NUCLEAR POWER IN CHINA

Nuclear power generation plays a relatively small role in China’s total power generation portfolio. It supplies only around 1 or 2 percent of the country's energy needs. Still, China actively promotes nuclear power as a clean, efficient, and reliable source of electricity generation. China generated about 272 Terrawatt hours of net nuclear power in 2018, accounting for 4 percent of total net generation. However, the country rapidly expanded its nuclear capacity after 2015, which will likely boost nuclear-fired power production in the next several years. As of August 2020, China’s net installed nuclear capacity was nearly 46 gigawatts (GW), more than half of which was added since the beginning of 2015. Companies in China are constructing an additional 11 GW of capacity, about 18 percent of the global nuclear power capacity currently being built. These plants are slated to become operational by 2025, and several more facilities are in various stages of planning. [Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, September 30, 2020]

China is the world’s third largest consumer of nuclear energy after the United States and France. GlobalData Plc predicts it will pass France as the world’s No. 2 nuclear generator in 2022 and claim the top spot from the U.S. in 2026. Nuclear power contributed 4.9 percent of the total Chinese electricity production in 2019, with 348.1 TWh. As of June 2021, China had a total nuclear power generation capacity of 49.6 GW from 50 reactors, with additional 17.1 GW under construction. As of 2009 China’s civilian nuclear power industry had 11 operating reactors, producing about nine gigawatts of power when operating at full capacity, supplying about 2.7 percent of the country’s electricity. In 2007 the government set a goal of increasing that capacity more than fourfold by 2020. [Source: Wikipedia. Keith Bradsher New York Times, December 15, 2009]

To achieve these goals the Chinese government plans to spend $50 billion to build 100 nuclear reactors, each capable of producing 1 million kilowatts, at a rate of about four a year in the 2010a and 2020s. This is one of the most ambitious nuclear plant building drives on record. China is the only place in the world where nuclear power generation is regarded as a major growth industry. If all 100 plants are built it would be the world’s largest generator of nuclear power.

China has two rival state-owned nuclear power giants: the China National Nuclear Corporation, mainly in northeastern China, and the China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group, mainly in southeastern China. China plans move aggressively to build inland nuclear power plants. The plan kicked off in 2008 when work began on an $8.7 billion nuclear plant in eastern China in Jiangxi Province. Work on plants in Hubei and Hunan Provinces is expected to start soon.

There are no public discussions on the merits and risks of nuclear power. The government decides and that’s that. There are doubts as to whether or not China takes enough safety precautions. There are also worries that the increased number of plants will fuel international competition for uranium, causing prices to go up, and produce massive amounts of nuclear waste.

China produces 750 tons of uranium a year. Annual demand is expected to rise to 20,000 tons by 2020. In January 2011, China announced with great fanfare that it had developed the technology to reprocess spent nuclear fuel — something only a handful of countries can do and something that would help China deal with its lack of uranium deposits — then added a few days later that it would need at least a decade to develop the technology to do it on an industrial scale.

Electricity: from nuclear fuels: 2 percent of total installed capacity (2017 est.), 25th in the world. [Source: CIA World Factbook, 2022]

See Separate Articles: ENERGY IN CHINA: GROWTH, INEFFICIENCY AND CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com; ELECTRICITY IN CHINA: PRODUCTION, GRIDS, INEFFICIENCIES AND SHORTAGES factsanddetails.com; NUCLEAR POWER IN CHINA: EXPANSION, SAFETY AND POTENTIAL PROBLEMS factsanddetails.com; RENEWABLE ENERGY AND GREEN TECHNOLOGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; Articles on ENERGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; U.S. Energy Information Administration Report on Energy in China eia.gov/international/analysis ; China Sustainable Energy Program efchina.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Politics of Nuclear Energy in China” by X. Yi-chong Amazon.com; “Energy Policy in China” by Chi-Jen Yang (2017) Amazon.com; “China’s Electricity Industry: Past, Present and Future” by Ma Xiaoying and Malcolm Abbott (2020) Amazon.com; “China's Green Energy and Environmental Policies” by U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (2010) Amazon.com; “Energy, Environment and Transitional Green Growth in China” by Ruizhi Pang, Xuejie Bai, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Wind and Solar Energy Transition in China” by Marius Korsnes (2019) Amazon.com; “China's Wind and Solar Sectors: Trends in Deployment, Manufacturing, and Energy Policy” by Iacob Koch-Weser, Ethan Meick, et al. (2015) Amazon.com

