RESTAURANTS IN CHINA

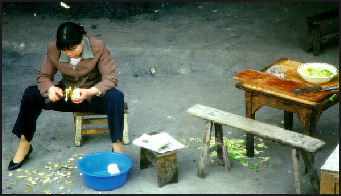

Street restaurant

China has many restaurants. One reason is that people have so little room in their homes and go out when they entertain and socialize. Another reason is that restaurants are small so there are a lot of them. In the towns and cities on the well-beaten tourist routes there a lot restaurants that cater to tourists. Where backpackers gather they often offer backpacker fare such as omelets, pancakes, sandwiches and muesli as well as Chinese food.

Some restaurants have over 400 items on the menu, including things like fried rice cakes with peanut butter sauce, crab with ginger and hoisin sauce, spicy Hunan squash, Sichuan pepper pork, lotus seed soup served in a melon shell, shark fin soup, bird nest soup, dragon-shrimp lobster, Chenchiang-style spiced pork, unicorn sea peach, and golden coin chicken pagodas with lotus-leaf bread. More mundane Chinese dishes include fried noodles, fried rice, fried rice with chicken, fried rice with pork, fried rice with prawns, stir fried vegetables, fresh boiled shrimp, crispy fried noodles, sweet and sour vegetables, beef in oyster sauce, chicken with ginger and coconut milk, fried rice with ginger, grilled fish, chicken or prawn soup, sweet and sour pork, sweet and sour chicken, and a choice of soups. Restaurants along the ocean are famous for fish, prawns and other kinds of seafood.

The first private restaurant in Beijing opened in 1980. By the late 2000s, there were over 20,000 dining establishments in the city. The “informal eating out” market in China, according to McDonald’s, was worth $300 billion a year at that time and was expanding at a rate of 10 percent a year. Leading restaurant chains at that time included Peking Quanjude, Tianjin Goubuli and Chongqing Cygnet. Local restaurants have names like “Buy Cheap Eat Happy.” Themed and foreign restaurants include Brazilian restaurants where the staff dress up like cowboys and swing around long carving knives used to slice up the 28 kinds of meat.

Before the Deng era, restaurants in China were often shabby, depressing places and foreign cuisine was hard to come by except at expensive hotels. These days Beijing is filled with outdoor cafes, jazz bars, pubs and restaurants, where foreigners and Chinese yuppies dine on mushroom-stuffed ravioli or salmon with caviar and dill. In the large cities there are food courts just like those in American shopping malls

Top chefs now can earn as much in Beijing and Shanghai as they can in New York City. Molecular cuisine — where machines using 170 degree C liquid nitrogen and other devises reshape, liquify and gasify foods into new forms — has found its way to China. Among the molecular cuisine dishes at the Shangri-La Beijing Blue Lobster restaurant are watermelon bisque served in test tubes, shark fin soup served in capsules, bird nest soup jam, and clear tomato soup with a beer-like foam.

See Separate Articles: FOOD IN CHINA: DIET, EATING HABITS AND TRENDS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE CUISINE factsanddetails.com ; MEAT IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HAIRY CRABS AND SEAFOOD IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; VEGETABLES AND FRUIT IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SNACKS, DESSERTS AND SWEETS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RICE, TOFU, DUMPLINGS AND NOODLES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; REGIONAL CHINESE CUISINES factsanddetails.com ; FAMOUS CHINESE FOODS AND DISHES WITH INTERESTING, FUNNY NAMES factsanddetails.com ; BIRD'S NEST SOUP factsanddetails.com RESTAURANTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAST FOOD AND FOOD DELIVERY BUSINESSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; EATING CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BANQUETS, PARTYING AND DRINKING CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Good Academic site on regional cuisines kas.ku.edu ; China.org Food Guide china.org ; Travel China Guide travelchinaguide.com ; China.org Rice Culture Article china.org ; Eating China Blog eatingchina.com/blog ; Imperial Food, Chinese Government site china.org.cn; Wikipedia article on History of Chinese Food Wikipedia ; Chopstix chopstix.com ; Asia Recipe asiarecipe.com ; Chinese Food Recipes chinesefood-recipes.com : Food Tours in China, China Highlights China Highlights Books: “Beyond the Great Wall; Recipes and Travels in the other China” by Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid (Artisan, 2008) features travel stories, political analysis and recipes from Tibet, Xinjiang, Guizhou, Inner Mongolia and other places off the beaten track in China.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants” by John Jung Amazon.com; “Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America” by Yong Chen Amazon.com; “Chinese Street Food: Small Bites, Classic Recipes, and Harrowing Tales Across the Middle Kingdom” Amazon.com; “Chinese Snacks: Wei-chuan Cook Book (1974) by Huang Su-Huei Amazon.com; Dim Sum and Other Chinese Street Foods by Mai Leung Amazon.com; “Dim Sum: Dumplings, parcels and other delectable Chinese snacks in 25 authentic recipes” by Terry Tan Amazon.com; “From Canton Restaurant to Panda Express: A History of Chinese Food in the United States” by Haiming Liu Amazon.com; “Ziangs Food Work Shop - Chin and Choo's Chinese Takeaway Cooking Bible: Cook how the Chinese Takeaways actually cook” by Chin Taylor and Choo Taylor Amazon.com

