DESERTIFICATION IN CHINA

Loess Plateau

About 20 percent to 28 percent of China is covered by desert and that amount of desert in China is getting larger every year. Deserts are being created faster in China than anywhere else in the world, with old deserts expanding and new deserts being formed. The rate of desertification nationwide is around 2,330 square kilometers (900 square miles) to 3,370 square kilometers (1,300 square miles) a year, an area nearly the size of Rhode Island, with an area the size of New Jersey becoming desert every five years. The situation is improving though . About 3,400 square kilometers per year was lost in the 1990s. The rate slowed to 1,300 square kilometers per year in the 2002. At the same time tree-planting and other anti-desertification efforts have reclaimed lands from the desert.

There is some debate over rate of desertification and how much land has become desert in China. According to the New York Times: Climate change and human activities have accelerated desertification. China says government efforts to relocate residents, plant trees and limit herding have slowed or reversed desert growth in some areas. But the usefulness of those policies is debated by scientists, and deserts are expanding in critical regions. Drought across the northern region is getting worse. One recent estimate said China had 21,000 square miles more desert than what existed in 1975 — about the size of Croatia." Tengger Desert near Beijing has expanded and "is merging with two other deserts to form a vast sea of sand that could become uninhabitable. [Source: Josh Haner, Edward Wong, Derek Watkins and Jeremy White New York Times, October 24, 2016]

Agro-economist Lester Brown said that around 24,000 villages in China's north-west have been totally or partially abandoned since 1950. "China is now at war. It is not invading armies that are claiming its territory, but expanding deserts," he wrote recently. "Old deserts are advancing and new ones are forming like guerrilla forces striking unexpectedly, forcing Beijing to fight on several fronts. And in this war with the deserts, China is losing." [Source: AFP, November 1, 2011]

In western China the huge Taklimakan and Kumtag deserts are expanding at such a high rate they are expected to merge in the not too distant future. Two deserts in Inner Mongolia and Gansu Province are also in the process of reaching each other and merging. The Gobi grew by 52,400 square kilometers (20,000 square miles), an area half the size of Pennsylvania, between 1994 and 1999, and continues to advance at a rate of two miles a year and is now only 240 kilometers or so from Beijing. Hardest hit are poor and dry provinces such as Ningxia and Qinghai, whose populations have shrunken to respectively 6.30 million and 5.63 million in the past decade [Source: Guardian, January 4 2011]

The Chengdu plain, one of China’s primary grain-growing areas, is threatened by sands from the Ruoergai grasslands. The grasslands were a rich grazing areas until a few decades ago when cows and goats began to multiply and overgraze the land. There is danger that a dust bowl situation could develop. Already wells have dried up and emergency grain supplies have to be brought in to keep people from starving. Many people are being encouraged to move to more hospitable lands.

See Separate Articles DEFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COMBATING DESERTIFICATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com TORNADOES, LIGHTNING AND SAND, DUST, AND SNOW STORMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DROUGHTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com RAINMAKING AND MAN-MADE WEATHER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:Aridity Trend in Northern China” by Congbin Fu and Huiting Mao Amazon.com; “China's Water Crisis” by Jun Ma , Nancy Yang Liu, et al. (2004) Amazon.com; “China's Water Resources Management: A Long March to Sustainability” by Seungho Lee (2021) Amazon.com; “Water Resources Management of the People’s Republic of China: Framework, Reform and Implementation” by Dajun Shen Amazon.com “Managing Water on China's Farms: Institutions, Policies and the Transformation of Irrigation under Scarcity” by Jinxia Wang, Qiuqiong Huang, et al. (2016) Amazon.com; Environmental Issues: “China's Environmental Challenges” by Judith Shapiro Amazon.com; “Environmental Issues in China Today: A View from Japan”by Hidefumi Imura Amazon.com; “China’s Engine of Environmental Collapse” by Richard Smith Amazon.com; “The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China's Future” by Elizabeth C. Economy Amazon.com; “The Environmental Issues in China: A Primer & Reference Source” by Min Wei and Timothy Fielding Amazon.com History: “China: Its Environment and History” by Robert B. Marks Amazon.com; “The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China” by Mark Elvin Amazon.com; “Mao's War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China” by Judith Shapiro Amazon.com

Causes of Desertification in China

Gobi dust storm

The main causes of desertification are overgrazing, overplanting , overplowing and raising crops in regions too dry for crops. These problems in turn are result of population pressures on marginal land. The problem is somewhat analogous to what happens in areas that have been deforested. Once an area is degraded people move onto a new area and degrade that while the old area takes decades to recover or never does. Dr. Sing Yuqin of Beijing University told the New York Times, "Once the process gets started it tends to expand exponentially. And the people are pushed into a poverty trap from which it's hard to escape."

