BUDDHIST MONK LIFESTYLE

Tibetan monks Buddhist monks are often known in their own cultures by a word that means "sharer." A large portion of the Buddhist cannon consists of doctrines attributed to The Buddha on how monks are supposed to behave and what they were supposed to do. Traditionally monks have renounced all personal possession and sexual relations and relied on the charity of lay-people for necessities. Temples and monasteries are paid for with donations and fees paid to monks for performing funerals and other ceremonies.

In Buddhist societies, monks are generally respected by everyone and most families have a son who is monk or was a monk at one time. Monks are given free food and often allowed to ride free on buses and trains. Even the girlie bars and brothels on Patpong Road in Bangkok welcome saffron-robed monks who show up periodically recite mantras and make blessings to ensure good profits.

Few Buddhist monks are monks their entire lives. Those that are often become scholars, teachers, and healers. Some specialize in folk magic and even work as astrologers. Many spend much of their time presiding over funerals. Monks are free to a leave anytime they want. In Southeast Asia, many young men often serve a few weeks as a monk as a sort of coming of age rite, and then resume their ordinary lives. Undisciplined children are sometimes taken to monasteries by parents to set them straight.

The Theravada Buddhist scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi wrote: A “special aspect of the lifestyle of the Buddhist monk is that he lives in dependence on the offerings of others. He does not work for his living, he does not receive payment for his religious services, but he lives entirely in dependence on the support of the laity. Those who have confidence in the Dhamma provide him with the basic requisites, his robes, food, dwelling place, medicines, and whatever other simple material support he might need.” [Source: Virtual Library Sri Lanka lankalibrary.com ]

In Tibetan Buddhism and some other sects, some monks retreat to caves or remote huts to meditate and live as hermits. But generally most monks live in a community with other monks in a monastery. Theravada Buddhism devotes a great deal of literature to monks and their role in the monk community and society as a whole. In Mahayana Buddhism, there is more emphasis on pursing individual enlightenment.

See Buddha’s Begging Under BUDDHA’S LATER LIFE: TEACHING, DAILY ROUTINE, BEGGING AND MIRACLES: factsanddetails.com ; BUDDHIST MONKS AND NUNS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, SEX AND GREED factsanddetails.com ; SANGHA (BUDDHIST MONK COMMUNITIES) AND MONASTERIES factsanddetails.com ; MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; NOVICE MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM AND THEIR ORDINATION factsanddetails.com; FOREST MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES AND MONKS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN MONKS AND LAMAS factsanddetails.com; factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; Theravada Buddhism: Readings in Theravada Buddhism, Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org/ ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Pali Canon Online palicanon.org ; Vipassanā (Theravada Buddhist Meditation) Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Pali Canon - Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org ; Forest monk tradition abhayagiri.org/about/thai-forest-tradition ; BBC Theravada Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“What is the Sangha?: The Nature of Spiritual Community”

by Sangharakshita Amazon.com ;

“Teachings of a Buddhist Monk” by Ajahn Sumedho , Marcelle Hanselaar, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Three Japanese Buddhist Monks” (Penguin Great Ideas)

by Various and Meredith McKinney Amazon.com ;

“Adventures of the Mad Monk Ji Gong: The Drunken Wisdom of China's Famous Chan Buddhist Monk” by Guo Xiaoting, John Robert Shaw, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang” by Sally Hovey Wriggins Amazon.com;

“Xuanzang: China's Legendary Pilgrim and Translator”by Benjamin Brose Amazon.com;

“Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Faxian and James Legge Amazon.com;

“The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk”

by Georges B. J. Dreyfus Amazon.com;

“From a Mountain In Tibet: A Monk’s Journey” by Yeshe Losal Rinpoche Amazon.com;

“The Life of a Tibetan Monk” by Geshe Rabten Amazon.com;

:The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk” by Palden Gyatso Amazon.com;

“Himalayan Hermitess: The Life of a Tibetan Buddhist Nun” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer Amazon.com;

“Labrang Monastery: A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Borderlands, 1709-1958" by Paul Kocot Nietupski Amazon.com;

