was petroleum and other liquids, accounting for 20 percent of the country’s total energy consumption in 2019. Although China has diversified its energy supplies and cleaner burning fuels have replaced some coal and oil use in recent years, hydroelectric sources (8 percent), natural gas (8 percent), nuclear power (2 percent), and other renewables (nearly 5 percent) accounted for relatively small but growing shares of China’s energy consumption. The Chinese government intends to cap coal use to less than 58 percent of total primary energy consumption by 2020 in an effort to curtail heavy air pollution that has affected certain areas of the country in recent years. According to China’s estimates, coal accounted for a little less than 58 percent in 2019, which places the government within its goal. Natural gas, nuclear power, and renewable energy consumption have increased during the past few years to offset the drop in coal use. [Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020]

Growth of Energy Use in China

China’s energy consumption has risen dramatically since the inception of its economic reform program in the late 1970s. Electric power generation—mostly by coal-burning plants—has been in particular demand; China’s electricity use in the 1990s increased by between 3 percent and 7 percent per year. In 2003 electricity use increased by 15 percent over the previous year, [Source: Library of Congress, August 2006]

China’s energy consumption has risen dramatically since the inception of its economic reform program in the late 1970s. Electric power generation—mostly by coal-burning plants—has been in particular demand; China’s electricity use in the 1990s increased by between 3 percent and 7 percent per year. In 2003 electricity use increased by 15 percent over the previous year, [Source: Library of Congress, August 2006]

Demand for energy is soaring as Chinese are buying more cars, moving into bigger houses that need more heat, purchasing more televisions, refrigerators and other appliances and starting new businesses and factories. Being the world's factory for many products also requires lots of energy. Some heavy industries still use outdated technology and waste and use too much fuel in the production process. In the early 2010s energy intensive industries (steel. aluminum, cement and chemicals) used a third of China’s total energy consumption. Construction accounted for 27 percent.

Energy consumption rose by 208 percent in China between 1970 and 1990, compared to 28 percent in most developed countries. and doubled again between 1990 and 2000 and again between 2000 and 2010. During the 2000s, every two years China built as many power plants as Britain did between the 18th and 21st centuries . The energy bureaucracy in China in 2000 had only 100 employees compared to 110,000 at the EPA and Department of Energy in the United States.

In 2002, China produced 934.2 million tons of oil equivalent and consumed 889.6 million tons. Per capita consumption was 687 kilograms, only a quarter of North Korea’s estimated consumption, a third of that in Hong Kong, and well below the average for Asia. In the mid 2000s, energy production failed to keep up with industrial demand, resulting in power cutoffs throughout most of the country. China used the energy equivalent of the burning of 2.7 billion tons of coal in 2006. In 2005 the Chinese Communist Party expressed the determination to reduce energy consumption by 20 percent per capita of the gross domestic product (GDP) by 2010. But the opposite happened. In the 2010s China consumed energy at a rate much higher than experts had originally predicted, with China using the amount of energy in 2010 that experts originally predicted for 2020.

Both China and India have been warned by the International Energy Agency that they need to do something to curb their use of energy or else they will cause a number of serious problem including increased production of global warming gases and strain the global oil trade, causing shortages and price hikes. In 2006 and 2007 China and India accounted for 70 percent for the increase in energy demand. By 2030 the two countries are expected to account for half of the world’s energy consumption.

Reasons for Increased Energy Usage in China

China’s ravenous appetite for fossil fuels is driven by China’s shifting economic base — away from light export industries like garment and shoe production and toward energy-intensive heavy industries like steel and cement manufacturing for cars and construction for the domestic market.[Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, May 6, 2010]

Almost all urban households in China now have a washing machine, a refrigerator and an air-conditioner, according to government statistics. Rural ownership of appliances is now soaring as well because of new government subsidies for their purchase since late 2008.

Car ownership is rising rapidly in the cities, while bicycle ownership is actually falling in rural areas as more families buy motorcycles and light trucks. A number of car companies in China have recorded record sales.

The increase in oil and coal-fired electricity consumption in the first quarter was twice as fast as economic growth of about 12 percent for that period, a sign that rising energy consumption is not just the result of a rebounding economy but also of changes in the mix of industrial activity. The shift in activity is partly because of China’s economic stimulus program, which has resulted in a surge in public works construction that requires a lot of steel and cement. Meanwhile, fuel-intensive heavy industry output rose 22 percent in the first quarter in China from a year earlier, while light industry increased 14 percent.

