COMBATING DESERTIFICATION IN CHINA

To combat desertification, the government has encouraged the planting of drought-resistant trees in erosion-prone areas and helped people to obtain technology that helps them collect and store rainwater. In some places farmers are paid to plant trees rather than raise crops. Pines and poplars provide shields from encroaching dunes. On the Loess Plateau erosion has been reduced, with funding from the World Bank, by terracing the landscape.

The Institute of Desert Research in Shapotou, a town on the Yellow River, is facility that is devoted to solving problems related to desertification. Spread out over one square mile, it employs 19 full time researchers who conduct experiments with drought-resistant crops; desert agriculture techniques; the use of plants, shrubs and grasses to stabilize dunes; petroleum-based dune stabilizing sprays; and Israeli-style drip irrigation.

Chinese leaders such as President Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping have travelled to Ningxia to hail it "model" projects there. A model farmer there has been elevated the ranks of heroes like Yang Liwei, the first Chinese man in space, and Yuan Longping, inventor of a hybrid rice. The "warrior of the sands", as he is known, was even one of the torch carriers at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Beijing insists its efforts are paying off, and says that China’s deserts are shrinking at a rate of 1,200 square kilometers a years, compared to increasing a rate of 3,500 square kilometers in the late 1990s. No everyone accepts these figures. Some towns in Inner Mongolia have built clay walls to keep sand and dust out. But even that hasn’t proved to enough as sand has come in and engulfed houses, marginalized agriculture and forced people to move.

Nonetheless, China's limited success in the fight against desertification has become a global reference point, and foreign experts and political leaders are flocking to Baijitan to see the project. Hussein Hawamdeh of the University of Jordan is one. He told AFP in Ningxia that China's experience had been useful in his country's Badia region, a major farming area that is under threat from rapid desertification.

In places where overgrazing is a problem fences have been put up and herders have been given plots of land to encourage them to take good care of the land. To reduce the number of animals the government is encouraging herders to cut the size of their flocks by 40 percent, relocate and stall-feed their animals. But herders are not so keen on these ideas. Animals have traditionally been a source of wealth and a kind of insurance for hard times.

See Separate Articles DEFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DESERTIFICATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TORNADOES, LIGHTNING AND SAND, DUST, AND SNOW STORMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DROUGHTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com RAINMAKING AND MAN-MADE WEATHER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Aridity Trend in Northern China” by Congbin Fu and Huiting Mao Amazon.com; “China's Water Crisis” by Jun Ma , Nancy Yang Liu, et al. (2004) Amazon.com; “China's Water Resources Management: A Long March to Sustainability” by Seungho Lee (2021) Amazon.com; “Water Resources Management of the People’s Republic of China: Framework, Reform and Implementation” by Dajun Shen Amazon.com “Managing Water on China's Farms: Institutions, Policies and the Transformation of Irrigation under Scarcity” by Jinxia Wang, Qiuqiong Huang, et al. (2016) Amazon.com; Environmental Issues: “China's Environmental Challenges” by Judith Shapiro Amazon.com; “Environmental Issues in China Today: A View from Japan”by Hidefumi Imura Amazon.com; “China’s Engine of Environmental Collapse” by Richard Smith Amazon.com; “The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China's Future” by Elizabeth C. Economy Amazon.com; “The Environmental Issues in China: A Primer & Reference Source” by Min Wei and Timothy Fielding Amazon.com History: “China: Its Environment and History” by Robert B. Marks Amazon.com; “The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China” by Mark Elvin Amazon.com; “Mao's War Against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China” by Judith Shapiro Amazon.com

Great Green Wall

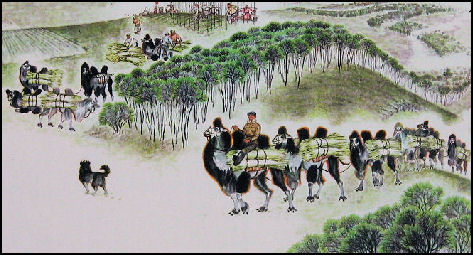

A 4,500 kilometers long Green Belt — sometimes called the Great Green Wall — has been created in northern China with 35 billion trees.The planting in the north has been done in one-mile wide strips and the survival rate of the millions of acres reforested has been 70 percent.

