RICE IN CHINA

.jpg)

rice plants

Chinese consume about 200 million tons of rice a year, compared to 9 million tons in Japan. Over 70 percent of the rice grown in China come from one variety, a stain which is incredibly productive but only produces an abundant crop during the first generation. Because it is significantly less productive in successive generations, a new crop is planted in most cases at the beginning of every growing season. [Source: Peter White, National Geographic, May 1994]

Rice is the world's most important food crop and dietary staple, ahead of wheat, corn and bananas. It is the chief source of food for about 3 billion people, half of the world’s population, and accounts for 20 percent of all the calories that mankind consumes. In Asia, more than 2 billion people rely on rice for 60 to 70 percent of their calories. If consumption trends continue 4.6 billion people will consume rice in 2025 and production must increase 20 percent to keep up with demand.

Basic Chinese rice sells for about 50 cents a kilogram. Japanese-branded rice produced in China sells for about $1.50 a kilogram. Japan-produced rices sells for about $14 per kilogram. The cheapest rice in Japan sells for about $3 a kilogram. Rural Chinese rice cookers are often made of wood.

High-quality Chinese rice loses its taste in cold weather. “Guiba” is a crust of scorched rice scraped from the bottom of the pot. Toxic chemicals have been added to rice by some companies to make it whiter.

China is the world’s top consumer of grain.

See Separate Articles: FOOD IN CHINA: DIET, EATING HABITS AND TRENDS factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF FOOD IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOOD, DRINKS AND CANNABIS IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WORLD'S OLDEST RICE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE CUISINE factsanddetails.com ; VEGETABLES AND FRUIT IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FRUITS AND VEGETABLES IN ASIA AND SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com ; DURIANS AND MANGOSTEENS factsanddetails.com SNACKS, DESSERTS AND SWEETS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; REGIONAL CHINESE CUISINES factsanddetails.com ; FAMOUS CHINESE FOODS AND DISHES WITH INTERESTING, FUNNY NAMES factsanddetails.com ; EATING CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BANQUETS, PARTYING AND DRINKING CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RICE: ITS HISTORY, AGRICULTURE, PRODUCTION AND RESEARCH factsanddetails.com; RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; FIRST CROPS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; China.org Rice Culture Article china.org ; Eating China Blog eatingchina.com/blog ; Imperial Food, Chinese Government site china.org.cn; Wikipedia article on History of Chinese Food Wikipedia ; Chopstix chopstix.com ; Asia Recipe asiarecipe.com ; Chinese Food Recipes chinesefood-recipes.com : Food Tours in China, China Highlights China Highlights

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: The Story of Rice” by Xiaorong Zhang Amazon.com “Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking” by Fuchsia Dunlop Amazon.com; “A History of Rice in China” by Xiongsheng Zeng Amazon.com; “The Book of Tofu: Protein Source of the Future--Now!: A Cookbook by William Shurtleff Amazon.com; “The Ultimate Tofu Guide: The Tofu Book of History, Nutrition & Cooking” by Ellen EJ Kim Amazon.com; “Slippery Noodles” by Hsiang Ju Lin Amazon.com; “Xi'an Famous Foods: The Cuisine of Western China, from New York's Favorite Noodle Shop by Jason Wang , Jenny Huang, et al” Amazon.com; “Asian Ingredients: A Guide to the Foodstuffs of China, Japan, Korea, Thailand and Vietnam” by Bruce Cost Amazon.com

First Rice in China

The Jiahu — a rich but little known archeological site located near the village of Jiahu near the Yellow River in Henan Province in central China — has yielded the oldest known domesticated rice, dated to 7000 B.C. The rice was a kind of short-grained japonica rice. Scholars had previously thought the earliest domesticated rice belonged to the long-grain indica subspecies.

Other early evidence of rice farming comes from a 7000-year-old archeological site near the lower Yangtze River village of Hemudu in Zheijiang Province. When the rice grains were found there they were white but exposure to air turned them black in a matter minutes. These grains can now be seen at a museum in Hemudu. Some 8,000-year-old rice grains have been discovered in Changsa in the Hunan Province.