Where to Get Food in China

Good food can be found at expensive hotel restaurants, working class noodle houses, one-room family-owned restaurants, dumpling houses and sidewalk dumpling stalls.Robert Guang Tian and Camilla Hong Wang wrote in “Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies”: “Dining out is one of the most important social activities for both personal and business reasons in China. The food service can be categorized as fine dining, family restaurants, neighborhood restaurants, quick-serve restaurants, street vendors, food courts, and cafeterias operated by the institutions or corporations. Since the 1980s, Western-style chain restaurants have been the driving force for the development of service, quality, value and distribution in the Chinese food service industry." A survey in the early 2000s indicated that China had approximately "2.2 million restaurants and cafeterias. With the growth of China's economy, the changing life styles, and increased disposable incomes for the potentially largest group of middle-income families in the world, China is expected to be the new leader in the growth of the food service industry in the 21st century. [Source: Robert Guang Tian and Camilla Hong Wang, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies”, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

The large cities have restaurants serving Italian, French, Thai, Indian Japanese, Korean and other ethnic cuisines as well as American-style fast food restaurants such as McDonald's, Pizza Hut and Kentucky Fried Chicken. Off the beaten path the choice is usually more limited: mostly small local restaurants and noodle and dumpling shops. The most basic restaurants are often nothing more than a cook with a pot of soup and some benches and a table set up on the side of the street. Restaurants in the Communist were often seedy places that offered dumplings and noodles and little else.

You can also get food at markets and shops. Cities and some large towns have relatively well-stocked Western-style supermarkets, convenience stores and Mom-and-Pop corner stores where you can buy soft drinks, beer, chocolate, cup of noodles and snacks such as Chinese-style crackers and bean paste cakes. Some chain supermarkets stay open late. In rural areas the selection is more limited. Stores generally have cookies, packages of noodles and soup, potatoes, cabbage, rice, vegetables, powdered and condensed milk and hard candy. Fruits and vegetables are usually in ample supply in season. Many people grow food for themselves and shop at local markets, buying things like potatoes, cabbage, tomatoes, pumpkins. squash, dried fruit, nuts, vegetables, sausages, local honey, yoghurt, bread, and melons. Weekly markets are a good place sample street food and shop for fruit and vegetables.

Links in this Website: FOOD IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; MEAT, VEGETABLES, SWEETS AND FRUIT Factsanddetails.com/China ; RICE, TOFU, DUMPLINGS AND NOODLES Factsanddetails.com/China ; REGIONAL CHINESE FOOD Factsanddetails.com/China ; RESTAURANTS AND FAST FOOD Factsanddetails.com/China ; WEIRD FOODS IN CHINA NO. 1 Factsanddetails.com/China ; WEIRD FOODS IN CHINA NO. 2 Factsanddetails.com/China ; FOOD SAFETY IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; EATING AND DRINKING CUSTOMS IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