Described as the world's most ambitious reforestation project, the Chinese planted a line of trees and shrubs, paralleling the Great Wall of China, to protect farmland in northern China from Gobi Desert sand blown by the fierce Mongolian winds. Stretching from Xinjiang to Heolongjang,

David Stanway of Reuters wrote: “Tree-planting has been at the heart of China's environmental efforts for decades as the country seeks to turn barren deserts and marshes near its borders into farmland and screen the capital Beijing from sands blowing in from the Gobi, a 500,000 square-mile expanse stretching from Mongolia to northwest China, which would coat Tiananmen Square in dust nearly every spring. Their painstaking work to rehabilitate marginal land has been promoted as an inspiration for the rest of the country, and they are the subject of government propaganda posters celebrating their role in holding back the sand. [Source: David Stanway, Reuters, June 3, 2021]

“Over the last four decades, the Three-North Shelter Forest Programme, a tree-planting scheme known colloquially as the "Great Green Wall", has helped raise total forest coverage to nearly a quarter of China's total area, up from less than 10 percent in 1949. In the remote northwest, though, tree planting is not merely about meeting state reforestation targets or protecting Beijing. When it comes to making a living from the most marginal farmland, every tree, bush and blade of grass counts — especially as climate change drives up temperatures and puts water supplies under further pressure. "The more the forest expands, the more it eats into the sands, the better it is for us," one farmer told Reuters.

The man-made forest was made in part to reduce dust storms in northern China and recently has been tasked with taming smog. The strategy works in some cases. But low-lying foliage does not slow down the movement of cold air, which travels at a height of more than 1.5 kilometers above ground and this cold air is associated both with dust storms and the movement of smog from downwind factories to Beijing and other cities.

Battling Desertification in Ningxia with Straw Squares

Using a technique introduced by the Soviets in 1962, the Chinese have made progress slowing down sand dune migration by putting plants inside "small checkerboards" made of straw bales to protect the plants long enough for them to take hold permanently while stabilizing the dunes and stopping sand from blowing. Arranged roughly in one-meter square checkerboards, the grids are pressed into the sand so that the stalks stand four to six inches above the ground. This creates enough of a windbreak to slow surface sand movement so the plants can establish themselves The technique was devised to keep sand from blowing across railroad tracks — at one time a serious problem that blocked tracks and slowed commerce and passenger service.

AFP reported: Wang Youde digs into a sand dune to build small square ramparts out of straw in which plants designed to check the desert's relentless advance will take root, Wang, 57, is the head of the Baijitan collective farm in Ningxia, a remote region of northern China that is regularly battered by ferocious sandstorms and whose capital is under threat from the expanding Maowusu desert. Ningxia, next to the vast Gobi desert, is often called the "thirsty country". [Source: AFP, November 1, 2011]

As a youth, Wang witnessed the ravages of desertification, from lost cultures to families forced to flee and houses buried — events that have affected him deeply. "At the beginning, the situation we faced was very difficult. We did not have the money to fight the sands. We even had to go to the town to find financing," says Wang, whose face is deeply tanned after decades of working in the open ai. Along with his relatives — who, like him, are members of China's Hui Muslim minority — Wang launched himself into a Sisyphean battle to try to "fix" the dunes of the Maowusu. His method of using straw to fence off plants and protect them is simple, but labour intensive. The Baijitan cooperative employs around 450 workers who live on site, two thirds of them Muslims.

"Each worker has an annual target of digging 10,000 holes, sowing 10,000 plants and makes 10,000 yuan ($1,567)," says Wang. Using water taken from the region's very deep water table, they are achieving miracles. The director shows off the fruits of his project — orchards, planted in a sandy valley, that produce juicy apples. All around, the sand dunes are chequered with squares of green as bit by bit the vegetation takes over. Wang says the planting has slowed the winds carrying the sand by 50 percent.

The Baijitan reserve covers 1,480,000 mu — a Chinese measure equivalent to around 100,000 hectares. It contains a "green belt" 10 kilometres (six miles) wide and 42 kilometres long intended to contain the advance of the dunes. The land belongs to the state, but the government only puts up around one fifth of the financing with the rest coming from the sale of farm produce, including apples and peaches.

