TEA IN CHINA

Tea is the most popular drink in China. Chinese love to drink tea and drink tremendous amounts of it. Prices range from few yuan per kilo for common teas to 6,000 yuan ($730) per kilo for the rarest varieties. Tea has traditionally been served as alternative to water in China. It is safer that tap water or river water because at least the water was boiled.

Tea is the most popular drink in China. Chinese love to drink tea and drink tremendous amounts of it. Prices range from few yuan per kilo for common teas to 6,000 yuan ($730) per kilo for the rarest varieties. Tea has traditionally been served as alternative to water in China. It is safer that tap water or river water because at least the water was boiled.

Chinese tea is relatively high in caffeine. Among the popular teas in southern China are jasmine “heung pin”, slightly bitter “sau mei”, earthy black “bo lei” and chrysanthemum tea. Many people recommend the “pu-er”, oolong and green teas. Shanghai gok fa cha ice tea is served with sugar. Hot tea is usually served plain, or with sugar or milk. Chinese tea often has a lot of stuff floating in it. Jasmine tea one Washington Post reporter commented “has so much foliage on the bottom that it resembles a terrarium.”

Annual tea consumption per capita: .57 kilograms (compared to 3.2 kilograms in Turkey; .23 kilograms in the United States and 0.014 kilograms in Mexico) [Source: Wikipedia Wikipedia ]

Tea is China's national beverage and the beverage offered at most meals, The most popular types of tea — green, black, and oolong — are commonly drunk plain, without milk or sugar added. Teacups have no handles or saucers. Han Chinese drink it unsweetened and black, Mongolians have it with milk, and Tibetans serve it with yak butter. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The famous Tang poet Lu Tong (775-835) wrote: “I care not a jot for immortal life, but only for the taste of tea.” Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: Tea has played a vital role in China throughout recorded history. It is an industry which generates jobs, has distinguished scholars, has been used as currency and cash, and is an important component of any meal or meeting. Through its gentle fragrant steam, many important decisions have been made in China; whether between Mao and Nixon or husband and wife, a cup of tea is always within reach. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

See Separate Article TEA: ITS HISTORY, HEALTH AND DIFFERENT KINDS OF TEA factsanddetails.com ; TEA CULTIVATION AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ; KINDS OF CHINESE TEA factsanddetails.com ;TEA DRINKING AND CULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;TEA AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TEA IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com ALCOHOLIC DRINKS IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; WINE AND BEER Factsanddetails.com/China ; EATING AND DRINKING CUSTOMS IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; COFFEE AND SOFT DRINKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article on History of Tea in China Wikipedia ; Rare Teas holymtn.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “For All the Tea in China: How England Stole the World's Favorite Drink and Changed History” by Sarah Rose Amazon.com; “All the Tea in China” by Kit Chow and Ione Kramer Amazon.com ; “Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History” by James A. Benn Amazon.com; “The China Tea Book” by Luo Jialin Amazon.com; “Chinese Tea” by Yun Ling Amazon.com; “The Ancient Art of Tea: Wisdom From the Old Chinese Tea Masters” by Warren Peltier and John T. Kirby Ph.D. Amazon.com; “The Tea Enthusiast's Handbook: A Guide to Enjoying the World's Best Teas” by Mary Lou Heiss (Author), Robert J. Heiss Amazon.com; “Puer Tea: Ancient Caravans and Urban Chic” by Jinghong Zhang and K. Sivaramakrishnan Amazon.com; “Tea Horse Road: China's Ancient Trade Road to Tibet” by Selena Ahmed and Michael Freeman Amazon.com; “The Ancient Tea Horse Road” by Jeff Fuchs Amazon.com; “The Ancient Tea Horse Road: Travels With the Last of the Himalayan Muleteers” by Jeff Fuchs Amazon.com

Tea

Tea is the most popular drink in the world after water. A lot more people drink it than coffee, especially in China, India, Japan, Britain, Russia, Turkey and other countries in Asia, eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Tea is a drink made with the leaves of “Camelia sinensis”, a plant indigenous to China. The word "tea" comes from the Xiamen area of China. Tea is one of the first known stimulants. The legendary Chinese emperor Shen Nung reportedly wrote in his medical diary in 2737 B.C. that tea not only "quenches thirst" but also "lessens the desire to sleep." According to legend Shen-Nung discovered the drink when some tea leaves from a bush accidently fell into some water he was boiling to stay healthy. He liked the taste and tea was born.