In the future, Zhou Xi’an, a National Energy Administration official, has said that fossil fuel consumption was likely to increase further because of rising car ownership, diesel use in the increasingly mechanized agricultural sector and extra jet fuel consumption for travelers. China’s recent embrace of renewable energy has done little so far to slow the rise in emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.

Energy, Industry and Economics in China

China has traditionally relied on energy-driven heavy industry to generate growth. Between 1980 and 2000 it relied more on light industry. These days it is producing lots cars, steel and things that other require lots energy to make. Some say this would not have occurred without government help.

China makes a lot of steel, aluminum, concrete and flat glass, all of which require lots of energy. Making matters worse is the fact that Chinese factories are not very energy efficient. On average China needs 20 percent more energy to produce steel than the international average, 45 percent more to make concrete. Makers of ethyl need 70 percent more energy. In the 2000s, the aluminum industry consumed as much energy as the entire commercial sector — all the hotels, restaurant, banks and shopping malls.

China’s official data reported that its economy grew by 6.1 percent in 2019, which was the lowest annual growth rate since 1990. After registering an average growth rate of 10 percent per year between 2000 and 2011, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth has slowed or remained flat each year since then. The 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and resulting economic effects has adversely affected industrial and economic activity and energy use within China. It pushed GDP growth to 2.24 percent in 2020, rebounding to 8 percent in 2021.[Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020]

China is transitioning away from an economy that relies on growth in the manufacturing and export sectors to one that is more service oriented. In 2018, the government attempted to reduce high local government debt levels, and cut air pollution levels from the industrial sector. China has been seeking ways to attract more private investment in the energy sector by streamlining the project approval processes, implementing policies to improve energy transmission infrastructure to link supply and demand centers, and relaxing some price controls.

Rapidly increasing energy demand has made China influential in world energy markets In the energy sector, the central government is moving toward more: 1) Market-based pricing schemes; 2) Energy efficiency and anti-pollution measures; 3) Competition among energy firms and greater market access for smaller, independent firms; and 4) Higher investments in more technically challenging upstream hydrocarbon areas such as shale gas and renewable energy projects.

The extraordinary growth in power generation in China slowed somewhat because of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009. Researchers at Stanford University who closely track China’s power sector, coal use, and carbon dioxide emissions in a rough projection estimated that China emitted somewhere between 1.9 and 2.6 billion tons less carbon dioxide from 2008 to 2010 than it would have under business as usual and the economic crisis didn’t happen. But after the crisis was over energy demand soared once again.[Source: Andrew C. Revkin, New York Times, January 6, 2009]

Chinese Government Energy Policy, Missed Targets and Dodgy Data

Beijing subsidizes, shapes and “guides” the energy market. The central government is trying to get local governments to stop building power plants and close down unsafe mines but these wishes are often ignored. Often it seems that the central government is too timid to enforce its orders or corruption culture is to embedded for anyone to anything about it. .The mining and energy industries are notorious for ignoring directives and rules set by the central government and following their agenda, with local government officials being more wrapped up with local concerns and enriching themselves than following national policies.

The shift in the composition of China’s economic output is overwhelming the effects of China’s rapid expansion of renewable energy and its existing energy conservation program, energy experts said. Already China has been unable to meet energy efficiency targets set in five-year plan, from 2006 to 2010, and seems unlikely to meet future targets — namely improving the energy efficiency by 40 to 45 percent by 2020. For a while, China seemed to be on track toward of of improving energy efficiency by 20 percent. goal. According to the ministry of industry and information technology, energy efficiency by more than 14 percent from 2005 to 2009 but it deteriorated by 3.2 percent in the first quarter of 2010. Without big policy changes, like raising fuel taxes, they can’t possibly make it, said Julie Beatty, principal energy economist at Wood Mackenzie, a big energy consulting firm based in Edinburgh, Scotland. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, May 6, 2010]

Complicating energy efficiency calculations is the fact that China’s National Bureau of Statistics has begun a comprehensive revision of all of the country’s energy statistics for the last 10 years, restating them with more of the details commonly available in other countries’ data. Western experts also expect the revision to show that China has been using even more energy and releasing even more greenhouse gases than previously thought. Revising the data now runs the risk that other countries will distrust the results and demand greater international monitoring of any future pledges by China. If the National Bureau of Statistics revises up the 2005 data more than recent data, for example, then China might appear to have met its target at the end of this year for a 20 percent improvement in energy efficiency. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, May 6, 2010]

Chinese Government and Energy Prices

Electricity, coal, fertilizer and water are all cheaper than their real cost. This is done to control the economy, avoid hardships for ordinary Chinese and as a consequence prevent social unrest. When oil prices rose to $160 and then dropped to $70 a barrel consumer prices in China remained largely unchanged. Even when prices reached $3.50 a gallon in the summer of 2008, many drivers received subsidies or compensation.

Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times in May 2011: “The government, for its part, has imposed an array of price controls, including on electricity rates, as it struggles to insulate the Chinese public from inflation. Consumer prices are rising 5.3 percent a year according to official figures, and Chinese and Western economists say the true rate may be nearly double that. But coal prices, which the government deregulated in 2008, are rising even faster in China, which is a net importer of coal despite having its own extensive mining operations.” [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, May 24, 2011]

“Huaneng, China’s biggest electric utility, said that electricity rates it charges customers should have been 13 percent higher in 2010 to match the increase in coal prices. But regulators held utility rates essentially flat. Spot coal prices in China have surged an additional 20 percent this year — to a record $125 a metric ton for top grades — partly because of floods in Australia’s and Indonesia’s coal fields and partly because Japan is buying more from the global market to offset its lower nuclear power output. But Chinese regulators have let electricity prices climb only 2.5 percent this spring. Residential users in China’s cities pay 8.2 cents a kilowatt-hour. That compares to a national average of 11 cents in the United States and 15 cents in the heavily urban mid-Atlantic region. Chinese industrial users in cities are supposed to pay 12 cents a kilowatt-hour, although politically connected businesses receive discounts; the average industrial rate in the United States is 7 cents, and 9 cents in the mid-Atlantic region.”

“Big power generators like Huaneng buy nearly half their coal on the spot market and the rest on long-term contracts with prices that rise more slowly. The government has put pressure on China’s coal mines, also largely state-owned, to continue supplying power companies with coal at below-market prices under long-term contracts. But the mines, which are also profit-oriented operations, have responded with their own form of passive resistance — by sending their cheapest, lowest-quality coal with the most polluting sulfur.” As a result, many power plants are now paying penalties to yet another arm of the government — environmental regulators — for burning the sulfur-spewing coal. That has further added to the utilities’ cost of doing business, said Howard Au, the chief executive of Petrocom Energy, a Hong Kong company that builds coal-blending facilities. Trying to help utilities reduce those environmentally and financially costly emissions, Petrocom has built a series of gray silos and red conveyor belts at Lianyungang port in northern China to dilute high-sulfur Chinese coal with low-sulfur imported coal.”

Energy in Rural Areas and China's Great Heating Divide

Coal briquettes Traditionally, coal has been the major primary-energy source, with additional fuels provided by brushwood, rice husks, dung, and other noncommercial materials. For some people coal, firewood or charcoal remain the main sources of energy. Coal briquettes like those pictured here have traditionally been used in many homes. The poorest people sometimes use dung and agriculture waste fires. People slightly better off use wood or charcoal and those better off still have access to propane and kerosene.

Some people suffer from respiratory illnesses caused by inhaling smoke from cooking and heating fires in huts with virtually no ventilation. Health experts estimate that 4 million children die worldwide from smoke-related respiratory. The illnesses are caused by inhaling carbon monoxide and particles of soot and ash — made with dung, agricultural waste and/or wood — everyday for years. Children's lungs are more sensitive than the lungs of adults. Coal and charcoal also cause a lot of air pollution.

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Growing up in Mao Zedong’s hometown of Shaoshan in southern China, Tan Huiyan remembers the wintertime sensation of stepping inside through her front door — and into the cold. “People in my hometown always say it’s colder in your home than outside in winter,” recalled Tan, 31, who now lives in Beijing. “When I came home, I had to change into warmer clothes. After taking off my winter jacket, I had to put on very thick and padded pajamas. My Nike sneakers were not warm enough to be used at home, I always had to change into boots with furs inside, like those Ugg boots.” Temperatures in Shaoshan can dip to as low as 23 degrees in January, and the average is around 46 degrees from December to February. But a dividing line — established by Communist Party officials almost 60 years ago — bisects China into wintertime central heating haves and have-nots, and Tan was on the wrong side of it. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, November 16, 2014]

“Every November 15, people who live in apartment complexes in Beijing, Harbin and hundreds of other cities north of the boundary will rejoice as government central heating plants are fired up, flooding warmth into homes for four months. Those who live south of the line will suffer the season with nary a puff of steam from a radiator.