Restaurant Customs

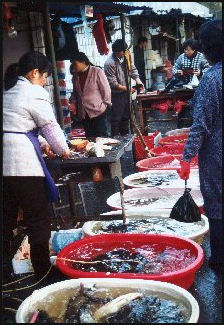

Shanghai fish market Some restaurants have menus written English but most don't. And even if know the name of a dish, you will often find that is prepared very differently from region to region and often from restaurant to restaurant. The easiest way to get a good meal is find a restaurant with a lot of customers, look around at what people are eating and point out to the waitress a dish that looks good. Sometimes the dishes don't taste like you think they will and sometimes other restaurant customers don't appreciate having their food stared at and pointed out, but all in all it is the best method for sampling a variety of good dishes. In small restaurants sometimes you often get a ticket and pay before eating.

Customers in restaurants in China are usually given chopsticks only but knives, spoons and forks are generally available if you ask for them. Servings are often very large and customers rarely eat everything. The soups in particular are often very big and large enough for two or three people to eat. Chinese sometimes appear rude to service personal at restaurants, hotels and stores — shouting and ordering people around. This kind of behavior is considered acceptable.

Smoking in restaurants is common. Many Chinese like to smoke when they eat. Some restaurant that have put up no smoking signs and tried to enforce it have lost lots of businesses There have been reports of some restaurants spiking their dishes with opium powder to get customers to come back. At crowded, busy restaurants, sharing tables with strangers is common. Restaurants generally serve water or tea for free. Sometimes no napkins are available.

Hygiene-wise and selection-wise the best palaces to eat are the restaurants at upscale hotels and good restaurants frequented by tourists. Many people worried about hygiene bring their own chopsticks or carry swabs and packets of alcohol to wipe off chopsticks and rims of glasses in restaurant.

Restaurant Hours: Between 11:00 and 3:00pm for lunch. Chinese generally eat lunch between noon and 1:30pm. Dinner is served beginning around 4:00pm. Chinese generally eat dinner between 6:00pm and 8:00pm. Restaurants often close before 8:00pm. Sometimes they stay open later in the large cities. They are often closed in mid-afternoon around 2:00 or 3:00pm to around 4:00pm.

Tipping and Customs About Who Pays at Restaurant in China

Splitting the bill is considered crude and barbaric. Being the one that pays it is considered an honor. According to Chinese custom the person that extends an invitation or the highest ranking person present is the person who pays. When there is a friendly argument over who pays, the most respected individual is expected to win out. The American-born, Taiwan-raised film director Bertha Bay-Sa Pan told the New York Times, “When the bill comes you have to put up a good fight to pay it, even if you don’t have enough money. Old-school Chinese never go Dutch.”

It is considered tacky for the host to pay in front of his guests, so usually what he does is excuse himself under the pretext of going to the bathroom and pays the bill privately. If a couple of friends meet by chance on the street and decide to go to a restaurant the two will vie with each other over who pays. The "loser" who doesn't pay often suggests going to another place and then paying the bill there.

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: If you want to it “is important that you intercept the bill before it reaches the table in order to assure others that you are able to pay for it. Others will show their respect for you by being very insistent that they pay. In order to alleviate the conflict over paying the bill, it is better to either arrange to have it paid separately by your assistant or to leave the room briefly before the meal is finished and take care of the paying at the counter. Avoid having the bill for the meal brought into the room in order to keep things under control. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Tipping is generally not practiced in China and can be seen as offensive. While tipping has become more common in restaurants in cities, it is generally not seen off the tourist trail. Tips are typically only given when doing tour-related activities or at hotels. Tax and service charges are usually not added to bills, except at some hotel restaurants and fancy restaurants, where 10 to 15 percent is surcharge is added. It is a good idea to bring cash. Many restaurants accept credits cards but some don't.

Restaurant Tips in China

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: The old adage of ‘if you want to be sure of good food, go where the locals go’ holds true in China. Whether expat or Chinese, the people who live in the city have suffered the bouts of food poisoning, bad service and being overcharged, giving them an informed view that is worth following. On a very basic level, that criteria involves going to restaurants where they can be sure they will not suffer ill health effects, followed by the finer points such as value for money, ambiance, food quality and service. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

“Some basic rules are when in Chinese restaurants, stick to dishes that their chefs have been trained to cook well, which typically means Chinese. There are good reasons that most vegetables are well cooked in China, from the way they are raised to the hygienic conditions in kitchens. One of the biggest risks that you can take is ordering a Western dish that includes raw vegetables from a Chinese kitchen.