According to another legend tea was created by an Indian monk with bushy eyebrows named Bodhidharma, who mediated for nine years by staring at the wall of a cave. To battle his occasional bouts of drowsiness, he came up with a novel idea — cutting off his eyelids so his eyes wouldn't close. On the place where he placed his severed eyelids, the first tea bushes appeared.

Tea contains caffeine but significantly less than coffee. A typical cup of tea-bag-brewed tea contains 40 millimeters of caffeine, compared to 100 millimeters for a typical cup of brewed coffee. The caffeine content of tea can range from 20 to 90 milligrams per cup depending on the blend of tea leaves, method of preparation and length of brewing time. Contrary to myth, green tea contains about the same amount of caffeine as black teas.

See Separate Article TEA: ITS HISTORY, HEALTH AND DIFFERENT KINDS OF TEA factsanddetails.com

History of Tea in China

Camellia sinensis was already in use as a medicinal plant in the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 B.C.). The first recorded tea drinkers were the Ba-Shu of China's Sichuan province. By the time the "Chajing", the first book on tea, was written in A.D. 780, tea was widely cultivated in southwestern China and had been elevated to an.elixir of immortality. in Daoism, used as imperial tribute, savored by literati, transported on camelback to the Central Asian steppes and and sold on street corners. The aesthetics of tea culture flourished, evidenced in poetry, paintings of tea scenes, and especially in the Chinese mastery of producing ceramic tea wares. [Source: “Steeped in History: The Art of Tea” exhibition, Fowler Museum at UCLA, August 16-November 29, 2009]

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “The earliest authentic reference to tea drinking in Chinese literature is one that occurs in the biography of a well-known Chinese historian. It can be dated between the years A.D. 264 and 273. This historian had the misfortune to hold office under an emperor notorious for his drunken sprees. In the early part of this emperor's reign, so the biography tells us, the historian enjoyed the favor of the new ruler. Frequently he was invited to attend drunken feasts at which each guest was expected to drink no less than seven Chinese pints of wine. Our poor historian, alas, suffered bad health, which made it hard for him to keep up with his merry companions on these occasions. His own drinking capacity, the biography adds, was only three pints. [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

“In earliest times the Chinese seem to have used tea only as a tonic or medicine. For some time it was regarded by many of them with the suspicion people anywhere usually have for any unfamiliar food or product. Thus a Chinese book dealing with marvels and wonders of all kinds, and written within twenty years following the incident of the unfortunate historian, lists tea under a special section devoted to "Foods to be Avoided." It sternly warns the reader that "the drinking of true tea will cause people to suffer lack of sleep!"

Tea drinking became a symbol of upper-class refinement during the Tang dynasty (619-907). During the Tang period tea was compressed into bricks and then shaved and boiled in a cauldron, often along with other ingredients. Tea became a mass-market commodity under the Southern Song who ruled from 1127 to 1279. Cakes of tea the size of wagon wheels were given as tribute to emperors. The Song era (960-1279) brought the development of grinders to make powdered tea, which was then formed into cakes or simply whisked with hot water in a tea bowl. The first teapots specifically designed for brewing loose-leaf tea were created in the 1500s. These were unglazed pots from Yixing, still coveted today by collectors worldwide. During the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1264-1368) the Mongols of the north introduced their custom of combining tea with milk; for them it was a hearty drink to add to their diet of meat and dairy, giving them strength against the severe northern cold.