A team form South Korea’s Chungbuk National University announced that it had found the remains of rice grains in the Paleolithic site of Sorori, South Korea, dated to around 12,000 B.C. The discovery challenges the accepted belief that rice was first cultivated in China.

See Separate Articles: WORLD'S OLDEST RICE AND EARLY RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Rice as Food

.jpg)

Rice grains

The seeds in rice are contained in branching heads called panicles. Rice seeds, or grains, are 80 percent starch. The remainder is mostly water and small amounts of phosphorus, potassium, calcium and B vitamins.

Freshly harvested rice grains include a kernel made of an embryo (the heart of the seed), the endosperm that nourishes the embryo, a hull and several layers of bran which surround the kernel. White rice consumed by most people is made up exclusively of kernels. Brown rice is rice that retains a few nutritious layers of bran.

The bran and hull are removed in the milling process. In most places this residue is fed to livestock, but in Japan the bran is made into salad and cooking oil believed to prolong life. In Egypt and India it is made into soap. Eating unpolished rice prevents beriberi.

The texture of rice is determined by a component in the starch called amylose. If the amylose content is low (10 to 18 percent) the rice is soft and slightly sticky. If it is high (25 to 30 percent) the rice is harder and fluffy. Chinese, Koreans and Japanese prefer their rice on the sticky side. People in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan like theirs fluffy, while people in Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Europe and the United States like theirs in between. Laotians like their rice gluey (2 percent amylose).

See Separate Articles RICE: PLANT, CROP, FOOD, HISTORY AND AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com ; RICE PRODUCTION: EXPORTERS, IMPORTERS, PROCESSING AND RESEARCH factsanddetails.com

Fried Rice Recipe

Ingredients: 3 Tablespoons peanut oil; 4 cups boiled rice, cold; 1 teaspoon salt; ½ teaspoon black pepper; ½ a green, red, or yellow pepper, chopped; ½ cup mushrooms, sliced; ¼ cup water chestnuts, sliced; ½ cup bean sprouts; ¼ cup scallions, chopped; 3 eggs, beaten; ½ cup parsley, chopped. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of Foods and Recipes of the World, Gale Group, Inc., 2002]

Directions: 1) Cook rice according to instructions on package. 2) Allow to cool. 3) Heat the oil in a wok or skillet over high heat. 4) Add rice and fry until hot, stirring constantly. 5) Stir in salt and pepper. 6) Add the green pepper, mushrooms, water chestnuts, bean sprouts, and scallions, stirring often. 7) Push the mixture to the sides of the wok or skillet, making an empty space in the center of the rice mixture. 8) Pour beaten eggs into the empty space. 9) Let the eggs cook halfway through. 10) Blend the eggs with the rest of the rice mixture. 11) Heat until the eggs are fully cooked. 12) Remove the pan from heat. 13) Sprinkle the chopped parsley over each serving. Serves 4 to 6.

Tofu in China

Tofu is known as doufu or "vegetable meat" in China. Said to have been invented by a Chinese scholar in 164 B.C., it is made from coagulated soy milk produced by adding a coagulant salt to soaked, crushed and boiled soybeans and then pouring the mixture through a cheese cloth and pressing it with weights. In China, wiggly gelatinous tofu is fashioned into cakes and loaves, made into candy, and is shredded, sliced, deep fried, steamed, smoked, marinated, and fermented into a variety of products. [Source: Fred Hapgood, National Geographic, July 1987]

Tofu is known as doufu or "vegetable meat" in China. Said to have been invented by a Chinese scholar in 164 B.C., it is made from coagulated soy milk produced by adding a coagulant salt to soaked, crushed and boiled soybeans and then pouring the mixture through a cheese cloth and pressing it with weights. In China, wiggly gelatinous tofu is fashioned into cakes and loaves, made into candy, and is shredded, sliced, deep fried, steamed, smoked, marinated, and fermented into a variety of products. [Source: Fred Hapgood, National Geographic, July 1987]

Soybeans originally come from China. Tofu is an important source of protein in China, where arable land is in short supply and can not be wasted on raising animals. Tofu is usually made in the middle of the night and sold by shops and street vendors, who often start selling sliced one pound blocks at six in the morning and sell out within an hour. Deep fried tofu cooked on charcoal-fired woks. During the winter many people have a breakfast of hot soy bean milk.