Development of Nuclear Power in China

China’s nuclear development dates to 1955 when it concluded an atomic energy cooperation agreement with the Soviet Union. After that more energy was put into developing bombs than plants. However, in August 1972, reportedly by directive of Premier Zhou Enlai, China began developing a reactor for civilian energy needs. After Mao Zedong's death in 1976, support for the development of nuclear power increased significantly. Contracts were signed to import two French-built plants, but economic retrenchment and the Three Mile Island incident in the United States abruptly halted the nuclear program. Following three years of "investigation and demonstration," the leadership decided to proceed with nuclear power development. By 1990 China intended to commit between 60 to 70 percent of its nuclear industry to the civilian sector. By 2000 China planned to have a nuclear generating capacity of 10,000 megawatts, accounting for approximately 5 percent of the country's total generating capacity. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

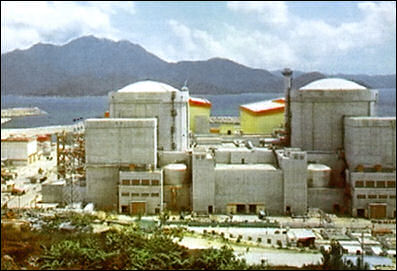

Construction of power-generating nuclear reactors began in the mid 1980s with the first ones, Daya Bay No. 1 and Qinshan No. 1 coming on line in 1994. The 279-megawatt domestically designed nuclear power plant Qinshan, Zhejiang Province was originally planned to be finished in 1989. Although most of the equipment in the plant was domestic, a number of key components were imported. The Seventh Five-Year Plan called for constructing two additional 600- megawatt reactors at Qinshan. The Daya Bay project, consisting of two 944 megawatt reactors at Daya Bay in Guangdong Province. was a joint venture with Hong Kong, with considerable foreign loans and expertise.*

In 1995, Chinese authorities approved the construction of four more reactors. In 2002 and 2003 two 1 GW units of the Lingao nuclear power plant came online. An additional 600 MW generating unit also came online at Qinshan in February 2002. Net capacity for China's three nuclear reactors was estimated at 2,167,000 kilowatts in 1996. At the start of 2002, installed capacity for nuclear power was placed at 2 GW. By mid-2005, that capacity had risen to 15 GW and further construction is being planned. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

As of 2006, China had 11 operating nuclear reactors, all of which were pressurized-water reactors (BWRs), and given approval for eight more. A 6 GW complex for Guangdong province opened at Yangjiang and a second facility opened at Daya Bay. As of 2011 China had seven nuclear power plants with 13 reactors. Twenty-six nuclear power plants with 53 additional reactors were planned or being built. Twelve of the 26 projects had been given the go ahead to be built. The 14 others had passed initial approval. China intended to have more than 100 reactors in operation by 2020.

After the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster in Japan in March 2011, China imposed a moratorium on the construction of new nuclear power plants. But that only lasted about a year and a half. Beijing approved four Hualong One reactors, the first to use the domestic technology, in 2019, ending a three-year freeze on new approvals caused by the government’s consideration of different technologies and the ongoing trade dispute with the U.S. Two more projects that will use Hualong One designs, with a combined cost of $10 billion, were approved in 2020.

Nuclear Power and Safety in China

Thus far there have been no major safety problems with Chinese nuclear reactors. Bradsher wrote: “Western experts regard the Daya Bay nuclear power plant in Shenzhen, which mainly uses French designs and is run by China Guangdong Nuclear, as evidence that China can run reactors safely. A display case holds trophies the power plant won in global safety competitions. The Daya Bay plant uses two loops of fluid in making power. The fluid in one heats as it circulates around the fuel rods, then transfers the heat to water in a second loop of intertwined pipes. The steam produced expands through a turbine, spinning it to generate electricity. [Source: Keith Bradsher New York Times, December 15, 2009]

“China National Nuclear likewise cooperates with international inspectors and has had no reported mishaps. But its roots are in a government ministry with close ties to the former Soviet Union, making it more of an enigma to most Western experts, and a corruption case involving its former president has added to their concern. China National Nuclear was on track to grow faster than China Guangdong over the next decade.” In October 2009, Prime Minister Wen Jiabao ordered a quintupling of the safety agency’s staff by the end of next year, to 1,000, according to United States regulators.