Loose-leaf tea and teapots are what the first European traders encountered when they arrived in China in the sixteenth century. Unknown to European consumers, tea was at first imported in small quantities as a companion import to spices and silks. As tea drinking became more popular, teapots and other Chinese ceramics were found to make practical ballast for sailing ships — stowed at ship‘s bottom to help stabilize the sailing. After the voyage these items were sold at a profit. Soon the demand for tea and.chinaware. increased as part of the chinoiserie phenomenon, the passion for all things Chinese that spread across Europe in the seventeenth century. China remained the sole provider of tea in world trade throughout the eighteenth century

World’s Oldest Tea — 2,150 Years Old — Found in Xian Emperor’s Tomb

In January 2016, archaeologists announced they had discovered the oldest tea in the world (2,150 years old) among the treasures buried with a Chinese emperor in Xian and in a tomb in Tibet. Archaeology magazine reported: The finds contain traces of caffeine and theanine — substances particularly characteristic of tea. The tombs are more than 2,000 years old, indicating the beverage was consumed during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220). A Chinese document from 59 B.C. that mentions a drink that might be tea was previously the earliest known record of the beverage. Tea does not grow near the tombs, so the discovery indicates that the Silk Road was a “much more complicated and complex long-distance trade network than was known from written sources,” says researcher Dorian Fuller, an archaeobotany professor at University College London. Tea-producing regions, including remote areas of China and even Myanmar, he adds, had “well established supply lines” feeding into the Silk Road. [Source: Lara Farrar, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

David Keys wrote in The Independent, “New scientific evidence suggests that ancient Chinese liked tea so much that they insisted on being buried with it – so they could enjoy a cup of char in the next world. The new discovery was made by researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and published in Nature’s online open access journal Scientific Reports. “Previously, no tea of that antiquity had ever been found – although a single ancient Chinese text from a hundred years later claimed that China was by then exporting tea leaves to Tibet. By examining tiny crystals trapped between hairs on the surface of the leaves and by using mass spectrometry, they were able to work out that the leaves, buried with a mid second century B.C. Chinese emperor, were actually tea. The scientific analysis of the food and other offerings in the Emperor’s tomb complex have also revealed that, as well as tea, he was determined to take millet, rice and chenopod with him to the next life. [Source: David Keys, The Independent, January 10, 2016 -]

“The tea aficionado ruler – the Han Dynasty Emperor Jing Di – died in 141 B.C., so the tea dates from around that year. Buried in a wooden box, it was among a huge number of items interred in a series of pits around the Emperor’s tomb complex for his use in the next world. Other items included weapons, pottery figurines, an ‘army’ of ceramic animals and several real full size chariots complete with their horses. -

See Separate Article FOOD, DRINKS AND CANNABIS IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com

Tea Traditions in China

According to the Fowler Museum at UCLA: Among Daoists, tea was thought to possess miraculous properties that promoted health and longevity. It was in fact viewed as the portal to enlightenment and the fabled herb of everlasting life. The impressive preventative and curative powers of tea also led to its prescription by apothecaries and physicians as tonic and remedy. Royalty and the aristocracy, ever in pursuit of health and long life, sought out Daoist healers for their palace courts. Recommending tea as a medicinal herb, beverage, and food, physicians worked closely with the master chefs of noble households. [Source: “Steeped in History: The Art of Tea” exhibition, Fowler Museum at UCLA, August 16-November 29, 2009]

According to the Fowler Museum at UCLA: Among Daoists, tea was thought to possess miraculous properties that promoted health and longevity. It was in fact viewed as the portal to enlightenment and the fabled herb of everlasting life. The impressive preventative and curative powers of tea also led to its prescription by apothecaries and physicians as tonic and remedy. Royalty and the aristocracy, ever in pursuit of health and long life, sought out Daoist healers for their palace courts. Recommending tea as a medicinal herb, beverage, and food, physicians worked closely with the master chefs of noble households. [Source: “Steeped in History: The Art of Tea” exhibition, Fowler Museum at UCLA, August 16-November 29, 2009]