In the first-tier cities of Shanghai, Beijing and Guangzhou, there are readily available monthly magazines and websites that offer credible restaurant listings and critiques. One of the better in Shanghai and Beijing is That’s, which also has a website. If you are in a less mapped area, ask for recommendations from the concierge at some of the better hotels in town or follow the crowds to find the better local restaurants.

Securing a Seat The average restaurant in China will not take a booking for less than ten people. Most mid-sized restaurants will have a general seating area and then a few small private rooms. A party of six people or more will typically book a private room where they will have dedicated wait staff, a nice atmosphere to visit and relax, and if they are lucky, their own karaoke setup. When booking a private room, it is common for the restaurant to ask for a minimum charge on food and drinks to be consumed. It is typically first come first serve, with preference given to regulars and friends of the owner or manager. You need to be fairly aggressive to secure a seat in a crowded restaurant. First you need to determine whether there is a host or hostess at reception. If there is, catch their eye and make sure that they are aware that you would like a table. Stay in front of them as much as possible to assure that you are seated when one becomes available. Others will have no qualms about taking a table that you move too slowly on. You will need to carefully track and defend your position.

Dining Out at Working-Class-Style Places in China

Reporting from Xinhuang, a town in rural Hunan Province, Jiayang Fan wrote in The New Yorker: “I wandered into the old town — tiny, serpentine alleys with sagging wooden Qing-dynasty houses that didn’t look much different from the way they might have two centuries ago. No one bothered to close their doors in the daytime, and inside I saw elders playing mah-jongg in unlit parlors next to altars for deceased relatives, often watched over by faded portraits of Chairman Mao. At the entrance to one alley, middle-aged men chain-smoked and played cards at round tables outside a restaurant. Everyone looked up as I entered, and I thought for a moment that I must be trespassing. I asked the proprietor, an aproned woman in her forties, if there was a menu, and she nodded, moving to the back of the room, past baskets of unwashed leafy vegetables. She yanked open a refrigerator door to display plastic containers of pig intestines, ears, and other offal. A pig’s head rolled slightly on the bottom shelf. After a somewhat confusing exchange, I was made to understand that this — the bloodied porcine array before me — was the menu. [Source: Jiayang Fan, The New Yorker, July 23, 2018]

“Whatever I picked she was happy to toss into the wok. (There was only one sauce.) Twenty minutes later, a steaming casserole appeared, for which, I later learned, I was scandalously overcharged. But that made sense: it was likely that everyone who had ever entered the restaurant was a local who knew the owners and knew exactly what would be served and how much it would cost. A menu assumes the availability of choices and the existence of strangers. Both were concepts that Xinhuang was only just beginning to embrace.”

David Sedaris wrote in The Guardian, “Most of the restaurants in China to me smelled dirty, though what I was smelling was likely some unfamiliar ingredient, and I was allowing the things I'd seen earlier in the day — the spitting and snot blowing, etc — to fill in the blanks. Then again, maybe not.” While on our trip we ate at normal, everyday places, and sometimes bought food on the street. Our only expensive meal was in Beijing, where we went alone to a fancy restaurant recommended by an acquaintance. The place was located in an old warehouse and had been lavishly decorated. There was a wine expert and someone whose job it was to drop by every three minutes and refill your water glass. We had the Peking duck, which was expertly carved rather than hacked and was served with little pancakes. Towards the end of the meal, I stepped into the men's room to pee and there, disintegrating in the western-style toilet, was an unflushed turd, a little reminder saying, "See, you're still in China!" I'll say that for China, though — offer to pay and before you can stab a rooster with a rusty screwdriver someone has taken you up on it. I think they want to catch you before you get sick, but whatever the reason, within minutes you're back on the street, searching the blighted horizon and wondering where your next meal might be coming from. [Source: David Sedaris, The Guardian July 15, 2011]