“The heating divide, which traces the Huai River and Qin Mountains near the latitude 33 degrees north, dates from the 1950s. Back then, China started to install centralized systems for residential areas with assistance from the Soviet Union. Historically, many northern residents would have a kang, a brick bed heated by wood burned underneath it. But southerners had no such tradition. These days, with economic growth raising standards of living and private developers building homes and apartments, the Qin-Huai line is increasingly considered anachronistic, inconvenient and even inhumane. Some cities have experienced blackouts because so many people are plugging in space heaters.

“Pan Yiqun, a professor from the Institute of Heating, Ventilating and Air Conditioning and Gas Engineering at Tongji University in Shanghai, said using the Qin-Huai line “doesn’t suit people’s needs today.... Outdoor temperature should be the decisive factor on where heating should be provided.” Citywide systems like those in the north, she said, are inefficient because a lot of energy is lost moving hot water through pipes. Systems for each household or building are better.

“In Shanghai, where heating is not provided by the government, many new apartments have their own systems. But residents’ costs are significantly higher than in cities with government-provided heat. For a 1,076-square-foot apartment in Beijing, a resident pays about $490 for four months of heating. Shanghai residents using individual gas boilers or electric heaters pay almost double that for gas or electricity.

Inefficient Uses of Energy in China

China wastes a lot of energy. It uses four times more energy to each dollar of GNP than the United States and 12 times as much as Japan. Even India is twice as efficient as China when it comes to efficiently using energy. The Chinese energy system is full of inefficiencies. The government promotes industries such as aluminum, steel, cement, pulp, silicon, glass and chemicals that suck up huge amounts of energy. In 2004, China produced more aluminum than any other nation, and this accounted for almost 5 percent of all power used nationwide. Overall, industries accounted for over two thirds of China’s power consumption compared to just around a third in Britain.

The government controls energy prices and has kept them artificially low through subsidies. Subsidies keep the cost of gasoline and heating fuel low but encourages waste. Raising prices is very risky politically. At the same time, for a long time China did little to contain demand. Electricity rates have been kept down for years. Ping Xinqiao, a professor of economics at the University of Beijing, told the Washington Post, “The current price policy encourages people and companies to use electricity because electricity is so cheap.” There is no pressure of them to use energy resources efficiently. China has seemed willing to put up with energy inefficiency to hold off joblessness. But some policy decisions seem to be poorly made. Why, for example, are aluminum smelters kept open when they use the same amount of power as an auto factory that employ 100 times more people.

Chinese buildings are quite energy inefficient and Chinese homes tend to be thinly insulated. They require twice as much energy to heat and cool as American homes. A third of China’s carbon emissions and seven percent of the world’s emissions come from electricity and gas used by Chinese buildings. Each year for the past few years China has produced 75 billion square feet of commercial and residential space, more than the combined space of all the shopping ,malls and strip malls in the United States. All these space not only requires energy to build it also requires a lot of energy to heat and cool once it is occupied.

China faces severe energy resource shortages despite aggressive efforts to increase production at home and purchase more energy resources overseas. China had seen slowdowns in the growth in electricity supplies often because of shortages of coal or the ability to get the fuel where it was needed.

Energy Conservation in China

The 11th Five-Year Program, announced in 2005, called for greater energy conservation measures, including development of renewable energy sources and increased attention to environmental protection. Moving away from coal towards cleaner energy sources including oil, natural gas, renewable energy, and nuclear power was given a high priority. In a speech in March 2007 Chinese Premier Wen Jibao said that conserving energy was a top priority. China had tightened the energy efficiency requirements on new buildings and imposed fuel-efficiency standards on automobiles that are stricter than the ones in the United States.

Since then China has been working very aggressively to improve its energy efficiency. Columnist Thomas L. Friedman wrote in the New York Times: “China has already adopted the most aggressive energy efficiency program in the world. It is committed to reducing the energy intensity of its economy — energy used per dollar of goods produced — by 20 percent in five years. They are doing this by implementing fuel efficiency standards for cars that far exceed our own and by going after their top thousand industries with very aggressive efficiency targets. And they have the most aggressive renewable energy deployment in the world, for wind, solar and nuclear, and are already beating their targets.” [Source: Thomas L. Friedman New York Times, July 4, 2009]

The Chinese government is trying to shift towards a more sustainable model of development. It is experimenting with ecocities and introducing new green building codes. The government heavily subsidies wind and solar energy; imposes higher taxes on large cars than smaller ones. The U.S.-based Natural Resources Defense Council is working with Chinese businesses to audit energy consumption and develop a fund to bankroll the installation of more efficient equipment. The China Clean Energy Program estimates it could negate the need for 3,000 new power plans over the coming decades.