Tea had ceremonial aspects at elegant court receptions and banquets …especially among conservative officials whose Confucian sensibilities dictated formality at every turn…but tea was not merely exchanged among the aristocracy at this time but was also sold in the market to commoners …tea had a role in the formal welcome and honor of visitors. The late Tang palace, the courts of the nobility and the wealthy held the art of tea in highest esteem, sparing no expense for fine tea or costly equipage. The emperor possessed the rarest teas. Ministers and civil officials, military officers, and functionaries were given monthly allotments, as tea was considered one of seven necessities of daily life: fuel, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce, vinegar, and tea.

The Uighur (nomadic people to the north) offered their herds, taking advantage of the Tang court to extort imperial princesses, silk, and fine tea. For nomads, tea was no mere luxury but an important supplement to their meat and dairy diet. Moreover, as an herbal medicine, it relieved many common ills.

Aromatic teas came in the shapes of squares, rounds, and flowers colored red, green, yellow, and black. The cake surfaces were elaborately decorated….The names of the teas were auspicious and ornamental, often suggesting preciousness and long life: Gold Coin, Jade Leaf of the Long Spring, Inch of Gold, Longevity Buds without Compare, Silver Leaf of Ten Thousand Springs, Jade Tablet of Longevity, and Dragon Buds of Ten Thousand Longevities….Each cake was set in a protective surround of fine bamboo, bronze, or silver and was wrapped in silk; broad, green bamboo leaves; and then more silk. Sealed in vermillion by officials, the tea was enclosed in a red-lacquered casket with a gilt lock and sent in fine, silk-lined, bamboo satchels by express to the emperor.

The milk-tea was ladled into bowls and drunk at each meal and throughout the day; the habit fostered the saying: “Three meals with tea a day lifts the spirit and purifies the heart, giving strength to one‘s labor. Three days without tea, confuses the body and exhausts the strength, making one loath to rise from bed..” Caked tea, however, did not readily die away. Among the aristocracy and conservative elite, the art of tea continued to revolve around it. The emperor‘s own son, Prince Ning, preserved the old forms of caked tea.

China-Tibet Tea Horse Road

For many centuries the Tea Horse Road was a thoroughfare of commerce and the main link between China and Tibet. Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic, “The ancient passageway once stretched almost 1,400 miles across the chest of Cathay, from Yaan, in the tea-growing region of Sichuan Province, to Lhasa, the almost 12,000-foot-high capital of Tibet. One of the highest, harshest trails in Asia, it marched up out of China's verdant valleys, traversed the wind-stripped, snow-scoured Tibetan Plateau, forded the freezing Yangtze, Mekong, and Salween Rivers, sliced into the mysterious Nyainqentanglha Mountains, ascended four deadly 17,000-foot passes, and finally dropped into the holy Tibetan city.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

Tea was first brought to Tibet, legend has it, when Tang dynasty Princess Wen Cheng married Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo in A.D. 641,” Tibetan royalty and nomads alike took to tea for good reasons. It was a hot beverage in a cold climate where the only other options were snowmelt, yak or goat milk, barley milk, or chang (barley beer). A cup of yak butter tea — with its distinctive salty, slightly oily, sharp taste — provided a mini-meal for herders warming themselves over yak dung fires in a windswept hinterland.”

Tea Carriers in 1908

“The tea that traveled to Tibet along the Tea Horse Road was the crudest form of the beverage. Tea is made from Camellia sinensis, a subtropical evergreen shrub. But while green tea is made from unoxidized buds and leaves, brick tea bound for Tibet, to this day, is made from the plant's large tough leaves, twigs, and stems. It is the most bitter and least smooth of all teas. After several cycles of steaming and drying, the tea is mixed with gluey rice water, pressed into molds, and dried. Bricks of black tea weigh from one to six pounds and are still sold throughout modern Tibet.”

