FLYING FOXES

Flying foxes are the world’s largest bats. They are distinguished from other kinds of bats in that, for the most part, they use their eyes not echolocation to locate objects. Flying foxes get their names from their foxy faces. Some neurological and morphological studies have shown that they may not be that distantly related from primates.

Flying foxes are also called fruit bats and belong to the groupings of Old World Bat and Megabats, of which there are almost 200 species scattered across southern Asia, and the islands off southeast Africa and the South Pacific — but not in the Americas and Europe. They are most common in tropical Asia, Madagascar, Australia and the South Pacific islands. Southeast Asia is home to many species of flying fox. The Indian flying fox is the world’s largest bat. It has a body the size of a house cat and wingspan up to five feet.

Flowering plants are essential to the diet of flying foxes, who mostly use woodlands or orchards for food. Canopy emergent fruiting trees, such as fig and baobab trees, are frequently used as a food source. Many species are found in coastal areas and drink salt water in order to supplement nutrients lacking in their diet. A few species are migratory, [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Flying foxes often prefer to roost in narrow strips of fragmented forest rather than in large primary forest. David Attenborough wrote: “The bigger species are so large that in order not to lose too much height in take-off, they beat their wings two or three times to lift their bodies from the vertical to the horizontal and then unlatch their feet.” Flying foxes are thought to have made their way to Madagascar by island hopping.

Flying foxes play and important role in the pollination and seed dispersal of a wide range of plants. On islands in the south Pacific, they are the principle pollinators and dispersers of plants. Many plants have adaptations specifically for seed dispersal and pollination by bats, such as fruiting or flowering at the ends of branches and at bat accessible locations in the canopy. /=\

RELATED ARTICLES:

WORLD’S BIGGEST BATS — LARGE, INDIAN AND GREAT FLYING FOXES — AND THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

FLYING FOXES OF THE ISLANDS OF INDONESIA AND THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

BATS AND FLYING FOXES IN AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa. factsanddetails.com

GRAY-HEADED FLYING FOXES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa. factsanddetails.com

BATS, CHARACTERISTICS, FLIGHT, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ;

BAT SENSES AND ECHOLOCATION factsanddetails.com

BATS AND HUMANS: GOOD THINGS, DISEASE, RABIES AND DEATHS factsanddetails.com

KINDS OF BATS: SMALLEST, BIGGEST, VAMPIRE BATS factsanddetails.com

HORSESHOE BATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND COVID-19 factsanddetails.com

ASIAN FALSE VAMPIRE BATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BUMBLEBEE BATS (WORLD'S SMALLEST MAMMALS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Animals: Bat Conservation Trust bats.org.uk ; Bat Conservation International batcon.org ; Merlin Tuttle is the founder and president of Bat Conservation International; Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Flying Fox and Megabat Taxonomy and Fossil History

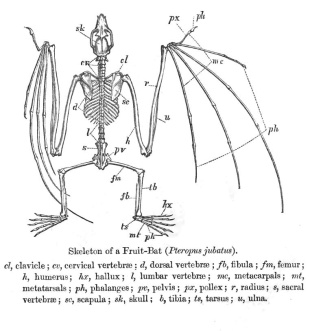

Flying foxes belong to the genus Pteropus, which is part of the suborder Yinpterochiroptera and families of Megabats and Pteropodidae of the order Chiroptera (bats). Internal divisions of Pteropodidae have varied since subfamilies were first proposed in 1917. From three subfamilies in the 1917 classification, six are now recognized, along with various tribes. There are at least 60 extant species in the genus. [Source: Wikipedia]

Pteropus is a genus of megabats. Megabats are also called fruit bats, Old World fruit bats, or — especially the genera Acerodon and Pteropus — flying foxes. They are the only member of the superfamily Pteropodoidea, which is one of two superfamilies in the suborder Yinpterochiroptera. As of 2018, 197 species of megabat had been described.

The leading theory of the evolution of megabats has been determined primarily by genetic data, as the fossil record for this family is the most fragmented of all bats. They likely evolved in Australasia, with the common ancestor of all living pteropodids existing approximately 31 million years ago. Many of their lineages probably originated in Melanesia, then dispersed over time to mainland Asia, the Mediterranean, and Africa. Today, they are found in tropical and subtropical areas of Eurasia, Africa, and Oceania.

The fossil record for pteropodid bats is the most incomplete of any bat family. Although the poor skeletal record of Chiroptera is probably from how fragile bat skeletons are, Pteropodidae still have the most incomplete despite generally having the biggest and most sturdy skeletons. It is also surprising that Pteropodidae are the least represented because they were the first major group to diverge.