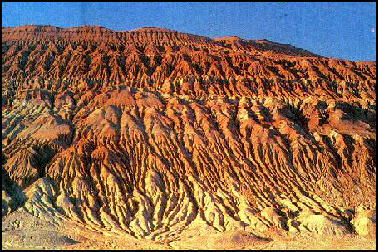

Tree Planting and Landscape Restoration on the Loess Plateau

Charles C. Mann wrote in National Geographic, “In response, the People's Republic initiated plans to halt deforestation. In 1981 Beijing ordered every able-bodied citizen older than 11 to "plant three to five trees per year" wherever possible. Beijing also initiated what may still be the world's biggest ecological program, the Three Norths project: a 2,800-mile band of trees running like a vast screen across China's north, northeast, and northwest, including the frontier of the Loess Plateau. Scheduled to be complete in 2050, this Green Wall of China will, in theory, slow down the winds that drive desertification and dust storms.” [Source: Charles C. Mann, National Geographic, September 2008]

“Despite their ambitious scope, these efforts did not directly address the soil degradation that was the legacy of Dazhai. Confronting that head-on was politically difficult: It had to be done without admitting Mao's mistakes. (When I asked local officials and scientists if the "Great Helmsman" had erred, they changed the subject.) Only in the past decade did Beijing chart a new course: replacing the Dazhai Way with what might be called the Gaoxigou Way.”

Paul Mozur wrote in the New York Times, In 2005, “the Chinese government, in cooperation with the World Bank, completed the world’s largest watershed restoration on the upper banks of the Yellow River. Woefully under-publicized, the $500 million enterprise transformed an area of 35,000 square kilometers on the Loess Plateau — roughly the area of Belgium — from dusty wasteland to a verdant agricultural center.” [Source: Paul Mozur, New York Times, December 10, 2009]

“The result of careful terracing, replanting of native vegetation and restrictions on grazing, the rejuvenated land now supports a thriving local agricultural economy. Even better, the new vegetation reduces flooding and dust storms by anchoring the region’s soil and is becoming a large carbon sink.

A 2009 film directed and written by John Liu, the founder of the Environmental Education Media Project and a veteran eco-film director, tell the story of the Loess Plateau. The documentary, “Hope in a Changing Climate”, takes the story of the Loess Plateau as its lead, but quickly moves to Rwanda and Ethiopia where similar successes have come from a process known as forest landscape restoration, which hold great promise globally for combating deforestation, desertification and global warming.

Landscape restoration is a slow, complex and painstaking process. Mozur wrote in the New York Times,”It can take decades for vegetation to fully return, and strict attention must be paid to mundane matters like grazing and over-planting.... Because ecosystems vary based on geography, and lasting success depends on the support of local residents, the process is pesteringly cross-disciplinary. Any forest landscape restoration project requires the know-how of engineers, ecologists and soil scientists, plus an understanding of local economics and politics. In the Loess Plateau locals built and must maintain the terraces that have brought about their ecosystem’s incredible recovery.”

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, “There was one truly significant sign of greening long under way in the region: a massive tree-planting campaign designed to hold the fragile soil in place. Flatbed trucks packed with seedlings were the second most common sight along area roads (outnumbered ten to one, it seemed, by trucks carrying coal from the mines). Ding estimated that he'd planted 100,000 trees with his own hands. "It used to be very dusty here, with lots of sandstorms," he said. "But we had 312 blue sky days last year, and every year there are more." [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

Overgrazing by cashmere goats

Planting Bushes and Trees in Gansu

Reporting from Wuwei in Gansu Province, China David Stanway of Reuters wrote: After a hard morning planting fresh shoots in the dunes on the edge of the Gobi Desert, 78-year-old farmer Wang Tianchang retrieves a three-stringed lute from his shed, sits down beneath the fiery midday, and starts to play. "If you want to fight the desert, there's no need to be afraid," sings Wang, a veteran of China's decades-long state campaign to "open up the wilderness", as he strums the instrument, known as the sanxian. Now a local institution in northwest China's Gansu province, Wang and his family lead busloads of young volunteers from the provincial capital of Lanzhou into the desert each year to plant and irrigate new trees and bushes. [Source: David Stanway, Reuters, June 3, 2021]

In a battered jeep loaded with a water tank and flying a large Chinese national flag, the Wang family have been planting the spindly "huabang" in the rolling dunes. The flowering bush known as the sweetvetch has an 80 percent success rate even in harsh desert conditions and has become a key part of efforts to "hold down the sand", a term used locally for planting bushes and grasses in even squares across the desert slopes to stop sand drifting into nearby farmland.

