HORSESHOE BATS

Horseshoe bats are bats in the family Rhinolophidae, which is divided into six subgenera and many species groups. They are found in the Old World, mostly in tropical or subtropical areas, including Africa, Asia, Europe, and Oceania. The most recent common ancestor of all horseshoe bats lived 34–40 million years ago. [Source: Wikipedia]

Horseshoe bats get their common name from their large nose-leafs, which are shaped like horseshoes. The nose-leafs aid in echolocation. Horseshoe bats have highly sophisticated echolocation in which they use numerous, constant frequency calls to detect prey. They hunt insects and spiders by swooping down on prey from a perch, or snatching them off foliage. They typically live six or seven years; one greater horseshoe bat lived more than thirty years.

Horseshoe bats have been a source of human disease, food, and traditional medicine. Several species are the natural reservoirs of various SARS-related coronaviruses, and data strongly suggests they were the source of the SARS outbreak — which infected 8,000 people and killed 774 people in 2003, infecting more than — via an intermediate host, a masked palm civets. They also may have been the original source of the Covid-19 epidemic of the early 2000s. They are hunted for food in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Some species or their guano are used in traditional medicine in Nepal, India, Vietnam, and Senegal.

BATS, CHARACTERISTICS, FLIGHT, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ;

BAT SENSES AND ECHOLOCATION factsanddetails.com

BATS AND HUMANS: GOOD THINGS, DISEASE, RABIES AND DEATHS factsanddetails.com

KINDS OF BATS: SMALLEST, BIGGEST, VAMPIRE BATS factsanddetails.com

ASIAN FALSE VAMPIRE BATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BUMBLEBEE BATS (WORLD'S SMALLEST MAMMALS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

FLYING FOXES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WORLD’S BIGGEST BATS — LARGE, INDIAN AND GREAT FLYING FOXES — AND THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

FLYING FOXES OF THE ISLANDS OF INDONESIA AND THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Horseshoe Bat Characteristics

Horseshoe bats are considered small or medium-sized microbats, weighing 4 to 28 grams (0.14–0.99 ounces), with forearm lengths of three to 7.7 centimeters (1.2–3.0 inches) and combined lengths of head and body of 3.5 to centimeters (1.4–4.3 inches). One of the smaller species, the lesser horseshoe bat (R. hipposideros), weighs 4–10 grams (0.14–0.35 ounce), while one of the larger species, the greater horseshoe bat (R. ferrumequinum), weighs 16.5–28 grams (0.58–0.99 ounces). [Source: Wikipedia]

The fur of horseshoe bats is long and smooth in most species and varies from reddish-brown, to blackish, or bright orange-red. Their ears are large and leaf-shaped, nearly as wide as they are long, and conspicuously lack tragi (a prominence on the inner side of the external ear). Their eyes are very small. The skull has a bony protrusion on the snout called rostral inflation. Like most bats, horseshoe bats have two mammary glands on their chests. Adult females additionally have two teat-like projections on their abdomens, called pubic nipples or false nipples, which are not connected to mammary glands.

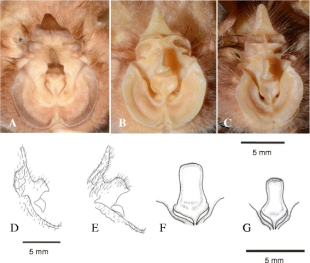

All horseshoe bats have large, leaf-like protuberances on their noses, which are called nose-leafs. The nose-leafs are important in species identification, and are composed of several parts. The pointed tip arising between the eyes is labeled the lancet; the u-shaped bottom of the nose-leaf is called the horseshoe; the knob projecting outwards from the center of the nose-leaf is the sella. The horseshoe is above the upper lip and is thin and flat. The lancet is triangular, pointed, and pocketed, and points up between the bats' eyes. The sella is flat and ridge-like and rises from behind the nostrils and points out perpendicular from the head.