Tofu and soybeans have woven their way into Chinese culture. The Chinese consider tofu as common but valuable and tofu sellers are regarded as poor men with good hearts. A girl who is beautiful but poor is known as “doufu-xishi” ("bean curd beauty") and a man who takes his wife for granted is just "eating her dofu." The true test of strength for a martial arts master is being able to thrust his arm elbow deep in a barrel filled with soybeans.

For Information Stinky Tofu See Separate Article FAMOUS CHINESE FOODS AND DISHES WITH INTERESTING, FUNNY NAMES factsanddetails.com ; Also See Separate Article SOYBEANS factsanddetails.com

Dumplings in China

There is an Incredible variety of dumplings — known in Mandarin as “jiao zi” (jee-Ow tsuh) — in China. There are culinary schools that specialize in them. Dumpling parties — in which everyone participates in making the dumplings and eating them — are a popular activity and often done as welcoming gesture for foreign guests.

dumpling stand By some accounts Chinese have been eating dumpling for 6,000 years. The fillings can be made from a variety of ingredients but is usually made with minced pork mixed with spices. To make a dumpling one puts a spoonful of mix on a dumpling skin, which is wrapped around the mixture, usually by hand, and either twisted like a Hershey’s kiss or folded together in a triangle and pinched and folded closed.

The wrappers for dumplings are typically made from dough — made only of flour and water — that is rolled very thin and cut into pieces, with the size varying depending on the kind of wrapper used. The filling is typically made of cabbage, Chinese cabbage, chives, spring onions, onions, ginger, garlic and ground pork. Seasoning for the filling is made from soy sauce, sesame oil, black pepper, spices, sesame seeds, MSG, and salt.

To make dumplings a spoonful of filling is placed into the wrapper which is folded and pinched close, depending on the region and style. The dumplings are cooked in a frying pan or steamer. In one frying method, oil is placed in the bottom of the pan, and the dumplings are placed on top with water added to one third the gyoza’s height. The flame is placed on high and the dumplings are cooked for six or seven minutes. When the water has evaporated the heat is turned down and a little sesame oil is added. The dipping sauce is made from 30 percent soy sauce, 70 percent vinegar and chili oil added to taste.

Shandong dumplings are said to among the best. They are fat and round. Qingdao, a city in Shandong, features dumplings with a slightly bitter taste produced by thistle tops.

Noodles in China

Noodles — “mian tiao” (MYAHN tee-wo) in Mandarin — are arguably the most popular food in China. Children are taught how to stretch dough into noodles at school and noodlemakers can make dozens of shapes ranging from "silk hair" to triangular. The noodle business is very competitive. There are more than 2,000 manufacturers of instant noodles.

Noodles are cheap, nutritious, and convenient. Dried noodles can be kept a long time without going bad. More than 100 different kinds of noodles are produced in Asia. More than 50 percent of the wheat consumption in the region is used in noodles.

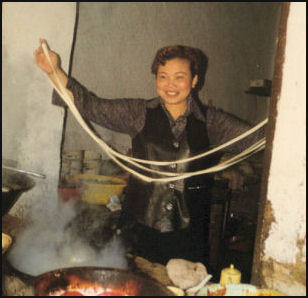

Making noodles

Unlike European pasta, which is pressed out a machine, Chinese noodles are kneaded, and then stretched and pulled into thin threads or rolled or sliced into flat ribbons. Describing a noodle maker at work in northern China Mike Edwards wrote in National Geographic, "He massaged a lump of dough, then drew it out to a length of about five feet. Then his arms flexed, his fingers twitched in cat’s cradle maneuvers, and suddenly the dough strands doubles, then quadruples and octuple."

There are hundreds of thousands of noodle shops in China. Many people insist that the best way to eat noodles is to slurp them directly into your throat without chewing them.

There are all kinds of regional variations. Shanxi is famous for its noodles. Pinched, curled or sliced, they are usually seasoned with malt vinegar and often consumed with shots of grappa-like Fen jui. Lanzhou in Gansu is famous for pliable, pulled noodles that are repeatedly wacked on a counter to make them “wake up” and then stretched into twirls and strings.