“The Wangs have been fighting desertification since they settled on barren land near the village of Hongshui in Wuwei, a city in Gansu close to the border with Inner Mongolia, in 1980. Their home is now surrounded by patches of rhubarb and rows of pines and blue spruces. Twenty bleating goats are locked in a wooden paddock nearby to stop them devouring the precious vegetation. The family's four acres of farmland are protected on one side by a forest planted about a decade ago, and on the other by a long sandy cliff.

“Trees have become a major part of the local economy. Hongshui is dominated by a large state-owned commercial forest estate called Toudunying. "After 1999, when the tree-planting sped up, things got much better," Wang Yinji said, referring to the state-led reforestation initiative. "Our corn grew taller. The sand that used to blow in from the east and northeast was stopped."

Gaoxigou Way to Restore the Loess Plateau

Charles C. Mann wrote in National Geographic, “Gaoxigou (Gaoxi Gully) is west of Dazhai, on the other side of the Yellow River. Its 522 inhabitants live in yaodong — caves dug like martin nests into the sharp pitches around the village. Beginning in 1953, farmers marched out from Gaoxigou and with heroic effort terraced not mere hillsides but entire mountains, slicing them one after another into hundred-tier wedding cakes iced with fields of millet and sorghum and corn. In a pattern that would become all too familiar, yields went up until sun and rain baked and blasted the soil in the bare terraces. To catch eroding loess, the village built earthen dams across gullies, intending to create new fields as they filled up with silt. But with little vegetation to slow the water, "every rainy season the dams busted," says Fu Mingxing, the regional head of education. Ultimately, he says, villagers realized that "they had to protect the ecosystem, which means the soil." [Source: Charles C. Mann, National Geographic, September 2008]

“Today many of the terraces Gaoxigou laboriously hacked out of the loess are reverting to nature. In what locals call the "three-three" system, farmers replanted one-third of their land — the steepest, most erosion-prone slopes — with grass and trees, natural barriers to erosion. They covered another third of the land with harvestable orchards. The final third, mainly plots on the gully floor that have been enriched by earlier erosion, was cropped intensively. By concentrating their limited supplies of fertilizer on that land, farmers were able to raise yields enough to make up for the land they sacrificed, says Jiang Liangbiao, village head of Gaoxigou.”

“In 1999 Beijing announced it would deploy a Gaoxigou Way across the Loess Plateau. The Sloping Land Conversion Program — known as "grain-for-green" — directs farmers to convert most of their steep fields back to grassland, orchard, or forest, compensating them with an annual delivery of grain and a small cash payment for up to eight years. By 2010 grain-for-green could cover more than 82,000 square miles, much of it on the Loess Plateau.

“But the grand schemes proclaimed in faraway Beijing are hard to translate to places like Zuitou. Provincial, county, and village officials are rewarded if they plant the number of trees envisioned in the plan, regardless of whether they have chosen tree species suited to local conditions (or listened to scientists who say that trees are not appropriate for grasslands to begin with). Farmers who reap no benefit from their work have little incentive to take care of the trees they are forced to plant. I saw the entirely predictable result on the back roads two hours north of Gaoxigou: fields of dead trees, planted in small pits shaped like fish scales, lined the roads for miles. "Every year we plant trees," the farmers say, "but no trees survive."

“Some farmers in the Loess Plateau complained that the almonds they had been told to plant were now swamping the market. Others grumbled that Beijing's fine plan was being hijacked by local officials who didn't pay farmers their subsidies. Still others didn't know why they were being asked to stop growing millet, or even what the term "erosion" meant. Despite all the injunctions from Beijing, many if not most farmers were continuing to plant on steep slopes. After talking to Zhang Liubao in Zuitou, I watched one of his neighbors pulling turnips from a field so steep that he could barely stand on it. Every time he yanked out a plant, a little wave of soil rolled downhill past his feet.”