Desertification is caused primarily by human activities. One of the main culprits of the desertification in the Mao era was Mao's plan to raise grain in areas where grain didn't grow well, such as Inner Mongolia. This deprived the land of grass which prevented soil being blown away by the fierce winds that ravage this region. The grassland has been likened to the thin skin on a bun. It can be destroyed if a couple of centimeters is disturbed. One Mongolian said, “Our leaders used to say we should never cultivate the grassland.” Greenpeace argues that grass seeding and stricter land management are the best way to reclaim the land.

Poor land use and overgrazing are causing large areas of grasslands north of Beijing and in Inner Mongolia and Qinghai province to turn into a desert. One man who lived in a village on the eastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau that was being swallowed up by sand told the New York Times, "The pasture here used to be so green and rich. But now the grass is disappearing and the sand is coming.”

Some believe that desertification has been caused by climate changes. Scientist in Qinghai have recorded higher temperatures, lower rainfall and stronger winds since the 1950s. Persistent drought robs the soil of moisture and makes it easer for the soil to be picked up and carried away by wind. In Inner Mongolia, global warming appears to have made the region drier.

Overgrazing, Overplanting and Desertification in China

Desertification in China is caused largely by overgrazing. Huge flocks of sheep and goats strip the land of vegetation. In Xillinggol Prefecture in Inner Mongolia, for example, the livestock population increased from 2 million in 1977 to 18 million in 2000, turning one third of the grassland area to desert. Unless something is done the entire prefecture could be uninhabitable by 2020.

Overgrazing is exacerbated by a sociological phenomena called "the tragedy of the common." People share land but raise animals for themselves and try to enrich themselves by raising as many as they can. This leads to more animals than the land can support. One grassland in Qinghai that can support 3.7 million sheep had 5.5 million sheep in 1997

Animals remove the vegetation and winds finished the job by blowing away the top soil, transforming grasslands into desert. When a herder was asked why he was grazing goats next to a sign that said “Protect vegetation, no grazing,” he said, “The lands are too infertile to grow crops — herding is the only way for us to survive.”

China has more goats and sheep than any other country —and there numbers increased as desertification did. There were over 300 million sheep and goats in China in the 2000s,, compared to 8 million in the United States. The number of cattle, sheep and goats tripled between 1950 and 2003. Sheep and goats are China's most important grazing animals. Most of these animals are bred in the semiarid steppes and deserts in the north, west, and northwest. The number of sheep and goats has expanded steadily from about 42 million in 1949 to approximately 156 million in 1985. Overgrazed, fragile rangelands have been seriously threatened by erosion, and in the late 1980s authorities were in the midst of a campaign to improve pastures and rangelands and limit erosion. [Source: Library of Congress]

Dazhai Way Agriculture Damage on the Loess Plateau

The Loess Plateau is a region in northern China about the size of France, Belgium and the Netherlands combined. Loess is compacted dust and silt. In the case of Loess Plateau it originated in the deserts to the west and was carried to central China by strong westerly winds for hundreds of thousands of years. In some places the loess is hundreds of meters thick. Erosion is a serious problems. Rains and winds carry the loess into the Yellow River and the air.