History of Noodles in China

Noodles have been consumed since 2000 B.C. A bowl with remarkably preserved yellow noodles dated to that period was unearthed at the Laija archeological site on the Yellow River. Found in a sealed earthenware bowl, the noodles were 50 centimeters long, 3 millimeters in diameter and resembled a traditional variety known as “la nian” that is still popular today. They appear to have been stretched by hand from dough made from millet.

Reported in the September 2005 issue of Nature and found by team sponsored by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the discovery means that noodles in China preceded pasta in Italy by at least 2,000 years. The origin of pasta is not known and has been variously attributed to the Chinese, Etruscans, Romans and Arab traders. An Etruscan mural dated to the 4th century B.C. shows servants mixing flour and water, along with a rolling pin and cutters. It is thought they were baking the dough rather than boiling it as is done when making noodles.

Boiled pasta is more likely to have reached Italy via the Arab world between the 5th and 8th centuries. The story that Marco Polo brought back the first pasta from China is a myth. Documents from 1279, sixteen years before Marco Polo returned from China, show that Genoese soldiers were carrying pasta in their provisions.

Noodles with Peanut Sauce Recipe

Ingredients: 2 Tablespoons peanut butter or sesame paste, smooth; ¼ cup hot water; 3 Tablespoons soy sauce; 1 teaspoon honey; 4 cups Chinese-style noodles or spaghetti, cooked; 2 scallions cut in ½-inch pieces (optional); Bean sprouts (optional); Chopped peanuts (optional). [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of Foods and Recipes of the World, Gale Group, Inc., 2002]

Directions: 1) Cook noodles according to package instructions and drain. ) In a large bowl, use a fork to stir the peanut butter or sesame paste with the water until it is creamy. ) Stir in the soy sauce and honey. Add the noodles to the peanut butter mixture and mix well. ) Refrigerate the mixture until ready to serve. ) Serve the noodles cold, topped with scallions, sprouts, or chopped peanuts. Eat with chopsticks. Serves 4.

Birthday Party Menu: Noodles with peanut sauce, Honey-glazed chicken wings, Steamed buns, Almond cookies

Instant Noodles in China

China is home to the world’s largest instant noodles market. The market was valued at $6.6 billion in 2008 — with China’s 1.3 billion people spending an average of $5 per person a year on them — and is expected to double to $13 billion by 2012. A pack of instant noodles cost between 1 yuan 5 yuan. A 41-year-old housewife in Shanghai told Reuters, “My husband and son love instant noodles. They eat them at breakfast and as a midnight snack more than twice a week.”

Adam Minter wrote in Bloomberg: “A crumpled instant-noodle bowl ground into the mud is an unlikely symbol of economic vitality. But during China's boom years those bowls were as ubiquitous around Chinese construction sites as the high-rise cranes above them. “That was no accident. For millions of Chinese workers, instant noodles were the convenient meal of choice, available for a few cents in every commissary and convenience store. And China's instant-noodle makers prospered. Between 2003 and 2008, annual instant-noodle sales expanded to $7.1 billion from $4.2 billion. [Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg, September 28, 2016]

The largest consumers of instant noodles in 2019 (servings per capita, total consumption): 1) South Korea (75.6 servings per person, 3, 900 millions of servings; 2) Nepal (58.4 servings per person, 1, 640 millions of servings; 3) Indonesia (46.8 servings per person, 12,520 millions of servings; 4) Japan (44.5 servings per person, 5, 630 millions of servings; 5) China (29.6 servings per person, 41, 450 millions of servings; a6 6) Australia (16.8 servings per person, 420 millions of servings; 7) Saudi Arabia (16.6 servings per person, 560 millions of servings; 8) the United States (14.2 servings per person, 4, 630 millions of servings; 9) United Kingdom; (6.3 servings per person, 420 millions of servings; Doesn’t include countries like Thailand, the Philippines and Taiwan. [Source: World Instant Noodles Association}

Old-fashion Noodle factory

Instant Noodle Business in China

Competition is in the instant noddle business is very fierce. A lot of energy goes into product development, advertising and distribution, There are dozens of companies scrambling for market share and brand recognition. They use colorful packaging, hire major celebrities to plug their products and are constantly introducing new flavors and trying out new recipes. Of late there has been a growing market for low-fat and nutritional versions of instant noodles which are generally deep fried before the are processed. High end, five-yuan-a-package varieties brands are also becoming increasing popular.

