ENVIRONMENT OF CHINA

Green poster from the 1920s

Economic growth has occurred at great cost to the environment, especially because China relies so much on energy-driven heavy industry to generate growth. China often seems that it is willing to put up with pollution to hold off joblessness. In the end it may be economic and political concerns that bring about the biggest changes. By some estimates pollution already slows economic growth by 3 percent a year.

China’s rapid economic growth, urbanization, and industrialization have been accompanied by steady deterioration of the environment in China. Both the air and water pollution in China have among the worst in the world, resulting damage to human health and lost agricultural productivity. Soil erosion, deforestation, and damage to wetlands and grasslands have degraded ecosystems and threaten agricultural sustainability. [Source: Robert Guang Tian and Camilla Hong Wang, Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

Environmental awareness is on the rise. Environmental laws are being taken more seriously. China, wrote historian Francis Fukayama. “may be the first country where demand for accountable government is driven primarily by concern over a poisoned environment.” The amount of money spent on pollution clean-up increased fivefold between 1985 and 1996. In 1998, spending on environmental protection exceeded one percent of gross nation product for the first time. By 2006 Beijing was spending $30 billion on the environment and cleaning up pollution.

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, ““Increasingly, though, Chinese anger is directed at the environmental degradation that has come with that growth. On one trip I drove through a village north of Beijing where signs strung across the road decried a new gold mine for destroying streams. A few miles later I came to the mine itself, where earlier that day peasants had torn up the parking lot, broken the windows, and scrawled graffiti across the walls. A Chinese government-sponsored report estimates that environmental abuse reduced the country's GDP growth by nearly a quarter in 2008. The official figures may say the economy is growing roughly 10 percent each year, but dealing with the bad air and water and lost farmland that come with that growth pares the figure to 7.5 percent. In 2005 Pan Yue, vice minister of environmental protection, said the country's economic "miracle will end soon, because the environment can no longer keep pace." But his efforts to incorporate a "green GDP" number into official statistics ran into opposition from Beijing.” [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

Environmental Performance Index: 28.4, 160th out of 180 countries (compared to top ranked Denmark with a score of 77.9 and last ranked India with a score of 18.9. The environmental performance index ranks countries on the basis of things like maintaining and improving air and water quality, maximizing biodiversity and cooperating with other countries on environmental problems. Prepared by researchers at Yale and Columbia in cooperation with the World Economic Forum, it is based on 75 measures including the number of children with respiratory diseases, fertility rates, water quality, overfishing, emissions of greenhouses gases, and the export of sodium dioxide, a key component of acid rain. [Source: Environmental Performance Index, Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy, 2022]

Happy Planet Index: 41.9, 94th out of 152 countries. Compiled by the British think-tank New Economics Foundation, It measures people’s well-being and their impact on the environment through data on life satisfaction, life expectancy and the amount of land required to sustain the population and absorb its energy consumption.. happyplanetindex.org/countries]

Websites and Sources: China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environmental Protection (MEP) english.mee.gov.cn EIN News Service’s China Environment News einnews.com/china/newsfeed-china-environment ; Greenpeace East Asia greenpeace.org/eastasia Green Power, Hong Kong greenpower.org.hk Earth Care, Hong Kong gfar.net Wikipedia article on Environment of China ; Wikipedia ; China Environmental Protection Foundation (a Chinese Government Organization) cepf.org.cn/cepf_english ; ; China Environmental News Blog (last post 2011) china-environmental-news.blogspot.com ;Global Environmental Institute (a Chinese non-profit NGO) geichina.org ; Greenpeace East Asia greenpeace.org/china/en ; China Digital Times Collection of Articles chinadigitaltimes.net ; International Fund for China’s Environment ifce.org