Flying Fox Characteristics

Flying foxes are dark grey, black or brown in color with a yellow or tawny mantle. Their muzzle is long and slender like a fox’s; the hair on their bodies may be up to a foot long; and their fingers may be as long as their arms. Tendons in their feet allow them to hang upside down without effort. They need muscles to let go. They are quite agile climbing through trees but they can’t walk or sit. Their index finger is free from the membrane and is used as a hook when clambers through the branches. Flying foxes maintain body temperatures between 33̊ and 37̊C (91.4̊to 98.6̊F , but must be almost constantly active to do so.

Flying fox species vary in body weight, ranging from 0.12 to 1.6 kilograms (0.26–3.53 pounds). Among all species, males are usually larger than females. The large flying fox has the longest forearm length and reported wingspan of any bat species. Its wingspan is up to 1.5 meters (4 feet 11 inches), and it can weigh up to 1.1 kilogram (2½ pounds). Some bat species exceed it in weight. The Indian and great flying foxes are heavier, at 1.6 and 1.45 kilograms respectively. Most flying fox species are considerably smaller and generally weigh less than 600 grams (21 ounces). [Source: Wikipedia]

The fur is long and silky with a dense underfur. In many species, individuals have a "mantle" of contrasting fur color on the back of their head, the shoulders, and the upper back. They lack tails. As the common name "flying fox" suggests, their heads resemble that of a small fox because of their small ears and large eyes. Females have one pair of mammae located in the chest region. Their ears are long and pointed at the tip and lack tragi, the outer margin of each ear forming an unbroken ring. The toes have sharp, curved claws. While microbats only have a claw on each thumb of their forelimbs, flying foxes additionally have a claw on each index finger.

Despite their size variations flaying foxes share many characteristics: A relatively long rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth), which is pronounced in nectarivores, large eyes, and simple external ears, which them their fox-like appearance. According to Animal Diversity Web: The genera Nyctimene and Paranyctimene are exceptions in that they contain tubular nostrils that project from the upper surface of the snout. The tongue is highly protrusible in nectar feeding bats and often complex with terminal papillae. The chest is robust, comprised of the down-thrusting pectoralis and serratus muscles. The articulating regions of the humerus never come into contact with the scapula, which differs from a locking mechanism that occurs in the shoulder joint of other bat groups. The second digit is relatively independent from the third digit and contains a vestigial claw that adorns the leading edge of the wing. [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Modifications for hanging include a relocation of the hip socket. The acetabulum is shifted upward and dorsally, and articulates with a large headed femur for a wider range of motion. In contrast to most other mammal orders, the legs cannot be positioned in a straight line under the body. In conjunction with large claws on their feet, pteropodids use a tendon-ratchet system that allows them to hang without prolonged muscular contraction. The legs manipulate a primitive uropatagium (membrane between the forelimbs and hindlimbs used for gliding) during flight. /=\

Flying Fox Senses

Flying foxes do not echolocate, and therefore rely on sight to navigate. Their eyes are relatively large and positioned on the front of their heads, giving them binocular vision. Like most mammals, though not primates, they are dichromatic. They have both rods and cones; they have "blue" cones that detect short-wavelength light and "green" cones that detect medium-to-long-wavelengths. The rods greatly outnumber the cones, however, as cones comprise only 0.5 percent of photoreceptors. Flying foxes are adapted to seeing in low-light conditions. [Source: Wikipedia]

Flying foxes also rely heavily on their sense of smell. They have large olfactory bulbs to process scents. They use scent to locate food, for mothers to locate their pups, and for mates to locate each other. Males have enlarged androgen-sensitive sebaceous glands on their shoulders that they use for scent-marking their territories, particularly during the mating season. The secretions of these glands vary by species—of the 65 chemical compounds identified from the glands of four species, no compound was found in all species. Males also engage in "urine washing", meaning that they coat themselves in their own urine.

Flying foxes sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. Intraspecific communication is often vocal. Among some species such as the grey-headed flying fox vocal signaling may be associated with specific motor activities which enhance the meaning of the vocal signal. In species such as the Straw-coloured fruit bat, sexually dimorphic sebaceous glands which are larger in males may provide olfactory behavioral cues. [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Flying Fox Behavior

Flying foxes are arboreal (live mainly in trees), fly, nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), sedentary (remain in the same area), have daily torpor (a period of reduced activity, sometimes accompanied by a reduction in the metabolic rate, especially among animals with highmetabolic rates), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups) and colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other). [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Pteropodids can functionally be divided into two groups based on size. Smaller pteropodids that tend to have shorter, deeper wings which allow for more maneuverable flight under the canopy; and Larger pteropodids that have longer, narrower wings which allow for efficient long distant flight. Pteropodid species display varying degrees of coloniality. This range is broad, from solitary species to those that roost in groups of up to 200,000 individuals. Roost size may also vary seasonally within a species, possibly due to a depletion of local food sources. Some species commonly roost in mixed groups with other species. Roost selection by pteropodids is poorly understood. Pteropodids roost in a wide range of habitats, from cultivated kapok plantations to rainforests and mangroves. Some species are associated with particular types of plants. Pteropodids can show long term fidelity to roost sites when the sites are undisturbed. Some species of Pteropus in Australia have been recorded using the same roost for over 80 years. [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

During the day, many flying foxes sleep upside down in huge groups in trees with their wings folded around them. Several hundred may occupy a single tree and colonies numbering in the thousands often occupy several trees. In the early 20th century there were reports of flying fox “camps” over 4½ miles long and a mile wide, with millions of animals. When they took off they blackened the sky.