“Sera Monastery” by José Cabezón and Penpa Dorjee Amazon.com

Buddhist Monk Initiation

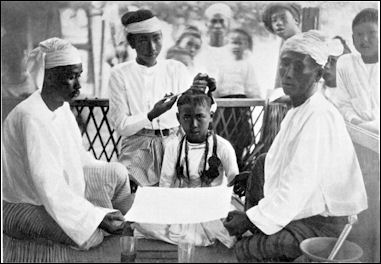

Cutting the hair To become a member of a Buddhist monastic order (sangha) involves two rites of passage: 1) Renunciation of the secular life; and 2) Acceptance of monasticism as a novice Because, in many cases, acceptance as a monk can not be made before the age of 20, the two rites can be separated by many years. Ordination is an important ceremony in all traditions, especially in Theravada Buddhism, where means becoming a monk. To become a Theravada monk, future novices are required to shave their head and face and don the yellow robes of the monk. Various vows are exchanged, including the repetition of the Ten Precepts. Then the the future novice is questioned about past behavior and their suitability for becomong a monk. If everything is order an officiating abbot admits the new novice monk. [Source: BBC ]

The vow taken by Theravada monks is essentially an embrace of the Three Jewels — Buddha, “Dharma” (Buddha's teachings), and the “Sangha” (the brother hood of monks) with the vow: "I take refuge in the Buddha, I take refuge in the law, I take refuge in the Community of monks." This is a ritual recitation of the intent to live as a Buddhist, to embody the dharma, and to seek guidance from the dharma, and, as such, it is a kind of minimal condition for becoming a Buddhist. For the monk, this simple ritual is the first step in a far more elaborate rite of passage: formal ordination into the sangha. The first step in this elaborate process is severing one's ties with domestic life, a ritual renunciation that is usually called "leaving home for homelessness." It is followed by a series of vows, particularly the vow to follow the code of monastic discipline, the Vinaya. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

The first five ascetics who became the first monks under The Buddha were joined by 55 others. They together with The Buddha are known as the 61 arhants. The were ordained by The Buddha by repeating the simple phrase: “Come monk; well-taught in the Dharma; fare the attainment of knowledge for making a complete anguish.” Others that came later were ordained after cutting their hair and beard, donning a robe and uttering three times: “I go to The Buddha for refuge, I go to Dharma for refuge, I go to the sangha for refuge.” This ritual remains the basis of the Theravada monk ordination process today.

Buddhist Monk Initiation Ceremony

In countries where Theravada Buddhism predominates, the novice monk initiation ceremony is an important rite of passage for young boys. Conducted when a boy is around 13 years year old, the event includes the offering of gifts to the Buddhist clergy at the temple where the ceremony is held, a feast hosted by the boys family, a formal head shaving ritual, and lots of prostrating by family members to the boy to symbolize the elevation to adulthood and the boy's new position as a son of Buddha. The parents gain merit by offering their son to Buddha and the grander the ceremony the more merit they earn. Elaborate ceremonies sometimes last several days and have musical performances, singing and chanting of poems that recall episodes of Buddha’s life.

While the boy’s head is being shaved, he is instructed by an abbot or senior monk to meditate on the action, contemplate its meaning and repeat thing like, "They are of this body, hair of the head, hairs of the body, nails, teeth and skin, which are unclean, abominable, filthy, lifeless and insubstantial." The hair of a novice monk is considered sacred. It is not allowed to touch the ground and is collected in a cloth spread out by the parents. After the head is shaved the boy turmeric and saffron powder is rubbed into the scalp and the newly anointed monk is given a robe and sent off to the monetary for several weeks or months. After that time he returns to a normal life.

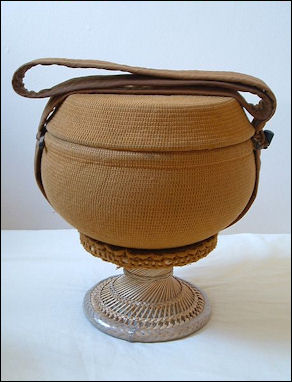

Upon ordinations a monks is given robes (often three robes, an inner, lower and outer ones), and simple possession such as a cup, bowl, razor, filter (for keeping out insects out their drinking water), an alms bowl and an umbrella. Monks and nuns in some Buddhist sects have five scars on their arm made with burning incense to remind them of the five basic moral prohibitions (the Panch Sila) which they vowed to avoid: killing, lying, stealing, adultery and drinking alcohol. After the marks are made the burns are cooled with watermelon rind.