ARTICLES ON ENVIRONMENTAL TOPICS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ARTICLES ON ENERGY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ENVIRONMENT OF CHINA: PROBLEMS, ECONOMICS, COAL AND CLEAN CITIES factsanddetails.com ; COAL IN CHINA: PRODUCTION, DAILY LIFE, SOURCES AND CUTTING BACK ON IT factsanddetails.com; CHINA’S GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT factsanddetails.com ; GLOBAL WARMING AND CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COMBATING GLOBAL WARMING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; GARBAGE AND TRASH DISPOSAL IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RECYCLING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POLLUTION IN CHINA: MERCURY, LEAD, CANCER VILLAGES AND TAINTED FARM LAND factsanddetails.com ; COMBATING POLLUTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; AIR POLLUTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WATER POLLUTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DEFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DESERTIFICATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE GOVERNMENT, THE ENVIRONMENT AND NATIONAL PARKS factsanddetails.com ; ENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS AND ACTIVISTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ENVIRONMENTAL PROTESTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; OBSTACLES TO COMBATING POLLUTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Environmental Issues: “China's Environmental Challenges” by Judith Shapiro Amazon.com; “Environmental Issues in China Today: A View from Japan”by Hidefumi Imura Amazon.com; “China’s Engine of Environmental Collapse” by Richard Smith Amazon.com; “The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China's Future” by Elizabeth C. Economy Amazon.com; “The Environmental Issues in China: A Primer & Reference Source” by Min Wei and Timothy Fielding Amazon.com History: “China: Its Environment and History” by Robert B. Marks Amazon.com; “The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China” by Mark Elvin Amazon.com; “Mao's War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China” by Judith Shapiro Amazon.com

Environmental Problems in China

China has some serious environmental problems. It is estimated that the country has lost one-fifth of its agricultural land since 1949 due to economic development and soil erosion. The use of coal as a main energy source causes air pollution and contributes to acid rain. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Environmental problems in China in some cases are already at a critical level and they are getting worse. Rapid development has transformed huge swaths of the country into environmental wastelands. Acid rain corrodes the Great Wall; parts of the Grand Canal resemble open sewers; parts of Shanghai are slowly sinking because water beneath them has been sucked out; and some cities are so clogged with air pollution they don't appear in satellite pictures. Reports indicate that only 32 percent of China's industrial waste is treated in any sort of way. Already there are concerns of millions of environmental refugees in China and sulfurous rain clouds drifting from China to Japan and Korea.

The major current environmental issues in China are: 1) air pollution, mainly greenhouse gases and sulfur dioxide particulates from overreliance on coal; 2) water shortages, particularly in the north; water pollution from untreated wastes; 3) deforestation; 4) desertification; and 5) the illegal trade in endangered species. Deforestation has been a major contributor to China’s most significant natural disaster: flooding. In 1998 some 3,656 people died and 230 million people were affected by flooding. China’s national carbon dioxide emissions are among the highest in the world and increasing annually despite pledges to reduce them.

In conjunction with the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection annual report in 2010, Li Ganjie, the ministry’s vice minister. said biodiversity was declining with “a continuous loss and drain of genetic resources.” The countryside was becoming more polluted as dirty industries were moved out of cities and into rural areas. There were also signs that environmental neglect was causing instability. Protests in Inner Mongolia in 2011 were partly due to concerns that industries like coal and mining — largely dominated by ethnic Chinese — were destroying the grasslands used for herding by the indigenous Mongolians. Similar conflicts have arisen in Tibet and Xinjiang. [Source: Ian Johnson, Reuters, June 3, 2011] Canadian scholar Vaclav Smith, an expert of China's environment, has called China "the world's most worrisome case of environmental degradation." Travel writer Paul Theroux wrote: The Chinese, have “moved mountains, diverted rivers, wiped out the animals, eliminated the wilderness; they had subdued nature and had it screaming for mercy...In Chinese terms prosperity always spelled pollution.”