By the 11th century, brick tea had become the coin of the realm. The Song dynasty used it to buy sturdy steeds from Tibet to take into battle against fierce nomadic tribes from the north, antecedents of Genghis Khan's hordes. It became the prime trading commodity between China and Tibet. For 130 pounds of brick tea, the Chinese would get a single horse. That was the rate set by the Sichuan Tea and Horse Agency, established in 1074. Porters carried tea from factories and plantations around Yaan up to Kangding, elevation 8,400 feet. There tea was sewn into waterproof yak-skin cases and loaded onto mule and yak trains for a three-month journey to Lhasa.”

“By the 13th century China was trading millions of pounds of tea for some 25,000 horses a year. But even all the king's horses couldn't save the Song dynasty, which fell to Genghis's grandson, Kublai Khan, in 1279. Nonetheless, bartering tea for horses continued through the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and into the middle of the Qing dynasty (1645-1912). When China's need for horses began to wane in the 18th century, tea was traded for other goods: hides from the high plains, wool, gold, and silver, and, most important, traditional Chinese medicinals that thrived only in Tibet. These are the commodities that the last of the tea porters, like Luo, Gan, and Li, carried back from Kangding after dropping off their loads of brick tea.”

“Just as China's imperial government used to regulate the tea trade in Sichuan, so monasteries influenced the trade in theocratic Tibet. The Tea Horse Road, known to Tibetans as the Gyalam, connected the important monasteries. Over the centuries, power struggles in Tibet and China changed the Gyalam's route. There were three main trunk lines: one from the south in Yunnan, home of Puer tea; one from the north; and one from the east cutting through the middle of Tibet. Because it was the shortest, this center route handled most of the tea.”

Tea Brings the British Empire and Opium to China

Frederic Wakeman Jr. Wrote in “The Fall of Imperial China” (1975): It was opium which bought the tea that serviced the E.I.C.’s [East India Company’s] debts and paid the duties of the British crown providing one-sixth of England’s national revenue. During the first decade of the nineteenth century…China’s balance of trade was so favorable that 26,000,000 silver dollars were imported into the empire. As opium consumption rose in the decade of the 1830s, 34,000,000 silver dollars were shipped out of the country to pay for the drug.

According to the Fowler Museum at UCLA: By the end of the eighteenth century, Britain‘s empire was comprised of eighty territorial units, eleven million square miles, and four hundred million subjects. Many arms of this empire served to provide the increasing quantities of tea needed to satisfy both the desires of British citizens and the revenue needed to fill the British coffers. At this time all tea imported to England was grown in China and the Chinese refused anything but cash (preferably silver bullion) as payment. In 1793 the Qianlong emperor wrote unequivocally to King George III:.I set no value on objects strange and ingenious, and have no use for your country‘s manufactures.. [Source: “Steeped in History: The Art of Tea” exhibition, Fowler Museum at UCLA, August 16-November 29, 2009]

The British realized that what was needed to improve their trade imbalance with China — incurred in part by paying cash for tea — was a commodity that they could use to generate profit. The solution they found — opium — would rip apart the seams of Chinese society, leading to untold suffering and political and financial ruin. Smuggled by the British from India where it was grown into China where it was becoming the source of increasing addiction, it provided the British with almost all of the money it needed to buy tea. Opium had first been brought to China in the eighth century by Arab traders. Much later, the introduction of the pipe by the Dutch in the sixteenth century expanded the Chinese use of opium, which was mixed with tobacco and smoked. The Dutch and the Portuguese eventually did quite handsomely with this trade, but the British operation, organized on a much grander scale, was particularly insidious in that Britain produced opium using — and frequently abusing — indentured labor in India and then sold the drug inside China. This trade prospered despite concerted efforts by the Chinese to stop the flow of the drug, efforts that were undermined by the complicity of Chinese smugglers. As opium consumption in China rose in the 1830s — with an estimated three million Chinese addicted — the balance of trade was reversed and silver flowed from China into the coffers of the East India Company.