Chinese Restaurant Table Set Up and Serving Etiquette

A typical restaurant place setting includes chopsticks resting on a holder, a metal serving spoon, a large plate, a small plate and a small bowl with a porcelain spoon in it. Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: “At nicer restaurants, there will be a smaller plate nested in a larger one, and a single stand that both your chopsticks and a metal spoon rest against, instead of the porcelain spoon. In a restaurant with good service, the meal will begin with the waiter or waitress taking the paper cover off your chopsticks, tucking your napkin under your plate so that it drapes into your lap and offering you tea. There will be a rolled wet napkin to your left for you to wipe your hands before you begin eating. At some restaurants, the table setting includes a large plastic pack that encloses smaller packs that contain your chopsticks, a wet cloth, a paper napkin and toothpicks. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

"In a Chinese meal, most dishes are shared in the centre of the table. A meal typically starts with a number of small cold dishes. These are placed upon the table as you are first seated, to be nibbled at while the main dishes are being prepared. If there is a large group, a rotating glass disk (or a Lazy Susan) is placed in the centre of the table. It is turned constantly so that all the dishes are easily accessible to people sitting around the table. When the waiter or waitress first puts a dish on the table, it is customary for them to turn the glass disk so that people around the table can see the dish being presented. Depending upon the restaurant, if in a finer dining establishment, the waiting staff will then take the dish away and place individual servings into small dishes which are then either presented to you individually or are put upon the glass disk to be individually taken.

"During a meal, the glass disk is constantly being rotated on the table as people present dishes to each other. Chinese are customarily very considerate and polite of those around them and will give servings to people sitting on their right or left before taking food themselves. There is etiquette involved in using the rotating glass disk, which requires that before spinning the desired dish to its place in front of you, you first check to see if anyone else is taking food. You must wait until they are finished. Then you need to slowly rotate the dish you desire toward you, making sure to stop if people want to take something from one of the passing platters."

Eating at Restaurant in China

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: When eating Chinese food, it is customary to take only one or two bites of food at a time, and continue taking small portions as the dish passes you. You should first put the food onto the plate before putting it into your mouth. It is acceptable to dip the food down to just touch the dish and then put it in your mouth if you are in immediate need of a bite. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

“In eating ‘family style’, each person uses his or her own chopsticks to pick food out of a common serving dish. In a more formal environment, there are dedicated chopsticks and serving spoons that accompany each dish. You should use these to serve others and yourself, and then eat with your own chopsticks. If you would like to serve another person food using your chopsticks, the polite thing to do is to turn them over and use the end that you are not eating from to serve the other person. To show thoughtfulness to the people eating with you, especially if they are older or in a position of respect, it is usual to serve them before serving yourself. In a formal situation, everyone will wait for the guest of honour to take the first serving before they begin eating. If the person who seems to be taking charge of the meal spins a dish toward you and offers it, you are being honoured as a guest and should take a serving so that others at the table can also begin eating. If you would like to show your respect to someone else sitting at the table, instead of putting a serving on your own plate, put it on his or her plate instead.

“Rice or noodles accompany most meals, and they are usually served as one of the last dishes, eaten to ‘fill the empty corners of your stomach’. Many visitors to China prefer to have rice as an accompaniment for their meals, as it allows them to enjoy the sauces and combines starch with meats and vegetables in a way that they are more accustomed to. If you would like to have rice or noodles with the main dishes, you must ask the waiter or waitress to bring the rice earlier. It will normally not come until the very end. It is thought as good luck to have more food than you can eat. If you were trained by your parents to finish all of the food on your plate, you will be in agony by the end of the meal due to overeating.

“If you are with an aggressively well-mannered host or hostess, the only way to stop them from continuing to stuff food into you is to feign an inability to finish what is on your plate. You must also realise that a good Chinese meal or banquet is usually a marathon of food, rather than a sprint. Unlike the West where there may be three to five distinct courses, in China, dishes can keep coming one by one, for hours. A signal that you may be near the end of a meal or banquet is if soup is being It is usual in China for dessert to served. Soup and rice or noodles be served while the main dishes are usually the final dishes to are, sometimes in the last two be served. Midway through the or three dishes. There is not as much of a separation of the main meal, sweeter dishes may start meal and dessert as a person being served; although they are may be accustomed to in other dessert, the meal isn’t typically cultures. over until fruit is served.”