Charles C. Mann wrote in National Geographic, Zhang Liubao whacked “the eroded terraces of his farm into shape with a shovel — something he'd been doing after every rain for more than 40 years. In the 1960s, Zhang had been sent to the village of Dazhai, 200 miles to the east, to learn the Dazhai Way — an agricultural system China's leaders believed would transform the nation. In Dazhai, Zhang told me proudly, "China learned everything about how to work the land." Which is true, but not, alas, in the way Zhang intended. [Source: Charles C. Mann, National Geographic, September 2008]

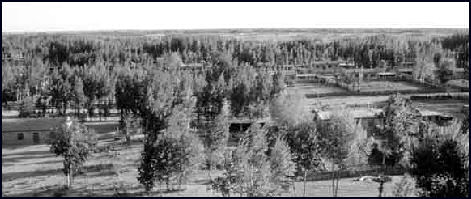

An area of Inner Mongolia before desertification

“After floods ravaged Dazhai in 1963, the village's Communist Party secretary refused any aid from the state, instead promising to create a newer, more productive village. Harvests soared, and Beijing sent observers to learn how to replicate Dazhai's methods. What they saw was spade-wielding peasants terracing the loess hills from top to bottom, devoting their rest breaks to reading Mao Zedong's little red book of revolutionary proverbs. Delighted by their fervor, Mao bused thousands of village representatives to the settlement, Zhang among them. The atmosphere was cultlike; one group walked for two weeks just to view the calluses on a Dazhai laborer's hands. Mainly Zhang learned there that China needed him to produce grain from every scrap of land. Slogans, ever present in Maoist China, explained how to do it: Move Hills, Fill Gullies, and Create Plains! Destroy Forests, Open Wastelands! In Agriculture, Learn From Dazhai!”

“Zhang Liubao returned from Dazhai to his home village of Zuitou full of inspiration. Zuitou was so impoverished, he told me, that people ate just one or two good meals a year. Following Zhang's instructions, villagers fanned out, cutting the scrubby trees on the hillsides, slicing the slopes into earthen terraces, and planting millet on every newly created flat surface. Despite constant hunger, people worked all day and then lit lanterns and worked at night. Ultimately, Zhang said, they increased Zuitou's farmland by "about a fifth" — a lot in a poor place.”

“The actual effect was to create a vicious circle, according to Vaclav Smil, a University of Manitoba geographer who has long studied China's environment. Zuitou's terrace walls, made of nothing but packed silt, continually fell apart; hence Zhang's need to constantly shore up collapsing terraces. Even when the terraces didn't erode, rains sluiced away the nutrients and organic matter in the soil. After the initial rise, harvests started dropping. To maintain yields, farmers cleared and terraced new land, which washed away in turn. The consequences were dire. Declining harvests on worsening soil forced huge numbers of farmers to become migrants. Partly for this reason, Zuitou lost half of its population. "It must be one of the greatest wastes of human labor in history," Smil says. "Tens of millions of people forced to work night and day on projects that a child could have seen were a terrible stupidity. Cutting down trees and planting grain on steep slopes — how could that be a good idea?"

See Loess Plateau Under LAND AND GEOGRAPHY OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

Chinese Desertification Refugees

Desertification has caused millions of rural Chinese to abandon unproductive land in Gansu, Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Provinces and migrate eastward. A study by the Asian Development Bank found 4,000 villages at risk of being swallowed up by drifting sand. Already a migration on the scale of the Dust Bowl in the United States in the 1930 has taken place in China. The only problem is that in China there is no California to escape to. Many of those driven off land degraded by desertification have ended up in eastern cities as migrant workers.

In parts of the Ningxia Province, significant rain has not fallen for years and farming is impossible. Tens of thousands of people from villages mostly in poor southern Ningxia have been resettled to 215,000 acres of newly irrigated land near the Yellow River in north central China. The exodus took place between 1998 and 2000 and cost about $325 million. About 70 percent of those affected are Huis. Planners had originally hoped to resettle a million people (20 percent of Ningxia's total population) but there was enough money available to handle that many people.