The Buddha on What He Expected From Monks

The following sutra mentions Buddha's enlightenment and what he told his arhats (the first monks) on how to achieve (Sn 3.11 PTS: Sn 679-723 Nalaka Sutta: To Nalaka) :

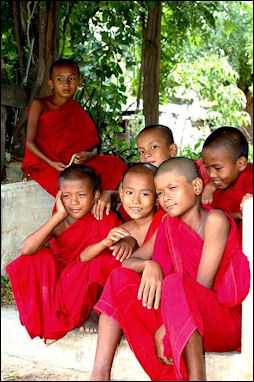

young monks in Myanmar

Abstaining from sexual intercourse,

abandoning various sensual pleasures,

be unopposed, unattached,

to beings moving & still.

'As I am, so are these. As are these, so am I.'

Drawing the parallel toyourself,

neither kill nor get others to kill.

Abandoning the wants & greed

where people run-of-the-mill are stuck,

practice with vision,cross over this hell.

Stomach not full,

moderate in food,

having few wants,

not being greedy,

always not hankering after desire:

one without hankering,is one who's unbound.

Instructed by the one

whose mind was set on his benefit,

Such, seeing in the future the utmost purity,

Nalaka, who had laid up a store of merit,

awaited the Victor expectantly, guarding his senses.

On hearing word of the Victor's turning of the foremost wheel,

he went, he saw, the bull among seers. Confident,

he asked the foremost sage

about the highest sagacity,

now that Asita's forecast

had come to pass.

Having gone on his almsround, the sage

should then go to the forest,

standing or taking a seat at the foot of a tree.

The enlightened one, intent on jhana,

should find delight in the forest,

should practice jhana at the foot of a tree,

attaining his own satisfaction.

Then, at the end of the night,

he should go to the village,

not delighting in an invitationor gift from the village.

Having gone to the village,

the sage should not carelessly

go among families.

Cutting off chatter,

he shouldn't utter a scheming word.

'I got something, that's fine.

I got nothing,that's good.'

Being such with regard to both,

he returns to the very same tree.

Wandering with his bowl in hand— not dumb,

but seemingly dumb —

he shouldn't despise a piddling gift

nor disparage the giver.

Buddhist Monk Code of Behavior

Begging monks in SE Asia

Monks follow the model of the Buddha who traded in his clothing for simple robes. They live as simply as possible and follow a strict code which includes refraining from stealing, drugs, alcohol, sex, entertainment, dancing, swearing, lying, sacrilegious acts, sex, and making money. The code includes the five basic commandments of Buddhism (the Panch Sila), plus three to five additional restrictions which may include prohibitions against things like eating after noon, sleeping on high beds and wearing jewelry or garlands.

Buddhist monks make a vow to give up all possessions. They are allowed to possess three robes and own a handful of personal items. Monks shave their heads and faces to discourage vanity and symbolize the renunciation of the worldly life. They also are supposed to eat only vegetarian food. The public supplies them with food and money for housing and medical care.

In Southeast Asia monks must follow 227 vows. In many places even touching a woman is taboo. Offenses can result in a reprimand, suspension or expulsion from the monastery. Many of the rules are similar to those followed by Hindus Sadhus (holy men).

Novice Buddhist Monks

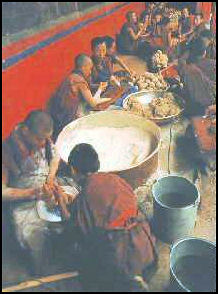

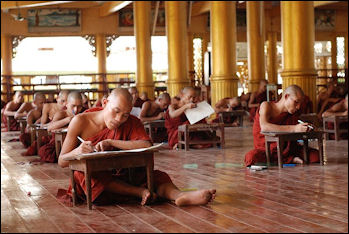

Most monks are novices. If all goes well they are ordained as full monks after two years or so. Novice monks study of the sacred texts in Pali and Sanskrit (the original Buddhist texts were written in these languages);engage in debates subtle points of Buddhist theology such as whether or not a rabbit has a horn and whether or not past and future events can be described as real. Young monks also have to perform chores around the monastery like collecting water and the sweeping floors. In their free time they often monkey around, or play cricket, soccer or baseball.

To earn merit on Buddha birthday some monks walk around and around their monasteries the entire day, carrying heavy wooden bound prayer books. Many classrooms in monastery colleges are outfit with buckets. If a monk can't remember a text he was supposed to recite he has to wear a bucket of water around his neck until he gets it right.