The Chinese government finally took drastic measures, burned the drug and the ships that carried it, and jailed the British sailors in a major effort to stop the drug trafficking. These acts led to the declaration of war, usually known as the Opium War (1840‒1842), followed by a second Opium War (1856‒1860). The treaties ending the wars thoroughly weakened the Chinese government and gave Britain new strengths and territories in Asia.

In the 19th century the journey from China to London was made in sturdy ships owned by the East India Company. The ships, called the East Indiamen, received their cargo in the Chinese port of Canton, sailed around the Cape of Good Hope, along the western coast of Africa (stopping for food and supplies in St. Helena, an East India Company-owned base), to the Canary Islands where they loaded citrus fruits needed to prevent scurvy, and on to London. The trip could take more than six months, and much of the time pirates and privateers were real threats.

Tea Exports from China in 19th Century

Tea was also a major export item in the Qing Dynasty. According to Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware: Between 1840 ~and 1886 the production and trades of Chinese tea rose, the area for tea production was enlarged, and the amount of production increased. From statistical records, the total amount in production for the whole of China was around 50,000 tons and the total amount of tea exported was 19,000 tons in the 1840s. By 1886, the total amount of tea produced and exported reached 250,000 tons and 134,000 tons respectively — a 500 percent and 700 percent increase in four decades. At the time the total amount of tea exported accounted for 62 percent of all of China's exports. [Source: Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware +++]

The rise in tea trade was mainly due to the rapidly growing demand for tea by foreigners. The signing of the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 forced the Qing government to open five ports for trade, which, together with the advent of fast transport boats, increased the development of sea trade. But the rise in tea trade was also because China needed to balance its trade deficit. By around 1842, China was importing opium in vast amounts. In order to pay for the imports, the Qing government enlarged its export of silk and tea to bring money into China. These actions in turn increased tea selling. +++

Between 1887 and 1949, the Chinese tea trade declined. After the Dutch and the British began planting tea in their colonies (around 1886), China's leading position in tea trading was eroded and later replaced. During that time, places such as Indonesia, India, and Sri Lanka became major tea producers. This was partly because these new tea makers were using machines to make tea. They were more efficient and more competitive than China, not just in quantity but also in quality. China was still producing tea with old methods at the time. Gradually, the British and Americans took away the black tea market from China; Japan took away the green tea market. All these factors minimized Chinese tea's competitiveness in the world and squeezed China out of the world market. +++

Tea Exports from China in the 20th Century

“Apart from that, wars continuously loomed in China, including The War of Resistance against Japan and the Chinese Civil War. These slowed economic development in China. Tea gardens were deserted. In 1949, for example, the amount of tea produced was only around 41,000 tons, whereas for tea exported, 9,000 tons. It was not until after 1950 when Chinese tea selling resumed. [Source: Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware +++]

“Apart from that, wars continuously loomed in China, including The War of Resistance against Japan and the Chinese Civil War. These slowed economic development in China. Tea gardens were deserted. In 1949, for example, the amount of tea produced was only around 41,000 tons, whereas for tea exported, 9,000 tons. It was not until after 1950 when Chinese tea selling resumed. [Source: Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware +++]

After the new Chinese Government was established in 1949 and the political environment stablised, Chinese tea production recovered with the support of the new government. From 1950 to 1988, China (including Taiwan) expanded its tea plantation fivefold from 3,170,000 acreages to 16, 300,000 acreages. The amount of tea produced was increased from 75,000 tons to 569,000 tons — an increase of more than 7 times. The total amount of tea exported rose almost 8 times from 26,000 tons to 206,000 tons. China broke the record in the total amount of tea produced in 1976, with 258,000 tons; and in 1983 it broke the record in the total amount of tea exported with 137,000 tons.

As of the early 1990s China held around 45 percent of the total tea production area of the world and remains in a leading position. As for its share of the tea market, China has increased its share from 11.9 percent in 1950 to 23 percent in 1988. China has also increased its total tea export from 6.5 percent, of all of China's export, to 20 percent. These have been the result of a stable government and its staunch support for tea development.