Causes and Costs of China's Environmental Problems

The main source of China's environmental problems is China’s greatest success — it phenomenal economic growth. Factories that dump pollutants into the air and water produce cheaper products than ones that filter out pollutants and treat waste water. It is hard to see the Chinese making sacrifices to improve their environment if it means slowing economic growth. Jennifer Turner of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars told Discover magazine, “What’s different about China is the scale and speed of pollution and environmental degradation...It’s like nothing the world has ever seen.”

Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The colossal industrial expansion of recent decades has depleted natural resources and polluted the skies and streams. China now consumes half the world's coal supply. It leads all nations in emissions of carbon dioxide, the main contributor to global warming. Pollutants from its smokestacks cause acid rain in Seoul and Tokyo. Within China, signs of environmental damage are pervasive: massive fish kills, lung-searing smog, denuded landscapes. They have stirred popular discontent and the beginnings of greater official concern for curbing pollution and preserving natural resources. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

The World Bank has calculated that pollution and associated health problems cost China 3 percent of GDP, with water pollution accounting for half of the losses. According to other estimates if sick days and forest and farmland loses are factored in environmental degradation may cost China as much 5 percent or even 10 percent of GNP. If these figures are true then real economic growth in China is between 5 percent and 7 percent not 10 percent and 11 percent.

In July 2013, according to the New York Times, an official Chinese news report said the cost of environmental degradation in China was about $230 billion in 2010, or 3.5 percent of the gross domestic product. The estimate, said to be partial, came from a research institute under the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and was three times the amount in 2004, in local currency terms. It was unclear to what extent those numbers took into account the costs of health care and premature deaths because of pollution. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, July 8, 2013]

Attitudes About Pollution in China

Confucianism offers a green world view in which the basic principals of harmony and balance are not limited to human society but are thought to extend to the universe as a whole. Asian philosophies as a whole stress the notion of harmony between nature and mankind but these philosophies are not always reflected in the Chinese record on environmentalism and pollution and their attitude about littering and eating wild animals.

Many Chinese are offended by the grim, hopeless tone in which articles on Chinese pollution are written in the West, and insist the Chinese are doing their best and they are doing a lot to improve the situation. The term “eco” is popular in China. Its kind of a fashion. Environmental awareness has grown significantly in China. Thomas Friedman wrote in the New York Times, “I believe this Chinese decision to go green is the 21st-century equivalent of the Soviet Union’s 1957 sputnik...When China decides to go green out necessity, watch out. You will not just be buying your toys from China. You will buy your next electric car, solar panels, batteries and energy efficient software from China...Right now , China is focusing on low-cost manufacturing of solar, wind and batteries and building the world’s biggest market for these products.”

Shi Zhengring, founder of solar-panel-maker Suntech, which is located in Wuxi near polluted Lake Tai, told Friedman, after a pollution disaster at the lake “the party secretary of Wuxi city came to me and said, “I want to support you to grow ths solar business into a $15 billion industry. So then we can shut down as many polluting and energy consuming companies in the region as soon as possible.” He is one of the a group of young Chinese leaders, very innovative and very revolutionary, on this issue. Something has changed, China realized it has no capacity to absorb all this waste. We have to grow without pollution.”

On attitudes about dangerous chemicals in a factory that made pleather (plastic leather), Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, “the workers believed that the product involved dangerous chemicals, and they thought it was dangerous to the liver. They said that a woman who planned to have children should not work on the assembly line...These ideas were absolutely standard; even teenagers fresh off the bus from the farm seemed to pick them up the moment they arrive in the city.” “There weren’t any warnings posted in factories, and I never saw a Lishui newspaper article about pleather; assembly line workers rarely read the newspaper anyway. They didn’t know anyone who became ill, and they couldn’t tell me whether there had been any scientific studies of the risks...Nevertheless their beliefs ran so deep that they shaped this particular industry. Virtually no young women worked on the assembly lines, and companies had to offer relatively high wages to attract anybody. At this plant you saw many older men — the kind of people who can’t get jobs at most Chinese factories.” When compared with the available data on plastic leather manufacturing many of suspicions raised in the rumors were backed by the data.