Buddhist Monk Duties

monk laborers in Tibet The life of a monk is not all quiet meditation, teaching, praying and studying. Monks preside over the important events in a person's life. They bless births, consecrate weddings, interpret the future, cure sickness and cremate the dead. A Buddhist's social life often revolves around festivals held at temples and monasteries.

Monks have traditionally taught reading and writing to young girls and boys, and morals, philosophy and meditation to older students. Today, they often teach poor children whose families can’t afford regular school. They also offer courses in architecture, sculpture, painting, carving, massage and brick-making. Some monks provide counseling for people with problems. Other specialize in healing, folk magic and fortune telling.

Monks also take part in public works projects and help villages build dams and irrigation projects, build schools and temples, preside over government events, bless dignitaries and projects, and preside over shop openings, new car purchases and moving into a house.

In some places, monks are called in to settle family and property disputes and offer advice and consul to people who are depressed, contemplating suicide or suffer from mental illness. They also reform juvenile delinquents and cure drugs addicts of their affliction. Buddhists can seek the moral and spiritual advice from a monk the same way Catholics seeks help from a priest. Many people also seek out monks for advice on matters usually associated with fortunetellers.

See Tough Love Buddhist Treatment for Addicts Under:ILLEGAL DRUGS, DRUG USERS, ADDICTS IN THAILAND factsanddetails.com

Clothes and Shaved Head of Buddhist Monks

Monks generally have shaved heads and are prohibited from wearing anything other than their robes, which consists of three garments: a bed sheet-size out garment, a similar-size inner garment and a loincloth-like underpants. Wearing clothing made from animal skin and leather is taboo. Monks are not even supposed to ride on animals.

The Theravada Buddhist scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi wrote: “The distinctive marks of the bhikkhu [monks] in all the Buddhist countries are the shaven head and the saffron robes. The reason the bhikkhu adopts this appearance is rooted in the very nature of his calling. The Buddhist monk seeks to realize the truth of anatta, of selflessness. This means the relinquishing of one’s claims to stand out as a special individual, to be a "somebody". The aim of the bhikkhu is to eliminate the sense of ego of self identification. Our clothes, hairstyle, and beard often become subtle ways by which we assert our sense of identity or express our self image. Bhikkhus give up their personal identity and blend into a larger body the Sangha. [Source: Virtual Library Sri Lanka lankalibrary.com ]

Robe of Buddhist Monks

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The symbolic significance of Buddhist robes can be easily seen in the common phrase for becoming a monk, "taking the robes." Although the color and style of robes varies considerably from country to country, as well as from school to school, all monastics wear robes. Not only does the robe physically mark the monk as distinct from the layperson, but it also serves as a physical reminder of the monk's ascetic lifestyle. The Buddha himself fashioned his own robe out of donated scraps and recommended that his followers do the same. Buddhist robes continue to be symbolically constructed in the same manner, sewn together out of many smaller pieces of cloth (although not usually actual scraps). [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

The robes worn by monks vary in color from place to place. Monks in Thailand and Cambodia wear yellow-orange or saffron robes; those in Tibet, Bhutan and Mongolia were maroon or wine-colored robes; monks in Korea wear grey; monks in China and Japan wear brown and yellow. Sometimes monks don black robes when they preside over a funeral or perform rites for the dead.

Monks sometimes meditate on their robes, chanting, "I wear these robes to avoid cold, to avoid heat, to prevent the bites of insects, mosquitos, snakes and bugs, to shelter from wind and sun, and to cover the shameful parts of my body." The robes can be positioned in a number of ways depending on the weather. Hoods, for example, are fashioned when the sun is really bright. Many go barefoot though most wear sandals.

Buddhist Monk's Daily Routine

Monk examinations in Bago Myanmar The daily routine of Buddhists monks varies from sect to sect, but the patterns are similar. Most monks wake up early, usually around 3:00am, live simply, do chores around the monastery and spend many hours meditating and praying. Monks sleep in dormitories, often on wooden beds with little or no privacy. Most of their duties and chores are performed in the main prayer hall. They generally eat before they meditate. Temple meals are vegetarian with natural spices such as pepper or powdered sesame.

Describing his experience at a Zen monastery journalist Patrick Smith wrote in National Geographic, "I ate an austere dinner of rice and fresh, cold vegetables. Under the watchful eye of a youthful priest-trainee, I spent 30 minutes at “zazen” meditation that evening. Before I could begin it took him that amount of time to get my position just right — legs properly crossed, hands correctly placed, head at the desired angle. Then I was to follow my thoughts wherever they led. I slept on a tatami mat on the floor."