In May 2010, a Chinese nuclear plant experienced a small leak. A fuel rod at a state-owned nuclear power plant in southeastern China leaked traces of radioactive iodine into the surrounding cooling fluid, but no radiation escaped the building. The plant, located on Daya Bay in Shenzhen, adjacent to Hong Kong, continued producing electricity without disruption, the energy company CLP said. The Security Bureau of the Hong Kong government said that 10 radiation sensors in Hong Kong had not detected any increases since the leak. The leak occurred when radioactive iodine escaped from at least one of the French-made fuel rods, CLP said. The radioactive iodine, a byproduct of splitting uranium atoms, leaked into the fluid surrounding the fuel rods but did not contaminate the water whose steam powers the turbine, CLP said. A nuclear power plant built mainly to supply electricity to Hong Kong was shut down in 1995 when its control mechanism failed.[ Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, June 15, 2010]

Nuclear Power Expansion in China

In the 2010s China aimed to build three times as many nuclear power plants as the rest of the world combined, with construction starting on as many as 10 additional reactors a year. One reason for the expansion of nuclear power was to help slow the increase in greenhouse gas emissions. [Source: Keith Bradsher New York Times, December 15, 2009]

China wanted to increase in nuclear power electricity generating targets to 70 gigawatts of capacity by 2020 and 400 gigawatts by 2050, said Jiang Kejun, an energy policy director at the National Development and Reform Commission, the main planning agency. Electrical demand is growing so rapidly in China that even if the industry manages to meet the ambitious 2020 target, nuclear stations will still generate only 9.7 percent of the country’s power, by the government’s projections. Bringing so much nuclear power online over the next decade would reduce the country’s energy-related emissions of global warming gases by about 5 percent, compared with the emissions that would be produced by burning coal to generate the power.

Evan Osnos wrote on The New Yorker website in 2011 after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, “China is in the throes of building more new nuclear power plants than the rest of the world combined. It is adding twenty-four reactors and quadrupling its nuclear-power capacity in the coming decade to some forty gigawatts. The pace is so fast that the country’s nuclear safety chief publicly warned in 2009 that China would encounter safety and environmental hazards if it did not make a point of ensuring good construction. “At the current stage, if we are not fully aware of the sector’s over-rapid expansions, it will threaten construction quality and operation safety of nuclear power plants,” Li Ganjie, director of National Nuclear Safety Administration, told the International Ministerial Conference on Nuclear Energy in April 2009. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker , March 14, 2011]

“China presents a unique dilemma for energy strategists: it is expanding nuclear power in a race to meet rising demand for electricity and replace heavily polluting coal power plants. If China’s greenhouse emissions keep rising at the rate they have for the past thirty years, the country will emit more of those gases in the next thirty years than the United States has in its entire history. In some cases China builds world-class pieces of infrastructure, but we have also seen a steady drip of deeply disconcerting examples of a system growing too fast for its own good.

China has said that won’t let the nuclear crisis after the earthquake and tsunami in 2011 deter its nuclear power plant growth. After the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan the Chinese government suspended approvals for new projects pending safety reviews but said it planned to go ahead with previous expansion plans. Chinese Vice Minster of Environmental protection Zhang Lijium said, “Some lessons we learn from Japan will be considered in the making of China’s nuclear plants. But China will not change its determination and plans to develop nuclear power...We’re not going to stop eating for fear of choking.”