Restaurants in China with Supersize Menus

Sometimes hundreds of dishes are offered at restaurant in China. Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The menus at Da Dong,” a high-end restaurant chain in Beijing, “ are heftier than a small gym dumbbell — 5 pounds, 4 ounces [about 2½ kilograms], to be exact. Measuring 20 inches tall, 15 inches wide and more than an inch thick, the 140-page menu outweighs National Geographic's Global Atlas. Packed with rich color photos, the volume is divided into chapters with sumptuous red-and-white calligraphy paper. The brown binding bears the restaurant's name, and a table of contents listing about 200 dishes runs four pages. And diners are handed two other menus: a selection of seasonal items (24 pages) and a wine list (a relatively svelte 19 pages). [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, March 19, 2014 /^]

“Da Dong's massive menu may be among the most eye-popping in town, but it's hardly alone in its heftiness or artistic ambition. Even as a trend toward in-season and locally grown food has helped shrink the list of dishes at many au courant establishments in the United States and Europe in recent years, transforming their bills of fare into single-sheet affairs printed daily on ordinary paper, high-end restaurateurs in China have been supersizing./^\

“Middle-8th in Beijing, specializing in dishes from Yunnan province, employs a 128-page, 3-pound carte. At Pure Lotus, a pricey vegetarian hideaway, customers contend with a golden-paged volume stretching 2 1/2 feet wide and weighing 4 pounds, 5 ounces; and if that isn't enough, the nine-course $133 tasting menu is carved into an inch-thick wooden plank, also 2 1/2 feet wide. Countless run-of-the-mill restaurants offer customers menus as large and colorful as American high school yearbooks. /^\

“China's penchant for magnum opus-style menus is even spilling over to Western eateries here. Mr and Mrs Bund, Paul Pairet's haute French bistro in Shanghai, rated the top restaurant in mainland China by the Miele Guide for several years running, has embraced the concept with gusto, presenting a 20-page offering of about 150 items ranging in price from $6 to more than $130, with photos of almost every dish. "We were inspired by these Chinese menus," Pairet said. "Western menus, they try to avoid repetition, and the price range is very narrow, but we wanted to open it up." /^\

“Just why Chinese menus are growing in girth is a complex question rooted in cuisine, culture and commerce. The Middle Kingdom has great culinary diversity, and whereas Western cooking often relies on time-intensive techniques such as baking and roasting, Chinese cuisine tends to utilize a relatively finite number of ingredients, with chefs producing a multitude of dishes just by switching from boiling to sauteing or using a slightly different sauce. In addition, low labor costs in comparison with the West make it easier to have more cooks in the kitchen. Family-style ordering feeds a desire for selection, as do cooks eager to cater to diverse parochial palates, from the spicy-loving Sichuanese to the more delicate-dining Shanghainese. A culture of entertaining, whereby hosts show their generosity by ordering lavishly, also pushes restaurateurs to expand their offerings. /^\

“Dong Zhenxiang, the chef behind the 600-seat Da Dong, says he started adding photos to his menu in the early 1990s after winning designation from the local government as a "tourist class" restaurant as the nation shed Communist canteens and embraced capitalism. He found that foreigners as well as Chinese alike appreciated the visual guide. "Chinese dishes sometimes are very abstract when it comes to their names. Even Chinese people, if they don't know the story behind it, they'll find it hard to understand," he said. "Take, for example, The Dragon and Tiger Fight. It's fish and chicken. But if you don't know that, you don't know what's in it. A picture will show you.... Even I, as a professional chef, it's taken me years to realize why some dishes have their names." /^\

“As his menu grew more elaborate, Dong found himself in a predicament: Customers were pinching them at a pace that made running his restaurants difficult. "Ordinary customers and competitors would steal them; they would put them in their bags or under their coats. Waitresses would ask if they had taken them, and they'd just say 'no,' and we couldn't just search them," Dong recalled. "We need about 200 menus for each restaurant, and we'd get down to 100 and there wouldn't be enough to allow people to order." /^\