Fruit bats roost in the open unlike other bats which sleep in caves. When they urinate the urine trick;es down their wings and to whatever is below — perhaps another bat. In Australia more than a million of them sill gather in the same place, creating a noisy, smelly ruckus. Usually one or two of flying foxes stay awake to keep an eye out for hawks or snakes — their natural predators. When these bats fly off it alerts the others of trouble. Each bat needs its own space. Individuals don’t like to touch other bats. The squawking sound that fruit bat make is often the sound of bats bickering over space as they shift around. At dusk the bats leave their roosts. They can take off en mass or fly one after the other.

Fruits bats urinate when frightened. After disturbing a group roosting in a tree National Geographic photographer Carry Wolinsky said, "I feel a warm rain, smelling oddly like the New York City subway." Flying foxes also have a reputation for shitting partially digested fruit all over people who disturb them.

Flying Fox Feeding

Flying foxes are frugivorous (fruit eating) and nectarivorous (nectar eating). They feed primarily on rain forest fruits, figs, nectar and blossoms and, to a lesser degree, tropical fruits like bananas, plantains, breadfruit, and mangoes. Some species also eat flowers of the plants they visit. Many species rely heavily on figs. Others rely on broad array of resources. Some fruiting plants rely on bats — whose digestive system rapidly processes food without disturbing the seeds — to distribute their seeds through the bat's fecal matter. They also spread pollen like birds and bees in flowering trees. Their long tongues are designed for lapping up nectar. Pollen sticks to their hairy bodies.

Bigger flying foxes rely heavily on canopy resources while and smaller species that can penetrate the supper canopy and obtain understory resources better. Some larger species can use the claws on their thumbs and second digits to climb into the understory and seek out fruit that they can’t reach by flight. [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The nomadic wanderings of flying foxes is often determined by their search for food. They travel far and wide to find trees that are fruiting or producing nectar-rich blossoms. It is not unusual for a bat to put in 60 miles a night flying from tree to tree in search of food. They suffer greatly when normal fruiting and blossoming patterns are disrupted by droughts, fires or flood. That is often when they are mostly likely to descend on orchards.

David Attenborough wrote: “Some fruit bats feed almost entirely on fruit nectar. Some species of tree rely on them to carry pollen from flower to flower, where they feed. Such trees — among them certain mangroves, cacti and eucalyptus — produce flowers that only open at night and are white in color and as a consequence are more easily seen by the bats in the night. Many of these blooms stand free of twigs and leaves so that the bats that feed off them don’t entangle their wings. Others hang from long stems and their flowers produces nectar in great quantities but also make a very strong fragrance that the bats are able to detect from long distances.”

“Flying foxes are only incidentally nectar drinkers. Their bulk of their diet is fruit. They may travel 20 miles or more to find trees that are beginning to ripen. Many fruits are so full of water and contain so little nutrition an individual bat can consume its own weight in them in a single day, spitting out the indigestible pulp, swallowing the juice and quickly urinating unwanted liquid. But on the way back to the roost, they may defecate seeds. Fruit bats can devastate a fruit farmer’s entire crop in a day. But they are nevertheless, prime agents in maintainng the fertility of the forest.”

Flying Fox Mating

Mating behavior in flying foxes is highly variable, and much is unknown. The males of one genus (Hypsignathus) set up lekking territories twice a year and draw in females with unique vocalizations and wing-flapping displays. While most bats have one reproduction event per year, many flying foxes are polyestrous, with two seasonal cycles corresponding to the annual wet and dry seasons. Many species form harems consisting of one dominant male and up to 37 females, while bachelor males roost separately. [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Females have an estrous cycle, which is similar to the menstrual cycle of human females. They may engage in delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months). Usually one young is born per pregnancy, but twins are not uncommon. Females are primarily responsible for rearing the young. Nursing lasts anywhere from seven weeks to four months, and the mother may care for her young slightly longer.