Planting of the Great Green Wall

Is Tree Planting the Best Strategy to Halt Desertification

David Stanway of Reuters wrote: “This competition for land has been reinforced by China's reliance on government-backed industrial-scale plantatio "There's been relatively low survival of trees in some regions, and discussions about the depletion of underground water tables," said Hua Fangyuan, a conservation biologist who focuses on forests at China's Peking University. [Source: David Stanway, Reuters, June 3, 2021]

“One such state-backed forest farm designed to repair the region's overworked ecosystem is the 4,200-acre Yangguan project, on the outskirts of the city of Dunhuang, which has proven controversial. Leaseholders eager to plant lucrative but water-intensive grapes levelled large sections of forest in 2017. In March 2021, a government investigation team found Yangguan had violated regulations by allowing vineyards to be planted in protected forest. Villagers were also accused of illegally felling trees, and authorities were ordered to reclaim the illegally occupied land.

“Officials on the estate said hundreds of staff from government agencies in Dunhuang would arrive soon with the aim of planting 31,000 trees on 93 acres of land in just four days. Gradually the surviving vineyards would be replaced with trees, a manager said, a move that would affect hundreds of farmers. "The government and the farmers should work together to find a way to make money and ensure the water levels are sustainable at the same time," said said Ma Lichao, China country director for the Forest Stewardship Council, a non-profit organisation promoting sustainable forest management.

Yongning Green Migration Scheme

Sebastien Blanc of AFP wrote: On a dry plain in China's remote northern Ningxia region, thousands of neatly aligned, identical brick houses have sprung up from the dusty soil. This is the Yongning Green Migration Scheme, where 3,000 two-room houses are being built to accommodate 17,800 villagers from the poorer, mountainous south of the region. [Source: Sebastien Blanc, AFP October 13, 2011]

Bu Xing'ai, director of external affairs for Ningxia, said authorities planned to move 350,000 people within the autonomous region over the next five years as he showed off the project to journalists on a recent visit. China's breakneck economic growth has been accompanied by huge population movements, as exemplified by Ningxia, where new towns have been quickly built, sometimes at the heart of semi-arid zones.

For the government, planned migration is a way of channelling the inevitable rural exodus and redistributing the labour supply to suit the country's needs. Authorities in Ningxia say those who move under the scheme will have a better quality of life than they do at present.A cement factory with the capacity to produce 4,500 tonnes of cement a day is being built to provide employment for the migrants. "Once they are here they will find roads, electricity, water, they will be able to find work at the factory and their children will be able to go to school," said Wu Guangning, deputy director for development and reform in Ningxia's Yongning county.

Many of the intended residents are Hui, a Muslim minority that has lived in the autonomous region of Ningxia for centuries. The local climate is dry, but the authorities have planned an irrigation scheme that would allow residents to grow grapes, mushrooms and goji berries — a highly nutritious fruit that is popular in the area.

It is not entirely clear why the scheme has been labelled "green". The roofs of the houses are to be fitted with solar panels, but they are not yet visible. Each house will cost 40,000 yuan ($6,275), but of that, the local government provided 30,000 yuan, said Wu.

Asked about the practicalities of getting mountain people to move to the desert, Wu said they were being encouraged to come and see the new settlement and decide whether they are "satisfied" with it. "They are currently living in very difficult conditions," he added.

With no one yet living in the new houses, and their proposed occupants living many hours' drive away, it was not clear how their satisfaction with the new housing might be gauged.So, the organisers of the trip took the journalists by bus to see a migrant who had agreed to be interviewed in his tiny home, where baskets of fruit had been laid out.Ma Guowen was dressed in a Muslim skull-cap and wearing his best jacket for the occasion. But the farm worker's comments on the benefits of the government rehousing scheme seem a little too pat to be convincing.

Image Sources: 1, 2) Nature Products; 3) ESWN, Environmental News; 4) IIASA; 5, 6) FAO; 7) Julie Chao ; 8) Landsberger Posters 9) UNCCD

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2022