Energy Conservation Measures In China

Beijing has set up an “energy police” force whose job is to crack down on excessive lighting and heating and other wastes of energy in shopping malls and office buildings in the capital. The energy police will have the authority to fine violators. This is a step up from other energy efficiency programs that lacked concrete punishments. In the summer of 2007, several local governments banned the use of air conditioning except when it was excessively hot, over 33̊C, as part of the campaign to cut energy consumption and use energy more efficiently. In Beijing, the “energy police” were put work enforcing limits on air conditioner use and some government offices shut their air conditioning off in a show of solidarity for the campaign.

Improvements made by China in energy efficiency include 1) removing subsidies for motor fuel, which now costs more than it does in the United States; 2) enacting tough new fuel efficiency standards for new urban vehicles (36.7 miles per gallon); 3) setting high standards of energy efficiency for coal plants and buildings; 4) targeting the 1,000 top emitter of greenhouse gases to boost energy efficiency by 20 percent; and 5) shutting down many older inefficient boilers and power plants. If all the drivers in China would stop driving for a day it would save about 39.7 million gallons of gasoline. If all the drivers in the United States did the same it would save 385 million gallons of gasoline.”

An effort is being made to get homeowners, builders and developers to make dwellings more energy efficient. The multibillion dollar drive includes revoking the business licenses of developers that don’t comply with energy-saving laws and offering tax breaks and other incentives to homeowners to install low-energy lighting and better insulation. China has passed new regulations for making buildings more energy efficient but enforcing them is difficult. Only 10 building had applied for recognition in 2009 under a green-building rating system launched in 2007. Improvements on making buildings more energy efficient may be outweighed by the sheer number of buildings going up as a result of China’s real estate boom.

In November 2011, China imposed a nationwide tax on production of oil and other resources to raise money for poor areas and possibly ease public anger at the wealth of state energy and mining companies. The measure is aimed at generating revenue for poor areas that produce much of China's oil and other resources but receive little of the wealth. That imbalance has fueled ethnic tensions in Tibet and the northwestern Muslim region of Xinjiang. The tax applies to crude oil, natural gas, rare earths, salt and metals. Oil and gas were taxed at 5 to 10 percent of sales value while other resources were taxed at different levels. [Source: AP, October 10, 201]1

See Green Cities Under MEGACITIES, METROPOLIS CLUSTERS, MODEL GREEN CITIES AND GHOST CITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Economic Growth in China Thwarts Energy Efficiency Efforts

Industry by industry, energy demand in China is increasing so fast that the broader efficiency targets are becoming harder to hit. According to a New York Times article: “Although China has passed the United States in the average efficiency of its coal-fired power plants, demand for electricity is so voracious that China last year built new coal-fired plants with a total capacity greater than all existing power plants in New York State.” [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, July 4, 2010]

“While China has imposed lighting efficiency standards on new buildings and is drafting similar standards for household appliances, construction of apartment and office buildings proceeds at a frenzied pace. And rural sales of refrigerators, washing machines and other large household appliances more than doubled in the past year in response to government subsidies aimed at helping 700 million peasants afford modern amenities. Also as the economy becomes more reliant on domestic demand instead of exports, growth is shifting toward energy-hungry steel and cement production and away from light industries like toys and apparel.”

“Chinese cars get 40 percent better gas mileage on average than American cars because they tend to be much smaller and have weaker engines. And China is drafting regulations that would require cars within each size category to improve their mileage by 18 percent over the next five years. But China’s auto market soared 48 percent in 2009, surpassing the American market for the first time, and car sales are rising almost as rapidly again this year. One of the newest factors in China’s energy use has emerged beyond the planning purview of policy makers in Beijing, in the form of labor unrest at factories across the country.”

One management consultancy firm estimates that China will erect up to 50,000 new skyscrapers between 2010 and 2025. Along with smaller structures, McKinsey estimates that buildings will account for 25 percent of China's energy consumption by then, up from 17 percent today.

Saving Energy, See Automobiles,

Image Sources: BBC, Environmental News; Westport School; Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; The Stand, Environmental News; AP; China Daily and Environmental News

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2022