Quality Tea in China

As tea culture developed in China over thousands of years, people began to appreciate the shape of the leaves as well as the taste. This aesthetic, which reduced the available supply, means only the best-looking leaves that can command the highest prices are gathered in some areas. [Source: Ben Yue, China Daily, March 28, 2011]

Spring is the crucial season for the tea business. Tea that matures then is of the highest quality thanks to low temperatures and dry conditions. Research by the China Tea Marketing Association (CTMA) shows that the trade in spring tea accounts for 75 percent of the entire year by value, although it consists of only 39 percent of the year's production by volume. According to Chen Jiatong, a tea retailer from Fujian province, the 2011 spring tea came on the market in mid-March, two weeks later than usual, because spring was much colder. The delayed picking time reduces production of spring tea but improves the quality, both of which lead to higher prices.

Special tea from Yunnan Province can sell for as much $75 for 100 grams at a tea shop in Tokyo that specializes in teas from China and Taiwan. Vintage tea leaves from 1987 at the same shop sell for $300 for 100 grams.

Chinese Investors Get Picky about Rare, Exotic Teas

Rare and exotic teas are fast developing into investment opportunities. Xinhua News Agency reported futures in the best quality Longjing (or Dragon Well) spring tea, the leaves of which will be picked before early April, have already sold out at 60,000 yuan ($9,146) a kilogram. The teas are mainly given as presents between businessmen after being packaged into a luxury product, according to Zhu Baichang, president of Hangzhou Longjing Tea Group. [Source: Ben Yue, China Daily, March 28, 2011]

The price of Longjing has boosted expectations for this year's spring tea market. Experts said the average price set by farmers might be up 15 percent because of high demand, unusual weather that has improved quality and soaring labor costs. For some specific brands, the retail price could increase more than 50 percent.

Tieguanyin tea In Beijing's Maliandao Tea Street, the biggest tea trade hub in southern Beijing, business is getting busier day-by-day. "We have to delay our closing time from 6 to 8 pm from this week (from March 21)," said Chen Jiatong, a tea retailer from Fujian province, from where most tea entrepreneurs come. "We have been selling about 100 presentation boxes a day recently. Each one contains 500 grams of Longjing tea. Those priced between 600 and 1,000 yuan a box sell the best," she added.

Another retailer, Baoxing Haixin Tea Ltd, which grows organic green tea in Sichuan province, predicts the price should be up about 20 to 30 percent. "Our tea hasn't been picked yet. My boss just called and said the bottom line for this year is 2,400 yuan a kilogram." He predicted a bright future for the tea business, partly because of the beverage's health associations.

"We think the future will be in high-level tea that can go the way of quality French wines in that consumers will care about the varieties and growing area, while lower-quality tea will be manufactured the same way Lipton's is," Wu Xiduan, general secretary of the China Tea Marketing Association (CTMA), told the People’s Daily. Although Wu said he doesn't believe the 60,000-yuan-a-kilogram tea will have an effect on the regular market, the public knows that only the best varieties growing in a few very limited sites will have any investment value. Just as in wine production, good tea-growing sites must have the most suitable temperature, sunshine and humidity for their specific, native varieties. Furthermore, production must be limited.

Chinese Tea Connoisseurs

Some say China's nouveau rich are harking back to ancient times as witnessed in literature depicting the rituals surrounding the drinking of tea by nobility. In A Dream of Red Mansions, Miaoyu, a beautiful nun, collects snow in plum blossoms and buries them underground in sealed jars for five years, creating an aromatic beverage that became a highly prized tea. [Source: Ben Yue, China Daily, March 28, 2011]

"About 10 percent of our customers bring their own tea to the tea house," said Zhu Jinwu, owner of Beijing Jianchashuiji Tea House. "Some of them have received expensive tea from their friends or business partners. They want to brew it professionally here, where the water and techniques are better. Sometimes they also want us to help them to appraise the tea's fair value," he added.