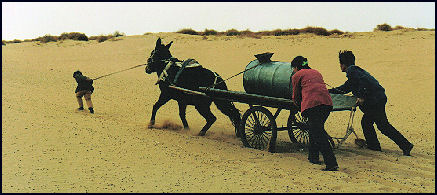

An area of Inner Mongolia after desertification

Jonathan Watts wrote in The Guardian. “Millions of Chinese eco-refugees have been resettled because their home environments degraded to the point where they were no longer fit for human habitation. The government says more than 150 million people will have to be moved in the future. Water shortages exacerbated by over-irrigation and climate change are the main cause. The problem is most severe in the north-west, where desert sands are swallowing up farmland, homes and towns. One place known as an “ecological disaster area” is Mingqin, a shrinking oasis area In Gansu Province. Here the Yellow River has been diverted more than 100 kilometers to replenish dried-up reservoirs and aquifers in Minqin, where the population has swollen from 860,000 to 2.3 million over the last 60 years, even as water supplies have declined. [Source:Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, May 18, 2009]

On top of that the Tengger desert is encroaching from the south-east and the Badain Jaran desert from the north-west. Since 1950 the oasis has shrunk by 111 square miles (288 sq km), while the number of annual superdust storms has increased more than fourfold. In Liangzhou district, 240 of the 291 springs have dried up. Global warming is adding to the problem. Evaporation rates are rising, along with temperatures. According to a study by the Center for Agricultural Water Research in China, 64 percent of the reduced stream-flow in the area is attributable to climate variation.

Relocation of Chinese Desertification Refugee

Some of these people are not so happy about the move. One man who went from living in a yurt herding to 300 sheep on a plain in Inner Mongolia to living in a brick houses and raising dairy cows told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “My income was cut to two-thirds what it was. Living on the plain was free and comfortable.”

One person that lives in Mingqin is a man named Huang Cuikin. Huang told The Guardian dust storms hit his village more often than in the past. The water table is falling. Temperatures rise year by year. Yet Huang says this is an improvement. In 2006 he was relocated here by the government from an area where the river ran dry and the well became so salinated that people who drank from it fell sick.

Huang is one of thousand who the government has paid to move from the worst affected areas.”Life is easier now,” Huang told The Guardian, puffing on a cigarette in the new brick home that the authorities have given him. “When we lived in Donghuzhen, we had little water and the crops couldn't grow. Our income was tiny and we were very poor.” The government has given him a new home and land, but the desert winds still howl outside the door and his fields are bordered by sand dunes. Workers in the fields wear masks to protect their faces from the dust storms that whip in from the dunes.

Huang told The Guardian he likes his new home, but with the climate getting hotter and drier, he cannot be complacent that it is secure from the sands. It's just two or three kilometers from here to the desert, says Huang, so we have taken every measure we can think of to stop the desert moving closer. To survive, we must control the desert. Huang know the trees alone cannot save his home. “In Minqin, our greatest need is water. That is our lifeline. Without water, we cannot survive.”

Farming is no piece of cake either. When the desert winds tear up the sands outside his front door, says he is choked by dust, visibility falls to a few meters and the crops are ruined. “We have taken every measure we can think of to stop the desert moving closer and submerging our crops and villages,” he said.

Climate Change and Desertification in China

David Stanway of Reuters wrote: “Experts say China's reforestation work has become more sophisticated over the years, the government benefiting from decades of experience and able to mobilise thousands of volunteers to plant trees. But the fight is far from over, they add, with climate change set to worsen conditions for farmers living in the arid north. "They have been living in similar conditions for generations,"said Ma Lichao, China country director for the Forest Stewardship Council, a non-profit organisation promoting sustainable forest management. "But it is very important to say that climate change is something very new." [Source: David Stanway, Reuters, June 3, 2021]

In March 2021 “heavy sandstorms hit Beijing for the first time in six years, putting the country's reforestation efforts under scrutiny, with land increasingly scarce and trees no longer able to offset the impact of climate change. Ma said the sandstorms that hit Beijing in March did not mean planting trees had failed, but showed it would no longer be enough to offset the impact of climate change. "To be honest, I don't think the trees can help the situation," he said.

Li Jianjun of the China National Environmental Monitoring Center said temperatures in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia have been 2-6 degrees Celsius higher than normal since February, with the melting snow exposing more sand to the wind. Some of the farmers in Wuwei have begun to lose hope after decades trying to subdue the deserts. Ding Yinhua, a 69-year-old shepherd, told Reuters, the sandstorms were so severe that sometimes she didn't dare open her eyes.