Qing Dynasty Roots of Chinese Environmental Protection

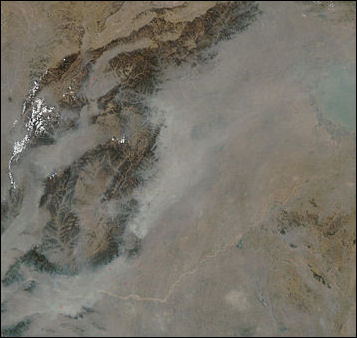

Pollution over east China“A World Trimmed With Fur: Wild Things, Pristine Places, and the Natural Fringes of Qing Rule,” is a book by the historian Jonathan Schlesinger, a scholar of imperial China at Indiana University in Bloomington, that analyzes the complex relationships among the exploitation of natural resources, environmental regulation and ethnic identity under the ruling Manchus during Qing dynasty (1644-1912). According to the New York Times: Mr. Schlesinger studied Manchurian and Mongolian archives to track the trade in furs, pearls and mushrooms across the Qing empire’s borderlands in the 18th and 19th centuries. He writes that Qing rulers created protected areas and limited harvests in response to environmental degradation and to reflect imperial politics that linked Manchu and Mongolian identity with a romanticized vision of unspoiled nature.

““The empire did not preserve nature in its borderlands; it invented it,” Mr.Schlesinger writes in the introduction. “The book documents the history of this invention and explores the environmental pressures and institutional frameworks that informed it.” In an interview, he discussed how Qing officials managed natural resources, their influence on conservation in contemporary China and the parallels between early conservation policies in China and the West.

Schlesinger told the New York Times; “The Qing court actually never quite settled on a single approach. Instead, its responses depended on the locality and the resource. In some cases, as with timber production in Mongolia, the court endorsed a licensing plan that could better control and capitalize on trade. In other cases, the court took the opposite approach and banned production altogether, as during Mongolia’s rush for wild mushrooms, when the court feared widespread poaching and undocumented migration were destroying the environment and Mongol way of life. Many historians argue that Chinese statecraft embraced a more pro-development attitude towards resource exploitation in these years. The real story is a bit more complicated. Preservationist policies often won out.

“There are some important differences between Qing environmental thought and our own. Qing subjects aimed to save their empire and its constituent parts, not the planet. They never justified their positions in terms of the sciences. They also lacked any umbrella organization or agency dedicated to managing the environment. In all of these respects, there are significant differences between modern environmentalism and what was practiced in the Qing world. That said, I do think, and try to show in the book, that many of the practices and concepts that were operative in the Qing — for example, the ways the court organized policies around “purity” in Mongolia and the idea of “nurturing the mussels” in Manchuria — were in many ways congruent with what you see in other parts of the world in the 19th century. In the Qing, ethnic identity profoundly informed environmental politics, and Qing officials justified environmental protection in part as a way of defending the Manchu and Mongol homelands — just as many in the German-speaking world saw nature protection as a pathway to redemption for the German “Volk,” and Americans called for national parks to preserve the country’s national spirit. This powerful connection between identity and environment is not unique to modern Western environmentalism. It has a more complicated past.

“One of the lessons is that there’s no place in China, or in countries around China, where there is unspoiled, pristine nature. If something appears to be unspoiled and pristine, chances are it’s because someone worked to make it that way at some point in time, and people have consistently worked to make it that way.” Changbaishan, a volcano on the border between North Korea and China, is a good example. the Manchus considered the lake inside the crater at the top to be holy territory. It was special because it was the birthplace of the Manchus. The court had special rules on collecting ginseng or trapping sable or other fur-bearing animals on the mountain. When British explorers first climbed the mountain in the late 1800s and early 1900s, they referred to it as untouched and unspoiled nature.In fact, it was very much touched. People had been poaching on the land, but the court had been using its resources to protect that territory. The People’s Republic of China has converted this space into a nature reserve. They are in many ways picking up where the Qing left off.