Red Restaurants

Kung Pao Chicken in London

The Daily Beast reported: “It’s a typical Saturday night at the Red Scene restaurant, which is packed with well-to-do Chinese diners. The younger ones clap in time to the music, while a gaggle of middle-aged patrons<many of them red-faced and tipsy — are on their feet, dancing and singing along with the stage performers. Tables groan under heaping platters of food. This could be any one of Beijing’s popular dinner shows, which draw audiences with the promise of Chinese opera or Western cabaret. But at Red Scene, the waiters and performers are all dressed as Red Army soldiers, Red Guards, workers, and peasants. And the skit is showcasing the persecution of an evil landlord, who is being beaten and forced to wear a pointed dunce cap — a scene straight out of China’s Cultural Revolution, one of the most tumultuous times in the nation’s history. The epoch remains controversial for a huge number of Chinese who were submitted to such “criticism sessions” — or even knew people who’d been “struggled” to death for being too bourgeois. [Source: The Daily Beast, February 19, 2011]

Such restaurants are part of a boom in Chinese tourism and entertainment venues catering to revolutionary nostalgia. To many, the idea of a Cultural Revolution’themed dining establishment is paradoxical, since tasty cuisine was certainly not that era’s strong suit. The first “Red restaurants” sprouted in Beijing in the “90s, offering little more than a few socialist-realist posters and food that was minimalist in the literal sense of the word. One served dandelion-leaf salad and raw cucumbers to symbolize the grass and bark that some poor Chinese ate during the hardscrabble “60s and “70s. Now Red-restaurant cuisine is more in line with middle-class tastes. In Mao’s hometown, “the Chairman’s Favorite” — roast fatty pork — is a must, while Red Scene offers a pricey shrimp dish for $27 alongside less-expensive cornmeal cakes and country-style bean curd. By Western standards, Red Scene’s clients aren’t big spenders — an average check is about $12 per person — but that isn’t mere peanuts for most Chinese, either.

The emergence of songs, dances, and vignettes evoking Cultural Revolution conflict is an equally significant change over the past decade. Before that, anything that exacerbated “class struggle,” or focused on the gap between the haves and the have-nots, was considered too sensitive for public airing. But Red Scene, which opened in 2005 and serves an average of 400 customers a night, is a good example of how many older Chinese have forgotten the dark side of that era<and how a younger generation never really knew it to begin with. During the skit vilifying an arrogant landlord, diners applauded and waved little red flags (conveniently provided by the wait staff).

This year, such “Red” venues are peaking in popularity because the Chinese Communist Party celebrated the 90th anniversary of its founding in July. Local governments are promoting “Red tours” to legendary sites along the Long March route, and organizers of a Red China Tourism Expo said such sites across the nation have received 1.35 billion visitors — or a fifth of all tourism traffic — in recent years. They expected a fivefold annual increase in 2011 over 2010 numbers.

Many of the Red-restaurant clientele were urban youths during the Cultural Revolution. In a nationwide campaign, they were sent to the countryside to reap the fruits of manual labor. These sojourns were often filled with long days of backbreaking work in the fields and lonely evenings. Still, many were inspired by communal life down on the farm. One such youth, Huang Zhen, decided to open Beijing’s Red Flag Fluttering restaurant in 2007, ‘so that people can remember the past,” he told Xinhua News Agency. Huang, now 58, instructed waiters to memorize Mao’s quotations and to dance the “loyalty dance” of the Cultural Revolution era, which involves a lot of fist-clenching to symbolize revolutionary ardor.

At Red Flag Fluttering, the majority of customers are in their 60s and 70s, usually arriving in groups to wallow in nostalgia for their years as youths “sent down” to the farm. “They like ... the revolutionary songs, dances, and pictures, [which] bring their memories back to their Cultural Revolution experiences,” explains one waiter. He says customers also like the Red-themed dishes, such as one called “A Revolutionary Big Family,” consisting of nearly a dozen types of seafood and meat, and “Warriors Who Dashed Over the Luding Bridge,” a dish of chicken named after the site of a famous Red Army victory. As for the skits on class struggle, the waiter shrugged. “We simply want our customers to be entertained and to recall their old experiences without thinking too deeply of these social issues.”