Problems and Dangers with China's Nuclear Power Expansion

The speed of the construction program and the plants themselves have has raised safety concerns both inside and outside China. Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times, “China is placing many of its nuclear plants near large cities, potentially exposing tens of millions of people to radiation in the event of an accident. In addition, China must maintain nuclear safeguards in a national business culture where quality and safety sometimes take a back seat to cost-cutting, profits and outright corruption — as shown by scandals in the food, pharmaceutical and toy industries and by the shoddy construction of schools that collapsed in the Sichuan Province earthquake last year.” [Source: Keith Bradsher New York Times, December 15, 2009]

At the current stage, if we are not fully aware of the sector’s over-rapid expansions, it will threaten construction quality and operation safety of nuclear power plants, Li Ganjie, the director of China’s National Nuclear Safety Administration, said in a speech. The challenge for the government and for nuclear companies as they increase construction is to keep an eye on a growing army of contractors and subcontractors who may be tempted to cut corners. It’s a concern, and that’s why we’re all working together because we hear about these things going on in other industries, said William P. Poirier, a vice president for Westinghouse Electric, which is building four nuclear reactors in China.

On the dangers of nuclear power in China, Brett M. Decker wrote in the Washington Times: China "is earthquake-prone and suffers regular damage from major tremors. Fault lines crisscross the mainland. This augurs poorly for Beijing’s nuclear blueprint. China National Nuclear, the country’s top nuclear-power developer, is planning to build a new nuclear plant in Chongqing, which is around 480 kilometers from the epicenter of a 7.9-magnitude earthquake in 2008 that left nearly 90,000 people dead or missing in neighboring Sichuan province.” [Source: Brett M. Decker, Washington Times, March 16, 2011]

“Another relevant - and frightening - factor is the Chinese institutional practice of cutting corners to try to get ahead. The power needs to sustain China’s huge population are putting pressure on the national energy grid, which in turn puts pressure on authorities to speed up their already mad sprint to build more nuke plants....It’s not as if “Made in China” is a brand that instills a lot of confidence either way. To put it gently, Chinese quality is years - if not decades - behind Japan, which is a global technological leader in many industries. If an unusually strong earthquake can lay waste to a first-world nation with strict building codes such as exist in the land of the rising sun, a record shock in backwards China would make last week’s devastation look like spring break in Fort Lauderdale.”

Nuclear Power, Corruption and Protests in China

In November 2011, Kang Rixin, the former head of China’s nuclear power program, was sentenced to life in prison on charges of corruption. The head of the most aggressive nuclear-power expansion in the world, he was convicted of taking $260 million in bribes, connected to rigged bids in the construction of nuclear power plants, and abusing his position to enrich others. Keith Bradsher wrote in New York Time, “While none of Mr. Kang’s decisions publicly documented would have created hazardous conditions at nuclear plants, the case is a worrisome sign that nuclear executives in China may not always put safety first in their decision-making.”

In July 2013, plans for a nuclear processing plant in southern China were scrapped following protest. AFP reported: Almost 1,000 people walked through the centre of Guangdong province's Jiangmen City, which is 30 kilometers (20 miles) away from the proposed facility at Longwan Industrial Park. The demonstration, which was billed as an innocent stroll, was organised online in opposition to the fuel processing plant, which some domestic reports say could have provided enough fuel for about half of China's atomic energy needs -- or 1,000 tonnes of uranium -- by 2020. The $6 billion project, which features uranium conversion and enrichment facilities, was cancelled on Saturday, state-run news agency Xinhua said, citing local officials. [Source: AFP, July 14, 2013]

Chinese Nuclear Safety After the Fukushima Crisis in Japan

In June 2011, AP reported: “China's nuclear regulators have given the country's reactors a clean bill of health following inspections ordered after the disaster at Japan's tsunami-struck Fukushima Dai-ichi facility. Inspections have been completed on all 13 of China's currently operating reactors in a process very similar to those in place in Europe and the United States, Vice Environment Minister Li Ganjie said in a statement posted on the ministry's website. Further safety reviews of 28 reactors now under construction should be completed by October, Li said. [Source: Associated Press, June 14, 2011]

“Li has called for a major overhaul of China's nuclear oversight in the wake of Japan's disaster, although there have been no signs that China plans to diverge from its ambitious program to develop the industry .China intends to have more than 100 reactors in operation by 2020, but has suspended issuing permits for new plants until a national nuclear safety plan is completed. China says the expansion is necessary to fuel an energy-hungry economy that is overwhelmingly dependent on coal.”