Economics, Unsustainability and the Chinese Environment

The Chinese government is no longer focused totally on economic growth. Increasingly, it has oriented towards meeting the needs of its people across a broad spectrum and this has meant has been forced to address the environmental consequences of its economic actions.. Guangdong Province, one of China’s richest and post productive economic areas, has enthusiastically embraced anti-pollution measures. It is also where job lay offs and factories closings have been occurring at a high rate. As part of its strategy to develop a “low-carbon economy” an effort is being made to move manufacturing to the countryside where jobs are still scarce and attract clean industries and services to the cities. Foreign company with clean energy technology are welcomed to use the area as a testing ground, with the government providing some of the services they need. Nationwide, thousands of factories that haven’t meet pollution standards have been shut down, putting millions of people out of work. Industries that have been allowed to stayed open say their costs have increased and their competitiveness has decreased as they have made upgrades to meet environmental standards.

The Chinese government is appropriating more money towards job-creating infrastructure projects rather technology-based environmental improvements. One of the main goals of economists and planners in China is to move the Chinese economy away from its dependence in environmentally-unfriendly manufacturing industries such as paper, chemicals and textiles and shift to less environmentally-disruptive economic sectors such as computing, biotechnology and science. China is at a disadvantage fighting pollution compared to developed countries in that those countries were already rich when they started fighting pollution, whereas China is still developing.

"China is involved in a race against time," Patrick Tyler wrote in the New York Times, "a race against the rapid depletion of the country's natural resources and the demands of its own population explosion." "If anybody's economic development is unsustainable, it's China's," one scholar told the Wall Street Journal, "Many people in the top leadership are aware that it's bad to develop and let the environment slip. But their hearts aren't in it." According to some estimates, China needs to spend around $50 billion over five years to make a dent in water and its air pollution problem. The problem is so severe that environmentalists in the U.S. are trying to get money earmarked for U.S. environmental problems reappropriated to China. "A billion dollars spent in the U.S. on equipment or technology would get you only a fraction of the progress you'd get with $1 billion in a country like China," one environmentalist said. See Water Pollution and the Chemical Industry Under Industries, Economics [Source: New York Times, Wall Street Journal]

Consumerism and the Environment in China

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, The richer China gets, the more it produces, because most of the things that go with wealth come with a gas tank or a plug. Any Chinese city is ringed with appliance stores; where once they offered electric fans, they now carry vibrating massage chairs.” [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

"People are moving into newly renovated apartments, so they want a pretty, new fridge," a clerk told National Geographic. "People had a two-door one, and now they want a three-door." The average Shanghainese household already has 1.9 air conditioners, not to mention 1.2 computers. Beijing registers 20,000 new cars a month. As Gong Huiming, a transportation program officer at the nonprofit Energy Foundation in Beijing, put it: "Everyone wants to get the freedom and the faster speed and the comfort of a car."

“That Chinese consumer revolution has barely begun,” wrote McKibben. “As of 2007, China had 22 cars for every 1,000 people, compared with 451 in the U.S. Once you leave the major cities, highways are often deserted and side roads are still filled with animals pulling carts.” "Mostly, China's concentrated on industrial development so far," said Deborah Seligsohn, who works in Beijing for the Washington, D.C.-based World Resources Institute. Those steel mills and cement plants have produced great clouds of carbon, and the government is working to make them more efficient. As the country's industrial base matures, their growth will slow. Consumers, on the other hand, show every sign of speeding up, and certainly no Westerner is in a position to scold.