The monasteries is most active after dawn or between 9:00am and 11:00am when chanting and prayers are being done. "At 3:30 the next morning," Smith wrote, "I was awakened and led to a room where row upon row of priests, kneeling on a vast spread of tatami, were softly chanting a Buddhist sutra. So the monastery began its day. It was cold and breakfast (as austere as dinner) was hours away; hunger gnawed at my attention, and my eyes wandered across the old plaster walls and the heavy ceiling beams, darkened by the smoke of countless sticks of incense...[Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic September 1994]

Buddhist Monks and Begging

In Theravada Buddhist societies in Southeast Asia, monks often spend the morning wandering from place to place in single file with a bowl, begging for food which they must consume before 12:00 noon. These monks are not allowed to eat anything for the rest of the day. Buddha himself wandered around with a begging bowl for a while and lived liked a monk.

The begging bowl is usually round, black and smooth and has a lid. An official of the Myanmar Religious Affairs Department told journalist Richard Ehrlich, "In the beginning of monastic history, monks picked up broken water jars discarded by housewives blackened them by baking them in a kitchen fire and converted them into alms bowls. But later on, Lord Buddha allowed the disciples to make new alms bowls."

During the morning begging ritual in Thailand, the monks walk through the streets with their begging bowls for 20 minutes or so. There is no talking, thanking, or eye contact. The monks accept the offerings, sometimes walking away silently, and sometimes bless the people who give them food. Male food givers often remove their sandals to show respect. Women are supposed to kneel. It is impolite to offer a banana with the tips still on.

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices:Vegetarianism is the ideal, certainly, but not always the practice, even in monasteries. Monks in particular are put in a kind of ethical double bind when it comes to eating. As much as they may wish to practice vegetarianism, in countries where monks go from home to home begging for their meals, they are also under an ethical and philosophical obligation to take (without grasping) whatever is offered; this provides the laity with the opportunity for a kind of domestic asceticism. Thus, if a layperson offers meat, the monk is obligated to accept it. The prohibition against killing or harming other beings, however, importantly involves intention, and if the monk had no say in the killing of the animal and if it was not killed specifically for him, then no karmic taint adheres to him because there was no ill intention on his part. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Buddhist Monks, Prayer, and Meditation

alms bowl Monks sit cross-legged in rows as they chant their prayers to the accompaniment of drums, bells and burning incense. Prayer and chanting sessions are usually held in private and lay people usually don't attend. These ceremonies are often held on a daily basis and sometimes they begin at three in the morning.

Meditating Zen monks cast their eyed downward, assume the lotus position, keep their backs straight and attempt to clear their mind so that "enlightenment will grow out of the state of nothingness." Novice monks who droop their head or fall asleep while mediating are whacked on the shoulder with a stick, by their instructors, who tell them to "Concentrate." [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic September 1994]

Monks spend a lot of time meditating. Meditation requires deep concentration and a lack of distraction. As a result, many Buddhists need to meditate somewhere quiet and private. Thus monasteries are often quiet and seem almost empty. They can also be quite noisy of teh monks are chanting while they are meditating or are debating.

Married Monks in Japan

Japanese Buddhist monks don’t have to be celibate. Both Buddhist and Shinto priests marry, and sons often inherit responsibility for their father's congregation when he dies. Wives sometimes receive some training and participate in the running of a temple.

Reporting from Yamagata prefecture in Japan, Chihiro Fukai wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Along with his job as the 33rd chief priest of the Toshoji temple of the Soto Buddhism sect in Nagai, Yamagata Prefecture, Takuya Ono takes care of his three children aged 12, 8 and 5 as a full-time househusband. “His wife, who works as a researcher in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture, lives separately from her family. [Source: Chihiro Fukai, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 16, 2014].

As Ono, 41, does all the housework, including cooking, he became well known as the “ikumen” chief priest from about a year ago. Ikumen is a recently coined Japanese word for fathers who actively take part in raising children. When he is invited as a lecturer to local meetings of parents and guardians or on other occasions, the priest of the temple established in the Muromachi period (1336-1573) talks about his feelings and the joy of raising children.

See Househusband Japanese Monk with Three Kids Under BUDDHIST MONKS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024