Andrew Kadak, a professor of nuclear science at M.I.T., who has worked closely with Chinese nuclear officials at the Daya Bay plant in Shenzhen, told The New Yorker . “I served on a safety oversight board at the Daya Bay plant, and we had free access to the facilities, including all levels of management. These are basically French-designed plants, and they were very well maintained. And our goal was to try to create a U.S.-type operating culture, and we tried to do that, and the Chinese were very receptive to that.” He went on, “The plants that are now being built have all the current state-of-the-art designs in them. The plants that failed [in Japan] were relatively old. That’s the good part. The unknown, of course, is how do you plan for a humongous earthquake and a humongous tidal wave, especially when they are situated in a place vulnerable to this kind of upset.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker , March 14, 2011]

When asked if Chinese plants are being designed to defend against the kinds of events that occurred in Japan, Kadak said, “Our safety reviews were more about day-to-day safety. We looked at their probabilistic risk analysis. They did not have access to seismic analyses. I’m assuming that the regulator would be doing that.”

China Bets on Small Reactors for a Piece of the Global Nuclear Market

In 2017, Reuters reported: “China is betting on new, small-scale nuclear reactor designs that could be used in isolated regions, on ships and even aircraft as part of an ambitious plan to wrest control of the global nuclear market. In the summer of 2017, state-owned China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) launched a small modular reactor (SMR) dubbed the "Nimble Dragon" with a pilot plant on the island province of Hainan, according to company officials. Unlike new large scale reactors that cost upward of $10 billion per unit and need large safety zones, SMRs create less toxic waste and can be built in a single factory. A little bigger than a bus and able to be transported by truck, SMRs could eventually cost less than a tenth the price of conventional reactors, developers predict. [Source: David Stanway, Reuters, Junw 14, 2017]

“Beijing is now racing the likes of Russia, Argentina and the United States to commercialize SMRs, which include passive cooling features to improve safety.“"Small-scale reactors are a new trend in the international development of nuclear power - they are safer and they can be used more flexibly," said Chen Hua, vice-president of the China Nuclear New Energy Corporation, a subsidiary of CNNC.

“Following the meltdown at Japan's Fukushima reactor complex in 2011, the beleaguered nuclear industry has been focused on rolling out safer, large-scale reactors in China and elsewhere. “But these so-called "third-generation" reactors have been mired in financing problems and building delays, deterring all but the most enthusiastically pro-nuclear nations. SMRs have capacity of less than 300 megawatts (MW) - enough to power around 200,000 homes - compared to at least 1 gigawatt (GW) for standard reactors.

“CNNC designed the Linglong, or "Nimble Dragon" to complement its larger Hualong or "China Dragon" reactor and has been in discussions with Pakistan, Iran, Britain, Indonesia, Mongolia, Brazil, Egypt and Canada as potential partners. "The big reactor is the Hualong One, the small reactor is the Linglong One - many countries intend to cooperate with CNNC's 'two dragons going out to sea'," Yu Peigen, vice-president of CNNC, said.

“CNNC is now working on offshore floating nuclear plants it plans to use on islands in the South China Sea, as well as mini-reactors capable of replacing coal-fired heating systems in northern China. Company scientists are even looking at designs that could be installed on aircraft. Elsewhere in China, Tsinghua University is building a version using a "pebblebed" of ceramic-coated fuel units that form the reactor core, improving efficiency. Shanghai scientists are also planning to build a pilot "molten salt" reactor, a potentially cheaper and safer technology where waste comes out in salt form.

“Officials acknowledge nuclear still struggles to compete with cheaper coal- or gas-fired power. The OECD Nuclear Energy Agency estimates developers will need to build at least five SMRs at a time to keep costs down. Taking into account much lower safety, environmental and processing costs, however, the agency said SMRs could be competitive with new, large-scale reactors - particularly in remote regions where the alternative is a costly extension of power grids "Given the delays and cost overruns associated with large-scale nuclear reactors around the world currently, the smaller size, reduced capital costs and shorter construction times associated with SMRs make them an attractive alternative," said Georgina Hayden, head of power and renewables at BMI Research.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2022