Bill Valentino, a sustainability executive with the pharmaceutical giant Bayer who has long been based in Beijing, recently taught a high school class at one of the international schools. He had his students calculate their average carbon footprint, and they found that if everyone on the planet lived as they did, it would take two to four Earths' worth of raw materials to meet their needs. So they were already living unsustainable lives. Valentino — an expat American who flies often — then did the same exercise and found that if the whole world adopted his lifestyle, we'd require more than five planet Earths. hina has made a low-carbon economy a priority, but no one is under any illusion about the country's chief aim. By most estimates, China's economy needs to grow at least 8 percent a year to ensure social stability and continued communist rule. If growth flags, Chinese may well turn rebellious; there are estimates of as many as 100,000 demonstrations and strikes already each year. Many of them are to protest land takeovers, bad working conditions, and low wages, so the government's main hope is to keep producing enough good jobs to absorb a population still pouring out of the poor provinces with high hopes for urban prosperity.”

Coal-Fueled Growth and the Environment in China

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, That green effort, though, is being overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the coal-fueled growth. So for the time being, China's carbon emissions will continue to soar. I talked with dozens of energy experts, and not one of them predicted emissions would peak before 2030. Is there anything that could move that 2030 date significantly forward? I asked one expert in charge of a clean-energy program. "Everyone's looking, and no one is seeing anything," he said. [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

“Even reaching a 2030 peak may depend in part on the rapid adoption of technology for taking carbon dioxide out of the exhaust from coal-fired power plants and parking it underground in played-out mines and wells. No one knows yet if this can be done on the scale required. When I asked one scientist charged with developing such technology to guess, he said that by 2030 China might be sequestering 2 percent of the carbon dioxide its power plants produce.” Which means, given what scientists now predict about the timing of climate change, the greening of China will probably come too late to prevent more dramatic warming, and with it the melting of Himalayan glaciers, the rise of the seas, and the other horrors Chinese climatologists have long feared.

“It's a dark picture. Altering it in any real way will require change beyond China — most important, some kind of international agreement that transforms the economics of carbon. At the moment China is taking green strides that make sense for its economy.” "Why would they want to waste energy?" Deborah Seligsohn of the World Resources Institute asked, adding that "if the U.S. changed the game in a fundamental way — if it really committed to dramatic reductions — then China would look beyond its domestic interests and perhaps go much further." Perhaps it would embrace more expensive and speedier change. In the meantime China's growth will blast onward, a roaring fire that throws off green sparks but burns with ominous heat.

"To change people's minds is a very big task," Huang Ming said as we sat in the Sun-Moon Mansion. "We need time, we need to be patient. But the situation will not give us time." A floor below, he's built a museum for busts and paintings of his favorite world figures: Voltaire, Brutus, Molière, Michelangelo, Gandhi, Pericles, Sartre. If he — or anyone else — can somehow help green beat black in this epic Chinese race, he'll deserve a hallowed place near the front of that pantheon. Environmental journalist Bill McKibben is a scholar-in-residence at Middlebury College. Based in Shanghai, photographer Greg Girard has been documenting China since 1983.

Economic Hard Times and the Environment in China

Slow growth caused by the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 has had some positive environmental benefits: it reduced pollution and greenhouse emissions, primarily as a result of the drop in industrial production and construction, which in turn reduced the need for energy and materials that need electricity made by coal to produce.

An economic slowdown has actually been good for combating climate change.” Yang Fuqiang of the U.S.-based Energy Foundation told Reuters, “China is likely to achieve its emission-cutting target” in 2008 and 2009

Beijing saw some of its cleanest air in recent years during and after the Olympics when factories were idled and less vehicles were on the road. Around the same time Guangdong Province saw a significant drop in the number of badly polluted days, according to the Guangdong Provincial government, after 62,4000 businesses closed in 2008.

But as the Chinese economy began to sour as a result of the global economic crisis momentum that had been gained in the fight against pollution was lost as maintaining growth and providing jobs took a heightened importance. Peng Peng of the Guangzhou Academy of Social Sciences told the Washington Post, “With the poor economic situation officials are thinking twice about whether to close polluting factories, whether the benefits to the environment really outweigh the danger to social stability.”