Horseshoe Bat Echolocation

Horseshoe bats have very small eyes and vision is blocked by their large nose-leafs; thus it is assumed that vision is not a very important sense. Instead, they use echolocation (emitting sound waves and sensing their reflections to determine the location of objects) to navigate and this is arguably their most important sense. Horseshoe bats have some of the most sophisticated echolocation of any bat group and produce sound through their nostrils. While some bats use frequency-modulated echolocation, horseshoe bats use constant-frequency echolocation (also known as single-frequency echolocation). [Source: Wikipedia]

With Constant frequency (CF) echolocation bats emit sounds of almost constant frequency and use it to detect the velocity and movement of their prey. How it works: 1) As the bat moves towards a target, the echoes of its calls are Doppler shifted upward in frequency. 2) The bat compensates for this by changing the frequency of its calls, keeping the echoes in a narrow frequency range. This process is called Doppler shift compensation (DSC). 3) By keeping the echoes in this narrow range, the bat can quickly determine the target's distance, velocity, and other properties. [Source: Google AI]

Constant frequency (CF) echolocation is suited for open environments or for hunting while perched. Horseshoe bats have high duty cycles, meaning that when individuals are calling, they are producing sound more than 30 percent of the time. CF aids in distinguishing prey items based on size and is characteristic of bats that search for moving prey items in cluttered environments full of foliage. The frequencies used are high for bats. In some species, the nose-leafs likely assist in focusing the emission of sound, reducing the effect of environmental clutter. The nose-leaf in general acts like a parabolic reflector, aiming the produced sound while simultaneously shielding the ear from some of it.

Horseshoe bats have sophisticated senses of hearing due to their well-developed cochlea, and are able to detect Doppler-shifted echoes. This allows them to produce and receive sounds simultaneously. Within horseshoe bats, there is a negative relationship between ear length and echolocation frequency: Species with higher echolocation frequencies tend to have shorter ear lengths. During echolocation, the ears can move independently of each other in a "flickering" motion characteristic of the family, while the head simultaneously moves up and down or side to side.

Horseshoe Bat Feeding and Diet

Horseshoe bats either catch insects in flight or take insects and spiders from surfaces. They typically forage near the ground or near dense foliage, which allows them to detect non-flying prey. Horseshoe bats are capable of extremely maneuverable flight, including the ability to hover. Bats that are capable of hovering can exploit prey sources on surfaces, a resource most bat species cannot exploit. Species in this family may use regular, well-defined foraging areas. [Source: Matthew Wund and Phil Myers. Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The majority of horseshoe bats are nocturnal and hunt at night, At least one species, the greater horseshoe bat, has been observed catching prey in the tip of its wing by bending the phalanges around it, then transferring it to its mouth. Horseshoe bats that engage in perch feeding, roost on feeding perches and wait for prey to fly past, then fly out to capture it. Foraging usually occurs 5.0–5.9 meters (16.5–19.5 feet) above the ground. [Source: Wikipedia]

Horseshoe bats have especially small and rounded wingtips, low wing loading (large wings relative to body mass), and high camber (curvature). These factors give them increased agility and allow them to make quick, tight turns at slow speeds — an advantage in going after the kind of prey they go after.

Horseshoe Bat Behavior and Reproduction

Horseshoe bats are nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other), troglophilic (live in caves), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), and have daily torpor (a period of reduced activity, sometimes accompanied by a reduction in the metabolic rate, especially among animals with highmetabolic rates). [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

While some species are solitary, most horseshoe bats roost in colonies. They generally forage alone, and do not defend feeding territories but do tend to use well-defined foraging territories. Horseshoe bats have a roosting posture that is unique among bats. Instead of hanging with their wings folded at their sides, they wrap their wings and tail membranes around their bodies, enshrouding themselves. Because their hind limbs are poorly developed, they cannot scuttle on flat surfaces nor climb adeptly like other bats. [Source: Wikipedia]

Mehely's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus mehelyi)

The majority of species are moderately social. In some species, the sexes segregate annually when females form maternity colonies, though the sexes remain together all year in others. Individuals hunt solitarily. Horseshoe bats enter torpor to conserve energy. During torpor, their body temperature drops to as low as 16 °C (61 °F) and their metabolic rates slow. Torpor is employed by horseshoe bats in temperate, sub-tropical, and tropical regions. In temperate area, they do this for long periods of time and it becomes hibernation.