As the price of the best teas soars, wealthy tea-fanciers are considering conducting the quality-control themselves to hedge their risks. Mr Li, an artist from Beijing who was reluctant to reveal his full name, owns two tea shrubs at a friend's farm on the top of Huangshan Mountain, in Anhui province, where the rare green tea variety Huangshan Maofeng grows. He gives the teas as special presents to new business partners.

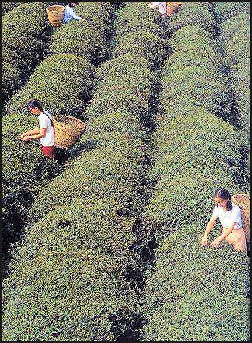

Tea Agriculture in China

China is the world’s leading tea producer. India is second. Sri Lanka and Kenya are large producers. China exports around $100 million worth of tea every year. A lot of the tea produced in China is consumed domestically. In 2009, tea is grown on 1.86 million hectares in China, the largest amount of any country in the world. China also produced the most tea that year, harvesting 1.35 million tons. [Source: Ben Yue, China Daily, March 28, 2011]

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: One of the most famous teas in China comes from the eastern city of Hangzhou, a place called Dragon Well that sits in the hills. If you visit Dragon Well, you can experience the making of tea firsthand. Farmers roam the steep hills terraced with tea bushes carefully picking delicate buds, placing them in a big woven basket. Once the basket is full of tea leaves, the farmer carries it down the mountain and begins the drying process. As you stroll through the small villages, you will see large heated shallow cone-shaped vats that the tea leaves are hand dried in to make tea. Rough hands swirl the leaves around and around the rim, releasing a musty fragrance as moisture is released from the leaves. It seals in the flavour which is released when moisture is added back as the tea leaves are seeped in hot water to make tea. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

See Separate Article TEA AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Tea Businesses in China

More than 80 million people work in the tea industry as farmers, workers or sales people. Chinese government is concerned that the tea industry was too diffuse. China has 70,000 tea companies but not a single internationally strong brand. There is a widely known saying: "Seventy-thousand Chinese tea companies are equal to one Lipton in terms of turnover." According to guidelines from the Ministry of Agriculture issued in 2009, China plans to focus tea production into four main areas and improve tea quality by employing better growing methods by 2015. [Source: Ben Yue, China Daily, March 28, 2011]

"The hundreds of different types of tea drunk by Chinese people mean it's not possible to develop the Chinese tea industry into a company like Lipton's, which is standardized with no difference in quality," said Wu Xiduan, general secretary of the China Tea Marketing Association (CTMA)

Exotic Tea Businesses in China

A modern Chinese tea company is contemplating delivering an equally powerful image to the world. Sichuan Emei-shan Zhuyeqing Tea Co Ltd, one of the nation's largest by sales, sells its flagship product "Spring Autumn of the Han Dynasty" at 23,800 yuan for a 500-gram presentation box. All the leaves are perfectly shaped. Even the box recalls the Han Dynasty (206 BC to AD 220) with its red and black paint.

The company now runs more than 100 boutique shops in China. There are 15 shops in Beijing. Some of them are next to high-end supermarkets such as BHG. People can sample the drink there and inspect the boxes. The "Lun Dao" series comes in a box designed by Chen You-jian, the famous Hong Kong art designer. They are sold for about 3,000 yuan each, and are considered to be collectors' items.

Another retailer, Baoxing Haixin Tea Ltd, grows organic green tea in Sichuan province. The owner of the business, Zhang Haixin, was a paper trader 20 years ago. In 1991 he bought a 20-hectare farm growing a local variety of green tea called Zhuyeqing (or Bamboo Leaf) organically. Every spring, the company invites skilled tea workers from Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, where the most famous green tea, Longjing, grows. As the organic lifestyle has become more popular, Zhang's business has grown rapidly.

Image Sources: Mostly Wiki Commons plus 1) Columbia University, University of Washington, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html, Julie Chao

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021