Factories that were shut down or supposed to be shut down for environmental reasons were reopened or allowed to remain open. In February 2008 the Fuan textile factory, a multimillion dollar operation in Guangdong, was shut down for dumping waste from dyes into a river and turning the water red. It later quietly reopened in a new location. A large steel factory in the industrial city of Wuhan what was supposed to close in 2007 because of air pollution concerns remained opened and when last checked it was still belching out as much pollution as ever.

China's Green Cities

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, “Rizhao, in Shandong Province, is one of the hundreds of Chinese cities gearing up to really grow. The road into town is eight lanes wide, even though at the moment there's not much traffic. But the port, where great loads of iron ore arrive, is bustling, and Beijing has designated the shipping terminal as the "Eastern bridgehead of the new Euro-Asia continental bridge." A big sign exhorts the residents to "build a civilized city and be a civilized citizen." [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

In other words, Rizhao is the kind of place that has scientists around the world deeply worried — China's rapid expansion and newfound wealth are pushing carbon emissions ever higher. It's the kind of growth that helped China surge past the United States in the past decade to become the world's largest source of global warming gases. And yet, after lunch at the Guangdian Hotel, the city's chief engineer, Yu Haibo, led me to the roof of the restaurant for another view. First we clambered over the hotel's solar-thermal system, an array of vacuum tubes that takes the sun's energy and turns it into all the hot water the kitchen and 102 rooms can possibly use. Then, from the edge of the roof, we took in a view of the spreading skyline. On top of every single building for blocks around a similar solar array sprouted. Solar is in at least 95 percent of all the buildings, Yu said proudly. "Some people say 99 percent, but I'm shy to say that."

Whatever the percentage, it's impressive — outside Honolulu, no city in the U.S. breaks single digits or even comes close. And Rizhao's solar water heaters are not an aberration. China now leads the planet in the installation of renewable energy technology — its turbines catch the most wind, and its factories produce the most solar cells.

See Separate Article China’s Green Cities factsanddetails.com

Shenyang Turns Green

Christina Larson of Yale Environment 360 wrote in The Guardian: “Almost every day of his childhood, He Xin remembers the skies in his hometown of Shenyang being gray. "If I wore a white shirt to school, by the end of the day it would be brown," recalls He, who was born in 1974, "and there would be a ring of black soot under the collar." He grew up in Shenyang (population 8 million), the capital of northeastern China's Liaoning province, a city famous for its heavy industry and manufacturing — and soot and pollution. Growing up, the view he remembers most vividly was looking out over Shenyang's fabled Tiexi industrial district, home to several large iron and steel plants and the site of China's first model workers village: "When I was a teenager, if I climbed a tall building to look out over Tiexi, all I would see was a forest of large smokestacks, chimneys, and dark, billowing smoke." [Source: Christina Larson, Yale Environment 360, part of the Guardian Environment Network, October 17, 2011]

But today all that is gone. No longer standing are Tiexi's iconic smokestacks and its blocks of red brick workers' dormitories, with their rows of coal-fired chimneys atop. Now He is the vice president of the environmental consultancy BioHaven and splits his time between Shenyang, Beijing, and St. Louis. To him, Shenyang looks almost unrecognizable today. "It's not perfect, but the air is cleaner... almost like it's not in China," he said, adding: "The only thing the same is the statue of Chairman Mao." He was referring to the saluting bronze figure that still dominates downtown People's Park, one of the largest statues of Mao Zedong in China.

If the city long known as the "elder brother" of industry for its central role in Mao's drive to industrialize China in the 1950s and '60s has recently made strides to clean up its act, He isn't the only one to take notice. Last November, the Urban China Initiative (UCI) , a think tank co-founded by McKinsey & Co., Columbia University, and Beijing's Tsinghua University, released its first "Urban Sustainability Index " for China. The index assessed sustainability in 112 cities by looking at 18 environmental indicators — from air pollution to waste recycling to mass transit — for the years 2004-2008. Among Chinese cities, Shenyang emerged as a leader in environmental improvement.