The mating systems of horseshoe bats are poorly understood. Most species are believed to be monogamous.Many horseshoe bat species have the adaptation of delayed fertilization in which there is a period of time between copulation and actual use of sperm to fertilize eggs. This is more common among temperate species than tropical ones. The gestation period is around seven weeks. Usually a single offspring is born, called a pup. Individuals reach sexual maturity by age two.

Did Horseshoe Bats Cause the Coronavirus Outbreak?

In May 2020, a few months after the Covid-19 outbreak began, an international team of scientists, including a prominent researcher at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, analyzed all known coronaviruses in Chinese bats and used genetic analysis to trace the likely origin of the novel coronavirus to horseshoe bats. James Gorman wrote in the New York Times: “In their report the scientists point to the great variety of these viruses in southern and southwestern China. The genetic evidence that the virus originated in bats was already overwhelming. Horseshoe bats, in particular, were considered likely hosts because other spillover diseases, like the SARS outbreak in 2003, came from viruses that originated in these bats, members of the genus Rhinolophus. [Source: James Gorman, New York Times, June 1, 2020]

“None of the bat viruses are close enough to the novel coronavirus to suggest that it jumped from bats to humans. The immediate progenitor of the new virus has not been found, and may have been present in bats or another animal. Pangolins were initially suspected, although more recent analysis of pangolin coronaviruses suggests that although they probably have played a part in the new virus’s evolution, there is no evidence that they were the immediate source.

“The new research includes an analysis of bat and viral evolution that strongly supports the suspected origin of the virus in horseshoe bats, but isn’t definitive, largely because a vast amount about such viruses remains unknown. Zheng-Li Shi, the director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases at the institute, known for work tracking down the source of the original SARS virus in bats and identifying SARS-CoV-2, as the novel coronavirus is known, is one of the authors of the new paper, along with Peter Daszak, the president of EcoHealth Alliance.

“The researchers collected oral and rectal swabs, as well as fecal pellets from bats in caves across China from 2010 to 2015, and used genetic sequencing to derive 781 partial sequences of the viruses. They compared these to sequence information already documented in computer databases on bat and pangolin coronaviruses. They found evidence that the novel coronavirus may have evolved in Yunnan Province, but could not rule out an origin elsewhere in Southeast Asia outside China.

Horseshoe Bat Species: 27) African Forest Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus silvestris); 28) Upland Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus hillorum); 29) Sakeji Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus sakejiensis); 30) Bokhara Horseshoe Bat(Rhinolophus bocharicus); 31) Greater Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum); 32) Geoffrey's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus clivosus); 33) Greater Japanese Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus nippon); 34) Horacek's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus horaceki); 35) Maclaud's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus maclaudi); 36) Ziama Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus ziama); 37) Hill's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus hilli); 38) Kahuzi Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus kahuzi); 39) Willard's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus willardi); 40) Ruwenzori Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus ruwenzorii); 41) Chinese Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus xinanzhongguoensis); 42) Big-eared Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus macrotis); 43) Osgood's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus osgoodi); 44) Allen's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus episcopus); 45) Thai Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus siamensis); 46, Schnitzler's Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus schnitzten); M) King Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus rex); 48) Marshall’s Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus marshalli))

“The family of bats that included the horseshoe genus, Rhinolophus, seems to have originated in China tens of millions of years ago. They have a long history of co-evolution with coronaviruses, which the report shows commonly jump from one bat species to another. Dr. Daszak said that the region where China, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar converge may be “the real hot spot for these viruses.” He said the region was characterized not only by bat and coronavirus diversity, but by urbanization, population growth and intense poultry and livestock farming, all of which could lead to viruses jumping from one species to another, and to the spread of human disease.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2025