More than $237.4 million was spent on advertising instant noodles in 2006, a 19 percent increase from the previous year. The president of Uni-President brands, Taiwan’s largest food conglomerate, and the No. 3 noodle maker in China, told Reuters, “The core to our business is brand management.” The fight for shelve space in supermarkets and shops is sometimes called “noodle wars.”

Taiwan-founded Tingyi is far and a way the largest instant noodle maker in China. Its Master Kong brand holds a 43.3 percent market share. It closest rival, a Japanese joint venture Nissan Hualang, has a 14.2 percent share, followed by Uni-President with 10.5 percent, according to CIMB-GK Securities.

Tingyo owes its success to entering the market early and building strong brand loyalty. An analyst at CIMB-GK told Reuters, “Tingyo has been able to garner significant market share due to its distribution network. It’s not just about ads and pushing products through with promotional activities its really getting products through to customers. They got that part right. Tingyui has its plants located nears it distribution centers which enables it to get its products to markets quickly and smoothly.”

Decline of Instant Noodles in China

Adam Minter wrote in Bloomberg: ““But just as China's economy has slowed, so too has its appetite for instant noodles. Earlier this month, Tingyi, China's biggest noodle maker, was removed as a component of Hong Kong's Hang Seng Index after seeing its noodle profits drop 60 percent. China's instant-noodle sales are down 6.75 percent this year, the fourth consecutive year of decline. [Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg, September 28, 2016]

“The first problem is demographics. China's instant-noodle makers grew in parallel with an economic boom that was fueled by the migration of low-cost workers from the countryside. But China's working-age population has been in decline since 2010, and in 2015 the migrant population fell for the first time in 30 years. With more workers staying home, the incentive — and desire — to eat a prepackaged bowl of noodles was likely to decline, and it has. There's also the matter of the slowing economy. In 2015, sales growth of inexpensive food and consumer products hit a five-year low, according to a June study from Bain. Declines were particularly steep in products that cater to blue-collar workers, such as cheap beer (down 3.5 percent) and instant noodles — a phenomenon that Bain partly blames on Chinese jobs migrating to lower-wage countries.

“What's bad for noodle makers is great for many others. Rising wages have improved living standards and expectations for millions of Chinese workers. Pay a visit to a southern Chinese factory these days, and the food options are much improved. With employees becoming more scarce, benefits like better food are becoming increasingly important. China's workers are also able and willing to pay more for their day-to-day needs. According to one recent Chinese consumer survey, half of China's consumers now seek out the "best and most expensive" product. A 25-cent bowl of instant noodles doesn't make the grade.

“Then there are health concerns. Instant noodles have developed a nasty reputation in China thanks to scandals and rumors and a 2012 food-poisoning incident. There are long-standing allegations that noodles are contaminated with plasticizers. Legitimate or not, scandals don't help the reputation of a down-market product that's loaded with salt and preservatives.

“Even with these problems, instant noodles had the advantage of convenience. Now even that edge is being dulled. The streets of Chinese cities are swarmed by motorcycle and bicycle food-delivery men and women racing to deliver orders that are competitive in price with Chinese fast food. In 2015, the value of those deliveries was $20 billion — up 55 percent from 2014. Fast, healthier options are just an app away, even for students and factory workers.

“China's instant-noodle makers and importers are struggling to re-start growth. But these days there's competition from South Korea, with its far superior food-safety reputation. One option is to sell noodles to other emerging Asian economies such as Vietnam, where consumption is still growing along with the manufacturing sector. That won't make up for China's shrinking market, but China's new class of consumers don't offer more enticing options.

Image Sources: Beifan Louis Perrochon, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html, Dofu seller, All Posters Search Chinese Art

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021