According to UCI's research, Shenyang had removed virtually all traces of heavy industry from its core by 2010. In new residential areas, coal heating had been replaced by natural gas. Urban green space had increased 30 percent from 2005 to 2007. Perhaps most significantly, the heavy industry that does operate in the city — now relocated to facilities in the outer suburbs — is significantly less polluting than heavy industry elsewhere in China: Shenyang's plants emit about one-fifth the level of sulfur oxides as the national average in China. The reason, quite simply, is that the city tore down most of its old factories and literally started again, with newer facilities and desulfurization equipment. "The evolution is significant," Jonathan Woetzel, a director in McKinsey's Shanghai office, told me.

For large infrastructure projects, Shenyang has also benefited from the ability of its savvy and well-connected leaders to make their case in Beijing. Each year, the central government announces a pot of money for new municipal infrastructure projects that cities can bid for. The details of how money is transferred are opaque to outsiders. But Shenyang, ever a stronghold of the political establishment, has fared well. For instance, the city recently received a slice of funding from Beijing for its subway system, now under construction; the first line opened in 2010, and the second line is scheduled to open next year.

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see “How a smoggy Chinese city turned green” by Christina Larson in The Guardian theguardian.com/environment

China’s Ecosystems Improving, Study Says

A paper, authored by U.S. and Chinese researchers published in the June 2016 issue of Science, found that China’s ecosystems have become healthier and more resilient against disasters such as sandstorms and flooding. The authors partly credit what they describe as the world’s largest government-backed effort to restore natural habitats such as forests and grasslands, totaling some $150 billion in spending since 2000. “In a more and more turbulent world, with climate change unfolding, it’s really crucial to measure these kinds of things,” says Gretchen Daily, a Stanford biology professor and a senior author on the paper. The study didn’t examine air, water or soil quality, all deeply entrenched problems for the country.[Source: Te-Ping Chen, China Real Time, Wall Street Journal, June 17, 2016]

Te-Ping Chen wrote in the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time: ““Beijing’s investments in promoting better ecosystem protection were triggered after a spate of disasters in the 1990s. In particular, authors note, two decades after China started to liberalize its economy, rampant deforestation and soil erosion triggered devastating floods along the Yangtze River in 1998, killing thousands and causing some $36 billion in property damage. The government subsequently embarked on an effort to try to forestall such environmental catastrophes. According to the study, in the decade following, carbon sequestration went up 23 percent, soil retention went up 13 percent and flood mitigation by 13 percent, with sandstorm prevention up by 6 percent.

Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the University of Minnesota and other institutions were involved in the study. Data was collected by remote sensing and a team of some 3,000 scientists across China. Reforestation was one particular bright spot, Daily said. Under Mao Zedong, China razed acres of forests to fuel steel-smelting furnaces. To reverse the trend–and combat creeping desertification in the country’s north — the country embarked on a project in 1978 to build a “Great Green Wall” of trees. Today, authorities say that 22 percent of the country is covered by forest, up 1.3 percentage points compared with 2008. The authors note that the study has limits. While China has reported improving levels of air quality in the past year, urban residents still choke under regular “airpocalypses.” The majority of Chinese cities endure levels of smog that exceed both Chinese and World Health Organization health standards.“You can plant trees till the end of time,” says Ms. Daily. “But they’ll never be enough to clean up the air.”

Last updated June 2022

Image Sources: 1) Ohio State University; 2) Gary Baasch; 3) Environmental News; 4) Johomaps; 5) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; 6) Guardian, Environmental News; 7) Bucklin archives ; 8) Agroecology; 9) Kyodo, Environmental News ; 10)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2022