Some species of flying foxes are called epauletted bats (genus Epomophorus) because males have large retractable patches of fur that sprout out from pouches in their shoulders during their courtship displays. Male epauletted fruit bats often display their concealed epaulets while emitting courting calls to attract females. Female epauletted bats "give birth to a single baby once or twice a year. In some areas these births are closely synchronized with the long and short rains, but in other, births seem to occur throughout the year.

electrocuted flying fox

During the mating season males of some species of epauletted bat hang out near street lights flashing the patches of normally hidden fur, secreting attractive odors, singing and honking rhythmically from inflatable sacs in their cheeks and beating their half-closed wings to attract females that apparently need the light to see the males. When rivals land on nearby lamppost the males try to outdo each other by increasing the rate of their calls. The females arrive about 11:00pm and hover about a yard away from the males, checking one out before moving on to the next. When the female chooses the male she wants, her suitor wraps his wings around her so nobody can see.

Pregnant females usually leave social roosts to form nursery groups with other pregnant females. Females in nursery roosts form their own social network and take care of each other through mutual grooming. At dusk mothers carry their babies with them when they fly out to feed, even though, amazingly, some young are two thirds the weight of their mothers and quite capable of flying on their own. The young bat rides clinging to its mother's breast. At feeding sites a baby may fly alongside its mother and even compete with her for food. That same baby may then suckle as it is carried home." During the day nursing young are cradled beneath their mothers' wings, invisible except when they occasionally peek out.

Females must contribute close to all of the calcium that is required to the developing skeletal system of the offspring. As a consequence, females often suffer from osteoporosis. Females with osteoporosis have a greater chance of breaking bones necessary for flight. Without the ability to fly, there is a high probability that females with broken limbs will die from starvation. [Source: Jeremie Marko, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Flying Fox and Humans

Flying foxes have traditionally been regarded as pests because they make a lot of noise, contaminate water supplies, sometime raid orchards, and generally make a nuisance of themselves. In some places a bounty was placed on killing them. In turn flying foxes often squeal with displeasure when humans are present.

Many crop species are attractive food sources for flying foxes. Because cultivars are often developed from wild species, commercial crops have the same characteristics that wild plants evolved to attract bats and other animals to their fruit. Fruit growers have experimented with visual, audio, and olfactory deterrents as well as electric wire to keep flying foxes from eating their crops. [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

But their reputation appears to have been greatly exaggerated. In Australia, in the 1920s, a British biologist was brought in to “discover some whole sale method of destruction which would once and for all relieve the growers of the onus of dealing with the pest.” After his study, the biologist concluded: “The assumptions that the flying fox is a menace to the commercial fruit industry...is quite definitely false...The lose to the commercial fruit crop...is so negligible as to be almost trifling.” Outside of Australia studies have shown that monkeys are often the culprits not bats. Fruit-eating bats only eaten ripened fruit but monkeys will eat unripened fruit.

Flying foxes have been blamed for spreading diseases such as lyssavirus, a close relative of rabies, the Nipah virus, Menangle virus, the Hedra virus and Ebola and other viruses in the family Paramyxoviridae. After World War II there were high incidences of dementia among people who lived on Guam and ate large numbers of flying foxes. Later neurologist Oliver Sacks and ethnobiologist Paul Allen Cox examined flying foxes preserved in a museum and found there bodies contained large amounts of neurotoxins absorbed from feeding on cyad seeds. Apparently the animals were unaffected by the toxin but they absorbed enough of them to pass them on to humans who ate them, causing Alzheimer-like diseases.

Threats to Flying Fox

Some flying foxes and fruit bats are threatened or endangered. Deforestation and loss of habitat has reduced their normal feeding areas and made it more likely for them to raid crops. Large flying foxes are sometimes hunted for their meat, which is considered a delicacy in some areas, and they are easy targets because they often roost in large groups on the branches of large trees or well light caves. Both subsistence and commercial hunting have been reported. Consumer demand on the island of Guam has been so great that it has resulted in the extinction of at least one species in the Pacific region. [Source: Kenneth Cody Luzynski; Emily Margaret Sluzas; Megan Marie Wallen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In Asia and Australia, deforestation is the most important contributor to flying fox population decline. Some species are vulnerable to typhoons and hurricanes which may destroy roosting habitat on islands. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species lists five species as recently extinct, 10 species as critically endangered, 19 species as endangered, 15 species as near threatened, and 39 species as vulnerable, suggesting that nearly half of all flying fox species face significant threats to population viability. /=\

In Australia, flying foxes have been shot, poisoned, electrocuted and burned with flame throwers. Burning tires have have been set up below their camps and helicopters, land movers and chains saws have been revved up to produce noise to get rid of them. Some farmers have nets that cover acres of trees. There was even some discussion of introducing typhoid to exterminate them.

Birds of prey and carnivorous mammals, as well as snakes and large lizards may prey on flying foxes. Flying foxes tend to have fewer predators on islands. However, there have been several cases of introductions of non-native, arboreal snakes which have decimated flying fox populations. /=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, CNN, BBC, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2025