“Despite the tree-planting, pastures have deteriorated in recent years as a result of declining rainfall in the spring and summer, she added. "It's just no good without rain. We don't have land so there's no other way: we just herd sheep. In 2015 and 2016, there was rain but since then there's been nothing, and you now have to wait until September," she said. Her husband, Li Youfu, 71, said he thought tree-planting had made no difference at all. "The sand is still moving. This can't be controlled," he said. "When the wind comes, it's usually really strong. No one can stop it."

Living Amid Desertification Not So Far From Beijing

The Tengger Desert, lies on the southern edge of the massive Gobi Desert, not far from major cities like Beijing. The Tengger is growing. Liu Jiali, 4, lives in the Tengger in an area called Alxa League, where the government has relocated about 30,000 people, who are called “ecological migrants,” because of desertification. Like Jiali’s family, many people herd animals and run small tourist parks on the edge of the Tengger Desert. Many people in this area are from families that fled Minqin, at the western end of the Tengger Desert, during China’s Great Famine from 1958 to 1962, when tens of millions died.[Source: Josh Haner, Edward Wong, Derek Watkins and Jeremy White New York Times, October 24, 2016]

“Across northern China, generations of families have made a living herding animals on the edge of the desert. Officials say that along with climate change, overgrazing is contributing to the desert’s growth. But some experiments suggest moderate grazing may actually mitigate the effects of climate change on grasslands, and China’s herder relocation policies could be undermining that.

“Officials have given Jiali and her family a home in a village about six miles from Swan Lake, the oasis where they run a tourist park. To get them to move and sell off their herd of more than 70 sheep, 30 cows and eight camels, the officials have offered an annual subsidy equivalent to $1,500 for each of her parents and $1,200 for a grandmother who lives with them.

“Jiali’s mother, Du Jinping, 45, said the family would live in the new village in the winter, but return to Swan Lake in the summer. The family charges each tourist $4.50 to visit Swan Lake. Visitors also rent camels and dune buggies. And they can pay to eat in the round Mongolian tents, called gers. But the oasis, which is the main attraction, is shrinking. Many of the oases in the Tengger are drying up. Local governments in desert regions began relocating people away from the encroaching sands decades ago. But China’s densely populated areas are pushing toward the deserts, as the deserts grow toward the cities. Storms of wind-driven sand have become increasingly frequent and intense, reaching Beijing and other large cities. “We dread the sandstorms,” Ms. Du said.

Farming is becoming more difficult. Huang Chunmei, who grew up in the town of Tonggunao’er and now farms there, said the water table was two meters, or about six feet, below ground during her childhood, and “now, you have to dig four or five meters.” Ms. Huang planted more than 200 trees on her own last spring, in the hope that they would help block sandstorms and hold back the sand. Ms. Huang, 38, grows corn and tomatoes, some in greenhouse structures. “The soil is not as soft or good as it was before,” she said. “We use more fertilizer now.” Ms. Huang and her husband have sent their 14-year-old daughter to a boarding school in a nearby city. “I don’t want my girl to return,” she said. The sand and wind make life tough here.” We’ll see what she wants to do when she finishes school.”

“About 17 percent of the population in Alxa League are ethnic Mongolians, whose lives and livelihoods have long been tied to the herding the government is trying to halt. Mengkebuyin, 42, and his wife, Mandula, 41, grow corn and sunflowers, but their 200 sheep provide most of their income: They sell the meat to a hotel restaurant in a nearby city. The sheep graze in the desert, where grass is growing scarce. They roam by his old family home, near the shores of a lake that dried up years ago. Mengkebuyin and his wife maintain the old home but do not stay for long periods. They have moved to a village five miles away. Mengkebuyin uses a motorcycle and a desert buggy to drive the sheep to graze. He would like to move to better pasture, but the government will not allow it. He herds the sheep toward the old family home, where he can give the animals water. Mengkebuyin and Mandula have decided that they want their 16-year-old daughter to live and work in a city. Four generations of Mengkebuyin’s family lived by the lake in a thriving community. But gradually, everyone left.

Image Sources: 1, 2) Nature Products; 3) ESWN, Environmental News; 4) IIASA; 5, 6) FAO; 7) Julie Chao ; 8) Landsberger Posters 9) UNCCD

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2022