But the popularity of Red restaurants has also stirred controversy. One reader wrote in to a local paper to complain about Red Flag Fluttering. “The Red Guard uniforms are disgusting ... They remind me of the unpleasant past.” The reader said she’d gone to the restaurant with a dozen elderly friends, but “one of us who suffered a lot during the Cultural Revolution felt extremely uncomfortable. So we all left.” And how do authorities regard the restaurants? Although stage performances are subject to government censorship, there seems to be little official meddling so far. “We have nothing to do with the government, so we don’t care too much about its attitude,” says the waiter at Red Flag Fluttering. “As a matter of fact, we don’t even know the attitude of the government.”

Robot Restaurant in China

China's Dalu Robot restaurant, which opened in December 2010 in Jinan in the northern Shandong province, is touted as China's first robot hotpot eatery. Ken The of AP wrote: “Robots resembling Star Wars droids circle the room carrying trays of food in a conveyor belt-like system. More than a dozen robots operate in the restaurant as entertainers, servers, greeters and receptionists. Each robot has a motion sensor that tells it to stop when someone is in its path so customers can reach for dishes they want.” [Source:Ken Teh, AP, December 22, 2010]

Customers at the restaurant to praise the robots. "They have a better service attitude than humans," Li Xiaomei, 35, who was visiting the restaurant for the first time, told AP. "Humans can be temperamental or impatient, but they don't feel tired, they just keep working and moving round and round the restaurant all night."

Inspired by space exploration, robot technology and global innovation, the restaurant's owner, Zhang Yongpei, said he hoped his restaurant would show the world China was a serious competitor in developing technology. "I hope this new concept shows that China is forward-thinking and innovative," he said. Mr Zhang said he hoped to roll out 30 robots - which cost £3,870 each - in the coming months and eventually develop ones with human-like qualities that serve customers at their table and can walk up and down the stairs.

California Cuisine in Beijing

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Li Beiqi, a Chinese immigrant who returned from California in the late 1980s, opened a string of eateries called California Beef Noodle King U.S.A. A host of imitators soon jumped on the bandwagon and nowadays, if you head to a train station or shopping center food court, you're almost bound to see one of Li's shops (now simply called Mr. Li), or a branch of an imitator with the words California Beef Noodle prominently featured. (To my California tongue, the taste is 100 percent China.) Beef noodles, though, aren't the only "California" cuisine in China. There's a California Barbecue south of Tiananmen Square, and a place called California Aromatic Chicken Ltd. A chain of cafes called Hollywood offers up everything from waffles to teriyaki chicken, and for dessert there was (until recently) a shop known as Hollywood Squirrel Yogurt.” [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 21, 2015 ]

In February 2014, “Southern California natives Michael Tsai and Christian Jensen opened what many Angelenos might recognize as a more "real" L.A. restaurant in Beijing. Situated in a hutong, or historic alleyway, Palms L.A. serves Mexican-Korean fusion cuisine — think kimchi quesadillas — pioneered in Los Angeles by chefs such as Roy Choi. Cocktails include a blue-and-brown mix called "L.A. Water" and another dubbed "El Immigrante," made with yerba mate-infused vodka. The duo initially thought of opening a hot-pot restaurant, but realized the city was already packed with them and they needed a more distinctive theme. L.A. food trucks came to mind, and Palms L.A. was born.

“The restaurant has developed something of a cult following — Mayor Eric Garcetti and several City Council members paid a visit when they were in China in November. "The L.A. brand is a marquee brand here in China right now," Garcetti said. Tsai said he listens in on his Chinese customers' discussions of L.A. and how they view the city: a place with long, warm days, one that's romantic, idyllic and chic but laid-back. "We've been able to draw on that to strengthen our business," he said. "We want to make people feel like they're in L.A., whether it's the music or the food or the service, or just the overall experience of stepping out of the hutong and into Los Angeles, I think it's really a draw for a lot of people."

Image Sources: Beifan.com , Perrechon blog, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Wiki commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021